Читать книгу UVF - Aaron Edwards - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

THE TWO BILLYS

‘Only the dead are safe; only the dead have seen the end of war’

George Santayana, Soliloquies in England and Later Soliloquies.1

The blistering warmth of the summer’s day made sitting indoors uncomfortable; probably one of the reasons why people had started to mill around in the shade. As the funeral cortège passed by, throngs of burly men joined the ranks of the mourners. Six neatly turned out pall-bearers sporting black trousers, white shirts and skinny black ties clasped arms as they shouldered the pristine oak coffin, which had been carefully dressed with the familiar paramilitary trappings of the purple-coloured Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) flag, coal-black beret and shiny brown leather gloves. Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) leader David Ervine brushed past me, as he barged into the swollen ranks of paramilitary types, young and old, many of whom fell back into line briskly, with little fuss.

A sea of grimacing, solemn faces pushed silently into the light breeze as the sound of semi-marching feet trudged along keeping time to a lone piper’s lament. As the medieval noise of the pipes gathered to a crescendo, the mourners congregated outside the tiny Baptist church. Standing proud at the foot of the railway bridge, the poky little church was the focal point of the exclusively Protestant working-class housing estate overshadowed by Carnmoney Hill, a commanding, undulating feature that presides over everyday life in this part of Northern Ireland.

The funeral on this occasion was for prominent loyalist Billy Greer, who had been a leading member of the outlawed UVF and a former PUP councillor on Newtownabbey Borough Council. Greer was a popular figure, a larger-than-life character held in high esteem by his fellow councillors and by a legion of supporters in the local community. During his tenure on the local authority he had even met Prince Charles, on one of his many visits to the area; a photo of Billy bowing to the heir to the throne still hangs in the social club he chaired for over a generation. Greer lived in Monkstown all his life except, of course, for the time he spent incarcerated for UVF membership, in the compounds of Long Kesh in the 1970s. Those close to Greer admired how he had worked tirelessly for those who resided in this fiercely working-class housing estate. As a consequence of the PUP’s effective voting management, he was elected in University Ward in 1997 with 448 First Preferences votes.2 Greer was a strong believer in the community spirit that lay at the heart of the UVF’s support base in areas like this across Northern Ireland. Consequently, Monkstown was synonymous with Billy Greer and the UVF; it would now turn out en mass to give him a good send-off.

On the day of Greer’s funeral, I was enrolled as chauffeur to three UVF veterans. It was a glum occasion. As such, the car was loaded up with an eclectic mix of former gunmen and auxiliaries who counted Greer as one of their ‘team’, a comrade from ‘the old days’. As the men spoke they seemed to have captured their memories of their friend in a bubble of surreptitious remembrance. They painted a picture of a world inhabited by ‘goodies’ and ‘badies’, and they, they assured me, were firmly on the ‘right side’. ‘Ulster’, the men were at pains to tell me, ‘had then been under threat from militant republicans’, and this presaged first vigilantism, and then a military response. It meant that everyone needed to pull together for the good of the community; for the good of their country. It was also a time when almost everyone was armed and connected to one or other of the alphabetic spaghetti bowl of paramilitary organisations sprouting foot soldiers across the province. Northern Ireland became awash with weapons, blood and death during these years. Popularly known as ‘the troubles’, violence and murder had exploded onto the streets in the spring and summer of 1966, when the UVF perpetrated a handful of attacks across Belfast, Rathcoole and Carrickfergus.

Forty years almost to the day when the first UVF killings rocked Northern Ireland, the organisation was still in existence. There was nothing to indicate otherwise, in that it had murdered over thirty-two people since its 1994 ceasefire – almost all of them, bizarrely, from the Protestant community they claimed to be defending. Although the violence from all sides had wound down significantly, loyalists, it seemed, were stuck in a time warp; biding their time, and waiting for any excuse to return to war.

Over 3,700 men, women and children had tragically lost their lives over thirty years of political violence. And although the Provisional IRA murdered around 1,800 people before calling a halt to its campaign in 2005, the UVF contributed significantly to the overall body count, killing somewhere in the region of 564 people and injuring many more.3 Its founding members claimed at the time that it had originally been formed to oppose the perceived threat posed by the IRA, though they later admitted that the UVF was really a tool of political intrigue utilised by a handful of faceless right-wing unionist politicians. The irony that the UVF pre-dated the Provisional IRA and had now outlasted its old foe was not lost on me, as I watched the organisation bury one of its leading lights on that piping hot summer’s day.

As I edged my way into the crowd, which had by now assembled according to their importance inside the organisation’s hierarchy, I searched for a friendly face. Even though I had been born and reared in the area, and was known by those connected to the organisation for my voluntary work on a UVF-endorsed conflict transformation process aimed at its disarmament and eventual departure from the ‘stage’, I was a non-member – a civilian – and therefore counted very much as an outsider, at least in public.

The more senior UVF veterans, all men in their 50s, 60s and 70s, sharply drawn frowns and rugged faces, sloped in behind the family circle of their fallen comrade. All the top brass had turned out – from the leader of the organisation, the so-called Chief-of-Staff, known to his close confidants as ‘The Pipe’, through to his headquarters staff and a sprinkling of local commanders from across the province. There seemed to be more chiefs than Indians in attendance. All of them dressed in smart suits and sensible shoes, even if some of them insisted on the addition of not-so-sensible white socks. The sweet smell of cheap deodorant and aftershave wafted through the air, as beads of sweat dripped beneath the arms of the stockier members of the crowd. They had now formed up, ready to see off their fallen comrade.

By now the piper’s lament had been drowned out by the sobbing of Greer’s wife, family and close friends, all of whom were now emotionally gathered round the coffin as it paused under the mural painting of the iconic charge of the 36th (Ulster) Division at Thiepval Wood in the first Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916. Billy had prided himself on the upkeep of the mural, and it would become a shrine to him when he died.

Militarists led politicos, with many of the latter having worked with the dead loyalist when he was the chairman of the PUP’s East Antrim Constituency Association, the UVF’s political associates. A member of the UVF since 1968, he was a commander of the group’s powerful East Antrim Battalion from the mid-1970s until it amalgamated with North Belfast in the mid-1990s. Prior to its amalgamation with North Belfast, Billy Greer was asked by the UVF leadership to join the PUP talks team in the mid-1990s as a means of selling the loyalist ceasefire to the organisation’s rank-and-file. Greer inhabited a place within the UVF that – in equivalent terms – was reserved only for the likes of Bobby Storey in the republican movement. In other words, Greer was a key grassroots figure, a man of stature and influence, the proverbial ‘UVF man’s UVF man’, that ranks of volunteers looked up to and followed out of a mixture of fear and adulation. When Billy Greer attended the multi-party talks in 1997/98, he was not attending as a PUP member per se but as the UVF Brigade Staff’s plenipotentiary.

When he died, Billy was no longer the deputy commander of the UVF’s East Antrim and North Belfast brigade. He had tendered his resignation to ‘The Pipe’ over the activities of some of his colleagues on the local command group who had gone against Brigade Staff policy. Following an internal investigation, Billy, his brigadier and long-time friend sixty-year-old Rab Warnock, and their team were replaced by a relatively unknown UVF man called Gary Haggarty. It was a choice that would have huge repercussions for the organisation as it sought to dismantle its paramilitary structures over the next decade.

That Greer was held in such high esteem meant that few people questioned why the organisation had not taken more stringent action against the leadership around Warnock, especially in light of the seriousness of the allegations levelled against them. He still remained chairman of the local social club, an indefatigable presence who dominated working-class life in the district, just as prominently as the Napoleon’s Nose feature jutting out of Belfast’s Cave Hill Mountain, which could be seen some way in the distance towering above the city. Billy knew everybody and everybody knew Billy. Nothing, except death it seemed, could remove him from the place he called his home for over half a century. Greer had been the quintessential community activist, frequently interviewed by local newspapers, whether it was about his campaign of dispensing free personal alarms for the elderly or urging the removal of unsightly paramilitary murals in Newtownabbey.

It was his positive contribution to returning this place to some semblance of normality that left people aghast when they learned of the extent of the actions of the area’s UVF leadership. I had heard that some of these men had joined the UVF for political reasons, while others were there to line their own pockets. Greer had been in the former category. He had joined the UVF at the very beginning, prior to the outbreak of the troubles, and he would later rise to prominence in the 1970s, when the IRA began its armed campaign. Now, three decades later, he had fallen on his sword for the men around him. In the two years after he was replaced, Billy became a different man. He stopped drinking and, though he was still the life and soul of the company he kept, he had become isolated inside the organisation he loved.

On the day of his funeral, though, he was just another fallen comrade. The UVF had put its internal squabbles aside and forged a united front. A clear signal was being sent out. Whatever had happened in the past had now been consigned to the dustbin of history, of relevance only to the naysayers who had a vested interest in derailing the accomplishments of the UVF’s internal consultation process. The strife wracking the inner circles of the UVF died with Billy Greer, or so it seemed on this occasion. In time, a different story would emerge, one more complicated than people realised. It would leave little doubt in some people’s minds that Greer’s departure from the leadership of the East Antrim UVF was seen by some as a cynical attempt to reverse the UVF’s decision to move towards a permanent disengagement from political violence.

***

Seven days after Billy Greer died, another former UVF leader passed away. His name was Billy Mitchell. At one time he had also commanded the East Antrim UVF and, subsequently, became a member of the group’s ruling Brigade Staff. Like Greer, I knew Billy Mitchell very well. He had been a mentor to me as we worked together on peace-building projects in the divided communities across Belfast and East Antrim in the last years of his life. If Billy Greer imbibed the UVF’s militaristic ethos throughout his entire life, Billy Mitchell embodied the political dynamism of a far-reaching catharsis that took him on a personal odyssey from militarist to politico.

‘How could you not like Billy,’ said ‘The Craftsman’, said to be one of the top two most senior UVF Brigade Staff officers. Like Mitchell, The Craftsman became involved in militant loyalism sometime in 1966 in the belief that the IRA were about to launch an armed coup to take over the government of Northern Ireland and subsume it into an all-island republic. It was astonishing to think that in the same year Beatlemania was sweeping the world, when Carnaby Street represented a new departure in British culture and when the world was changing dramatically amidst a Cold War, old shibboleths were returning with great vigour in Northern Ireland. Mitchell’s route to embracing extremist views began when he came under the spell of Reverend Ian Paisley, a fundamentalist Protestant preacher, though he had already been indoctrinated into loyalism by way of other, less prominent, religious extremists who belonged to the Flute Band he joined in his early twenties. Born in Ballyduff in 1940, Billy’s father died soon afterwards and the family went to live with his mother’s parents on the Hightown Road, close to Belfast’s Cave Hill. By 1974 Mitchell was on the UVF’s Brigade Staff, the only non-Shankill man ever to have served in that capacity. ‘I couldn’t tell you what role he played on Brigade Staff,’ The Craftsman told me. ‘I remember Billy turned up to a Brigade Staff meeting in the 1970s in his overalls. I think he worked [as a truck driver] at the time. He had the air of a country man about him.’ It is likely that Mitchell served as the organisation’s Director of Operations, following the death of Jim Hanna in April 1974. That he commanded one of the most active units inside the UVF meant he had a foot in both the Shankill and East Antrim.

When Mitchell was arrested by the Security Forces in Carrickfergus in March 1976, he had ring binders full of information used by the UVF for targeting. He told detectives that there was an innocent explanation for the material found in his possession. The truth was that he was double-hatted as the UVF’s Director of Intelligence at the time, responsible for targeting his organisation’s enemies, wherever they were to be found. Unbeknown to the CID detectives who questioned him, they had arguably the UVF’s most important leader in their custody. Here was the organisation’s top strategist, its chief scribe and its quintessential man of action. It is rare for guerrilla or terrorist organisations to have men who possess both the military aptitude and the political astuteness in their ranks. It is even rarer for them to be concentrated in one person.

During his long period of incarceration between 1976 and 1990, Mitchell spent his time wrestling with his conscience and attempting to unravel the puzzle of what had propelled him into the ranks of the UVF. After a few years, he would come to reject his paramilitary past, commit himself to Christianity and give up his coveted Special Category Status to enter the newly constructed H Blocks as a Conforming Prisoner in the early 1980s. There was little Billy conformed to. He had been a senior UVF commander who had been responsible for leading the organisation through its darkest years, when it was responsible for murdering several hundred people, thirty-three of whom were killed in a single day in bomb attacks on Dublin and Monaghan. He had even talked to the highest-ranking members of both wings of the Official and Provisional IRAs. It was part of the UVF’s twin track of ‘talking and killing’ he told me thirty years after those turbulent events. Yet, by 1979, he had given all of that up.

When he emerged from prison in 1990, Billy dedicated himself to rebuilding the communities the UVF had helped to shatter with their violence. He was committed to this and, as one of his friends would remark in his funeral oration, not only did he ‘walk the walk but he demanded that people walked with him’. This was the Billy Mitchell I knew. The man who could in one room bring together sworn enemies from across a deeply divided community. IRA members, UVF members, Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) members, even some from the so-called dissident hinterland – all had come into contact with him in his years as a peace-builder. It is little wonder, therefore, that as people gathered to pay their final respects to Billy Mitchell at his funeral service, they represented the broad spectrum of Northern Irish society.

As we look back on its fifty-year history, we see that the history of the UVF is a very rich and complicated one. It is at its heart a story of ordinary men like the two Billys, Greer and Mitchell, who became involved in paramilitary activity for a variety of reasons. They both rose to prominence through their ability to get the men and women under their command to do things they wouldn’t have otherwise done. Yet, their stories also demonstrate why some individuals remain involved in militarism, while others go against the grain and ask serious questions of what had brought them to the point where they advocated, planned and participated in violent acts.

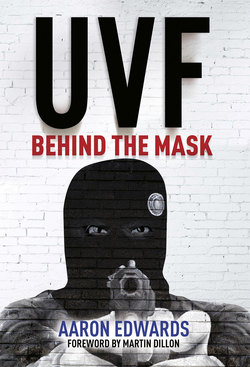

This book charts the shifting contours in Ulster loyalism, and explains how and why men like these came to make the choices they did and what the consequences were for the world around them.