Читать книгу Night and Day - Abdulhamid Sulaymon o’g’li Cho’lpon - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

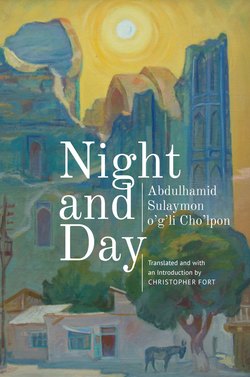

ОглавлениеAn Introduction to Cho’lpon and his Night and Day

Abdulhamid Sulaymon o’g’li Cho’lpon (1897–1938) is best known as the most outstanding Uzbek poet of the twentieth century. When he emerged on the literary scene in the years following the Russian February Revolution of 1917, he became a leading voice for the new Turkic lyric that came to dominate Uzbek poetry in the 1920s. He developed a reputation for an elegiac style punctuated with colorful imagery and an innovative use of traditional symbols and metaphors. In the late 1920s, as Bolshevik-trained Uzbek intellectuals took over the literary sphere in Uzbekistan, Cho’lpon’s poetic fame transformed into notoriety. He became a political pariah, the subject of constant attacks in the press. In 1934, attempting to reconcile with Soviet power, he submitted the present novel, the first book of a planned dilogy Night and Day, to a Soviet literary contest. Three years later, Cho’lpon was arrested by the NKVD (the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs—Stalin’s secret police) as part of Stalin’s Great Terror (1936–1938). The work translated here, Night, was pulled from the shelves and banned; the sequel, if it existed, was likely destroyed by the NKVD. Night circulated in Uzbekistan in secret, influencing new generations of Uzbek litterateurs. Only with glasnost was the novel republished. It now stands as an exceptional piece of Uzbek prose. In the minds of Uzbek readers, Night tends to be overshadowed in the canon by the first Uzbek novel, Abdulla Qodiriy’s Bygone Days (O’tkan kunlar, 1922), but Cho’lpon’s chef d’oeuvre is arguably the superior work.

In post-Soviet Uzbekistan, Cho’lpon is perhaps equally well-known as a so-called “national caretaker” (millatparvar). In the second decade of the twentieth century, Cho’lpon and like-minded reformers, often called jadids, embraced a reformist discourse that involved, among other dimensions, an interest in European technology and the idea of the nation alongside traditional Islamic critiques of societal decline. The jadids implored their fellow urban Turkestanis to awaken themselves to the dangers of Russian colonialism and restore the lost glory of their people. Despite what modern Uzbek critics and Cold War-era Western researchers assert, these reformers’ main rhetorical and political opponent was not Russian imperialists but the religious elite, the ʿulama, whom the jadids felt impeded their nation’s progress towards modernity. For jadids, the Russian conquest of Turkestan was a result but not the cause of the decline of Islamic civilization.1 At the end of the present volume as Cho’lpon’s character Razzoq-sufi, so named for his duty to perform the call to prayer,2 loses his grip on reality, the voices around him poignantly ask, “who is crazy? The Russians or us?” These rhetorical questions direct the reader to first seek fault for the novel’s tragedies in Turkestani backwardness. Naturally, educated reformers like Cho’lpon presented themselves as the people best suited to lead Central Asia in the twentieth century, a strategy which brought them into direct competition with the ʿulama for the ears of ordinary people. Russian colonial administrators, for their part, bridled jadid ambitions, consistently siding with the ʿulama in all disputes to maintain their rule over Central Asian society.

The Russian revolutions of 1917, February and October, profoundly transformed the jadids and Cho’lpon. Whereas the Russian imperial state supported the traditional religious class, Lenin and the Bolsheviks found temporary allies in jadids. The Bolsheviks never trusted their native partners completely, knowing they were not Marxists. Nevertheless, the communists temporarily granted jadids the state tools to enact a jadid vision of modernity. As their power grew, jadid ideas and philosophies transformed dramatically. The Turkestani Muslim nation they intended to revive before the revolution became a specifically Turkic nation.3 Before 1917, jadids wrote in both the local Turkic tongue and in Persian, often mixing the two languages. Soon after October, under the influence of Ottoman modernizers and Turkic reformists of the Russian Empire, jadids began to see Turkic culture as more suited to modernity than Persian. Cho’lpon, one of the more active proponents of this view, introduced new Turkic meters and Turkified the lexicon of local poetry. By 1924, when Stalin ordered the national delimitation of Central Asia, splitting the territory into the contemporary five republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), jadids had come to a consensus on the Turkic nature of their nation, calling the culture Uzbek, a name with Turkic origins, and the territory—Uzbekistan.

After the revolution, women’s liberation became another critical part of the jadid program and one of Cho’lpon’s main concerns. Jadids, like modernizing intellectuals in many other neighboring Muslim societies such as Turkey and Iran, were influenced by European concepts of sexual morality and domesticity and began to agitate for their society to adopt them. They championed monogamous marriages based on romantic love and in turn attacked polygamy, pedophilia, homoeroticism, prostitution, and adultery. While the jadids may have exaggerated the prevalence of these phenomena in their society, they were no doubt as in evidence here as in any other society. The jadid solution was to open women up to the world, to release them from the confines of their “four walls” (a common metaphor for women’s internment in the home), and put them on more, though not completely, equal footing with men. Cho’lpon’s 1920s elegies and later his prose in the novel therefore often take readers inside local women’s sequestered lives, invading, with the reader, the intimacy of their homosociality in order to eliminate it. As a narrator, he mourns women’s innocence and failure to recognize their own imprisonment.

As several scholars have noted, the jadid vision for women’s liberation was far more limited than that of the Bolsheviks.4 In their literary portrayals, Cho’lpon and his fellow reformers rarely acknowledged women’s agency.5 Cho’lpon’s narrator often bewails Uzbek women’s captivity but simultaneously relies on it for protection of the “innocent” femininity he feels is crucial to the preservation of Uzbek cultural heritage. Like many other reformers in the Islamic world at this time, Cho’lpon saw women as mothers of the nation whom it was men’s duty to protect, thus his advocacy of women’s liberation was often at odds with his advocacy of the nation. At yet another level, Cho’lpon entraps his female characters: he fetishizes women’s misunderstanding of their environment, transforming their ignorance into an aesthetic.

Cho’lpon’s novel, as I will show in the analysis to follow, is full of the ignorance and indecisiveness that characterizes his poetry, setting it apart from many of the prevailing literary trends in the Soviet Union. Writing his novel in the early 1930s before Socialist Realism, the official literary method of the Soviet Union, had been canonized and defined, Cho’lpon proceeded along a different path. His characters do not come to the class consciousness that would be demanded by Stalinist critics in the late 1930s; rather they are “unconscious” in their indecisiveness, ignorance, and constant doubt. They misunderstand, misrecognize, and commit mistakes, always receiving epiphanies that are endlessly redacted. His characters are, in a word, incomplete beings, always deferring final judgment to another time, matching, perhaps only by a convenient coincidence, the incomplete form of the dilogy Night and Day (Kecha va kunduz). I use these characters and the structure of the novel to argue that Cho’lpon was himself undecided in his relationship to the Soviet Union, incomplete, like his novel, in his convictions, and thus always available for reinterpretation by future readers.

By bringing out the ambiguity in Cho’lpon’s text and his biography, I intend to challenge the uncritical reception of jadids in post-Soviet Uzbekistan. Since Uzbekistan gained its independence in 1991, its intellectuals have done little in the way of rethinking the legacy of jadids and the larger Soviet system itself. Instead, they have largely inverted the Soviet historical narrative. Whereas the Soviet narrative held that the October Revolution freed Uzbeks from tsarist colonial oppression, gave birth to Uzbekistan, and guided its national culture to modernity, the post-Soviet narrative explicitly asserts Uzbeks’ transhistorical victimization under Russian imperial and Soviet rule. According to this account, the Russian Empire and the Soviets alike stalled Uzbek development and repressed Uzbek native culture in favor of Russian culture. Cho’lpon plays a major role in both narratives: he was reviled in the Soviet Union from the late 1920s up to glasnost as an enemy of the people, but now he is unequivocally celebrated as a national hero. Both narratives lack nuance and rely more on teleology than facts. They each attribute complete conviction to their actors, effacing the ambiguity intrinsic to any indeterminate future. An examination of ignorance in Cho’lpon’s characters helps us grasp the author’s own inconclusive musings on the Soviet state, which consequently permits a more dynamic and exciting engagement with Uzbek literature and history.

Here I offer a biographical sketch of Cho’lpon’s life and times, the history of the novel, and an analysis of its contents. Cho’lpon left no diary or other material giving an account of his life, and thus any biography of him is nothing more than a sketch that relies on the self-censored testimonies of relatives and memoirs of friends. I fill in the gaps in the biographical record by introducing the reader to the historical context of Cho’lpon’s life and his poetic oeuvre. For these same reasons, we know little about the process of writing the novel. Cho’lpon left no authorial explanations about his intentions with the work and the sequel that he is rumored to have written. I therefore make abundant use of historical and literary context to form an argument about the author’s goals with Night and Day.

CHO’LPON’S LIFE AND TIMES

Abdulhamid Sulaymon o’g’li, better known by his penname Cho’lpon, was born in 1897 in Andijan, a city in the Ferghana valley of modern-day Uzbekistan. The Russian Empire had annexed the city with its conquest of the Kokand Khanate in 1876, incorporating it into the colonial administrative unit of Turkestan. Cho’lpon’s life spanned Russian colonialism, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the Stalinist purges. His views and literary oeuvre were inevitably affected by his confrontation with both the racial and religious hierarchy of empire and revolutionary calls for radical equality.

As in other European colonies with majority-Muslim populations, Russian colonial administrators in nineteenth-century Turkestan ruled from a distance. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, most Europeans believed that Islam was in its death throes as a religion. Muslims would soon see the superiority of Christian peoples and abandon their faith. Imperial rulers needed only to not provoke their colonized subjects, lest a sudden burst of fanatic revolt breathe new life into the dying creed. Therefore, Russians minimized the so-called “civilizing mission” that justified their colonial conquest in the first place. They banned Christian proselytization, left Islamic law intact, and isolated themselves in Russian quarters of major cities such as Samarqand and the Russian regional capital, Tashkent.6

Annexation into the Russian Empire greatly increased the fortunes of Cho’lpon’s merchant father, Sulaymon mullah Muhammad Yunus o’g’li. While the Romanov Empire left many aspects of Central Asian life untouched, commerce changed dramatically. With new trade routes and modes of transportation, Sulaymon expanded his textile trade routes as far north as Orenburg.7

Russia’s imperial presence changed Sulaymon’s social and cultural outlook as well. Sulaymon was well versed in Islamicate high culture. He participated in poetry gatherings with learned men, mullahs and eshons, and even compiled his own divan (poetry collection), under the penname Rasvo, meaning “base” or “foul,” a sign of humility before God. In educating his eldest child, Cho’lpon, he proceeded in the fashion traditional for precolonial Central Asia and much of the premodern Islamic world. His father sent him to a madrasa, a secondary school where select students train to become Islamic learned men. There, Cho’lpon learned Arabic and Persian, and was initiated into the world of Islamicate high culture.8 However, Sulaymon soon reconsidered his son’s future prospects and enrolled Cho’lpon in a Russian school. Colonial administrators, beginning in the mid-1880s, established so-called “Russo-native” schools, which taught Russian and local native languages to Central Asians. The goal of these schools was to create a class of native intermediaries to administer colonial rule in Turkestan.9 In this school, Cho’lpon learned the basics of the Russian language, arithmetic, geography. He also received some of the native instruction typical of the maktab, a primary school in Central Asia, and the madrasa.

Cho’lpon’s education at a Russian school was rare for his time. Most Turkestani parents did not trust the Russian schools, and enrollment was always low. Russian imperial administrators could often resort to drastic measures. Notably, they sometimes forcibly enrolled children from poorer members of the community in order to fill classrooms.10

In the late 1890s, yet another type of school, associated with a movement of progressive Muslim reformers, was introduced in Central Asia.11 Jadids, named for the pedagogical method they advocated in these new schools, usul-i jadid (new method), promoted a novel means of learning the Arabic alphabet in which the local tongue, called Turki or Chagatai, was written. While traditional maktabs taught the alphabet via the syllabic method whereby students memorized syllabic combinations of letters, jadid new-method schools trained students with a phonetic method, teaching them the sounds that each of the letters represented. As a result, jadid-school students could read new, unfamiliar texts, not just a prescribed corpus of memorized texts.

Jadids may have received their name for this pedagogical method, but their interests expanded far beyond the classroom. The classroom was simply a natural starting point because of the relative freedom the Russian colonial state allowed for religious minorities to regulate their own educational and religious affairs. The jadids’ interest in pedagogy was logically connected to their other ideas for reform. They believed that a new kind of literacy would lead to a social and political awakening. Through newspapers and theater—the production and consumption of which jadids’ functional literacy made possible—they proceeded to “awaken” their fellow Turkestanis to their ignorance by articulating a new interpretation of Islam compatible with European ideas of industry, economic growth, democratization, sexual morality, and women’s rights. Driving this was an ardent belief in their Turkestani Muslim nation and a desire to return it to the glory that it supposedly possessed in a previous age, which both jadids and their intellectual rivals located in the fifteenth-century rule of Tamerlane and his descendants. To “restore” their nation, they promoted a cultural revival of the arts and new forms of political engagement with the Russian imperial state. One of their chief achievements was the creation of a public sphere; newspapers and theater created new forums to challenge traditional authorities.12 That vibrant culture of public debate continued into the 1920s until it was severely circumscribed by the arrival of Stalinism.

Cho’lpon did not study at a jadid school, but in the mid-1910s, he began his literary career by publishing in jadid journals and joining discussion and poetry circles with these men. In 1914, he produced his first prose stories, “A Victim of Ignorance” (Qurboni jaholat) and “Doctor Muhammadiyor” (Do’xtur Muhammadiyor), both of which, like many jadid stories and articles of the time, employ characters without much depth to demonstrate the potential catastrophes of ignorance and the benefits of secular education in medicine, the natural sciences, and the humanities.13 These stories are largely didactic and lack aesthetic ornamentation. Towards the February Revolution, he met and became close friends with Abdurauf Fitrat (1887–1938), the most prominent jadid of the 1920s, who remained a mentor to Cho’lpon throughout his life.14 Fitrat pushed the younger man to engage more in poetry and reportedly suggested to him the pen name Cho’lpon—meaning “morning star” or “Venus”—because as a poet he stood out among his peers.15

When the February Revolution came, Cho’lpon and his fellow jadids were quick to embrace it. Muslims reformers saw in the revolution a chance to increase Turkestan’s autonomy within a new federation containing the territories of the former Russian Empire that would devolve power to the regions and champion democracy. Post-Soviet Uzbek historiography emphasizes that Cho’lpon and other jadids’ eventual goal was independence, not simply autonomy, but this interpretation ignores jadids’ precarious position in their own society. Jadids did not advocate independence because if Turkestan separated from the Russian state, they feared they would be left to the mercy of the ʿulama, who enjoyed more popularity among the masses than jadids.16 Because of jadids’ socially marginal position and their understanding of history as expressed in their literature, Cho’lpon and his compatriots’ literary works at this time portray the February Revolution as something of a deus ex machina: it appeared as a sudden and unprecipitated solution to their problems. In a country moving to the left, suddenly the jadids were on the right side of history.

Cho’lpon’s first published poem celebrated the February Revolution and socialist movements for these very reasons, seeing revolution as salvation from without. Published in 1918 but written in April of 1917, this excerpt from “Red Banner” (Qizil bayroq) demonstrates the poet’s interest in the democratic and anti-imperial politics promised by socialism.17 It is important to remember that the poem by no means signals support for the Bolsheviks, who were one among many socialist parties at the time. I have translated the below excerpt in a fashion that somewhat captures the caesura-inflected style of the original. The original contains fifteen syllables per line and is read with slight pauses every four syllables (4–4–4–3). The rhyme scheme, which I have not captured here, is abab.

Red banner!

There, look how it waves in the wind,

As if the qibla [direction that a Muslim should face when praying] wind is greeting it!

It is not glad to see the poor in this state,

For the poor man has the right because it is his.

Has the red blood of the poor not flown like rivers

To take the banner from the darkness into the light?

Are there no workers left in Siberian exile

To take the banner to the oppressed and weak people?

You, bourgeoisie, conceited upper classes, don’t approach the red banner!

Were you not its bloodsucking enemy?

Now the black will not approach those white rays of light,

Now those black forces’ time has passed!

The red banner, in scarlet red blood, that blood—the blood of workers,

Those oppressive executioners, those haughty classes, have spilt that blood,

The oppressed love more than anything that call to unite and awaken,

While those murderers, those upper classes, plug their ears!

Oh, seize the flag, wave it high over the oppressed,

The oppressed who have given their blood and lives.

From the workers, soldiers, and the downtrodden there will be greetings,

From the evil merchants, the bourgeoisie—only pain, sorrow, and grief.

From the angels—justice and satisfaction.

And from my pen, my paper, and myself—love!18

As is typical of jadid literature at this time, Cho’lpon underplays Central Asian agency in the toppling of the Russian Empire by showing the February Revolution here as an event to which Central Asians have contributed little. As the first stanza indicates, Cho’lpon describes the revolution, the red banner of socialism, as the active observer of a passive Muslim East. The banner is blown in the direction of the qibla, the direction of Mecca, suggesting that the socialists of Petrograd must take their revolution to the Muslim world. The conclusion of the second stanza highlights the passivity of Central Asians in the revolution by calling on the workers imprisoned and in exile in Siberia, outside Central Asia, to bring the banner to the “oppressed and weak people,” by which Cho’lpon means his own community. The reference to the blood and lives given by the oppressed to the red banner in the final stanza, in keeping with the view of Central Asians as passive, indicates that the revolution is not so much the product of their sacrifices as it is a cosmic gift given in redemption of their suffering. Throughout the poem, Cho’lpon adapts Chagatai poetic language to the politicized times by recasting traditional images used in mystical poetry into new roles. Blood, often used as a metaphor in Sufi poetry for mystical experience, is literalized here as “red blood” and becomes a call to political action, identified with the revolutionary cause.

Cho’lpon’s poetic persona of the 1920s was rooted in the complex intersections of ethnicity, class, and revolution in 1917 Central Asia. After the February Revolution, Russians and native Muslims, both ʿulama and jadids, jockeyed for power in Tashkent until October 27, 1917, when the Tashkent soviet, a committee of socialist railroad workers and soldiers allied with the Bolsheviks, took power in the city by force and declared itself sovereign over all of Turkestan. The soviet and its supporters were entirely European and therefore hardly representative of majority-Muslim Turkestan.19 While the ʿulama tried to negotiate with the soviet, which denied all Muslim claims to authority because there were no Muslim proletarians, many jadids left for the Ferghana valley city of Kokand where on November 27, 1917, they established the short-lived Kokand Autonomy. Cho’lpon, like other reformist Muslim poets, wrote several poems celebrating the formation of the Autonomy as a rebirth of his Turkic nation. In less than three months, once the Tashkent soviet could afford the expedition, it destroyed the Autonomy, killing thousands in the process.

After this juncture in 1917, Cho’lpon’s poetic output increased greatly. He spent much less time on marches and odes. Instead, contemplative and elegiac lyric made up the bulk of his poetic oeuvre in the 1920s. Perhaps his most famous work of this period is his 1921 lament “To a Devastated Land” (Buzilgan o’lkaga), an elegy for the destruction of Turkestan caused by the outbreak of war between the Red Army and Basmachi, the Central Asian fighters opposed to Soviet power.20 The following is a prose translation of an excerpt from the poem, which, like the previous poem, is written in a syllabic meter that alternates the number of syllables in each stanza. In the first part of the excerpt below there are fifteen syllables per line read this time with a caesura after the first eight syllables (8–7 and sometimes 8–4–3). The second part of the excerpt contains twelve and eleven syllables, read 4–4–4 and 4–4–3 respectively. The final two lines repeat the fifteen syllable structure of the first two lines. The rhyme scheme is aabbccdd.

Hey, mighty country whose mountains greet the sky,

Why has a dark cloud descended on your head?

.........................................................................

They have trod over your breast for many years,

You curse and moan, but they crush you nonetheless,

These haughty men with no rights to your free soil,

Why do you let them trample you without a murmur as if a slave?

Why do you not command them to leave?

Why does your freedom-loving heart not unleash your voice?

Why do the whips laugh as they meet your body?

Why do hopes die in your springs?

Why is your lot in life only blood?

Why are you so despondent?

Why do you no longer have that smoldering fire in your eyes?

Why are the wolves running through your nights so sated?

Why do those flying bullets not raise your ire?

Why is there such destruction across your plains?

Why do you not rain storms of vengeance?

Why has God forsaken you, sapped you of His strength?

Come, I will read you a little story,

I’ll whisper a tale of years past in your ear,

Come, I’ll wipe the tears from your eyes,

Come, let me look on your wounded body until I can’t look anymore.

Why is that poison arrow in your breast?

That poison arrow of an overthrown kingdom.

Why do you not desire vengeance?

Why do you not want the death of those enemies?

Hey, free land that has never known slavery,

Why is that shadowy cloud lodged in your throat?21

Nearly all readers, particularly Stalinist critics, saw through the thinly veiled metaphors here; Cho’lpon condemns the civil war and the Bolsheviks in particular. Indeed, the denunciations of Cho’lpon’s anti-Soviet views that began in 1926 referenced this poem specifically.22 The poem’s narrative pessimism, consonant with its elegiac form (the poem is a marsiya—the Persian genre name for a lament or elegy), is present throughout Cho’lpon’s oeuvre of the 1920s. Cho’lpon also exhibits here a fascination with nature that never left him throughout his career. He exercises personification and chremamorphism, the identification of people with animals and natural objects, extensively. Here the land becomes a woman whose breast has been trampled by invaders and conquerors. Cho’lpon’s lyric persona calls out to the effeminized land, just as he calls out to oppressed women in many other poems, desperately and unsuccessfully imploring them to rebel against its tormentors.

As the 1920s proceeded, Cho’lpon, justifying Fitrat’s confidence in him, became the most prominent poet among his Turkestani peers, not only because of his exquisite elegies, but also because of his formal innovation. He mastered a new form of versification, which was introduced to the Central Asian Turkic language around the time of the revolution, called barmoq (finger) meter. In previous centuries, Turkic-language poets wrote their works in ʿaruz meters, which were borrowed from Arabic verse via Persian. ʿAruz meters rely on the interchange between long and short vowels typical in both Arabic and Persian. When the meters were adapted to Chagatai in the fifteenth century, poets mapped the Persian vowel system onto the Turkic language because Central Asian Turkic did not have vowels of variable length. In the 1920s, Fitrat and others insisted on the adoption of barmoq, which had first been pioneered by Turkish poets in the Ottoman Empire, because it was, according to them, better suited to Turkic languages.23 Barmoq is a syllabic meter that requires an equal number of syllables in each line as we have seen in Cho’lpon’s poems above. Alongside barmoq meter, Cho’lpon and Fitrat also transformed the vocabulary of local poetry. Before the 1920s, Turkic-language poets wrote with copious amounts of Arabic and Persian words in a pedantic, often esoteric style. Cho’lpon pioneered a new Turkic vocabulary for poetry, writing in a language more understandable to the rural masses who were not literate in Persian. Fitrat and Cho’lpon’s interest in all things Turkic was not unique: the early 1920s saw an increased fascination with specifically Turkic culture, and jadids and other Central Asian intellectuals hailed the embrace of Turkic roots as a superior path to modernity.24

Despite these innovations, Cho’lpon was formally more conservative than many of his contemporaries. While he pioneered a new lexicon and meter, he retained much of the traditional imagery and themes of Chagatai poetry. Natural imagery, chremamorphism, themes of longing and loss are quite typical of Islamicate poetry, and Cho’lpon, like many in the canon before him, innovated by endowing this common material with new meaning, not by doing away with it altogether.25 In the latter half of the 1920s, Uzbek poets such as Oltoy and Shokir Sulaymon would take up the futurist poetics of Russian poets Mayakovsky and Kruchyonykh, experimenting with sound, speech registers, and graphic representation, but Cho’lpon never expressed interest in this kind of writing. His modernism, if we might call it that, was a homegrown one based on jadids’ new political consciousness and engagement with European thought about the nation.26 Cho’lpon’s art, as the coming pages show, emerges from a mix of traditional Islamicate poetics, new Turkic forms and vocabulary, an interest in the psychologism of proletarian prose, and an aestheticization of his political and historical philosophies.27

After the liquidation of the Kokand Autonomy, Cho’lpon began a bohemian life, moving from job to job and wife to wife. In 1918, he went to Russia as part of a travelling Uzbek theater troupe. There he made a lifelong friend, Mannon Uyg’ur, a theater director, and in Orenburg, he married a Tatar woman, Mohiro’ya, about whom little is known.28 In 1921, he accepted Fitrat’s invitation to work at Axbori Buxoro, the main newspaper of the People’s Soviet Republic of Bukhara, which was created in 1920 in place of the Bukharan Emirate, a protectorate of the Russian Empire within Turkestan.29 There he fell ill and was diagnosed with diabetes, from which he would have multiple stints in hospitals for the rest of his life.30 In 1923, pursued by Soviet critics and secret police, Fitrat left for Moscow, while Cho’lpon returned to his hometown of Andijon, taking up the position of deputy editor of the local newspaper The Emancipated (Darxon).31 In Andijon he married a woman named Soliha (whom he divorced in 1931).32 A quarrel with his father in the same year, likely over Cho’lpon’s reformist views, led him to abandon his home and move to Tashkent.33 In 1924 Cho’lpon was among twenty-three other Uzbek dramatists, directors, and actors selected to study in Moscow at the Uzbek Drama Studio, which had been established in 1921.34 Cho’lpon’s prior experience in theater made him ideal for this spot. While in Moscow, he became thoroughly acquainted with Russian literature and theater and may have even met with some of the Silver Age greats such as Mayakovsky and Yesenin.35

Drama became a large part of Cho’lpon’s oeuvre thanks to his time at the Uzbek Drama Studio. He had dabbled in theater before, but many of his major dramas came after his study of Gogol (he translated The Government Inspector [1836]), the Italian playwright Gozzi, and other dramatists while in Moscow.36 During that time, he became fascinated with the poetry and drama of Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali writer who in the 1920s was becoming well known among modernists throughout the world.37 In 1926, Cho’lpon reworked and published Bright Moon (Yorqinoy), a play he had written in 1920. Its mystical quality is close to that found in Tagore. He produced several other dramas after this point, but only two other plays, A Modern Woman (Zamona xotini) and The Assault (Hujum), survive.38

As Cho’lpon left for Moscow in 1924, Stalin initiated the national delimitation of Central Asia, a move that has commonly and mistakenly been interpreted as a surreptitious Bolshevik imperial strategy to “divide and conquer.” The 1924 delimitation created the Kazakh, Uzbek, and Turkmen Socialist Soviet Republics (SSR) (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan were autonomous republics within Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan until 1936 and 1929 respectively) from the Turkestan, Bukharan, and Khivan SSRs.39 Stalin made the decision based on his and Lenin’s attempt to combat Russian imperialist tendencies and defang bourgeois nationalism, which, according to Marxist theory, threatened the development of class consciousness by encouraging a false national consciousness. However, much of the implementation of Stalin’s decision—the negotiation of borders, the naming of communities, and the creation of common languages—was done by native elites like jadids. The Bukharan SSR, the government of which was composed largely of jadids and their allies, may have had more autonomy vis-à-vis Moscow than its Uzbek successor, but Uzbekistan, a homeland for Uzbeks, was the achievement of a jadid goal.40

In 1927, Cho’lpon returned to Uzbekistan to make use of his drama schooling by staging plays around the country. But a rude surprise awaited him. Around the middle of the decade, the Bolshevik Party felt that its hold on power in Central Asia was strong enough to take ideological control of the region. Beginning in the latter half of the 1920s, jadids and other old-generation national elites were expelled from the party in favor of a new generation of Uzbek intellectuals trained by the Komsomol (the Communist Youth League) and other party-associated organizations.41 Both Cho’lpon and Fitrat quickly became symbols of the old generation and were therefore attacked frequently in the press. Poets of the new generation who fancied themselves dedicated socialists attacked Cho’lpon for his poetry’s supposed decadence, pessimism, and anti-party views. Though they condemned jadids, we should not forget that many members of this new generation were students of jadids. They too believed in the need to spread education among Uzbeks, liberate women, modernize everyday life, and restore the Uzbek nation to its former glory, but they also saw themselves as superior to their predecessors in political will. They would achieve modernity for Uzbekistan where jadids like Cho’lpon had failed because of conservatism, timidity, and complacency. As a result of the attacks, several old-generation thinkers were arrested and exiled to Siberia. Cho’lpon escaped a probable arrest by again heading to Moscow in 1932.

During his second extended stay in the Soviet capital, Cho’lpon, like other persecuted writers across the Soviet Union, avoided controversy by reducing his publishing activity. He had never been a prolific poet: he published only three collections by 1932, Springs (Buloqlar [1922]), Awakening (Uyg’onish [1923]), and Secrets of Dawn (Tong sirlari [1926]). But around 1927, he largely stopped publishing original works and turned to translation. His friends and contacts in Uzbekistan’s Communist Party found him a job as a translator in Moscow.42 There he translated Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the first half of Maksim Gorky’s Mother (1907), and various works of Turgenev, Chekhov, and Leonid Andreev into Uzbek. He also met and married a Russian woman, Ekaterina Ivanovna (her surname is unknown).43

A lull in secret police activity allowed Cho’lpon to return to Uzbekistan in 1934. The latter half of the 1920s until 1932 was a period of denunciations, violence, and a strong push to construct socialism. Scholars have referred to these years, specifically 1928 to 1932, as the “Cultural Revolution.”44 The time is best known for Stalin’s annulment of Lenin’s NEP (New Economic Policy), the beginning of collectivization, the inauguration of the first five-year plan, and massive purges of the established intelligentsia in favor of inexperienced, politically engaged youth. The period that followed has been dubbed the “Great Retreat,” though recent research notes that Stalinism was not a total betrayal of revolutionary ideals; indeed, it achieved many of the economic goals of the Bolsheviks such as forced industrialization and collectivization.45 Nevertheless, when the first push to collectivize failed, along with other violent modernist projects, Stalin decided to make peace with the old intelligentsia and—to an extent—with traditional culture.46 These conciliations permitted Cho’lpon’s return.

Once back in Uzbekistan, Cho’lpon too decided to compromise with the Soviet state. He continued translating, rendering into Uzbek the second part of Mother, Gorky’s Egor Bulychov (1932), Alexander Pushkin’s Dubrovsky (1833) and Boris Godunov (1825), and the Iranian-Tajik communist Abulqosim Lohuti’s Journey to Europe (1934).47 He well understood why his poetry was criticized and attempted to rewrite his poetic biography. Because critics had lambasted him for the pessimism of his verse, his collection Soz (Lyre [1935]) emphasized his new optimistic persona and his enthusiasm for Soviet rule with poems such as “The New Me” (Yangi men) and “May First” (1 May), which celebrated international workers’ day. A 1934 poem, “Ten Years without Lenin” (O’n yil Leninsiz), panegyrizes Lenin on the tenth anniversary of his death.48 In 1934, he also submitted the first book of his dilogy of novels Night and Day to an Uzbek literary contest designed to encourage the writing of socialist prose.49

Determining Cho’lpon and other Uzbek litterateurs’ position on Stalin and Soviet politics at this time is fraught with complications because Soviet rule had rather ambiguous effects on the region. The Soviet system allowed jadids to pursue the creation of a nation-state, mass native-language education, women’s liberation through unveiling, and campaigns against Islamic clergy, the enemies of jadids.50 As for collectivization, it, oddly enough, did not produce the same disastrous results that it did in Ukraine and Kazakhstan. While rural Ukrainians and Kazakhs suffered and died of famine, Uzbeks were saved by the early fruit harvests in their warmer climate. New research suggests that many Uzbek farmers enthusiastically participated in dekulakization because they truly bore grudges against the richer peasants who cheated them and acted as usurers, as seen in Cho’lpon’s novel.51

On the other hand, the new generation’s attacks on their jadid predecessors demonstrated that Stalin had no tolerance for pluralism and democratic debate. How to implement the party line was a matter of negotiation, but the content of the party line was Stalin’s and Stalin’s alone. Many were dissatisfied with the failure of the Soviet Union to create an Uzbek proletariat; they harangued Moscow for turning Central Asia into a cotton plantation. Among themselves, they accused the Bolsheviks of imperialism and chauvinism.52 Throughout the late 1920s, the repeated failures to Uzbekify the party apparatus in Uzbekistan raised the ire of anti-colonial Uzbek thinkers. By the early 1930s, such efforts came to a complete halt. Native rule subordinate to Moscow continued, but only Uzbeks competent in Russian could climb the ranks.53 As for Cho’lpon, he must have been particularly incensed that his art and elegies had been the subject of frequent denunciations. Memoirists tell us that Cho’lpon, indeed, hated Stalin and wrote his fair share of poems mocking the mustachioed menace.54 The brief thaw in 1934 nevertheless offered some hope to the alienated, a chance for the Soviet Union to achieve the utopian ideals it had long promised, and therefore, we should read Cho’lpon and others’ moods at this time as extremely disappointed but also hopeful for change. After all, they had no idea what was coming.

What was coming was a new set of purges, commonly known as Stalin’s Great Terror, and Cho’lpon did not escape this time. Critics began denouncing him in the local press again in 1936. In 1937, he was called to 25 Stalin Street, the inauspiciously named location of the Uzbek Soviet Writers’ Union, to answer for his lack of productivity and other errors, but this meeting was only a prelude to his NKVD arrest. Cho’lpon now likely knew that his days were numbered because he decided to treat the terrifying situation with levity:

Figure 2. Cho’lpon’s mugshot in his NKVD file. Courtesy of Hamid Ismailov.

| Ziyo Said [a playwright]: | You had a word with [Mannon] Uyg’ur. |

| Cho’lpon: | Then we talked about Arabic words, but that’s a lie, I am not an Arab, I am not a nationalist. I hate Arabic, to hell with Arabic words. (laughter)55 |

Critics commonly leveled the accusation of “nationalism” against Cho’lpon and others, suggesting through the facile charge that jadids were hateful chauvinists opposed to Soviet internationalism. Soviet critics considered the jadid desire in the 1920s to purify the Uzbek language by ridding it of non-Turkic vocabulary as a particular manifestation of this “nationalism,” hence Cho’lpon’s mention of “Arabic words.” Cho’lpon first denies the charge, only to embrace it jokingly.

The NKVD arrested Cho’lpon on July 13, 1937.56 He was charged with membership in a secret counterrevolutionary bourgeois nationalist group, “National Union” (Milliy ittihod), that allegedly planned to overthrow the Soviet government and install a bourgeois one. The accusation had only a grain of truth to it: in the early 1920s, a group by the name “National Union’’ had brought together high-ranking members of the Turkestan and Bukharan communist parties to discuss strategies for increasing Turkestan’s autonomy vis-à-vis Moscow. The capabilities, ideological unity, and intentions of the group were, however, greatly exaggerated by the Soviet secret police.57 Others accused of membership in this and similar groups denied the NKVD’s charges, resisting for months while being beaten and tortured. Cho’lpon acquiesced almost immediately.58 It is unclear why he readily admitted to false charges, but Uzbek historians speculate that he knew there was no longer any point in resisting.59 On October 4, 1938, an NKVD firing squad executed him.60

His works, along with those of others who were executed alongside him like Fitrat, were banned in the Soviet Union from 1938 until Stalin’s death, though they circulated among Uzbek intellectuals and students in secret. After Khrushchev’s famous “cult of personality” speech at the twentieth party congress in 1956, both Cho’lpon and Fitrat were rehabilitated; however, publication of their works continued to be proscribed.61 Only during Gorbachev’s glasnost’, which began in 1987, did Cho’lpon’s works start to reappear in print. As the Soviet Union was falling apart, Uzbek intellectuals recovered Cho’lpon’s legacy. In the short period of glasnost’ before independence, they cautiously set him within the Soviet canon, arguing that he had been an unjustly persecuted and misunderstood pro-Soviet writer. Then, as the Soviet Union collapsed and the narrative of Uzbekistan’s historical victimhood took over, they transformed him into an anti-Soviet national visionary, a people’s poet, and a martyr for the cause of independence.

HISTORY OF THE NOVEL AND ITS PUBLICATION

It is unclear when exactly Cho’lpon began writing his Night and Day, but scholars speculate that he started around 1932 during his time in Moscow.62 As mentioned above, he submitted the first part of Night and Day to a contest for Uzbek socialist prose works towards the end of 1934. The judge, who wrote the report on the novel (Oydin, a major Soviet Uzbek poetess),63 noted that it lacked the proper ideological qualities necessary to be awarded a prize and expressed doubt that the proposed sequel, the content of which she seems to have known somewhat, would fix the political mistakes.64 Nevertheless, the judges collectively recommended the novel for publication.65 The first chapter of the novel was published in the journal Soviet Literature (Sovet adabiyoti) in the third issue of 1935, the second chapter was published in the tenth issue of Rose Garden (Guliston) in the same year, and the entire novel was published in October 1936 as a book. It received a short laudatory review in Young Leninist (Yosh Leninchi) in February of the following year, while all the other major critics held their tongues.66 Few dared to associate themselves with Cho’lpon publicly because of his reputation in the press. Only in August of 1937, three critics coauthored a scathing review after Cho’lpon’s arrest, targeting the writer for “replacing class struggle with pornography [parnografiya],” and “showing jadids as revolutionaries for the people” rather than as “allies of the Russian bourgeoisie and imperial officers.”67 The book was banned along with the author’s name.

Glasnost allowed its republication. In 1988, the novel was republished serially in Star of the East (Sharq yulduzi), the largest literary journal in the Uzbek language.68 Star of the East (Zvezda vostoka), the journal’s Russian-language counterpart, released a Russian translation the following year.69 Despite the freedom permitted by glasnost, the editors of the 1988 serial publication felt obligated to censor certain parts of the novel. Because Cho’lpon had been accused of anti-Russian nationalism, the editors removed references to Russians that could be perceived as chauvinistic, despite the fact that Cho’lpon probably did not identify with the characters who utter them. They also added an epigraph from Gorky to increase the novel’s Soviet credentials. As far as I can tell, there was little threat in 1988 that representatives from Moscow would be concerned with the anti-Russian sentiments of a writer repressed fifty years earlier. The editors had more to fear from Uzbek critics, some of whom likely participated in Cho’lpon’s repression and built their careers on it. Since Uzbekistan gained independence in 1991, Uzbek publishers began printing the novel as a reproduction of the 1936 edition transliterated into the Cyrillic orthography.70 Uzbek and Russian scholars produced another translation of the novel into Russian based on the uncensored manuscript in 1991, and Stéphane Dudoignon translated the novel from Uzbek into French in 2009.71 This translation of the novel follows the version of the text published in 1936 and post-1991 republications (some of these offer explanatory and textological notes), while the footnotes indicate where the text of the 1988 serial publication differs.

The sequel to the novel has served as the source of much controversy among Uzbek literary scholars. In all extant editions, the present novel is clearly labeled “Book one: Night,” indicating that Cho’lpon intended a sequel Day to complete the suggestion of the dilogy title, Night and Day. Naim Karimov, the foremost expert on Uzbek jadids, suggests that the projected sequel was merely a myth made to appease Cho’lpon’s Soviet critics and that Night should be considered a novel complete in and of itself.72 Dilmurod Quronov, a specialist on Cho’lpon’s prose, has argued the opposite. He contends that Cho’lpon not only planned a second novel but most likely wrote it before his arrest. In a 1937 article, Cho’lpon mentions his “novels” in the plural, and an unidentified incomplete work was discovered among his belongings upon his arrest.73 If the NKVD possessed a copy, the opening of their archives to a select few senior Uzbek scholars in the 1990s would have turned up the sequel. Because there has been no mention of scholars finding such a text, it is likely that the NKVD destroyed it as they often destroyed confiscated texts in the event that those texts could not lead to additional arrests.

READING AND INTERPRETING THE NOVEL

Most scholars have interpreted the novel as an attack on the Soviet Union and its socialist ideology, reading Cho’lpon as an unambiguously anti-Soviet author, but there are ample reasons to doubt this easy conclusion.74 Cho’lpon’s Night and Day is certainly unique for its time. Its language, plot, and interests are, as earlier noted, little like the canonized works of Socialist Realism, the demands of which would become increasingly stringent by the time of the Great Terror. However, scholarly accounts of the construction of the novel within the framework of Cho’lpon’s oeuvre and the literary and historical context of the time are almost nonexistent. All appearances suggest that Cho’lpon intended to reconcile with and show support for the Soviet government with this novel and its potential sequel, but much of his drama and prose from the late 1920s on pose more questions than they resolve. In his writing, he constantly reworks and revises assumptions, never ending on a sure conclusion that would clearly support or reject socialism. His prose emphasizes mistakes and misunderstandings, highlighting the characters’ ignorance of their surroundings. In showing his ideological loyalty, Cho’lpon borrows from the texts and techniques of socialist writers, but he mainly makes use of those practices that enhance the indecisiveness of his characters. Although his goal was to support socialist ideology and to write an ideologically correct novel, Cho’lpon’s commitment, first and foremost, was to an aesthetic of the indecisive, an aesthetic which emerged from his background in Muslim reform. The resoluteness required by late 1930s Socialist Realism was ultimately inimical to his method.

Scholars and contemporaneous observers have argued that Cho’lpon wished for his novel to scandalize and offend the Soviet establishment because its plot is nothing like the model Socialist Realist plot that lionizes a socialist hero and his victory over class enemies. The first recorded use of the term Socialist Realism was in 1932 in a speech given by the literary critic Ivan Gronsky, but its interpretation only solidified later in the decade, a few years after the writing of Cho’lpon’s novel.75 According to the Socialist Realist “master plot” outlined by Katerina Clark (2000), Socialist Realist novels realize the Marxist-Leninist theory of history allegorically. Marxism-Leninism held a dialectic unique from other Marxisms: the proletarian masses would, through education, rise from an original state of “spontaneity” to “class consciousness.” This dialectic was realized in literature through “spontaneous,” impetuous, decisive protagonists who hone and focus that energy with the help of a Bolshevik teacher into “consciously” directed action in concert with others.76 Canonical novels containing this plot include How the Steel Was Tempered (1934) by Nikolay Ostrovsky and Chapaev (1925) by Dmitry Furmanov.

Cho’lpon’s novel, however, begins with ignorance—his characters rarely understand themselves, others, and their surroundings—and does not advance much beyond that. The novel follows the paths of three characters that intersect at various points over the course of several years, ending in 1916, a year prior to the Russian Revolution. Night and Day opens with the girl Zebi, who has recently reached marriageable age. The beauty of her voice catches the ear of Miryoqub, the retainer of the Russian-affiliated colonial official Akbarali mingboshi. Although Akbarali already has three wives, Miryoqub encourages his master’s interest in Zebi and arranges a fourth marriage. During that time, Miryoqub meets a Russian prostitute, Maria, with whom he falls in love and agrees to leave Central Asia. As the new couple leaves for Moscow, Miryoqub becomes acquainted with a jadid, Sharafuddin Xo’jaev, and nominally becomes a jadid. After Miryoqub’s departure, the action returns to Central Asia, where Zebi’s new co-wives intrigue against her and her husband. Mingboshi’s second wife plans to poison her, but Zebi unwittingly gives the poison to Akbarali. Zebi is taken to court, convicted of murder, and sentenced to exile in Siberia. The incomplete paths of Miryoqub and Zebi imply a sequel that details their participation in revolution and return to Central Asia, but the near absence of revolution and socialist ideas in the first book has been used by both Stalinist and contemporary critics to argue for Cho’lpon’s anti-Soviet intentions.

That inference, however, forgets the political fluidity of the period from 1932 and 1934 when Cho’lpon was writing. After the failure of collectivization and the Cultural Revolution, Stalin permitted the reconciliation of many persecuted writers to the Soviet literary establishment. Cho’lpon, as we know, took full advantage of this. When Socialist Realism was first coined in 1932, its contents, form, and overall meaning were largely undetermined.77 Stalinist critics attacked Cho’lpon for his failure to match an ideal form of Socialist Realism, but that ideal only congealed during and after Stalin’s Great Terror. Before that time, demonstrating ideological loyalty in literature could take multiple forms.

Nevertheless, as critics have correctly pointed out, Cho’lpon’s poetry-in-prose style in the novel certainly suggests that ideology was not his priority.78 In Night and Day, Cho’lpon’s prose mimics the style of his own poetry. His novel is full of original and striking metaphors that bring Central Asian daily life into the very narration of the text. Of the star overlooking his heroine Zebi’s nighttime journey, he remarks: “the brightest star—so bright that it looked as if it were face to face with its onlookers—trembled as it burned like the eyes of a young girl cutting an onion.” In this example, Cho’lpon interweaves the scenery of the novel with the coming-of-age experiences of his female characters: in Cho’lpon’s time, parents prepared their daughters for a life of domesticity by exposing them at an early age to the demands of Uzbek cuisine, of which the onion is a major component. Metaphors connecting nature and Central Asian culture are a ubiquitous feature of Cho’lpon’s prose. We see it even in the first lines of the novel. When Zebi enjoys a brief moment of liberty, the narrator compares it to the blossoming and expansion implied by the Uzbek word for summer: yoz. This word is homonymous with the verb yozmoq, meaning to expand. Cho’lpon extends the metaphor by equating the impositions of her misogynist father with the contraction implied by winter. “If the cold old man hadn’t returned, the two young girls’ pent up tension from the long winter would have expanded [yozilgan] with the warmth of spring and produced even more mischief” (italics are mine—C. F.). Cho’lpon often associates Zebi’s father with winter, describing him as “cold” and his visage as a “brow from which snow falls” (a figure of speech for “glowering”). The effect of the description identifies Razzoq-sufi with a winter that limits his daughter’s freedom. This is hardly the straightforward prose style one would expect of an ideological novel.

Yet Cho’lpon attempted to reconcile his poetry-in-prose to Socialist Realism not long before his death. In a 1937 article, he locates the same approach to nature in the writings of Maksim Gorky, the father of Socialist Realism. “Gorky is a poet,” Cho’lpon writes, “His writings demonstrate that he is more than a prose writer; each sentence evinces a poet with a tender heart, a lover of beauty, and a writer enamored of nature. I myself love beautiful similes and images of nature and try to include them in every work of prose I undertake.”79 In the 1930s, Cho’lpon translated Gorky’s Mother, which had been declared the earliest Socialist Realist novel, into Uzbek and used his knowledge of Gorky’s style to justify his own. Indeed, Cho’lpon is correct regarding the elder writer’s style, though Gorky’s romantic moments were increasingly underemphasized in socialist criticism as the 1930s advanced.

Cho’lpon’s oeuvre has more in common with Soviet ideology than previous scholars of his work have acknowledged. Throughout his literary career after the revolution, Cho’lpon was deeply concerned with the question of Central Asian women’s liberation. Like many other jadids and contemporaneous Muslim reformers elsewhere, he believed that his society had unfairly limited women by confining them to the home, forbidding them to appear in public without the full-body covering known as the paranji, and restricting their educational opportunities.80 In their project to advance women in society, the jadids found a powerful ally in the Bolsheviks. Progressive Russians had long been concerned with what they called the “woman question” and in the 1920s advocated for the full equality of women with men. The Bolsheviks, particularly those among the younger generation, were far more radical than Central Asian reformers, calling for the end of the family in order to create radical equality among the sexes.81 In 1927, jadid-influenced women, supported by the Bolsheviks, launched “the assault” (hujum)—a campaign for women to remove their paranjis. The “assault” met with a considerable backlash from patriarchal Uzbek men, who used violence to keep women in their place.82 Cho’lpon, for his part, supported the hujum through his dramatic work in the late 1920s, translating from Russian and authoring a few songs for the musical drama The Assault (Hujum [1927]) by Vasilii Ian (1874–1954).

Cho’lpon’s drama A Modern Woman (Zamona xotini [1928]), unpublished in his lifetime, is initially aligned with Soviet ideology in its support for women’s liberation, but because of the ambiguity characteristic of Cho’lpon’s art, the play questions the end result of those politics. Ultimately, it demonstrates contradictions within Cho’lpon’s own self: in his lyric he bemoaned the ignorance and docility of Turkestani women, but here he exhibits ambivalence toward his heroine who overcomes that passivity. The play’s final act shows the principal female character and the eponymous modern woman, Rahima xola, in the role of a successful head of a village ispolkom (executive committee). She scolds and punishes corrupt officials, religious authorities, and village misogynists, but the play ultimately concludes on a tragic note. To reach her position Rahima xola has to sacrifice part of herself, namely her femininity. Cho’lpon emphasizes throughout that the modern woman is actually very masculine. Rahima xola is described in the character descriptions as erkaknusxa (literarily: man-copy) and in becoming the head of the ispolkom, she takes on what is traditionally a man’s role. In fact, she ousts her husband, Rustam, from that position after he beats and almost kills her with a knife laden with symbolism. The knife is suggestive of a phallic object not just in a Freudian sense, but also in Uzbek culture in which a knife appearing in a dream or in an act of fortune-telling portends the birth of a son. When she becomes head of the ispolkom herself, she in turn beats “backward” interlocutors with an equally phallic whip. In the play’s conclusion, she announces her decision to marry the emasculated and sexless Jo’ra, an old man who has never married.

In a short soliloquy, Rahima xola regrets that her husband abandoned her and that Jo’ra cannot replace him. At that moment, Rustam bursts in and again confronts her with a knife. The stage directions suggest that her femininity returns in this final scene. According to those directions, her cries and wails are to “fully express her womanhood.”83 The police interrupt their encounter and arrest Rustam, but as they drag him away, the couple’s son, Adhamjon, chases after Rustam, calling “father, father” and ignoring his mother’s cries. The tragedy on which Cho’lpon ends his otherwise empowering play demonstrates the author’s uncertainty about both the Soviet and his own program for the future Uzbek woman. Rahima xola, the author hints, may be a liberated woman, but she cannot be a father to her son. His verse frequently lamented the passivity of women, but Cho’lpon here discloses his discomfort with the solution his earlier critique implied. A powerful female protagonist cannot maintain the femininity that Cho’lpon in his verse hails as authentically Uzbek and worthy of saving.

Through this conclusion, the play suggests that women should not have to defend themselves at all and that Central Asian men have forgotten their roles as protectors and heroes. Rahima xola’s husband Rustam’s name is no accident, for it alludes to the hero of Ferdowsi’s Shahname (The Persian Book of Kings). Cho’lpon’s Rustam, however, is a degenerated hero who has lost touch with his roots. Instead of using his strength to protect his wife and fellow villagers, he consorts with prostitutes, drinks, and beats his wife. Cho’lpon thus leaves his Rahima xola in an unresolvable situation: her husband refuses to act responsibly, and the author condemns her to tragedy for taking action herself. Despite the novelty of this figure in Cho’lpon’s oeuvre—powerful heroines like Rahima xola were popular in the dramaturgy of the hujum and Cho’lpon’s drama is something of a parody—Cho’lpon grants her a tragic fate all the same. In denying her a happy end, Cho’lpon expresses his ambivalence to the problem of women’s emancipation.

Cho’lpon’s unabating interest in ambiguity and the unresolvable is the product of his aestheticization of jadid political rhetoric and philosophy of history as expressed in jadid literature. Like other Islamic reformers of previous generations, many jadids saw history as a cyclical series of declines and ascents away from and towards civilizational peaks.84 In jadid literary works, the main agent in this history is God, not Muslims, and only His actions can renew Muslim society. The reformers’ role was to attune their ignorant brethren to the will of God so as to return the community to His favor. Jadid works across genres therefore depict the time of decline and ignorance in which they felt their society existed and then conclude, before the revolution, with a catastrophe, often sent by God, which warns readers and spectators of the follies of their ignorance, or, after the revolution, with salvation in the form of a deus ex machina, often the revolution itself. Though jadids certainly exercised agency in their society, much of their literature does not reflect that fact and instead, suggests that salvation comes from without. The depiction of ignorance naturally suggested certain rhetorical modes—elegy and lament of lost glory, exhortation and admonition to regain that glory, or satire of the time of ignorance—all of which became the favorite rhetorical modes of jadids. In the early 1920s, several jadids came to the realization that their art, as expressed in the above rhetorical modes, emerges precisely from the depiction of decline. They therefore endeavored to indefinitely defer the moment of consciousness in order to fully exploit the aesthetic possibilities of ignorance. Ironically, the jadid aesthetic came to work at cross purposes with jadid politics: while their politics called for an end to the age of ignorance, the jadid aesthetic demanded its continuation. This aestheticization of ignorance explains Cho’lpon’s ambivalence to the events he depicts in the novel. On one level, he detests the ignorance of his countrymen and desires that they awaken, but on another, he is fascinated by the opportunities for creativity that ignorance permits.

Cho’lpon’s 1920 poem “Someone’s dream” (Xayoli) beautifully demonstrates how the author reconfigures ignorance from the object of political condemnation into an engine productive of artistic material. Cho’lpon in this poem suggests that there is a creative energy in sleep, in unconsciousness—jadids often implored their brethren to “awaken” from their “ignorant slumber”—which is maintained by its unfinalizability or unrealized potential. To wake up from such a sleep is to lose something of the possibilities engendered by that sleep’s dream. This poem has a syllabic meter of eleven syllables per line and is read with a caesura every four syllables (4–4–3). The rhyme scheme, which I have captured here, is abcb.

I hid the spark of love inside my heart,

Tucked it away in the depths of my dream.

Concealed in my bosom, the wound from that spark

Burns and burns, tearing each stitch at the seam.

I hear: “take your desire” from

The morning [azonlar] with its dev’lish voice;

But I ignore it and continue my tales,

Thanking the angel that granted me choice.

That devil, toying with its hair,

Responds in anger: “Your stories are all in vain!”

Its words arrive at my ear changed:

“I flow,” it says, “like blood from red and golden veins.”

“Now flow with me,” it says, “you lord of tales,

Await in me all your desires and your throne;

In that golden and bloodred water,

Your soul, once clothed in black, will take on new tones.”

Leave me, oh devil, torture me with nightmares no more.

My shield is broken, my sword in two snapped.

Do you see me? I’m crushed, and I lie now,

Under a mountain of misfortune, trapped.

Oh angel, at my last breath, still I am enthralled,

Come, look at me, and let the heavens fall.85

The artistry of this poem is closely related to its lack of a conclusive awakening. A devil, tempts the speaker to awaken from his sleep—I have rendered azonlar, the calls to prayer, as “morning” to show how the poet continues his metaphor of dream—and achieve the “desire” of his dream in reality. That devil identifies the lyric persona as an artist—“lord of tales.” In declaring that the persona’s “stories are all in vain,” the devilish voice invites the artist to stop toying with the artifice of dream; however, the speaker refuses because he finds art, the ability to weave his tales, within dream. Cho’lpon then ends the poem not with the happiness and prosperity—that is, awakening—that the devil offers but with a crushing death. Rather than exiting the state of ignorance for which sleep and dream were so often metaphors in the literature of his jadid predecessors, Cho’lpon chooses to remain within that state, even as it leads to a tragic end. By rejecting an exit from dream because of the artistic play it permits, Cho’lpon suggests that art emerges from the indefinite deferral of awakening.

This aesthetic of ignorance on display in “Someone’s dream” is Cho’lpon’s main structural device in Night and Day. Drawing on this aesthetic and the author’s experience as a dramatist, the novel is filled with dramatic irony: the characters are ignorant of their political, social, and familial environments. They know far less about their predicaments than we as readers do. The plot develops through self-discoveries, but these are always preludes to further epiphanies, and thus character development is a never-ending process. Ultimately, every discovery or recognition is a misrecognition that postpones enlightenment to another time.

The inability to understand one’s self and others plays a large role in the novel’s character interactions. Cho’lpon, perhaps because of his education in Russian literature during his two periods in Moscow, frequently employs one of Tolstoy’s favorite techniques—that of non-verbal communication. Often his characters communicate not so much through words, but through glances, gestures, body movements, and facial expressions. For Tolstoy, a longtime lover of Rousseau, this bodily communication is closer to nature and thus conveys more than do words, which are abstracted from nature and therefore false. For Cho’lpon, on the other hand, non-verbal communication often indicates that something remains indeterminate and unable to be articulated. For example, after their trip to the village, Zebi’s friend Saltanat realizes how her actions have unwittingly begun the process of Zebi’s betrothal to Akbarali. She decides not to tell Zebi to avoid upsetting her, but after imagining Zebi’s life with Akbarali, she involuntarily screams and embraces her friend. Even when Zebi later discovers Akbarali’s plans, she never quite understands Saltanat’s embrace:

Suddenly she remembered Saltanat’s behavior in the cart: Saltanat had cried out “mingboshi!” She had become pale and lost consciousness. When she opened her eyes and stared at everyone, she then looked directly at Zebi and threw herself into her arms. Then two days ago Saltanat’s mother came and conducted a conversation in whispers with her mother. Since then, her mother had looked like she was constantly mourning.

Oh, if only Saltanat were with her now! She could have shared these things with her, and Saltanat would have comforted her, right? Did Saltanat already know? Wouldn’t she have said something in the cart if she knew? They talked the whole way, and she didn’t say anything about this. Or could she have been hiding it? If she was hiding it, was she really Zebi’s friend? What kind of friend is that?

As seen in this passage, bodily communication inadequately replaces speech. Saltanat says only one word, mingboshi, and expresses her thoughts largely through looks and embraces. Saltanat’s embrace, meant to relay her remorse and misery at not sharing her secret with her friend, fails to achieve its goal. At the time of the embrace, Zebi is dumbfounded, and later she understands only betrayal in that hug and not Saltanat’s perhaps misguided, but well-meaning intentions. Saltanat, to Zebi’s chagrin, does not speak to her.

The characters’ ignorance of their surroundings and themselves is further reflected in the way Cho’lpon describes actions. A surprising number of the main characters’ movements are depicted as involuntary. Cho’lpon, for example, describes Zebi’s unwitting attraction to the young O’lmasjon with the following: “at that moment, her voice became alien to her. The voice producing those words sounded to her ear as if it came from the far side of the creek.” Like many of Cho’lpon’s characters, Zebi cannot account for her own actions. Zebi often feels as if another entity has control over her, such that she acts contrary to her will.

Cho’lpon’s narrator openly sympathizes with his characters, but also criticizes and mourns their lack of self-consciousness. He inserts himself into the story to mourn Zebi’s situation and the societal imprisonment of women:

Why don’t the poor women who grow up inside four walls, who don’t see anything other than the sharp looks of those permitted inside, sense the tragedy of their sheltered lives? If they are so used to seeking little joys inside their four walls, can these poor things ever believe that the shameful joys which wander in from outside are part of something greater?

The narrator’s interruption here is little different than the work his lyric persona performs in his poetry. We have already seen how Cho’lpon’s lyric persona bewails his war-torn homeland in his 1921 poem “To a Devastated Land” by likening it to a silent, slavish woman, and here we see the same rhetorical strategy.

Ignorance becomes a structuring device not just through Cho’lpon’s prose style and narration, but also through plot structure. Misjudgment, miscommunication, and misrecognition provide most of the turns in the narrative. Akbarali’s youngest wife, Sultonxon, invites Zebi to her house without grasping the consequences—that Akbarali will fall in love with Zebi and that Sultonxon will lose her status as favorite wife. Zebi’s father warns her not to sing during her trip to the village, but losing herself in the moment she releases her voice, which leads to her eventual marriage to Akbarali. One of Akbarali’s elder wives, Poshshaxon, mistakenly murders him when she intends to poison Zebi, which leads to the novel’s climactic trial. Miryoqub and Maria constantly misunderstand one another, unable to speak the same language. Each mistake draws the characters out of their usual environment and transforms them. Sultonxon, a naïve young girl, realizes the pain of her elder co-wives. Zebi, a poor girl at the beginning of the novel, is forced into a life of luxury with a man who revolts her. Miryoqub and Maria wind up married after a disastrous misunderstanding, which should have separated them forever: Miryoqub gives Maria a check, signifying, to him, his loyalty but, to her, that he sees her only as a prostitute. That such mistakes, even at the novel’s conclusion, continue to dictate the action, undermines the sense of closure that the epiphanies experienced by characters in the course of the novel may suggest.

Because incomplete epiphanies play a role throughout the novel, we should regard Miryoqub’s conversion to jadidism, the conversion which both Soviet and post-Soviet authors have cited as evidence of Cho’lpon’s anti-Soviet stance, as an unfinished transformation and not necessarily a product of Cho’lpon’s antagonism towards the Soviet Union. Miryoqub is, at times, as Soviet critics accused, a scheming capitalist, a sexual profligate, and very nearly a jadid, but Cho’lpon’s narrative emphasizes the ephemeralness of these identities and denies them authorial approval. Miryoqub undergoes a number of epiphanies based on the contradictory advice he receives from various interlocutors and as a result of his own self-questioning. In several episodes that take place only in his mind, his self is split in two, and one half of Miryoqub submits the other to an eerily prescient interrogation à la the NKVD. Cho’lpon no doubt knew about the many secret police arrests and questionings of the late 1920s and early 1930s, but the interrogation in the novel has literary precedent, as discussed below. Interrogator-Miryoqub attacks his other self for his sexual licentiousness and callousness toward women, but in those interrogations, the Miryoqubs’ capitalistic inclinations always win out. The defendant Miryoqub justifies his every transgressive sexual act by arguing for his lack of choice in the matter or by suggesting it as merely a way towards greater wealth, which appeases the money-grubbing interrogator. Miryoqub assuages his conscience of his guilt in several matters by persuading his greedy interrogator, but the reader senses that Miryoqub is letting himself off easy with unconvincing arguments. Miryoqub, Cho’lpon therefore hints, will have further epiphanies still.

Those familiar with jadid literature once again doubt the conclusiveness of Miryoqub’s epiphany when he meets the jadid Sharafuddin Xo’jaev and seemingly becomes a jadid. His conversion to jadidism is noticeably undermined by the parodic nature of the text in this episode. Because Miryoqub and Maria cannot communicate with one another—neither know the other’s language—Cho’lpon formats the pair’s meeting with the jadid Xo’jaev in a train headed to Moscow as a series of hypothetical diary entries, the collection of which he calls a sarguzashtnoma (travelogue). The travelogue genre went by many names in Turkic and Persian Central Asian letters. Zokirjon Xolmuhammad o’g’li Furqat (1859–1909), a generation previous to the jadids, is the only writer to use the term sarguzashtnoma, but whatever its name, the travelogue genre in jadid letters had a few fixed attributes which proved ripe for Cho’lpon’s parody.86 Jadid travelogues are monologic texts: they beat their readers over the head with an uncompromising view of progress and ruthlessly criticize Central Asian society by comparison with others. Cho’lpon’s sarguzashtnoma parodies these previous travelogues by way of its dialogism. The jadid Xo’jaev, more pamphlet than person, speaks like the narrator of these travelogues: he praises the benefits of education through European examples and berates the backwardness of his countrymen. But his speech passes through the prism of Miryoqub’s hypothetical diary in which Miryoqub questions and misunderstands him. At the end of their encounter, Miryoqub notes that he does not entirely trust jadids:

Now I will never say that the path of our fathers is the only one. But I can’t say that the jadids are right either. Though I do understand what the jadids have to say more easily and quickly than what others say. Is it just that they talk well?

Cho’lpon’s sarguzashtnoma furthers his parody of this genre of Muslim reform through yet another level of dialogism. Xo’jaev’s diatribes are read opposite Maria’s hypothetical diary, which often directly contradicts the jadid’s rhetoric. Xo’jaev implores Miryoqub to idolize Maria as a culturally superior individual because of her Russian background. She, Xo’jaev argues, will teach Miryoqub and his children to be cultured and educated individuals. But Maria’s hypothetical diary entries show us her utter ambivalence to culture and education. At times, she desires a more enlightened Miryoqub, and at others, she envies his new relationship with Xo’jaev:

I’ve been reading my fortune and “unhappiness” keeps coming up. Not promising. He’s going to take my Jakob [Maria’s name for Miryoqub— C. F.] away! Is there anything worse than this culture? That cultured sart does nothing but talk from morning to evening.

As is common in Cho’lpon’s treatment of women, here Maria exhibits a fickleness that undermines readers’ impression of her character, but this time it also undermines Xo’jaev’s confidence in Maria’s cultural superiority. Central Asian jadids often condemned Muslim women as ignorant for their engagement with superstitions and magic. Ironically, the Russian woman Maria’s fortune-telling with her cards is just the kind of “backward” behavior that a jadid like Xo’jaev would have condemned in Muslim women. Likewise, Xo’jaev rants about the vices of Tashkent, among them prostitution, as instruments that deprive Muslims of their agency, and yet he praises Maria, who, unbeknownst to him, is a former prostitute. Cho’lpon’s support of his jadid character and Miryoqub’s conversion to jadidism is hardly without irony and ambiguity.

Not only does Cho’lpon parody and ironize jadid rhetoric in the novel, but he also plainly paints Xo’jaev and the novel’s other Muslim reformer character, the inspector of village credit unions, Hasanov, negatively, imbuing them with the fictitious anti-Soviet qualities for which jadids were condemned in the late 1920s and 1930s. In the train, Xo’jaev repeatedly attacks Russians as the absolute enemies of Muslims, a chauvinistic view more consistent with the negative Soviet portrait of jadids than actual jadid thought. Cho’lpon’s Xo’jaev says of Russians:

We hate those people. They are our enemies! They are our enemies in every sense! It’s not so often that we find a friend from among them. But those that we do find are good. Very good friends. But when we embrace them, we’re always ready to escape their clutches!