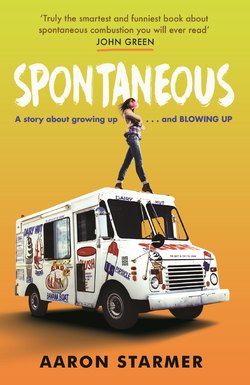

Читать книгу Spontaneous - Aaron Starmer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеhow it started

When Katelyn Ogden blew up in third period pre-calc, the janitor probably figured he’d only have to scrub guts off one whiteboard this year. Makes sense. In the past, kids didn’t randomly explode. Not in pre-calc, not at prom, not even in chem lab, where explosions aren’t exactly unheard of. Not one kid. Not one explosion. Ah, the good old days.

Katelyn Ogden was a lot of things, but she wasn’t particularly explosive, in any sense of the word. She was wispy, with a pixie cut and a breathy voice. She was a sundress of a person—cute, airy, inoffensive. I didn’t know her well, but I knew her well enough to curse her adorable existence on more than one occasion. I’m not proud of it, but it’s true. Doesn’t mean I wanted her to go out the way she did, or that I wanted her to go out at all, for that matter. Our thoughts aren’t always our feelings; and when they are, they rarely last.

On the morning that Katelyn, well, went out, I was sitting two seats behind her. It was September, the first full week of school, an absolute stunner of a day. The windows were open and the faraway drone of a John Deere mixed with the nearby drone of Mr. Mellick philosophizing on factorials. Worried I had coffee breath, I was bent over in my seat, digging through my purse for mints. My POV was therefore limited, and the only parts of Katelyn I saw explode were her legs. Actually, it’s hard to say what I saw. Her legs were there and then they weren’t.

Wa-bam!

The classroom quaked and my face was suddenly warm and wet. It’s a disgusting way to say it, but it’s the simplest way to say it: Katelyn was a balloon full of fleshy bits. And she popped.

You can’t feel much of anything in a moment like that. You certainly can’t analyze the situation. At least not while it’s happening. Later, the image will play over and over in your head, like some demon GIF, like some creeper who slips into your bed every single night, taps you on the shoulder, and says, “Remember me, the worst fucking moment of your life up to this point?” Later, you’ll feel and do a lot of things, but when it’s actually happening, all you can feel is confusion and all you do is react.

I bolted upright and my head hit my desk. Mr. Mellick dove behind his chair like a soldier into the trenches. My red-faced classmates sat there in shock for a few moments. Blood dripped down the windows and walls. Then came the screaming and the obligatory rush for the door.

The next hour was insane. Hunched running, hands up, sirens blaring, kids in the parking lot hugging. News trucks, helicopters, SWAT teams, cars skidding out in the grass because the roads were clogged. No one even realized what had happened. “Bomb! Blood! Run for the fucking hills!” That was the extent of it. There was no literal smoke, but when the figurative stuff cleared, we could be sure of only two things.

Katelyn Ogden blew up. Everyone else was fine.

Except we weren’t. Not by a long shot.

let’s be clear

This is not about Katelyn Ogden. She was important—all of them were—but she was also a signpost, a starting point on a path of self-discovery. I realize how corny and conceited that sounds, but the focus of this should be on me and what you ultimately think of me. Do you like me? Do you trust me? Will you still be interested in me after I say what I have to say?

Yes, yes. I know, I know. “It’s not important what people think of you, it’s who you are that counts.” Well, don’t buy into that crap. Perception trumps reality. Always and forever. Simply consider what people thought of Katelyn. Mr. Mellick once told Katelyn that she “would make an excellent anchorwoman,” which was a coded way of saying that she spoke well and, though it wasn’t clear if she was part black or part Asian or part Hispanic, she was pretty in a nonthreatening, vaguely ethnic way.

In reality, Katelyn Ogden was Turkish. Not part anything. Plain old Turkish. Her family’s original name was Özden, but they changed it somewhere along the line. Her dad was born right here in New Jersey, and so was her mom, but they both had full Turkish blood that went back to the early Ottoman Empire, which, as far as empires go, was a pretty badass one. Their armies were among the first to employ guns and cannons, so they knew a thing or two about things that go boom.

Katelyn’s dad was an engineer and her mom was a lawyer and they drove a Tahoe with one of those stick-figure-family stickers on the back window. Two parents, one kid, two dogs. I’m not entirely sure what the etiquette is, but I guess you keep the kid sticker on your window even . . . after. The Ogdens did, in any case.

I learned all the familial details at the memorial service, which was closed casket, for obvious reasons, and which was held in State Street Theater, also for obvious reasons. Everyone in school had to attend. It wasn’t required by law, but absences would be noted. Not by the authorities necessarily, but by the kids who were quick to label their peers misogynistic assholes or heartless bitches. I know because I was one of those label-happy kids. Again, I’m not necessarily proud of that fact, but I certainly can’t deny it.

The memorial service was quite a production, considering that it was put together in only a few days. Katelyn’s friend Skye Sanchez projected a slideshow whose sole purpose was to remind us how ridiculously effervescent Katelyn was. There was a loving eulogy delivered by a choked-up aunt. A choir sang Katelyn’s favorite song, which is a gorgeous song. The lyrics were a bit sexy for the occasion, but who cares, right? It was her favorite and if they can’t play your favorite song at your memorial service then when the hell can they play it? Plus, it was all about saying good-bye at the wrong moment, and at least that was appropriate for the occasion.

There’s a line in it that goes, “your hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm …” Katelyn’s hair was short and dark, the furthest thing from sleepy and golden, but that didn’t matter to Jed Hayes, who had a crush on her going all the way back to middle school. That hair-upon-the-pillow line made him blubber so loud that everyone in the balcony felt obligated to nod condolences at the poor guy. His empathy seemed off the charts, but if we’re being honest with ourselves—and we really should be—then we have to accept that Jed wasn’t crying because he truly loved Katelyn. It was because her storm of hair never hit his pillow. Sure, it’s a selfish thing to cry about, but we all cry about selfish things at funerals. We all cry about “if only.”

• If only Katelyn had made it through to next year, then she would have gone to Brown. She was going to apply early decision and was guaranteed to get in. No question that’s partly why her SAT tutor, Mrs. Carbone, was sobbing. All those hours, all those vocab flash cards, and for what? Mrs. Carbone still couldn’t claim an Ivy Leaguer as a past student.

• If only Katelyn had scammed a bit more cash off her parents, then she would have bought more weed. It was well-known among us seniors that Katelyn usually had a few joints hidden in emptied-out mascara tubes that she stashed in the glove box of her Volvo. It was also well-known that she was quickly becoming the drug-dealing Dalton twins’ best customer. Such a loss was surely why the Daltons were a bit weepy. Capitalism isn’t an emotionless endeavor.

• If only Katelyn had the chance to accept his invitation to the prom, then she would have ended up with her hair upon Jed Hayes’s pillow. It was within the realm of possibility. He wasn’t a bad-looking guy and she was open-minded. You couldn’t begrudge the kid his tears.

That’s merely the beginning of the list. The theater was jam-packed with selfish people wallowing in “if only.” Meanwhile, outside the theater, other selfish people had moved on and were already wallowing in “but why?”

As you might guess, when a girl blows up in pre-calc and that girl is Turkish, “but why?” is fraught with certain preconceived notions. It can’t be “just one of those things.” It has to be a “terrorist thing.” That was what the cable-news folks were harrumphing, and the long-fingernailed women working the checkout at Target were gabbing, and the potbellied picketers standing outside the theater were hollering.

Never mind the fact that no one else was hurt when Katelyn exploded. We were all examined. Blood was taken. Questions were asked. Mr. Mellick’s class was considered healthy, if not in mind, then in body. We were considered innocent.

Never mind the fact that there wasn’t a trace of anything remotely explosive found in the classroom. The police did a full sweep of it, the school, Katelyn’s house, the nearest park, and a halal restaurant two towns over. They didn’t find a thing. FBI was there too, swabbing everything with Q-tips. Collective shrugs all around.

Never mind “if only.” A girl with so much potential doesn’t suicide-bomb it all away. She just doesn’t. Sure, she smoked weed, and if the rumors were true, she was slacking off in pre-calc and fighting with her mom, but that’s not because senior year was her year to blow things up. It was her year to blow things off, perhaps her last chance in life to say fuck it.

It was a lot of people’s last chance to say fuck it, as it turned out.

how you feel

To describe how you feel after a girl explodes in your pre-calc class is a tad tricky. I imagine it’s similar to how you feel when any tragedy comes hurtling into your life. You’re scared. You’re fragile. You flinch. All the time. You may have never even thought about what holds life together. Until, of course, it comes apart.

Same with our bodies. You can imagine cancer and other horrible things wreaking havoc on our doughy shells, but you don’t ever expect our doughy shells to, quite literally, disintegrate. So when the unimaginable happens, when the cosmos tears into your very notion of what’s possible, it’s not that you become jaded; it’s that you become unsure. Unsure that you’ll ever be sure about anything ever again.

You get what I’m saying, right? No? Well, you will.

For now, maybe it’s easier to speak about practicalities, to describe what exactly happens after a girl explodes in your pre-calc class. You get the rest of the day off from school, and the rest of the week too. You talk to the cops on three separate occasions, and Sheriff Tibble looks at you weird when you don’t whimper as much as the guy they interviewed before you. You are asked to attend private therapy sessions with a velvet-voiced woman named Linda and, if you want, group therapy sessions with a leather-voiced man named Vince and some of the other kids who witnessed the spontaneous combustion.

That’s what they were calling it in the first few weeks: spontaneous combustion. I had never heard of such a thing, but there was a precedent for it—for people catching fire, or exploding, with little-to-no explanation. Now, unless you’ve been living in the jungles of New Guinea for the last year, you already know all this, but if you want a refresher on the history of spontaneous combustion, head on over to Wikipedia. Skip the section on “The Covington Curse” if you want the rest of this story to be spoiler-free.

From Linda, I learned that it was normal to feel completely lost when a girl spontaneously combusts in your pre-calc class. Because in those first few weeks I’d find myself crying all of sudden, and then making really inappropriate jokes the next moment, and then going about the rest of the day like it was all no big deal.

“When something traumatic happens, you fire your entire emotional arsenal,” Linda told me. “A war is going on inside of you, and I’m here to help you reload and make more targeted attacks. I’m here to help the good guys win.”

At the group sessions, Vince didn’t peddle battlefront metaphors. He hardly spoke at all. He simply repeated his mantra: “Talk it out, kids. Talk it out.”

So that’s what we did. Half of us “kids” from third period pre-calc met in the media room every Tuesday and Thursday at four, and we shared our stories of insomnia and chasing away bloody visions with food and booze and all sorts of stuff that therapists can’t say shit about to your parents because they have a legal obligation to keep secrets.

Nutty as she was, Linda helped. So did Vince. So did the rest of my blood-obsessed peers, even the ones who occasionally called me insensitive on account of my sense of humor.

“Sorry, but my cell is blowing . . . spontaneously combusting,” I announced during a Thursday session when my phone kept vibrating with texts. It had been only six weeks since we’d all worn Katelyn on our lapels. In other words, too soon.

“I realize that jokes are a form of coping,” Claire Hanlon hissed at me. “But tweet them or something. We don’t need to hear them here.”

“Sorry but I don’t tweet,” I told her.

That said, I did fancy myself a writer. Long form, though. I had even started a novel that summer. I titled it All the Feels. I think it was young adult fiction, what some might call paranormal romance. I didn’t care, as long as I could sell the movie rights. Which didn’t seem like an impossibility. The story was definitely relatable. It was about a teenage boy who was afraid of his own emotions. In my experience, that summed up not only teenage boys, but teenagers in general. Case in point:

“This is a healing space and that makes it a joke-free zone,” Claire went on. “I don’t want to relive that moment and you’re liable to give me a flashback.”

“I like Mara’s jokes,” Brian Chen responded. “They help me remember it’s okay to smile. I don’t know if I’d still be coming to these things if it wasn’t for Mara.”

“Thank you, Bri,” I said, and at that point I began to realize that we were a bit of a cliché. Stories about troubled teenagers often feature support groups where smart-ass comments fly and feelings get hurt, where friends and enemies are forged over one-liners and tears. But here’s the thing. Even if we were a bit of a cliché, we were only a cliché for a bit. Because almost immediately after announcing his dedication to my humor, Brian Chen blew up.

sorry

I did that on purpose. I didn’t give you much of a chance to know Brian and then I was all, like, “Oh yeah, side note, that dude exploded too.” I understand your frustrations. Because he seemed like a nice guy, right? He was. Undoubtedly. One of the nicest guys around. He didn’t deserve his fate.

That’s the thing. When awful fates snatch people away, sometimes it happens to someone you know a little and sometimes it happens to someone you know a lot, and in order to shield yourself from the emotional shrapnel, it’s better to know those someones a little. So I was trying to do you a solid, by getting the gory details out of the way from the get-go. Unfortunately, you won’t always have that luxury. Because to understand my story, you’re going to have to get to know at least a few people, including a few who blow up.

A bit about Brian, because he deserves a bit. He was half Korean and half Chinese. I’m not sure which half was which, which is racist I guess. I don’t doubt that Brian knew that Carlyle is an English name while McNulty is an Irish name, but all these months later and I still can’t be bothered to find out if Chen is Korean or Chinese in origin. I know. I’m a total dick. As I said, I’m not necessarily proud of it.

Thing is, I liked Brian. I even kissed him once. On the eighth grade trip to Washington, DC, we were in the back of the bus and he rested his head on my shoulder. We weren’t good friends or anything, but it was one of those moments. Hot bus. Long drive. All of us tired and woozy.

When no one was looking, I kissed him on the lips. No tongue, but I held it for a couple of seconds. It was more than a peck. I did it because I thought it would feel nice. His lips seemed so soft. And it did feel nice. And soft. But Brian pretended to be asleep, even though it was obvious he was awake. My elbow was touching his chest and I felt his heart speed up. So I also pretended to be asleep, because that’s what you do when you kiss a guy and he pretends to be asleep. You follow suit, or you end up embarrassing yourself even more.

We went on with our lives after that. Went to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, the Washington Monument, the Pentagon. Then we went home. We didn’t talk about what I did. Which was fine by me. Brian didn’t spread rumors or try to take advantage of the situation. Like I said, one of the nicest guys around. He still smiled at me in the hall, used my name when he saw me.

“Good to see you, Mara.”

“How’d that bio test turn out, Mara?”

“Can I offer you a baby carrot, Mara?”

Brian liked baby carrots. Loved them, actually. Ate them all the time. Raw. Unadorned. No dip or peanut butter or anything to make them taste less carroty. He kept a bag of them in his backpack and munched his way through life. I don’t know if it was an addiction or a discipline, but either way you kind of had to respect it.

What you didn’t have to respect was that he wore the same pair of filthy neon-blue sneakers everywhere, even to dances and Katelyn’s memorial service. He called them his “laser loafers,” a term that didn’t catch on, as he’d obviously hoped it would. He’d gone viral once and figured he could harness that magic again. It doesn’t work that way, though.

Viral, you ask? The boy went viral? In a manner of speaking, yes. Because Brian Chen was the proud creator of Covington High’s favorite catchphrase: “Wrap it up, short stuff!”

It was dumb luck, really. He had first said it during a group presentation in English class when the five-foot-two-inch Will Duncan kept blabbing on and on about how sad it was that Sylvia Plath “offed herself by sticking her head in the oven because she was actually pretty hot, in addition to being crazy talented.”

“Wrap it up, short stuff!” Brian blurted out to shut his pal up and everybody lost their shit. By the end of the week, “Wrap it up, short stuff!” was something we said to long-winded people. Then we started hollering it at my parents’ deli to the guys who literally wrapped up the sandwiches. Then we started using it as shorthand for “please use a condom or else you’re gonna end up with a baby or a disease, basically something that will ruin your life.”

I know. Wrap it up, short stuff.

So, yeah, Brian Chen was a nice guy. A carroty guy with soft lips, filthy sneakers, and a catchphrase. Now you know him, and I hope you understand that when I make jokes about him and the other people who were here and gone in an instant, it’s because of a billion things that are wrong with me. But it’s not because they deserve it.

what was wrong with us

Here’s what happens when a guy blows up during your group therapy session that’s supposed to make you feel better about people blowing up. The group therapy session is officially canceled. You do not feel better.

What also happens is all nine remaining members of the group therapy session are escorted to the police station in an armored vehicle. With Katelyn, they let us shower before the cops got involved, but no such luck with Brian. It was too much of a coincidence. Same group of people, same wa-bam.

This wasn’t terrorism. Or, to be more accurate, Brian wasn’t a suicide bomber. Around here, nobody thinks an East Asian person would be a terrorist. Which is silly, really, because East Asia has plenty of terrorists. Back in the nineties, there were a bunch of Japanese terrorists who filled a subway station with poison gas and killed a shit-ton of people. No Turk has pulled off something that audacious, as far as I know. It’s definitely racist to think that Katelyn was a terrorist and Brian wasn’t.

But that’s what people thought. Or they thought someone else in our class was behind both incidents. So the cops shuffled us precalc, group-therapy saps into a conference room where we sat, bloody and stunned, under awful fluorescent bulbs that flickered every few seconds.

“Gahhh!” Becky Groves screamed as soon as the cops left us alone. They had gathered in the hall to talk to some FBI agents. To strategize, I guess.

“Let ’em cool their heels a bit,” they were probably saying as they blew on their coffee. “Get their stories straight and then, blammo, we’ll work the old McKenzie Doubleback on these perps.”

Yes, yes, I know, I know. There’s no such thing as the “McKenzie Doubleback,” but I’m sure they have names for their interrogation techniques.

Anyway, once Becky Groves was done screaming—which was a few seconds later because she’s Becky Groves and she has the lungs of a water buffalo—Claire Hanlon said, “So who did it?”

“Really?” I replied.

“Really!” Claire snapped. “The police know this can’t be a coincidence . . . and I know this can’t be a coincidence . . . and I know I didn’t do it . . . and so it has to be one of you.” An aneurysm seemed imminent the way Claire was panting out the words.

“How?” Malik Deely asked.

“However . . . people like you . . . do these sorts of things,” Claire said.

You don’t use the term “people like you” around people like Malik (that is, black people), but he had a cool-enough head to let logic beat out emotion.

“Seriously?” he said. “Seriously? There was no bomb. The guy’s chair was completely intact. Becky was sitting right next to him and she’s fine.”

“Gahhh!” Becky screamed again, this time with her eyes squeezed shut and her hands clawing at her frizzy red hair.

“Physically fine, I mean,” Malik said. “We all are. Something inside these kids just . . . went off.”

Greyson Hobbs, Maria Hermanez, Gabe Carlton, Yuki Dolan, and Chris Welch were all in the room too, but they weren’t saying anything. Their perplexed eyes kept darting back and forth as we spoke. It was like they were foreign tourists who’d stumbled into a courtroom. They weren’t trying to figure out who was innocent or guilty. All they wanted to know was “How the hell did we end up in this place? Which way is the way back to Disney World?”

When the door opened, those perplexed eyes all darted to Special Agent Carla Rosetti of the FBI. I would learn later that she wasn’t necessarily the best and brightest, but at that moment, compared to our schlumpy local boys-in-blue, she looked like the real goddamn deal.

She stood in the doorway decked out in a white shirt, dark blazer, dark pants, and dark pumps. Standard FBI attire, I assumed, though a bit baggier than what the chicks on TV rocked. The clothes were obviously chain-store bought, but from a nice chain store. Ann Taylor or something. Even without the outfit, her name was Carla Rosetti and how could she not be an ass-kicking federal agent with a name like that?

“Your parents are here to collect you,” Special Agent Carla Rosetti said as she stepped into the room. “But first you will be surrendering your clothing. There are showers and sweat suits. You’ll wash down, dress up, and go home. You’ll be hearing from us tomorrow morning.”

“No. You will be hearing from my lawyer. Tonight,” Claire said. “I have rights, you know?”

“I never said you didn’t,” Special Agent Carla Rosetti remarked. “I simply asked you to give me my evidence, evidence I obtained a warrant to collect. The alternative is to walk out the door and face some serious criminal charges, which I’m sure will delight your parents, especially after you’ve covered the interiors of their Audis with bloodstains. Kids have been getting changed for gym class for time immemorial. This is no more a violation of your rights than that. I’ll blow a whistle and force you to play dodgeball if that’ll make you feel more comfortable, though I’m not constitutionally obliged to.”

Special Agent Carla Fucking Rosetti.

in case you were wondering

Showers in police stations can burn the sun off a sunbeam, and sweat suits from police stations have pit stains the size of pancakes, but you don’t complain about those things, considering that you’ve lived through two spontaneous combustions. You simply go home washed and dressed in gray cotton and when your parents ask you what you need, you tell them you need to be alone, and they respect that, for the time being. Then you flop down on your bed with your laptop and you see the story invading every corner of the internet.

ANOTHER EXPLOSION ROCKS SCHOOL

MORE TERROR AT COVINGTON HIGH

WE RANK THE TOP TEN SPONTANEOUS COMBUSTIONS IN HISTORY

So you close your laptop and turn to your phone, which is blowing . . . spontaneously combusting. There are a ton from your friend Tess, but the last text that comes in is from a number you don’t recognize.

It says:

You were there for both of them. That must have been invigorating.

Not scary. Not sad. Not difficult.

Invigorating.

You should be creeped out, but you’re not. Because it’s the first time that someone gets it right. Both explosions were exactly that. Invigorating. A terrible thing to admit, but it’s in those moments of admitting and accepting your own terribleness that you realize other people can be terrible too. And if they can be terrible too, then maybe they can be vulnerable too, caring too, and all the things that you are and hope to be.

You fall in love, which is the stupidest thing you can ever do.

other stupid things that were done

Since I had no new information about the explosions, the morning meeting with Special Agent Carla Rosetti and her suspiciously quiet partner, Special Agent Demetri Meadows, was as unproductive as the ones I had with the cops. The big difference this time was that my mom and dad weren’t there. A lawyer named Harold Frolic was my counsel instead.

Frolic was a business attorney who helped my parents with any legal issues concerning their deli, Covington Kitchen. As delis go, it was an exceptionally profitable one, with a signature sandwich called the Oinker, which was a hoagie stuffed with different cuts and preparations of pig—prosciutto, pancetta, pork loin, and pork shoulder—and topped with Muenster cheese, pickles, and a garlicky sauce. The sauce was made from a secret recipe and my parents bottled and sold the stuff at local grocery stores under the name Oinker Oil. The plan was to go national with it someday and Frolic was helping them with that process. In the meantime, he was also helping me by saying, “You don’t have to answer that,” to every question Rosetti posed.

“But she should answer that,” Rosetti would invariably reply or, “It would help with the investigation. Doesn’t she want the investigation to succeed?” Her partner, Demetri Meadows, simply sat there, feet up on the table, staring me down, occasionally petting the graying stubble on his cheek like he was stroking a fucking cat.

Frolic was unflappable, though. The only thing he let me talk about was what I saw, which again, wasn’t much. Brian Chen popped. He was there, then gone. Then there was blood. Exactly like with Katelyn.

“You ever have beef with Brian Chen?” Rosetti asked me. “A reason to want him dead?”

Have beef. That’s funny. Who says that? Special Agent Carla Rosetti, that’s who. I wanted to answer, “I kissed him on a bus once and he pretended to be asleep instead of kissing me back. I was tempted to push him out the emergency exit, because that’s a messed-up way to treat a dame. So sure, I had beef, but that was a long, long time ago. I got over the beef.”

Frolic didn’t let me get a word out, though. “Don’t answer that,” he said for the millionth time. And then, “Are we done here?”

Meadows stroked his cheek as Rosetti shrugged and said, “Appears you two are.”

Frolic looked like he wanted to gather up a bunch of papers and stuff them in his suitcase before storming out of the station, but he didn’t have any papers or a suitcase. He took notes on an iPad and wore a shoulder bag. So there was a tense moment where we all just stood there. Until, of course, Rosetti stepped back from the table and, quite literally, showed us the door. I regretted not shaking her hand on the way out. I was sure of my innocence, but I liked her, so skipping the gesture of respect was kind of a dick move.

My parents met us in the parking lot and Frolic high-fived my dad like I imagine guys do at strip clubs. Then we divided up into two cars and caravanned to the Moonlight Diner, where Frolic ate a burger and blabbed on and on about my rights. I listened to maybe ten percent of what he said (Constitution this and permanent record that), because I spent most of the time with my phone in my lap, staring at that text from the night before.

Invigorating. Invigorating. Invigorating. What do you say to that? I considered a few responses.

Who’s this and how’d you get my number?

Invigorating how? Explain yourself, mystery texter!

I. Lurve. You.

What I finally settled on was:

Fuck you sicko.

About ten seconds later, there was a reply:

You don’t mean that.

Then the volley of texts began.

Me: Hmmm . . . so you can read minds?

Mystery texter: I know you feel things.

Me: Perv.

Mystery texter: Come on. You have a soul. You have ideas.

Me: Flattery will get you NOWHERE.

Mystery texter: I only want to talk to you.

Me: Then what?

Mystery texter: IDK.

Me: You a dude?

Mystery texter: More or less.

Me: You breathtakingly ugly?

Mystery texter: Not physically.

Me: OK. Here’s the dealio. You found my number. Now find my house. Ring the bell. Get past my parents. Prove you really want to talk to me.

If you don’t show up, then I won’t ever know who you are and shit won’t have to be awkward.

Up to the challenge?

Mystery texter: Challenge accepted.

“At least do us the courtesy of occasional eye contact as we discuss your future,” Dad said.

My eyes moved up from my lap, skipped his scowl, and moved on to Mom’s disappointed/sympathetic face. She mouthed, We fuckin’ love you. Which wasn’t weird because Mom swears a fair bit. Yeah, I know. Apples falling far from trees and all of that.

“I was checking the weather,” I said.

Dad motioned with his head to the window across from our booth. “Not a cloud in the sky.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m getting weird texts.”

Like everyone, I sometimes lie to my parents. I can never sustain it, though. I always end up telling them the truth. The more truth your parents know, the fewer things they suspect. No joke. If you’re a kid who constantly lies to your parents then, news flash, they know you lie and they probably think you’re a complete degenerate.

“Weird texts, as in threats?” Mom asked.

“No,” I said. “Some curious guy.”

Frolic took a bite of his burger and said, “Forward them all directly to me.” He used a voice that was supposed to sound wise and lawyerly, but considering he had a gob of ketchup on his cheek, it sounded a bit more like a skeevy old man asking a teenager to share her private correspondence with him.

“They’re not of the . . . legal variety,” I said.

“Almost anything can and will be exploited by the FBI if they count you as a suspect,” Frolic said.

“She’s not a suspect. She’s not a suspect.” Dad said it twice because he thinks if you say something twice, the more likely it is that it will be true.

“Well,” Frolic replied, “I’ll be seeing to it that the world knows and understands that soon enough. You have my word.”

I had to say it, so I said it. “And you have ketchup on your face.”

as you might have guessed

Mystery Texter didn’t show up at my house that day or the next. School was shuttered for the entire week, and all its homecoming festivities were put on hold, so the guy certainly had his opportunities to pop in. It’s not like he even had funerals to attend. The Chen family didn’t have the money that the Ogden family had and rumors were that they’d only be inviting close friends and family to Brian’s memorial service. Fine by me. More crying wasn’t going to help a thing.

The support group was canceled because Vince called it quits. He sent us all an email saying he would be pursuing other interests. Presumably, not hanging out with kids made of nitroglycerin. Who could blame him? My parents tried to book some immediate extra sessions with Linda for me, but she wasn’t returning their calls. Either she was throwing in the towel as well, or she was too busy fielding requests from new patients. It’s tough enough when one kid in your school blows up, even if you don’t really know her. When a second kid blows up . . . well, I don’t care if you’ve never even heard of him. You take it personally.

“Kids blow up now. And I’m a kid. Therapy please.”

Every news organization in the world had arrived. Perched on a gorge and overlooking town, the Hotel Covington’s parking lot was a hive of vans with giant retractable antennae. You couldn’t go anywhere without someone shoving a microphone in your face. On the other hand, you couldn’t stay home and zone out behind the TV or mess around on the internet because Covington High was all anyone could talk or write about. You couldn’t even watch things on mute, because people were making explosion gestures with their hands. This included newscasters, which is a bit unprofessional and undignified if you ask me.

To keep my mind off things, I spent a lot of time with Tess McNulty. She hated terms like “bestie” and “BFF,” but Tess and I were two people who knew how to best distract each other, so I think we qualified. We’d been inseparable since elementary school and, at the age of nine, had decided to grow old together.

We were spending a few weeks down the shore at my grandparents’ place after Tess’s dad took off on her and her mother. One evening, the two of us were riding our bikes past these gorgeous Victorian houses along the beachfront, and we spied two old ladies sitting in beach chairs at the edge of a porch. They were wearing kimonos, holding hands, and smoking a hookah while dipping their toes in the sand. Which was obviously adorable.

“Let’s be those old ladies, always and forever,” we pledged with the sunset as our witness.

Ten years later and the pledge remained intact. Only now we were getting around in cars. Since I never drove and she always did, Tess was the captain. And since she rarely partook in mind-altering substances and I often did, I was the wacky sidekick.

In the first few days following the demise of Brian Chen, we must have logged five hundred miles on her Civic. She had a playlist called Drive, Fucker, Drive!, which consisted mostly of songs with loads of swears. Hip-hop, obviously, but also some punk and even some country of the shit-kicking variety. We played it full blast with the windows down and drove west into the hills and farmlands near Pennsylvania, where the autumn colors were popping. We turned off the GPS and took roads we didn’t know.

This was something we’d done before, and almost always the plan was to get into adventures. Though our adventures usually consisted of getting dirty looks from old men as we pulled into rural gas stations. It’s illegal to pump your own gas in New Jersey, so Tess and I would sit in the car with the stereo still on, singing along to songs about being “higher than a motherfucker,” and the geezers would stand there shaking their heads and mumbling under their breaths until we drove off in a fit of giggles.

Of course, Tess was never higher than a motherfucker. She was responsible like that. Me, not so much. For instance, the Dalton twins had sold me some shrooms a few months before. At a farmer’s market, appropriately enough. I’d only taken them once, during a camping trip to the Poconos. They freaked me out at first, but then the experience mellowed and I eventually became “one with nature” and decided I was willing to give them another shot. I’d stashed them in the base of my bedside lamp and had been saving them for an outdoor concert or some event where my ermahgerd-your-voice-is-full-of-rainbows! shtick would be tolerated.

During one of our drives away from memories of Katelyn and Brian, swear-singing with Tess wasn’t helping me forget enough, so I insisted we stop by a Dunkin’ Donuts. I bought a steaming-hot pumpkin latte and I dropped a double dose of shrooms in it.

“You’re gonna make yourself sick,” Tess said.

“The opposite,” I said. “You brew them in liquid first to make sure you don’t get sick. That’s what Native Americans do.”

“In pumpkin lattes?”

“Well, they had pumpkins at least. Thanksgiving. Pumpkin pie. Duh.”

“Yeah. Duh.”

Tess was right. Twenty minutes later I was puking along the side of the road somewhere in the Pinelands. Tess rubbed my back and I imagined her hand was a bear’s paw—but not a scary bear’s paw, a cuddly bear’s paw, a cartoon bear’s paw—and it was at that moment I realized that shit was about to get loopy.

“Someone loves me,” I told her.

“I love you, baby,” Tess said.

“I know that, but I mean a phantom. Someone who lives in space between the spaces.”

“Jesus? Dumbledore?”

“Don’t joke, Tess. You haven’t got your real eyes on.” I meant this last part literally, because instead of her regular brown eyes, she had glimmering diamonds in her head.

“Let’s get you in the car. You can lie down in the back. I’ll play something acoustic. Something soothing.”

“Invigorating. Invigorating. Invigorating,” I said.

“Soothing,” Tess repeated in a voice that fit the word, and she guided me into the backseat.

“He reads my mind,” I said with a gasp. “Do you think he has especially big ears, like satellites that can read brain waves?”

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” Tess said.

As she pushed me on the chest and down into the seat, I handed her my phone, which was queued up to my texts. She took a second to read them and handed the phone back. “See. He loves me,” I said.

Tess leaned in and kissed me on the cheek and I felt little happy ants on my skin. “Well, whoever he is, he isn’t here. And I’m guessing he hasn’t shown up at your door yet.”

“Nope. He’s a chicken. Bock-bock-bock,” I clucked, and I wondered why people said chickens sounded like that because I wasn’t sure what they really sounded like, but I knew it wasn’t that. Definitely not that.

My feet were dangling outside, so Tess lifted and placed them on the seat and closed the door to keep them in place. It sounded like the air hatch on a rocket ship sealing shut. Noise, then silence. Then a few seconds later, noise again and Tess was at the controls, firing up the engine and launching us into space. Music burst from the stereo like bats from a cave and I felt every curve and bump of the road. I laughed hysterically as Tess sang along to some dopey song from the sixties or seventies about two friends and how one will always come running to help the other whenever the other calls out his name. Like a dog or something.

you’ve got a friend

Usually in these situations, we’d end up at Tess’s house. Her mom was a single mom and the thing about single moms is they tend to tolerate teenage shenanigans. I can’t remember how many times I’ve been drunk and draped over Tess’s shoulder as she led me upstairs while Paula peered over the top of whatever novel she was reading and remarked, “Hope it was worth it, Mara.”

That said, the other thing about single moms is they tend to date, and when that happens, they prefer not to have their seventeen-year-old daughter and her friend who’s swatting at imaginary dragonflies show up just as they’re pulling the cork from some chardonnay. On this particular night, Paula was on a date with a guy named Paul. It couldn’t possibly work out, for obvious reasons, but she’d asked if Tess could sleep at my house anyway.

This meant that Tess had to smuggle me past my parents. Not mission impossible, but not exactly easy. It was a good thing that Tess was charming and Mom and Dad liked her. They called her Tessy—which I guess she didn’t mind because she never objected—and they were always asking her about field hockey.

“Heard it was a close one, Tessy.”

“How do your playoff chances look, Tessy?”

“Flex your goddamn muscles, Tessy! Flex!”

Okay. Maybe not the last one, but they loved that she was an athlete, even though she wasn’t a star. Only started a few games that year. Didn’t score a single goal. Still, Mom and Dad were jocks in the days of yore and I never was, so Tess might as well have worked for ESPN. She was the one they always talked jock to.

Most of the time, it was annoying, but now it was essential. Tess had to distract them as I tiptoed up to my room. The shrooms were wearing off, but I couldn’t risk saying something embarrassing. And I couldn’t lie. I already told you about my problem with lying.

I know what you’re going to say. “Not telling equals lying!” Well, that’s just bad math.

Example: Say you pleasure yourself. Not that I’m saying you do . . . Actually, yes. I am saying you do because everyone does. But even if you’re the world’s most honest person, do you run downstairs after every sweaty session and holler, “Mom! Dad! Guess what?”

Of course not. Same thing with shrooms, though in this case it was pleasuring the mind. Okay, that’s going a bit too far, but I think you get the point.

As we pulled into the driveway, Tess gave me a pep talk. “All you have to do is make it to the stairs. You can do it, sweetie. I know you can. It’s seven o’clock, so they’ll be watching the news. I’ll pop my head into the family room, tell them that we grabbed some Dunkin on the road and now you’ve got a stomach thing—”

“Yeah, good. Dunkin. Stomach thing. That’s actually not a lie.”

“Right. And then they can ask me about when practice is going to start up again and you can slip into some jammies and into bed and if they want to come check on you, you can pretend to be asleep.”

“But I want to cuddle you.” This was partly the shrooms talking, but it was also the way we were. Neither of us had sisters, so we spent a lot of time doing what we thought sisters did. Braiding each other’s hair, cuddling, fighting. We hadn’t fought in a few weeks, but I knew a fight was coming. Maybe mid-cuddle, probably in the morning.

“Get your shit together, kiddo,” Tess was bound to tell me in her exasperated big-sister voice. And I would nod and she would scowl and we would both know that it doesn’t matter because I always end up doing the same shit all over again.

For now, in the driveway, we weren’t fighting. We were moving. “First things first,” Tess said as she grabbed my shoulders and pointed me to the door. “Upstairs. Eyes on the prize.”

“Aye-aye, cap’n,” I said, and strode up the brick walkway. Though I was still noticing so much—the rustle of leaves that sounded like rain, the glint of evening sunlight on the silver knocker that reminded me of a sword—I must not have noticed some obvious stuff, such as the skateboard resting against the oak tree in the front yard. I pushed open the door without knowing what I was really walking into.

Now, here’s something you’ve got to understand. No one ever hangs out in our living room. It’s strictly a Christmas-Eve-and- the-grandparents-are-visiting corner of the house. So when I stepped inside and saw three people sitting on the living room couch together, I was tempted to turn tail and not look back. Figured I’d stumbled into the neighbor’s place.

Dad’s voice cast an anchor, though. “Speak of the devil!” he hollered.

My head pivoted, and then my gaze landed on the person sitting between my parents. A boy. In a suit. On our living room couch. He stood, and I spoke. “And the devil doesn’t have a clue what the hell is going on.”

Mom rose to her feet next and she presented the boy like he was a car for sale. “It’s Dylan …”

“Hovemeyer, ma’am,” Dylan said as he pulled down on his jacket to straighten out the wrinkles. There were a lot of wrinkles.

Now it was Dad who stood and remarked, “Hovemeyer? I’ve seen that name in the old cemetery by St. Francis.”

“Our family goes back a ways,” Dylan said with a nod. “And people tend to die.”

I knew Dylan. Well, I didn’t know him personally, but everyone at school knew him. He was the one you suspected. Of what? Well, name it.

“Hey, it’s …” Tess had joined me in the doorway, her hand on my back.

“Dylan Hovemeyer,” he said, stepping toward us with a hand outstretched. I wasn’t sure which one of us the hand was intended for, but Tess was quicker on the draw. As she shook Dylan’s right hand, I presented my left one and soon I was shaking his left one. A pulse of energy zipped between the three of us, back and forth, like people doing the wave at a stadium. “We all have econ together,” he went on.

“Riiiight,” Tess and I said at the same time, as if this were something we’d never thought about before, which was total BS. We’d discussed Dylan. We had theories about him.

Mom’s face crinkled up as she said, “I assumed you were already friends.”

“We’re becoming friends,” Dylan said, staring at me. “Fast friends.”

The handshake à trois was still going strong and Tess gave me that what-now? look and I gave her that um-I’m-still-pretty-high look and so she took control, like always. She pulled her hand away and placed it on top of mine. It was the fuzzy hand again, the cuddly cartoon bear paw.

“You look great, Dylan,” Tess said. “And we’d love to catch up, talk econ and all that, but Mara is feeling crazy sick.”

I nodded, but I didn’t pull my hand away. I liked it, sandwiched up and tangled in their fingers. It was melting like grilled cheese.

“Vomit-all-over-the-place sick,” Tess added.

“Oh, honey,” Dad said.

“Pumpkin latte,” Tess informed him.

Mom’s eyes narrowed because she knew I downed those things like they were water during months that ended in BER. So I added a key detail. “Probably something fungal too.”

This made Mom cringe, but Dylan didn’t budge. The words vomit and fungal can usually scare away even the most dedicated panty-sniffer, but it required Tess’s field-hockey-honed arms to pry our fingers apart.

“Straight to bed for this one,” she said, pulling me toward the stairs. “Sorry, Dylan. Again, you look . . . dashing.”

Dylan seemed to take it in stride, shrugging as if he were called dashing all the time, which I knew for a fact he was not.

“Mara—” Mom started to say, but soon Tess and I were at the stairs and her tone shifted from surprise to embarrassment. “I’m so sorry, Dylan. She’s . . . well, she’s got a sensitive stomach.”

“That’s cool,” Dylan said. “I did what I came here to do.”

“And that is?” Dad’s voice was suddenly suspicious. He wasn’t an idiot. He could see through a wrinkled suit.

“I wanted to meet you two. And I wanted to shake Mara’s hand. Thank you for being nice to me. Your home is a nice home.”

By the time I reached my room, I had already heard the front door close. I looked out my window to the front lawn. Dylan was jogging across the grass, skateboard in hand. As soon as he reached the road, he tossed the board to the asphalt, hopped on, and escaped, suit and all, into the evening.

I opened the window so I could hear the squeaking wheels retreating into the distance as I collapsed on my bed. They sounded like sails being raised, a ship setting out to sea.

a trilogy

Before we dive back into things, I should probably tell you three stories about Dylan. Rumors, really, but rumors are as important as anything. Even if they’re not true, they end up turning people into who they are.

Story Number One: His dad died under a pile of shit.

I should elaborate, I suppose. Dylan started attending our school halfway through sixth grade. Middle school is a tough time for any kid, but being a new kid smack dab in the middle of middle school is about as tough as it gets. If you show up on the first day of classes, it’s not so bad. New teachers, new lockers. People are distracted. A few kids might say, “Hey, I don’t remember that guy,” but pretty soon you’re integrated into the pubescent stew. Yet another dude dishing out or dodging wedgies.

Show up after Christmas break and things are way different. Then kids are, like, “Hey, what’s this interloper’s deal. His mom move him to Jersey after his parents got a divorce? He get kicked out of his last school for sexting the nurse? This douche-nozzle ain’t one of us, that’s for sure.” Names are Googled, local news stories pop up, links are followed, until a tale emerges. The one for Dylan was that his dad died under a pile of shit.

I never looked it up to confirm, but I think Tracy Levy told me that Dylan was from some Podunk town in Pennsylvania and he lived on a farm with his parents and one morning his dad bought a bunch of manure (which is technically shit) and when the old man was unloading it—he hit the wrong button on the dump truck or whatever—it all came tumbling down on him and he suffocated beneath the pile. Dylan supposedly found him over an hour later and tried to dig him out with his bare hands, but it was too late.

Now, kids are cruel. We all know this. It’s no surprise that the story spread quick and thick. Thanks in no small part to people like me, who love some good gossip. But as cruel as kids are, they aren’t monsters. It wasn’t like they teased Dylan about it. It merely branded him with a reputation.

Dylan came from a farm, which meant he was poor. His father died doing something stupid, which, if you’re taking genetics into account, meant Dylan was stupid. On top of that, the stupid thing involved a pile of manure that Dylan pawed his way through, and now you’ve also got a kid who’s dirty. And stinky.

So almost immediately, Dylan was known as a dumb and smelly hick who was probably scarred for life by what he came upon one afternoon out there in Pennsyltucky. Everyone felt bad for him, but no one wanted to be his friend. Myself included.

Story Number Two: He burned down the QuickChek.

Again, this requires a bit of elaboration. At the intersection of Willoby and Monroe, there used to be a QuickChek convenience store. In the summer after seventh grade, Tess and I would ride there on our bikes and buy Mountain Dew, Twizzlers, and the latest issue of Vogue. We’d take it all down to a nearby creek, sit on the rocks, and use the Twizzlers as straws to drink the Mountain Dew while we’d tear pictures of models out of magazines and then fold them up into little paper boats that we’d race in the currents.

“Go Adriana! Go Svetlana! Go, go, go you glorious anorexic Romanians!”

Okay, fine. I’m fairly certainly we didn’t use the words glorious or anorexic or Romanian, but we got pretty damn excited about it. What else was there to do? We couldn’t drive. We didn’t drink, yet. Boys were an interest, of course, but they were all inside killing zombies or watching people kill zombies and Tess and I really weren’t that into zombies and …

Sorry. Zombies aren’t the point. QuickChek is. So it turns out that thirteen-year-old girls buying the occasional fashion mag, caffeinated soda, and bag of strawberry licorice isn’t enough to keep a convenience store in the black, and by the winter of that year it closed down. It was kind of a craphole to begin with, but once people stopped using the building, raccoons and teenagers took it over, sneaking in at night to do the things that raccoons and teenagers do, which is primarily making a big fucking mess.

Big fucking messes tend to be pretty flammable and so it was no surprise when some boys set the place on fire. Well, one boy set it on fire, if you were to believe the stories. No arrests were made, no parents found out, but the incoming freshman class entered Covington High convinced that on the last night of eighth grade, Dylan Hovemeyer had accompanied Joe Dalton and Keith Lutz to the abandoned QuickChek with the intention of smashing shit. You know, as a celebration of their manhood. Only Dylan brought an unexpected guest to the party: a Molotov cocktail made from an Arizona Iced Tea bottle filled with lighter fluid and wicked with the T-shirt we got for graduating from the middle school that said GO GET ’EM, YOUNG SCHOLARS.

Apparently, Young Scholar Hovemeyer got ’em and got ’em good. That is, if ’em was a stack of old newspapers that he pelted with the burning Molotov cocktail before Joe and Keith had any idea what was what. The three bolted out of there with flames licking their haunches and promised never to speak of the incident, a truce that lasted a full fifteen hours.

In the end, everything worked out for the best. The building’s owner probably got insurance money. The police never implicated the guys. And now there’s a Chick-fil-A on the lot and everybody loves Chick-fil-A. Except for the fact that they’re closed on Sundays. You can thank Jesus for that raw deal.

Story Number Three: Dylan is the father of three kids.

This was the least corroborated of the stories, but the other two stories certainly helped make it believable. Remember, by the time he was in high school, Dylan was known as a redneck pyromaniac with a dead father. In other words, he had nothing to lose, and so whenever something suspicious happened, he was a suspect.

A fire alarm pulled on the first day of finals? Gotta be that Dylan kid.

Laptops stolen from the computer lab? Paging Mr. Hovemeyer.

Spontaneously combusting students? You bet his name was whispered more than once.

But even before the spontaneous combustions, there was the curious case of Jane Rolling. Jane had always been a bit chubby. Not obese. Just consistently soft. Well, during junior year, she got softer and softer and softer still. Then one day, she stopped showing up to school.

“Triplets!” Tess told me a few weeks later.

“She was . . . with child? That whole time?” I said.

“With children. Yes. Three. All boys.”

“That’s boom-boom bonkers,” I said, because junior year was the year I said nonsense like “boom-boom bonkers.” Trying to land my own catchphrase, I will freely admit.

“What’s even more boom-boom bonkers,” Tess said in a mocking tone, “is the identity of the father.”

I shrugged because there was better gossip than Jane Rolling’s love life.

“How about Dylan?” Tess went on. “Manure-dad Dylan. Fire-starter Dylan.”

“Damn,” I said. “That’s right. They dated. Used to cuddle on the front steps before first bell. It was . . . nausealicious.” Yep, nausea-licious. Another junior year gem.

“So there you have it,” Tess said. “The delinquent has reproduced in triplicate.”

“Guy’s got powerful sperm.”

“I thought you passed bio. It’s more about Jane’s eggs. Girl’s got a chicken coop down there.”

“Well, I don’t envy either one of them,” I said, which wasn’t the whole truth. Having a trio of babies is not without its advantages. Once they learn to walk and talk, you can teach them song-and-dance routines and who doesn’t love a little soft shoe and three-part harmony?

Jane didn’t come back to school, of course, and Dylan became more of a lurking, mysterious presence than ever. I guess he talked to other kids. I guess he had friends. But to people like me and Tess, he was simply a bundle of rumors and suspicion, dressed up in jeans and ringer tees.

Literary Analysis: Dylan was sad. And dangerous. And fascinating.

back to the action

Monday was Halloween and school was back in session. The majority of kids and teachers skipped the getups entirely. I spotted a few “laser loafers” in the hall as a tribute to Brian, but that was the extent of the masquerading. Everyone was trying to pretend that things were back to normal, or at least the type of normal where you play football again.

All sports seasons had been put on pause after Brian, because obviously fit and limber kids need free time to grieve and freak out, the same as the rest of us sloths. Certain parents weren’t thrilled about the hiatus, though, and they had a point. Our teams were usually state ranked, playoffs were around the corner, and there were college scholarships at stake. Not for Tess, necessarily, but it was still a vital part of her high school experience. While I didn’t give a single shit about sports myself, I could at least appreciate that many of my peers depended on them for their health, sanity, and future.

The majority appreciated that too. After an open session of the PTA that Sunday, democracy declared Play Ball!, starting Friday with a football game against crosstown rivals, Bloomington. It was a rescheduled version of the previous week’s homecoming game, there were apparently “playoff implications,” and while there would be no dance and no parade with floats ferrying high school royalty, the stands would be full of current and former students and anyone who wanted to give a defiant finger to our predicament.

For most kids, football games weren’t ever about the football. These sporting events were excuses to hang out in the bleachers and catch up with friends, or lounge behind the bleachers in the softball fields, where blankets could be spread out and kids could watch the stars in the sky instead of the ones on the field. These brutal battles were distractions from our cloak-and-dagger variety of partying, where booze mixed with Gatorade was smuggled past lazy-eyed security guards. These rousing contests were perfect for covert kissing in the shadows and heart-to-hearts scored to the sounds of cheering parents and girlfriends.

The homecoming game was going to be my first date with Dylan. It was his idea and the arrangements were made by text, since there wasn’t much time in econ to discuss such things. As the week chugged along, the three stories and their subplots fizzled in my head and mixed with the dizzying memory of his hand on my hand. I know, I know. Getting all worked up by a little handholding? Total middle school. Elementary school, even. But when you think about it, hand-holding can be really sexy, especially when you’re holding the hand of someone who may or may not be any number of things.

Was I leery of Dylan? Obviously. Was I excited about seeing him again? Uh . . . yeah. During lunch on Wednesday, Tess made me promise to be careful. “If he’s half the things we think he is,” she said, “I’m not sure you want to be alone with him.”

“That’s why the football game is perfect,” I said. “Plenty of people around, but no one listening in on us.”

“I wish I didn’t have practice that night. I want to watch over you.”

“That’s sweet. But that’s also creepy. I’ll be fine. What are you worried about? That he’ll fill me with quadruplets during halftime or that he’ll douse me in gasoline to celebrate every touchdown?”

Tess took a potato chip from my bag and poked me playfully on the nose with it. “Do you really want to get close to someone who has three kids? Plus all the other stuff? Do you want to have a look inside all his baggage?”

I snatched the chip from Tess’s hand, stuffed it in my mouth, and as I chewed, I said, “I’ve got plenty of baggage myself.”

“A carry-on at best. This guy would have to pay hundreds of dollars to check his.”

“Is Walsh doing a unit on metaphors in AP English or something? Because I don’t think you get extra credit for using such pathetic ones, especially outside of class.”

“I should poison your drink,” Tess said with a fake sneer as she watched me take a slug from my strawberry smoothie.

“Should, but never would,” I said as I wiped my mouth. “You know why?”

“Why?”

“Because you would be sad. You would feel . . . All. The. Feels.”

Tess raised a finger. “How dare you? You know how I hate those words.”

“You won’t hate those words when they’re on the cover of my novel, the blockbusting award-winner that I dedicate To My Darling Tessy.”

“Royalties,” she said as she patted me on the cheek. “Dedications are sweet, but cutting me in on the profits would be a whole lot better.”

“Fine,” I replied. “I’ll be your sugar mama until the end of days. I’ll keep your toes dipped in sand and your body draped in silk.”

She put out a hand out and I shook it. The deal was officially sealed.

fun and games

Front row center.

Or so said the text from Dylan that arrived Friday afternoon. I got a ride to the game with the Dalton twins because Dylan hadn’t offered one. I figured there wasn’t enough room on his skateboard.

The Daltons shared a red RAV4 bought with money they made bussing tables at Covington Club, the restaurant at our local golf course. At least that’s where they told their parents they got the cash. In reality, the majority of their income was the redirected allowances of kids who partook in illegal plants and pills. Kids like the late great Katelyn Ogden. Like me.

Joe Dalton was older than Jenna Dalton by a few minutes, but he was definitely the younger at heart. And mind. Since he was supposedly one of the guys with Dylan the night the QuickChek burned down, I could have asked him if the whole Molotov cocktail thing was true, but I wasn’t sure I wanted the answer to spoil my evening. So instead I sat quietly in the back, while he drove and argued with Jenna about whether it would be better to retire to Florida or Buenos Aires.

Joe was advocating, poorly, in favor of Florida. “Bikinis, bottle service, and alligators, Jenna! Doesn’t get any better!”

Jenna, on the other hand, was selling Buenos Aires like a real estate agent, highlighting “the mild climate, the European flavor, the dancing till dawn, and the steaks as big as laptops.”

After a while, they seemed to forget I was there and were trading inside insults, which are like inside jokes but even worse because as Joe hollered, “You’re such an Aunt Jessica!” and Jenna yelled, “Go puke on Donald Duck again,” I had no idea who was winning. It was getting unbearably loud and so I started fanta-sizing about the two of them screaming themselves to death and leaving me all their drug money so I could hop on the back of Dylan’s skateboard and the two of us could catch the next plane to Argentina where we’d forge a new life full of red. Red wine. Red meat. Red-hot love.

When we reached the lot for the football field, I slipped out with a “mucho appreciation, amigos,” and hightailed it to the bleachers. The fight song was pumping and the seats were as full as I’d ever seen them, but sure enough, there was Dylan in the front row with a bag of popcorn next to him, saving me a seat.

“Here I am,” I said, and sucked in a deep breath. I was not in shape. I had never been in shape.

He pulled the popcorn to his lap, revealing a buttery stretch of aluminum for me to sit on. “And there you go,” he said, but he failed to wipe any of the sludge away. It didn’t bother me, necessarily, though it did leave me with a decision. I didn’t see any napkins, and I didn’t want to be a pain in the ass from the get-go and ask him to fetch me some. I especially didn’t want to call him out for being either clueless or inconsiderate. So I was left with a choice between having a buttery hand or a buttery butt.

Protip: Always avoid the buttery butt.

And that’s what I did. I ran a hand across the seat a couple of times while Dylan was watching the referee flip a coin. As I sat, I flicked the butter down into the chasm beneath the bleachers. “What the, what the—?” muttered some poor dope who must’ve been beneath me, but that was all I heard because the crowd went absolutely apeshit when our team won the coin toss. The coin toss. It was going to be that kind of game.

“So,” I said once the cheering petered out. “You prefer the bleachers to, I don’t know, somewhere we don’t have to actually watch the game?”

“I’m looking forward to the game,” he said without even a hint of sarcasm.

“You are?”

“Sure. I’ve been a fan of the Quakers since I was a kid.”

Yes, you heard that right. We are the tenacious, the proud, the fearsome . . . Quakers! It goes back over three hundred years to when this area consisted of a few scattered communities of Quakers who didn’t make it as far as Pennsylvania. The lazy Quakers, if you will. We’re a public school now, without any religious or philosophical affiliations, except for a mascot who basically looks like the guy from the oatmeal box, except with a Quakerly sneer in place of a Quakerly smile.

“So always a Quakers fan, huh?” I said, because I didn’t know what else to say to something like that. And then it dawned on me. “But wait, didn’t you move here during sixth grade?”

“I’ve always been here,” he said. “Sixth grade was when I started taking classes. I was homeschooled until then.”

“Oh. That’s news to me.”

“News to most people,” he replied, and as he spoke, he kept his eyes on the Bloomington players preparing to kick off, sizing them up like my grandpa used to size up horses at the track. “My dad died of a stroke that year. Out in a field while laying down some fertilizer. He was a dairy farmer, but he also helped my mom teach me. Once he was gone, it was too much for Mom to do alone, so I was transferred to the general population.”

He put his hands out and motioned to the crowd, which leapt from the bleachers as Jalen Howard caught the opening kick and returned it to the forty-yard line.

“That must have been tough,” I hollered over the noise.

Dylan shrugged. “Another Hovemeyer for your dad’s favorite graveyard.”

It was a callback to the night at my house. And it was funny. Not because Dylan’s dad was dead and buried, but because my dad is definitely the type of guy who would have a favorite graveyard. After all, he has a favorite public restroom (Covington Town Library, second floor), a favorite fire hydrant (the shiny blue one on Gleason Street), and a favorite park bench (the warped beauty in Sutter Park he calls Ol’ Lucy).

So I laughed. And Dylan smiled.

“I never pegged you for a football fan,” I said.

“Drama,” he said. “There’s always a different story. I like drama. I like stories.”

Our quarterback, Clint Jessup, threw an errant pass that went into the bleachers and the crowd let out a collective sigh. “What’s the story this time?” I asked.

“Depends on your religion.”

“Meaning?”

He turned to me and his beaming face opened him up like a sunrise opens up a landscape. “This is a resurrection story. We’re back.”

the thing about comebacks

We were back. Our team had gone into the game as underdogs. Bloomington was a perennial powerhouse and we’d missed far too many practices to realistically compete. But compete we did. Leads were exchanged, and new numbers were constantly lighting up the scoreboard.

There was a certain amount of excitement and it was fascinating to see Dylan glued to every pass and tackle, but it confirmed to me that no matter how much drama there was, I still didn’t care about sports.

What I did care about, however, was Harper Wie, Perry Love, and Steve Cox. They were players on our team. Benchwarmers, basically. Which was important. More than any touchdown, I wanted to see the three of them sit next to each other on the bench.

Why ever would you want to see something so mundane, you ask? Well, it goes back to junior year. In general, I don’t have a problem with football players. At Covington High, they’re mostly nice guys. They don’t beat up people in the bathrooms. They don’t cheat their way through classes (as far as I know). They don’t record their dalliances with cheerleaders and post them on RaRa-Bang.com or whatever the amateur porn site du jour is called. Sure, they’re not saints, but they’re usually too busy being football players to be much of anything else. Harper Wie, Perry Love, and Steve Cox were the exception. Or at least they were for a brief moment, and sometimes all it takes is a brief moment.

It was a Friday last fall and they were wearing their jerseys, as is the custom on game days. They were sitting together in the cafeteria when I walked by them and I heard Perry say, “Oh, what a glorious fag he was, the faggiest fag in all the land, and his fagginess will be missed, the fag.”

Or something to that effect, give or take a fag or two.

It made the two other guys burst out in laughter and made me immediately want to wring their necks. It wasn’t really Perry’s choice of words, which were more or less baby shit—gross, but juvenile and inconsequential. It was the target of his slurs. It had to be Mr. Prescott, our art teacher. He had passed away the week before and the school newspaper was planning to run an obituary. Perry was the editor and I had it on good authority (the authority being Tess, who worked on the paper too) that Mr. Prescott was gay. Not closeted, but not exactly advertising his lifestyle. The staff had been discussing whether to include this fact in his obituary. He was survived, they’d learned, by a partner named Bill. The two had been together for years, but they didn’t bother to get married, even when they were legally allowed. Maybe they didn’t care about marriage. I don’t know.

Now, the death of Mr. Prescott was undoubtedly sad. But he was old. In his eighties, I think. Retirement was like marriage for him, I suppose. Never in the cards. Being an art teacher is a pretty mellow gig, after all. And it wasn’t like he was my mentor or even my favorite teacher. But still, there’s something about young men making fun of old men that really gets to me.

Go ahead and make fun of people your parents’ age. Make fun of your peers. Make fun of babies, even. Old people, though? Completely off-limits. And recently dead old people? Please. Why would I even have to explain how fucked up that is? Which— flashing forward to my football date with Dylan—is why I wanted to see them lined up together on the bench. Harper Wie, Perry Love, and Steve Cox, in that exact order.

Still don’t get it? Let me explain.

Football players have their last names sewn on the backs of their jerseys, and it may not be the world’s perfect pun, but when you get Wie (pronounced We), Love, and Cox lined up and you snap a pic and post that shit on Instagram . . . well, it isn’t exactly justice for them being a triumvirate of homophobic, ageist pubes, but there’s a certain poetry to it. At least that’s what I was telling myself.

So there we were, Dylan and I on a date—him watching football and me watching the bench. My phone was set to camera and resting on my thigh like I was a regular gunslinger. I couldn’t settle for Wie Cox, which actually happened a couple of times. Because while that might have played well in Scotland, I needed the bingo, especially since Perry Love was the ringleader of the bunch.

During the moments my eyes weren’t poised on the bench, they were resting on Dylan. For most of the game, he was calm, studying the action and—when there wasn’t any action, which was most of the time—studying the coaches or the huddles. He seemed to be analytical about it all at first, subtly shaking or nodding his head as he dissected decisions. But as the game went on, and the crowd got more riled up, something changed in Dylan. He didn’t become the frothing-at-the-mouth chest-painter I imagined most rabid sports fan to be. He became something much more charming.

He became a kid. Whenever our team made a big play, he’d lean forward in his seat, gripping the edge like gravity was going to give out at any moment. Whenever Bloomington snatched back the advantage, he’d clench his teeth and rap the seats with his knuckles and send little tremors through my thighs. And in the fourth quarter, whenever things got particularly tense, he’d reach over and grab my hand, and shake it gently.

There had been chatting during the game. I had asked questions about what was happening and he had explained (in what were supposedly layman’s terms) about formations and strategies, though I don’t remember even a word of it. What I do remember was his tone. It wasn’t condescending. It wasn’t “let me explain some man stuff to this precious little doll.” Again, he was a kid. He was excited and proud. He might as well have been talking about his Legos.

So every time he grabbed my hand, I was holding a kid’s hand and it was cute and innocent and it wasn’t at all like holding Dylan’s hand in my living room a few days before. The gentle shakes were the ones I recognized from my youngest cousins, the can-you-believe-that-we’re-at-a-water-park-and-there-are- waterslides-and-oh-boy-I-could-pee-my-pants-right-this-minute! variety of shakes.

Kids grow up, though, and the kid version of Dylan went through puberty in the final seconds of the game. The scoreboard read Bloomington 38 and Covington 33. We had the ball at the fifty-yard line. Twenty seconds left on the clock. I’d seen enough movies to know that this was why people loved sports. Underdogs making good and last-second scores. Everyone on our team was wearing two black armbands, for chrissakes. Emotion to spare, my friends. To spare.

And Bloomington wasn’t taking it easy on us out of sympathy. They were snarling, punching, and gouging. “It’s a sign of respect,” Dylan explained. “No true athlete wants to be a charity case. This is the way it should be.”

The crowd was singing the alma mater, which pretty much never happens because it’s a creepy bit of propaganda about “merging together as one, for the honor of mighty Covington.” Still, in this context, it was appropriate. We had suffered together and together we were fighting through it, one throbbing mass of cheers and tears. We didn’t need to win this game necessarily, but we needed people to remember this game. Even a girl who doesn’t care about sports can be on board with that.

Our quarterback, Clint Jessup, was doing a hell of a job, but with twenty seconds left on the clock, he buckled over and started puking on the field. I’m not sure if there are rules about such things, but I think that even in football, puking puts you on the sidelines for a play or two. Because that’s exactly where Clint headed. Helmet on the ground, head in his hands, he stumbled to the bench.

“They don’t have any timeouts left, so they gotta go with Deely,” Dylan said with a groan. “Deely has never even taken a varsity snap.”

Deely was Malik Deely. From pre-calc. And support group. The one cool head in our woeful bunch. He was the team’s backup quarterback, which, from what I could gather, meant he stood around holding a clipboard all game until the last twenty seconds when he was expected to come in and save the day because our number one guy was too vomity.

“Don’t worry, Malik can handle pressure,” I assured Dylan and Dylan gave me a you-better-be-right look, and it was that exact moment that he changed, that the hand-holding changed, that the charming became charged. He squeezed my fingers—a little too hard at first perhaps—but when he eased up, he soothed things by stroking them. He ran a fingertip over my palm, almost as though he were writing a message on it.

Maybe it was the crowd pulsing around us or the sweaty anxiety all over the field, but it was an unbearably sexy moment, at least for me. And when Malik Deely lined up behind his teammates and started barking out the play, I was basically at a point where I wanted to pull Dylan in and stuff my face in his neck and nuzzle, nuzzle, nuzzle. Weird, I know, and may not seem all that hot to you, but when you want something at a certain moment and you’re not sure whether you can have it, but you know that it’s within the realm of possibility if only you have the courage to go after it . . . well, I don’t care who you are or what that thing you want is, the simple fact is this: It’s fucking hot.

Problem this time was that I didn’t go after it. It didn’t seem right to distract Dylan. Because as Dylan ran that fingertip over my palm, and I thought about scorched convenience stores and dancing triplets and infinite nuzzling, Malik Deely took his first varsity snap.

I’m not exactly a sportscaster, so I’m not sure the best way to describe what happened next, but here goes.

Malik had the ball, raised up like he was ready to pass, and he moved left and right, looking downfield to see if there was anyone open. Two of the defenders from Bloomington pushed past the guys who were supposed to be blocking them and they closed in on Malik.

“Jarowski!” Dylan yelled, as did almost everyone else in the crowd, because the lumbering lunk named Jared Jarowski had broken free. But it was too late. The defenders were pouncing on Malik and Malik was bringing the ball to his chest and curling into a fetal position.

A collective gasp. And then . . . a collective cheer. Somehow, Malik slid out from under the two defenders without being tackled and there was an open patch of grass in front of him.

“Go! Go! Go!” Dylan hollered, tapping my hand with each go!

Malik went. He burst forth with the ball tucked under his arm. He reached the forty-yard line, then the thirty-five, then the thirty.

Defenders pursued. Malik spun out of danger and kept running. He stuck an arm out and knocked a guy over. He hurdled another guy. He was at the twenty-five, then the twenty.

I’ll admit it. Football wasn’t entirely boring. I could see the clock was in the single digits. I was as wrapped up in it as anyone else. A few of the guys on our team made some amazing blocks, throwing their bodies in front of Bloomington players who were nipping at Malik’s heels.

“Please no flags, please no flags, please no flags,” Dylan chanted as Malik hit the fifteen and then the ten.

It was almost too good to be true. A touchdown would win it for us. We didn’t even need to make the extra point. Get the ball into the end zone, spike the thing, dance a dance, and call it a day. But when Malik reached the five-yard line, it happened.

He dropped the ball.

The crowd howled. The ball bounced once. Almost everyone within a five-yard radius dove for it. Malik didn’t need to dive though, because on the ball’s second bounce, he caught it. A shuffle, two leaps, a dive, and he was in.

Touchdown!

Nuts is not the word for what the crowd went. Psychotic is more like it. The stands shook as Quaker fans threw themselves on each other, over each other, and into the field. The band tried to break into the fight song, but the pandemonium sent their trumpets and tubas flying and the only sound they made was the clang of brass on bleachers.