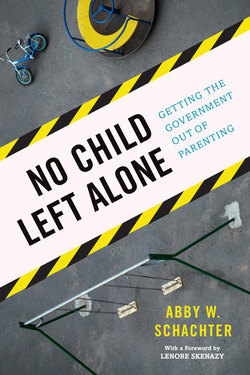

Читать книгу No Child Left Alone - Abby W. Schachter - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

CAPTAIN MOMMY \′kap-tn ′mäm-ee\ n. idiom Mother who encounters and resists the excessive intrusion into family life, most often through the use of overly expansive definitions of the state’s role in protecting children. Example: Lenore Skenazy, founder of the Free-Range Kids movement, is the first Captain Mommy.

CAPTAIN DADDY \′kap-tn ′däd-ee\ n. idiom Male version of a Captain Mommy.

“I’D LIKE TO LET my kids walk to school, but . . .”

But what?

You’re the parent! They’re your kids! You want to give them the freedom you loved—to walk, explore, stay home, go out, or even, once in a while, to get lost or goof up. To do things on their own.

But . . .

As Captain Mommy knows all too well, it’s no longer straightforward.

For the first five years after I founded the Free-Range Kids movement, parents who wanted to let their kids walk to school would end that sentence with, “but I don’t want them to get kidnapped.” Fair enough . . . even though the chances of that happening are so outlandishly small, that if for some reason you actually WANTED your child to be kidnapped by a stranger, do you know how long you’d have to keep him outside, unsupervised, for that to be statistically likely to happen?

About 750,000 years. (And after the first 100,000, you really couldn’t even call him a “kid” anymore.) But that’s for another book.

Suffice it to say that a few years ago, the “I’d like my kids to walk” sentence started ending differently: “. . . but I don’t want to get arrested.”

Fear of predators had been supplanted by fear of the police.

The stories, after all, were in the news: “I let my nine-year-old play in the park and was thrown in jail for negligence.” “I let my kids eleven, nine, and five play in the playground across the street from me, and I was put on the state’s child-abuse registry.” “I let my two-year-old wait in the car while I ran in to get her life jacket and was charged with child endangerment. And yes, I get the irony.”

Real stories.

The problem seemed to be twofold. First, the government is made up of human beings. Humans who watch TV, read Facebook, hear about childhood crimes and tragedies, and end up just as outraged as the rest of us. Problem Number Two is this: They feel that they can prevent all these sad tales from ever happening again if only they passed some more laws.

So they do. And now in 19 states, you can’t let your kid wait in the car while you go run a short errand. In British Columbia, the Supreme Court ruled that it is illegal to let your child stay home alone as a “latchkey kid” until age 10, because—the judge mused—what if the house caught on fire? In Rhode Island, four legislators proposed a law that would make it a crime to let any child below 7th grade—age 12!—off the school bus in the afternoon unless there was an adult waiting to walk the kid home.

That law was, mercifully, shelved, thanks to reality seeping in: Do we really think an 11-year-old can’t walk a block home by herself? Do we really want parents quitting their jobs to stand out at the school bus stop every afternoon at three? While we’re at it, do we really have to think in terms of the least likely, most horrific possibility—a carjacking! a house fire! a kidnapping!—every time we make any decision regarding what parents and kids should legally be allowed to do? If so, wouldn’t that mean criminalizing any parent who drives her kid to the mall? After all, car rides can be deadly, too. Where does the obsession with safety stop?

That’s the overarching question our good Captain addresses here, and the one we all have to consider unless we want to pursue absolute safety, which requires constant surveillance, unfettered intervention, and a farewell to freedom for parents and for kids.

Which doesn’t sound so great when you put it that way.

So start the charge, Captain. It’s time for a revolution.

—LENORE SKENAZY,

founder of the book, blog, and movement Free-Range Kids