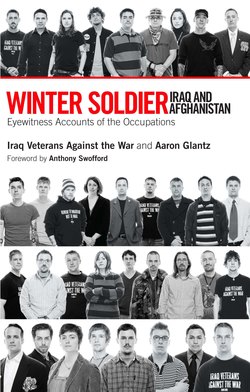

Читать книгу Winter Soldier: Iraq and Afghanistan - Aaron Glantz - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSergio Kochergin

Corporal, United States Marine Corps, Rifleman First Battalion Seventh Marines Scouts Sniper Platoon

Deployments: February 2, 2003–October 2, 2003, from Kuwait to Baghdad;

August 27, 2004–March 20, 2005, along the Syrian border

Hometown: Eugene, Oregon

Age at Winter Soldier: 23 years old

Our area of operation was near Vincent Emanuele’s, along the Syrian border. It was a little base. The town was not secure when we arrived, and the initial Rules of Engagement were if a person had a weapon, or there’s suspicious activity going on, we had to call the commanding post, request permission, assess the situation, and see what we were going to do.

The third day after we arrived, our company commander, our first lieutenant, and one of our NCOs all got killed by an IED. As time went on, and as the casualties grew in number, the Rules became lenient. Because we saw our friends getting blown up and killed every day, we didn’t really question them. We were angry. We just wanted to do our job and come back

We used “drop weapons.” Drop weapons are the weapons that were given to us by our chain of command in case we killed somebody without weapons so that we would not get into trouble. We would carry an AK-47 and if the person that was shot did not have the weapon, the AK-47 would be placed at his corpse. Then, when the unit would come back to the base they would turn it in to identify the shot man as an enemy combatant. The weapons could not come from anyone else but the higher chain of command because after a raid all the weapons are turned into the armory and should be recorded.

The Rules of Engagement were very flexible. After our own casualties mounted the Rules changed. We were allowed to engage anyone with a weapon without calling in and asking permission from the higher command. Two months into the deployment our Rules were to engage any personnel with a heavy bag and a shovel at the intersections or on the roads. This gave us a bigger window on who we can engage. Looking at the situation from this point of view a lot of the enemy combatants that we shot were really civilians in the wrong place at the wrong time.

One of our intelligence officers told us that they received a call from one of the sources in the city, telling them that there were flyers posted all over the town that said that there were unknown snipers in the city that kill the insurgents and the civilians. We did not take into consideration that these innocent people were being killed by us, because every time we sent the pictures to the command post through an interlink system, we would receive an approval to kill people with shovels and heavy bags. Now I know that it was not right to do that, but when you trust those who act like they care for you, you listen to them and follow their orders because you don’t want to let your friends down. “What if…?” was used as propaganda and a way to relieve our minds from the actions we have partaken in and make it easier on us.

Finally, I want to tell you is about a roommate who we shared the bathroom with back in the United States. He was on the suicide watch for a few months on and off. The last three weeks before we deployed he was constantly on the watch. A week before a family day he was released from the watch so that he would not say anything to his parents and he did not say anything to them. About a month into the deployment he blew his brains out in one of the shower stalls. Actions like that show the poor judgment of our command who don’t care for the troops just to save their own skin. That marine should have not gone to Iraq in the first place and nobody was held responsible for his death. If they do not care for their own marines what care do they have for the people of Iraq when they give the orders?

I want to apologize to all the people in Iraq. I’m sorry, and I hope this is going to be over as soon as possible.