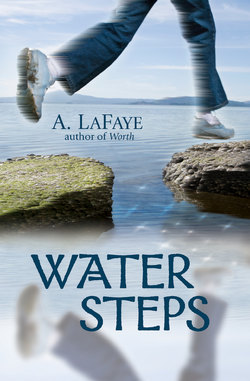

Читать книгу Water Steps - A. LaFaye - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWATER

Water scared me. Freaked me out so much I couldn’t walk through a rain puddle. My bones locked up. My muscles shrank. I turned to stone. The whole world went blue. Water scared me that much and Mem and Pep wanted me to live by a lake for the summer. A magic lake they said. Filled with silkies—the seal folk who take on human form when they leave the water. I didn’t care if the lake itself could fly!

I didn’t want to live on a lake. I didn’t want to live near a lake. I didn’t want to even see a picture of a lake.

Moving from the bed to kneel next to me, Pep said, “You don’t have to get in the lake, Kyna. You won’t even be able to see the water from the house. It sits high up on the shore. Nice and dry.”

“But I’ll know the water’s there, Pep. I’ll hear it,” I said, diving on the bed to roll up in my quilt.

Kissing me through the quilt, Mem said, “You can’t let your fears grow bigger than you, Kyna. They’ll swallow you up.”

My fear of water was as big as a lake. And I’d drown in it.

But I knew the rules. Face your fear one step at a time. Speaking through the quilt, I asked, “I don’t have to go in the water?”

“Not until you’re ready.” Mem rubbed my back.

Pep and Mem always said, “Not until you’re ready.”

They got this great slogan from Dr. Clark, the therapist they dragged me to every week. Worked just fine for me when it came to being ready to sleep over at a friend’s house or ride my bike downtown, but sometimes Mem and Pep thought I was ready before I really was. Last fall, they wanted me to take a shower. Not a slimy sponge bath in my nice dry bedroom on the third floor, but a shower in the tub that could fill up with water.

I refused and locked myself in my closet, yelling, “If you make me take a shower, I’ll never bathe again.”

Speaking through the door, Mem said, “Then you’ll smell so bad animals will roll on you for the scent.”

Our cat, Kippers, loved to roll on dirty socks and stick her head in my smelly shoes. I imagined myself walking outside, attracting every cat in the neighborhood. They’d rub all over me until I fell into the grass and disappeared under a pile of purring fur.

But the closet felt too small and dark. I had to open the door.

Pep gave me a hug and a kiss on the forehead.

“We’ll be right there with you, Kyna,” he said, already in his swim trunks—the green ones with the dancing sea horses. He has as many swimming trunks as he does pants. But he calls them togs.

“Can I bring my snorkle?” I held it up. Some kids have a security blanket. I have a breathing device for anything I have to do with water.

“No.” Mem shook her head. She wore the silver swimsuit that sparkled in the sun like the scales of a fish.

“But the tub could fill up with water.”

“The drain’s clear. I checked it just this evening,” Pep said, coming to my other side.

“It could clog up with hair and soap while we’re in there.”

“We won’t let it.” Mem gave me a big squeeze. “Come on, you’ll see.”

They led me into the hall.

I dragged my feet, shouting, “I’m not ready!”

“Yes, you are,” Mem said, as she swept my legs out from under me and carried me down the two flights of stairs to the bathroom. The room I hated most of all. The room I enjoyed having two full stories below me because it had water—everywhere. The sink. The toilet. The tub.

How did she know I was ready? Didn’t she hear me gasping for breath? Feel the cold sweat on my palms? The tight grip I had around her neck? As soon as she set me down and I felt the cool tiles under my feet, my body turned as stiff as those tiles.

Pep got in the shower. “I’ll show you.” I closed my eyes as he turned on the water. “Look at me, Kyna.”

I squeezed my eyes tight, so I didn’t have to see the water running over his face, near his mouth and nose, crowding up the spaces where breathing air is supposed to go.

Mem hugged me from behind and gave me a nudge with her knees. “Look, Kyna.”

Pep stood in the tub, the water washing over his shoulders, not his face. “See, just a little wetness. A little cool cleanness.” He rubbed the water over his skin.

“Let’s try it,” Mem said, stepping forward, bumping me ahead of her.

“Just my hand!” I screamed, putting it out.

“First your hand,” Mem said.

Shaking, I closed my eyes and put my hand forward, felt the tiny pat pat of the water. Rain. Rain leads to storms. Storms drown people at sea! I yanked my hand away and buried my face in Mem’s tummy. I’ll take hand sanitizer any day. Thank you very much.

“Try again, Kyna,” Pep said. “Just think of it as a little wash up in a very big sink.”

Sink? Huh! No one’s ever drowned in a sink.

Rubbing my back, Mem turned me around, then said, “Go on, both hands this time around. Then one foot. Little water steps.”

Water steps. We’d been taking water steps ever since we started visiting Dr. Clark. And sometimes, just sometimes, it made me wish they’d never adopted me.

Mem made me take my first water step when she put a tiny pool of water on the back of my hand and wouldn’t let me wipe it off. I was only three years old, but I felt sure it would spread and spread until it drowned me. But Mem did it again the next day, then the next and the next until I could look straight at that water touching my skin and not panic.

That spring, I had to put my whole hand in a bowl of water. When the water slipped over my skin, I felt sure it could pull me in. Had me gasping for breath in seconds. The leaves started to fall from the trees before I could do it without panting.

The summer before I started school, Mem began to put a glass of water on the table at every meal. Seeing that water just sitting in that glass still as you please set my stomach to sailing on rough seas. That first night, she set it on the far corner, then inched it closer to me each day. Bit by bit, the storm in my stomach lost its steam. When the glass got near enough for me to see the bubbles inside, I had to close my eyes, but I kept the sea calm in my stomach.

One month we worked on me holding the glass until I could stop shaking, then I had to put my lips on the rim. By the time pre-school started, I could take a sip of water without gagging.

In kindergarten, I graduated to wet wash cloth wipe downs. Now I can take a short shower if I keep the door open, but that’s not enough for Mem and Pep. They want me to take the next step and live on a lake for a summer. A whole summer. I’d never sleep. As soon as I close my eyes, I’d see myself drowning.

Drowning is my first memory.

Water choking me as it filled my nose and mouth, flooding my lungs. I kicked. I coughed. I spun, but I only sank deeper. My whole body aching, the world disappearing into darkness as I sank.

I remember smooth arms cradling me, the whooshing rush of water pressing against me as we sped to the surface, but the darkness took me before we broke into the night air. To this day, I ache to remember that first breath.

As Mem tells it, she and Pep hid in a cave on the seashore to wait out a terrible storm. The sea had grown angry while they swam by the shore. It whipped and churned like a sheet held in the hands of many frenzied children, snapping it up and down from all sides. The ships at sea were tossed like so many balls thrown on the sheet—my family’s boat among them.

The folks around town say my father had been a good seaman who even sailed the treacherous waters of Tierra del Fuego down on the tip of South America—a patch of sea so fierce it’d been sinking boats for hundreds, maybe even thousands of years. Seaman or no seaman, he couldn’t navigate that terrible storm off the coast of Maine. The sea had gone to war with the wind. Our boat got caught up in the battle. They tugged and pulled at the boat. The wind pushed it toward the shore. The sea bashed it into the rocks.

Mem and Pep stood in the cave, holding each other, praying the boat would survive. But it began to sink. Rushing down the rocks, Mem and Pep dove into the angry sea to rescue my family. They could only save me. The sea swallowed my whole family. My mother, who had wax white skin and red hair. My father, who had a gap in his mustache, right below his nose. My brother, Kenny, who wore a berry blue coat when he went to sea. And even my Grandma Bella, who wore a yellow rubber hat like the deep-sea fisherman you see on the package of fish sticks.

I hate fish sticks, but I love the box. It makes me think of Grandma Bella. I don’t remember her. I can’t. I was just a toddle-about baby when that boat sank. I only know my family from the pictures—all the pictures that Mem and Pep put in frames for me and spread throughout that narrow little house on Larpin Street in Perryville that’d belonged to Grandma Bella.

Mem and Pep did everything they could to keep me close to my family—fight for the house our family lived in with Grandma Bella, use all the furniture my family had lived with before the sea took them, and hang every last picture of my family they could find. My family was at sea in so many of those pictures, their faces wide with smiles, the sun forcing them to squint. They loved the sea. I hate it.

And no matter how many water steps Mem and Pep force me to take, I’ll still hate the sea. Now. Forever. And always. I won’t go live on a lake for the summer. I won’t.