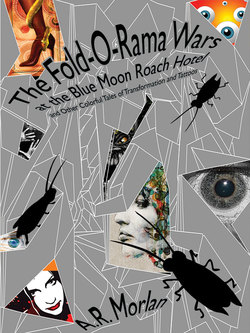

Читать книгу The Fold-O-Rama Wars at the Blue Moon Roach Hotel and Other Colorful Tales of Transformation and Tattoos - A. R. Morlan - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFROM THE WALLS OF IREZUMI

“So, why with the tattooing, all over you like that? What you do that for? That any way for a girl to look?”

Mr. Beniamino had asked her one time too many, and before Gwynn realized that she’d even answered him, she’d said in reply, “So why you want to stay canvas? All blank and vanilla? Nothing you wanted to say about yourself, on yourself?”

“I got nothing to say that I can’t say for myself. So, there on your arm, what’s that you’re sayin’? You say...what? That you got a line of little pictures running along your forearm? And none of them bigger than a sneeze? What’s that say, huh? Buncha little thoughts?”

Moving deliberately, while a feeling of biting down hard on a mouthful of dry, shifting hair passed through her body, Gwynn placed the breakfast tray on the short-legged bed table before Mr. Beniamino, and said evenly as she lifted one cover after another off the individual shallow bowls, “No, ‘bunch’ deliveries. Every flash-scrap I bring to the subtropolis, I get a new tattoo. Based on what flash-scrap I’ve brought down. ’Course, if it’s a full Irezumi, all I do is get one detail from it. From the back, that’s where all Irezumi designs grow from. But I don’t do it traditional-style. Electric all the way. None of that pounding the ink in—”

“You kids, you’re all sick. Full body tattoos, coloring in your faces, for what. I hear what them nurses call youse kids. Know what they call this here ward?”

She waited until he’d slid his spoon into a gelatinous mound of poached eggs, the rounded silvery bowl of the utensil cleaving the rancid yellow center like a surgical scalpel removing a cataract from an aged eye, before saying simply, “‘Pigment ghettoes.’ And ’this here ward’ isn’t the only p.g. to be had. But the way I figure it is, I’m one of the lucky ones. I get the privilege of witnessing my own inevitable physical deterioration first-hand. One sagging tattooed wrinkle at a time. ’Cept for you. You’re so...canvas.”

He’d slid the bowlful of soft egg into his dry-lipped mouth, and swallowed with a phlegmy gurgle, before saying to her, his watery eyes trained, unblinking, on her pigment flushed face, “I ain’t ‘canvas’...you think I don’t know your lingo. There ain’t a lot of me, but it ain’t all canvas—”

* * * *

The bus seemed to float above the highway for a second, as it descended from the latest hilly section. To Gwynn’s left, just through the grimy window, she saw yet another yellow and black sign warning motorists to be aware of hunters in the surrounding wooded hillsides. Do they dart onto the highway, like deer? Or do they just shoot cars and busses?

She’d been riding this bus for too long; the constant rocking motion of the seat as it compensated for each rise and dip in the road was starting to give her a headache. Under the dark folds of her abaya, she pressed her foil-wrapped flash-scrap against her bare midriff. A learned response to fatigue or a break in her concentration; while it wasn’t exactly illegal to transport medically harvested flash-scrap, there were a lot of people who didn’t want to see it, and never mind know about it.

Three seats ahead of her, a couple of real Muslim ladies were seated side by side, neither of them looking out the side windows, their black-draped heads unmoving as the bus continued to roll further and further from Pittsburg, moving deeper and deeper into the hills of yellow ocher, vermillion and bronze-orange clustered trees.

No chance of the driver seeing a blaze-orange-suited hunter before he shot out the tires, she found herself thinking; when she was tired, her mind tended to fuzz off, go random and surreal. The way it did whenever she’d get a tattoo. Concentrate on nothing, just let anything filter up, as long as thoughts of pain were repelled. Scratching her right forearm beneath the shielding yards of black fabric, while staring at the draped heads of the Muslim women ahead of her, Gwynn was briefly grateful for the large Muslim enclaves common to virtually every city across America—she could avoid the stares and barely-whispered comments from all the canvas who found her markings offensive, and, albeit fleetingly, physically lose herself in a different human tribe, merely by donning that heavy tent of black cotton. Looking at the canvas walking past her on the street wasn’t as...vanilla when she had to look at them through the abaya’s screen-like eye-hole mesh.

This time of the year was the best time to wear the abaya, Gwynn realized—while the autumn sun was bright, bottled-water clear, it was also weak, the rays barely penetrating the confines of her robe. Ironic, how summer—the time her tattoos alone most needed protection—was also the worst time to wear the thing. Black cotton absorbed the sunlight; how the real Muslim women could stand it was beyond Gwynn’s ability to comprehend such a problem. Although it sort of gave her insight into some of the taunts passing canvas spat out at her—“Why don’tcha just dunk your head in a paint-can?”—“If you don’t watch out, your face will stay that way”—“Masochist bimbo!”—“Freak-face!”—semi-articulate screes which only hid the speaker’s fear and awe, allowed them to hide behind jibes, rather than simply ask about her tattoos.

Sliding her free hand along her torso and neck under the abaya, hoping that her movement wasn’t visible through the fabric, Gwynn stroked her right cheek, the one with the ombré flow of deepest azure down to water-color-delicate sunrise-sky-blue. Her “plain” cheek, compared to the Celtic knots which adorned her chin, left cheek and part of her forehead.

This side of my face is for my father’s people...somewhere back ages ago, my great-great-to-I-don’t-know-what-power grandfather fought with William Wallace. The guy Mel Gibson plated in that movie decades ago, she imagined herself saying to any canvas brave enough to actually ask her why she’d done what she did to her face. They painted themselves blue to scare their enemies. For strength. For unity. The other half of my face, that’s for my mother’s people. For the Irish. Them and the Scots, they were both screwed over by the British. Tried to take away their right to dance, to play bagpipes, to speak their languages. I say, let them try to take this off of me. Let them try. My face sings. My face dances. It speaks.

Another sudden rise, followed by the corresponding elevator-like decent. The abayas of the two women ahead of her puffed up around them, then settled down in predetermined folds on their shoulders.

Gwynn felt as if the trees flanking the road were spreading, ready to engulf the bus as it moved northeast of the city they’d left behind over half an hour ago. One of the guys who’d done some of the work on her back, the huge Celtic cross whose base rested just above the cleft in her behind, used to say basically the same thing about tattoos.

“I think they spread, y’know, under the epidermis. Color goes migrating away from the lines, meets up with the colors from the other side, and next thing you know, you got less canvas. Just does it in places you can’t look at too easy. So’s you can’t stop it.”

She’d wondered if the bees-trapped-in-a-jar drone of the tattoo needle had begun to shake the guy’s brain cells loose. Too much repetitive motion—hold the needle, let it secrete color under the flesh, wipe away the excess ink and blood with the other hand, then do it over again.

But now, as she rode, nearly motionless, on the rising and falling bus, the press of trees surrounding the highway did resemble loose pigment migrating under unsuspecting unpigmented canvas. Overhanging branches thick with freshly-ground-bright pigment spread closer and closer to the highway’s shoulders, as if seeking that thin tire-stained ribbon of flat chrome yellow in the center of the road. Pigment calling to pigment.

Definitely like the way tattooed people sought each other out, not merely for company, but for empathy. In remembrance of that shared bond of temporary pain, as the canvas became artwork; partly for the fellowship, perhaps more so for the individuality within the flesh-tribe.

Those women up front, swaying slightly under their abayas as the bus rounded a slight curve in the highway, their tribe depended more on adherence, on uniformity, of sameness of purpose and faith. The more you looked like your brethren, the closer you’d come to your life’s goal. Everyone pray at the same time, while facing the same direction. All women smothered in black robes, or head-wrapped in a hijab. The men, mostly bearded. Not all that different, really, than the Amish and the Mennonites originally more common to the state.

When she was younger, Gwynn would ask the women in the Amish and Mennonite communities why they wore those filmy white hats on their bunned hair. The answer was usually the same, a reference to Corinthians, about women covering their heads in prayer. But for some reason, none of them ever asked Gwynn about her facial art. As if they didn’t want to know, or simply wanted to forget they’d seen her.

Once, during a flash-scrap run she’d taken to the Records Center of Kansas City (the previous wearer of the flash-scrap she was carrying had specifically willed his body art to that city, why she’d had no earthly idea), the place where all the original episodes of M*A*S*H and some show she’d never heard of before called Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea were stored—as the travel brochure for the city had proudly noted—she’d been sharing her bus seat with a Muslim woman, who wore the more common hijab rather than an abaya. Gwynn wasn’t wearing much more than a tee shirt with holes cut out over her best bits of tattooing and a pair of shorts—it was early August, and almost too hot to wear her skin. For a second, she’d felt ashamed of herself; she knew her seatmate instinctively frowned not only on the skimpy clothes, but on the tattoos. But the woman was actually nice about it.

“Those must have been rather painful,” was all she’d said, and politely at that, as she tacitly pointed at Gwynn’s face.

“Not too bad...not worse than the rest of my body. It doesn’t last, though—”

“So these are temporary, like henna ones?”

“Oh no, no...they’re on for good. Really, I should wear more clothing, ’cause the sun can fade these, but sun-block works, too.”

“And it is cooler,” the woman had smiled, before noticing the small cooler perched on Gwynn’s knees. “At least your knees are cool—”

The flash-scrap was inside the cooler, loosely folded, packed in sterile ice and protected with some sort of surgical gauze the person who’d removed it from the donor had layered between the folds. She didn’t know if a doctor had done it, or one of those nurses trained to extract donor eyes for cornea transplants. Some of them had learned to diversify, once flash-scrap donations became the norm. But Gwynn couldn’t bring herself to tell this stranger about the contents of the cooler, even as she feared that the woman might think something edible was inside, and hope that Gwynn might offer her whatever it was—

“Yeah, real cool. Glacial. Is this the first time you’ve been to Kansas City?”

Gwynn couldn’t really recall what the woman had said to her after that; she did remember being grateful that the hijab-swathed stranger hadn’t lectured her on her tattoos, or her lack of clothing.

She hadn’t seen the woman again once they got off the bus, and Gwynn made her way to the Record Center, but in ways, she wished that the woman had been headed that way, too. Having her for a traveling companion would have been good. Gwynn could have told herself that the canvas was making remarks about the woman, instead of her.

On the road an hour now, half an hour to go before they reached the Iron Mountain National Underground Storage facility. Where the guards stood before those steel gates, ready to request that all visitors surrender their weapons, drugs and explosives, despite the inherent inanity of their assumption that anyone bearing such items would first admit that they had them on his or her person in the first place. As if carrying a gun, a needle and a stick of dynamite was so commonplace as toting a pocket comb, a pager and a half-empty box of breath mints.

There was a rectangle of hot flesh on her midriff—the flash-scrap stored in that folded-over square of heavy-duty cooking foil was pressing uncomfortably into her skin. Gwynn imagined how her flesh must look—all alligator-wrinkled over one of her favorite tattoos, the blackwork dragon with the pearl in its mouth. The one that could be easily seen through her uniform—

* * * *

“What that you got there, on your belly?” Mr. Beniamino pointed one knobbed finger at Gwynn’s midsection as she bent over him, prior to rolling him over onto one side of the bed. At a hundred-plus years, the old man barely weighed more than a laundry sack filled with soiled sheets, but his mind was dismayingly sharp. Always with the questions—

“A dragon. Blackwork...no shading, all black ink. And yes, it was very painful,” she went on, anticipating his inevitable next question.

Aside from his advanced age, Mr. Beniamino had so little in common with the rest of the people in the nursing home; not only was he canvas, from the liver-spotted top of his balding head to his oddly shiny thick-nailed toes, but he even lacked the basics of pierced ears. Gwynn’s grandparents had told her that one of the correspondents on the first real newsmagazine, 60 Minutes, had worn an earring. And that was long before full body tattoos and multiple piercings were relatively common among the generation just reaching adulthood. Every day, as she worked her regular job among the remains of that embellished generation, washing and feeding those once proudly adorned bodies, Gwynn felt the inner pangs of helplessness at having been born a generation too late. Growing up, she’d seen people with head-to-toe patterns walking unattacked and uninsulted down the street, the sunlight glinting off their facial piercings, their body jewelry making soft metallic clacking noises as they walked. That generation had role models like the British Leopard Man, or The Enigma—that blue-jigsaw-puzzle-covered man. The one who ate live crickets on that old show The X-Files. Plus they respected the original masters of Irezumi, the ancient Japanese art of whole-body tattooing, done the old way, with pounded needles wielded by hand. But her parents and their whole generation should have heeded the origins of Irezumi...how those people who were not part of the aristocracy were forbidden to wear patterned kimono, so they created body kimono, of the most fantastic and intricate patterns, ones which could be hidden under clothing of the plainest sort. Eventually, mainly criminals sported Irezumi...just as Gwynn and those of her new tribe were considered to be flesh felons, the non-conformists, the throwbacks to that hedonistic, gaudy, decorated generation whose children mostly rebelled against their parents’ excesses of the epidermis. Gwynn supposed that the rise of the Muslim faith in the United States might have had something to do with it; once they surpassed the Southern Baptists as the most common faith in the country, a certain mindset began to permeate the country, even if the actual tenets of that faith didn’t.

Which is such a shame, Gwynn decided. Aside from the mutawa in the most fundamentalist neighborhoods in the largest cities, the whole religious police concept simply wasn’t a part of the American Muslim majority. They may not like how we look, but they don’t attack us out loud. Or if they ask a question, it’s not a pointless one—

“If it’s so painful, why you do it?” Gwyn let her patient roll himself back onto the changed side of the bed, before tackling the corners of the fresh sheet on the other side.

“‘Why’? Because I want to. Because I know they drive you crazy.”

“You’re the crazy...without them, would you be here? Changing shitpans? Spooning gelatin past toothless gums?” He flopped backside first onto his fresh sheet, sending up a stale scent of dry skin, old p.j.’s and age Gwynn’s way.

“I’d be changing bedpans somewhere, if not here. I am a nursing assistant. Diploma and everything.”

“That diploma, it tattooed somewhere on your body, too? You gots everything else all over you—”

“On my behind, Mr. B. right on my cheeks. Wanna see?”

‘Smart mouth...stuck in the ghetto, is what you are. Put yourself there...if someone was to make you get them tattoos, then you wouldn’t like them so much. People’ll put up with stupid, crazy stuff, long as they do it to themselves. But made to do it is a whole lot of different. I knows. Been there myself. Whole lot of different.”

That Mr. Beniamino had been right about her more or less being forced to work in a nursing home rather than a regular hospital pained Gwynn so much she’d barely listened to much else he’d said that afternoon; she hadn’t intended to mire herself in such a depressing job. Patients who inevitably died, taking their personal flash, those designs forever marked “SOLD” on their respective tattoo artist’s walls, with them. Patients who would never get better, and actually leave this place once they were brought here. Patients who ultimately reminded Gwynn of her own inevitable mortality day after day...including the time when her own flash would be consigned either to the grave, or to the crematorium’s flames.

Which is why she’d become a flash-scrap courier; one of her patients had stipulated in her will that the full-back tattoo she’d gotten decades earlier was to be surgically removed like a patch of leather, then transported to an underground storage unit in the Iron Mountain area. The only problem was, the will had been executed long before the woman herself passed on, and the person designated to transport the flash-scrap had also died. But the storage fee had been paid for in advance, much like a pre-arranged burial, so the only problem was how to get the preserved tattoo from here to there. Flash-scrap has to be carried by hand, and transported on the ground. Airplanes are out; drug-sniffing dogs and pigs inevitably nosed out flash, and went berserk. Worse than someone trying to smuggle in meat from overseas. Flash-scrap wasn’t exactly illegal, but it was deemed unsavory, and undesirable in Muslim enclaves. So...you either had to drive it, or ride with it, on the ground. Usually busses were used, why Gwynn didn’t know. It was just something the other couriers did.

People like Roano from New Mexico, or Moreen Pinchos from Florida, the one who specialized in flash from Latino gang members, or that crazy Calvino Burrell, the guy who went from state penitentiaries to death rows, collecting flash from prisoners who had the time and patience to do the most fantastic blackwork on their bodies, as well as the bodies of their fellow prisoners. She and Moreen and Calvino had once found themselves on the same bus headed for Iron Mountain, each toting a red-and-white cooler of harvested flash. Some of their fellow passengers knew what they were carrying, and every time the bus stopped, they’d move around, playing musical bus seats, until the three of them were sitting in the middle of a ring of empty seats. So they’d actually had to talk to each other.

Which was the funny thing about scrap couriers; while they were all more or less part of the flesh tribe of extreme tattoo collectors, and all had the pigment ghetto job situation facing them at other times, none of them actually liked each other.

Moreen hated Roano for his facial piercings and turquoise lip plug (which she openly considered “primitive”); Roano despised that Indian courier, the one who dubbed himself Qochata because the name meant “white man” and Qochata was a full-blooded Hopi which Roano felt was some sort of ethnic slap in somebody’s face; Qochata thought Calvino was a nut job because Calvino had had his entire head tattooed, then let his hair grow back over it, just so he’d have “something to look forward to once my hair starts to fall out” and Calvino didn’t like Gwynn, because she insisted on wearing an abaya during most of her trips to the subtropolises...while Gwynn thought Moreen was pretentious for restricting all of her blackwork tattoos (a necessity on her dark brown skin) to what most canvas considered “safe” areas...her back, her upper arms, and her thighs, places easy to cover with clothes, to please canvas job service personnel.

On this trip, taken down this same highway, in what may have been the same damned tour bus, but definitely with a different driver, only six or so months earlier, Gwynn’s seatmate was Moreen, whom she disliked less than Calvino, who—once he noticed the overt migration of their fellow travelers to seats south and north of theirs—began rubbing their mission into the other people’s faces.

“Girls, what kind of flash you got in there? Mine’s primo—filet of serial killer. Man spent twelve years there on appeal...guy in the next cell over tattooed him through the bars, all over his lower arms. Never saw the face of the artist, but damn if he didn’t do fine work.”

“I’m sure there’s some squirrel sitting in a tree miles away that didn’t hear you,” Moreen had sniffed, as she crossed her legs under the small cooler perched on her lap.

“I ain’t loud...I’m proud. You want I should show you this flash? Once it goes underground, ain’t nobody gonna see it...it’s gonna be outasight, like all them archive pictures Bill Gates bought and hid down there—”

“If you’re referring to the Bettmann Archives, at least they’re safe in that vault. They won’t degrade, or be subject to mishandling. You did realize, didn’t you, that people had been scribbling on them, bending the corners, letting them fade—”

“This here flash, it didn’t get no chance to fade where this guy was...’course you don’t have to worry about yours fading, do you, Mo-Mo?”

“Black people can get sunburned, too. It just takes a longer exposure,” she’d sniffed, before uncrossing her legs and sitting with both feet flat on the floor of the bus.

“Rosa Parks is pissed...how ’bout you, Tent-Girl? You gonna roast under that thing? Broil off your tattoos?”

Under her breath, Moreen whispered “Ignore the putz” but Gwynn was used to hearing far worse from canvas on the street, so she set her cooler on the floor, and lifted up her abaya with both hands, revealing her blue-and-black covered face, and fully-inked body, covered only by a sleeveless tube dress. She could hear the hissing exhalations behind and ahead of her, as the other passengers got a first look at her, but they were only canvas. Not worth her discomfort.

“I don’t know, Calvino...do they look done to you yet?”

Calvino may have had his scalp tattooed but he was still a jinny (a skin virgin, in canvas-speak) when it came to facial tattoos.

Gwynn thought it was the blue side of her face that spooked him into a few minutes of silence, but like the British who kept on attacking the rebel Scotsmen centuries ago, Calvino soon re-armed himself and started in again. Humming softly at first, he soon broke into full-voice song, to the tune of “The Halls of Montezuma”:

“From the walls of Irezumi/to the shelves of pickled knees—”

Moreen leaned close to Gwynn, and said succinctly, her voice ringing in Gwynn’s ear, “If you ask me, that man’s momma watched too much Tom Green while she was carrying him,” pronouncing the work “ask” like “ax,” as some black people were wont to do.

Gwynn had digested her words for the next mile or so, then had to ask—even though she did find Moreen to be too self-righteous for words—if Tom Green was the one who played Bevis or Butthead on that Jackass show on MTV. She vaguely remembered her parents talking about all the strange things they used to show on that channel, but after a while all the weirdness tended to merge together. Maybe this Green person was part of The Real World?

Moreen had to think about it for another couple of miles, before saying, “I’m not sure...I just know he married one of Charlie’s Angels. Don’t ask me if she was one of the TV ones, or from the movie. Been too much going on in entertainment for me to keep up with it.”

And that had been all Moreen had had to say for the rest of the trip. Calvino’s song had more verses, all of them increasingly disgusting and deranged, but only the first two lines stuck in Gwynn’s brain.

From the walls of—

If she didn’t think—consciously—of something, anything, else, she’d wind up singing the damned song out loud, and freak everyone out, the way Calvino had done back in May, when the other bus driver stopped the bus five miles from the converted limestone mine, and told Calvino to hoof it.

She and Moreen had both crawled into separate seats, so they could wave buh-bye to him as the bus lurched away down the highway....

* * * *

“—but it ain’t all canvas...‘canvas.’ What kind of a name is that, for a human being? What’s with this name bit? Huh?” Mr. B. grabbed her forearm with a sticks-and-knobs talon-like hand, all the while continuing to spoon up quivering blobs of poached egg, shoving them greedily into his mouth between words.

Trying to shake his hand loose, Gwynn said, “It’s an extension of the whole body art notion...the human body as canvas, waiting to be filled with art. You do realize that some people can’t stand the sight of an unadorned body. It’s like a waste of potential. It’s like...just putting up with the way you were born, without trying to do something about it. Like never cutting your hair or fingernails, just because you’re born that way. It’s ignoring your potential. So...we call people without tattoos ‘canvas.’ Like the way...like, how initiated people have names for non-initiates.”

“Oh...like black people calling us ‘honky’ or ‘cracker’? Or us calling them—”

“Now, people have moved past those words. Anyone, any color, can be canvas. It’s not a race, it’s a decision.”

He’d let go of her arm, then, and slurped up the rest of his eggs, before adding, just as she was getting ready to quit his room, “So what this is, is a decision. Answer me this, girlie—”

“My name is Gwynn...Ms. Gannon if you prefer—”

“Girlie-Gwynn-Gannon, you answer me this...whose decision?”

She was about to answer when she thought about it a bit more; while most tattoo artists did follow a customer’s request when it came to flash, some did specialize in carting designs directly on the skin, with no pre-inked outlines rubbed on the skin first, no guidelines at all save their own imagination, and their instinct as to what would look best on that particular person—

“Usually the person getting the tattoo done. In most cases. And even if the artist does do the deciding, the person getting it has to choose to have one done in the first place—”

“So you people, you choose?” He’d moved on to his limp butter-substitute-slathered toast, but those moist, glassy eyes were still aimed in her direction.

“Of course we choose to have this done—”

“Your choice, your decision?”

It didn’t seem like it should be a question—

“Of course...tattoo artists don’t roam the streets, grabbing jinny canvas at random—”

“‘Jinny’?”

“Novices. Never-been-touched by the needle—”

“More names...you were saying?”

“They don’t do guerilla tattoos...what’s the sense in that? Why do it to someone who doesn’t want it?”

* * * *

Only fifteen minutes or so until she reached the archives. Around her, the other passengers began stirring, looking in purses, checking tickets, gathering up carry-ons in knapsacks or paper shopping bags.

The bus wouldn’t bring Gwynn directly to the gates, of course; she’d have to hire a cab to take her there. Not an unexpected expense, but this time around, this whole trip was on her dollar. The fee for depositing the flash-scrap was coming out of her credit card. It hadn’t been paid in advance—just as the small rectangle of flash hadn’t been harvested in the usual way. Hence, the foil shroud, and the need for her to wear the abaya...rather than the choice to wear it.

Wishing she’d invested in her own cooler, Gwynn checked to make sure that the two vertical bands of duct tape she’d used to secure the flash-scrap to her midriff were still sticking to her bare skin. It wouldn’t do for the foil packet to fall off as she walked to the steel gates, and talked to the guards standing there. They might think it a thin slab of explosives, possibly destroy it. Which would never, never do. Not with this flash-scrap.

* * * *

“‘Why do it to someone who doesn’t want it?’” Mr. Beniamino’s voice was a parchment counterpoint to her own, and she’d stood in the doorway, wanting desperately to leave this flesh fossil and go on to one of her own tribe members, the decorated, perhaps decadent elders who didn’t yammer the same questions about her tattoos, but yet...something in the tone of his voice, the phrasing of her own words, made her want to know what point he was obviously trying to make.

“You get the Internet? Use that mousie thing, go browsing?”

“Who doesn’t?”

“‘Who—’ Oh, you make me sad, so sad, Gwynn-girlie. Okay, you got your mouse. And your Internet. Where, I am told, because I am not on it, that you can find anything, about everything. Right?”

“Yes.”

“So, you ask, for information about a thing, and it will give it to you?” he asked around his soggy toast.

“If you use a search engine...and if the information you’re looking for is in the databases—”

“It is, it is...so, you do me a favor. Do you a favor. Start up that engine thing of yours, and ask it something. This engine, it has like an index? A Yellow Pages for what it does and doesn’t have?”

“Yes—” She was vaguely aware that she’d have to go to the bathroom soon, and shifted her legs accordingly.

“Good. Then, you ask it about this—”

* * * *

The cab driver treated her as if she was actually a Muslim woman, which was fine with Gwynn; she did have to consciously remember to pay him with her right hand, since she had a small tattoo on her left ring finger (a sun-faded memory of a long-ago boyfriend), but once he reached the gleaming steel gates fronting the storage facility, he did ask, “You a researcher, Ma’am?”

A beat, then, “Yes, I am. How much do I owe you, sir?”

Her abaya may have been something of a lie, but she didn’t feel guilty about saying she was a researcher. She’d copied down the words Mr. Beniamino had told her, words which sounded somewhat familiar, but which belonged to a distant past, close to a century ago. When he was only twenty-some months old, and said he, too, inhabited a ghetto...albeit of a different sort than the discrimination-by-design one she and her flesh-tribe members inhabited during working hours.

Using the words he’d provided, then adding some cross-references of her own, she’d spent an entire weekend before her monitor, her mouse slick-skinned from the sweat of her fingers as she’d navigated the Internet, taking a journey into a past where tattoos had a far different meaning—

The researcher line worked with the cabbie; as far as the guards were concerned, her black robes equaled seriousness of purpose, so she was waved through.

Despite all the times she’d taken flash-scraps to the climate-controlled vault here, that elevator ride down two hundred and twenty feet to the subtropolis below never failed to sicken her. Protectively, she wrapped her arms over her midriff, pressing the foil packet even deeper into her skin. Close to two hours of this, and she might be marked there for life.

Thinking of Mr. Beniamino, the phrase “marked for life” took on new shades of meaning; as the elevator slid downward, letting her stomach adhere to her diaphragm, she wished that he’d still been alive when she’d come back to his room the Monday after he’d spoken to her. He had to have passed on either late Sunday night, or early that morning; his urinal was partly full, and unchanged. None of the night crew was good for squat, and some of them were canvas. So much for the superiority of unmarked workers.

In the moments before the utter finality of his death really impacted on her, Gwynn had slid his pj sleeves up his arms, all the way to the saggy-fleshed elbows, and examined his forearms, searching among the irregular liver spots and slightly raised moles for his tattoo. Since he’d been a toddler when he’d gotten it, barely more than a baby, it might have faded, or spread out as he’d grown—

—that it was blue didn’t help much; most of his submerged veins were also a watery blue.

But she knew that it would be parallel to his forearm, running in a single line of numbers. The pictures on the Internet had shown her that much. Just as they’d shown her other tattoos, in other colors and patterns—

Those images she pushed from her mind, as she continued to search for his tattoo...the one he hadn’t asked for, given by people who’d forced him to get it. It seemed like they were routinely put on the left arm...there. Under a myriad of veins, liver spots, old scars, and crinkly darkish hair. A series of numbers, faint, spread, bleached to a delicate shade of baby-blue by decades of exposure to sunlight.

It would have been fairly easy to remove with a laser, even though blue (along with yellow) was a difficult color to obliterate entirely with laser light, since it was so old and faded to being with. That was what she wanted to ask him about, why he didn’t have it taken off. Or cut out of his skin, then stitch together the gaping ends. This was not the sort of tattoo one would want to keep...but, as she held his cooling arm in her hands, she remembered how she considered herself part of a tribe, and realized that she wouldn’t need to have that question answered, after all.

For a few brutally clear moments, she simply stood in Mr. B.’s room, taking in his world as he’d lived it for the last she didn’t know how many years: Nubby orange drapes, fronting a window whose panes were swirled with old dust and unknown fingerprints. Peachy-pale walls, decorated only with a freebie calendar from the local savings-and-loan and a pair of framed prints of enlarged gladiola blossoms. Bedside table in faux dark wood. Plastic-upholstered chair, with tapering round legs. Well-worn linoleum flooring. A small bathroom off the right side of the bed. Not a ghetto, but not a place for a human being, either.

In a place like that, one would need to hang onto anything which reminded one of his or her basic humanity. Even if it was a reminder of a less-than-human designation....

With a rubber-kneed jolt, she’d reached the subtropolis. As the elevator doors slid open, the silver-walled coolness inherent in the native limestone walls and ceiling cocooned her within her abaya. In the distance, she was only slightly aware of the people milling around outside the many units beyond the elevator, some huddled around tables like café patrons in France, smoking and talking over coffee, others driving those little golf-cart-like put-puts, all of them making noise, even as none of the sounds really reached her.

Within the twenty miles worth of tunnels and storage units before her was the huge unit (big-enough-to-have-its-own-ZIP-code-huge) which housed the flash-scraps for the eastern part of the United States. All hermetically-sealed within special glass plates, and stored within a climate-controlled environment. Rows upon rows of surgically-removed flash: Whole Irezumi body tattoos, spread out hunting-trophy style; individual sections of skin, embellished with greywork portraiture so finely rendered it resembled pen-and-ink work on parchment; examples of virtually every cartoon character ever inked on a body part—including licensed characters doing things their creators never intended them to do; celebrity tattoos; a few examples of medical tattoos (breast reconstructions, radiation-therapy dots)...and an entire block’s worth of wall-mounted flash defined as “Unclassified.” Things inked on bodies whose meaning was only known to the wearer...words, names, images indefinable.

Gwynn had personally carried dozens of pieces to the storage unit, and she had tiny renderings of each bit of flash done in miniature on her own forearm. “Buncha little thoughts” Mr. B. had called them.

She hadn’t had time to think before she’d harvested his tattoo; luckily, there was a pair of small scissors in the bathroom, for cutting bandages. Technically, she’d had to stab his arm, then keep cutting, thankful that a non-beating heart pumps no blood. She didn’t want to look at what the arm looked like, after she’d peeled away the tattoo; she’d bandaged it sloppily, just enough to cover the wound she’d left. Let the person who officially found him think he’d had some procedure done. She didn’t plan to be around for them to ask her about it; Mr. Beniamino had been right. She wasn’t here because she wanted to be, she only stayed because no one else would have her. Because of her skin, because of her choices.

Because no other nurse would be able to look at those faded, wrinkled, sagging bodies whose former designs now melted into their epidermis, distorted by age and gravity into something akin to a badly-fitting leotard, rather than once-beautiful, once proud bodies. Like that woman down the hall, whose entire body was a series of garments, a pair of jeans, a purple- and brown-spotted shirt, even the pattern of socks on her feet. Never quite naked, even as she was never clothed enough.

But from now on, some other nursing assistant would have to look at them. Appreciate them, maybe.

Moving purposefully down an often-trod corridor, her black robe hazily reflected in the silver-painted walls, Gwynn headed for the Flesh-Vault, as it was properly known, and as she walked, those images from the Shoah website returned to her...those lampshades made of a man’s chest-flesh, the pattern preserved in taut, well-lit perfection. And other chunks of tattooed flesh, hacked out, and kept for the enjoyment of camp guards. One of their wives collected flash. Somehow, somewhen, people had forgotten that, though. How, Gwynn wasn’t sure, but somehow, the whole concept of taking a tattoo off a body and keeping it became acceptable, advantageous. True, these were voluntary donations, but how was that different from involuntary donations...some made for the sake of harvesting the tattoo, period?

They’re too beautiful to put in the ground, too beautiful to burn. Couldn’t you say that about the whole body, too?

There was a flypaper doormat before the entrance to the Flesh-Vault, and reflexively Gwynn slid her feet across it, before palming open the door pad. The man who worked as the main attendant, who had renamed himself Agnimukha, an East Indian word for “face of fire” in honor of his full-face tongues of flame tattoo, looked up from his security monitor, and said, “Forget the cooler on the bus?”

Pulling off the abaya with a quick rustle of scratchy black cotton, and leaving her hair in a flattened mass on her forehead, Gwynn shook her head, before ripping the packet of flash-scrap off her belly with a moist snick of duct-tape parting quickly from her hot flesh.

“Whoa...contraband flash. Cool. Haven’t seen any of that in months—”

“File this under ‘Historical’...here’s the fee.”

She placed the packet on the counter, and unfolded the surrounding foil. In the colorless overhead lights, the narrow sliver of flesh was wholly unlike any flash-scrap she’d ever seen before. Legally harvested flash was shaved clean, supple, neatly cut around the edges. Even Agnimukha was silenced by the sight of that ribbon of lightly-haired flesh, lying vulnerable and pale on the reflective foil. The numbers were barely legible, and sloppily applied. Gwynn didn’t want to think about how young Mayir Beniamino had to have squirmed and fought as they were applied. Finally, Agnimukha picked the flash up by the foil and started to carry it toward the back of the unit, where the people who processed and mounted the tattoos between glass worked. Gwynn had never seen those people, didn’t want to.

The attendant was halfway to the processing room when he turned around and said, “Hey, Gwynn...betcha you aren’t going to get this flash done on your arm to commemorate the run, are you?”

Bundling up her abaya under one arm, Gwynn thought about it for a few seconds, then—without putting the abaya over her head for the return trip to the surface of the facility, as she usually did—replied, “Of course I am. Why wouldn’t I?” before walking out of the vault, her body reflected brightly on the surrounding painted limestone walls.

AUTHOR’S NOTE TO “FROM THE WALLS OF IREZUMI”

The underground storage facilities mentioned in this story do exist, although at this time neither of them currently stores excised tattoos. The removal and preservation of some Irezumi Japanese full-body tattoos has been done, with the resulting excised tattoos being preserved between sheets of glass. And human skin lampshades using tattooed flesh from concentration camp inmates were made during World War II, just as all people sent to the camps were tattooed with identification numbers, just as described in the story.

AFTERWORD TO “FROM THE WALLS OF IREZUMI”

There’s a certain degree of disconnect between me and this story: some of the circumstances behind the publication were emotionally difficult for me, with the 9/11 attack being the worst. This story was written pre-9/11, and was scheduled to appear in the early winter of 2002, but it was moved up a few months to appear shortly after 9/11 (due to the references to Muslim clothing/culture, I suppose) and I wasn’t able to do what I felt was a necessary re-write regarding the events of 9/11—basically, my argument for a rewrite was this: 9/11 was a watershed event (something quite apparent within hours of its occurrence), and thus, some brief mention of it needed to be made within the text of the story. The argument didn’t fly with my editor, the story ran as-is, and in protest I yanked it from Nebula consideration. Which needless to say didn’t sit well with the editor.

What was I planning to add to the story? A brief passage during the scene when Gwynn speaks to the Muslim lady in Kansas City, which would have clarified why the woman might have been grateful for Gwynn treating her so civilly, considering how people still felt after 9/11. Which I still think was necessary in the story—I had toyed with the idea of inserting it after the fact, but too many people (I assume) already read the story as-is, so I decided, why bother after all this grief over it back when it first appeared? But that’s what I had in mind. No more than a sentence or two.

A few years before the story was written, I had a Muslim student who took the writing school course I used to teach (which I was fired from three days before Christmas in 1997 because I wasn’t able to do lessons on a computer, but I refused to just hand over all my current students and quit on the spot, so I stayed on until 2000), and she and I had discussed tattoos and the Muslim view of them—those written exchanges formed the core of the Kansas City scene in the story. I didn’t mention the student’s name because I felt she deserved her privacy, but I did enjoy working with the woman during my last few years teaching writing via correspondence course. And she did have an influence on the story, a positive one, I hope.

There is one other thing I do want to address, mainly for the benefit of those readers who are familiar with the Holocaust. Most children under working age (their early teens or so) were automatically shunted off to the showers, or some other form of automatic death. Save for twins—under certain circumstances (namely, the appearance of identical twins arriving at a camp), very young children were allowed to enter the camps...and for them, being tattooed against their will was the most minor of violations visited upon them. And one child was often used as the control subject, thus giving him or her a slightly better chance of surviving until the liberation of his or her fellow inmates....