Читать книгу King Solomon and the Showman - Adam Cruise - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеA Journey with Gun, Camera and Notebook

Early the next morning, I was woken by a crunching sound just outside the tent. Being careful not to make a noise, I peeped tentatively outside, and found myself nose-to-muzzle with a cow munching on the grey seedpods scattered under the trees where I had pitched my tent. The big brown beast, with an impressive set of horns, wasn’t too surprised at the sight of me: it simply lifted its square head to meet my gaze, as if to say, “Do you mind? I’m having breakfast,” before it went back to its meal. After getting dressed I stepped out into the cool morning air to be greeted by a herd of about twenty, which had surrounded the tent. Most were intent on hoovering up every pod on the ground but a few managed to crane their necks long enough to pluck some from between thorns on the hanging branches.

Like its distant cousin the cow, the giraffe has always favoured this tree for its crunchy seedpods. It is said that they liked them so much that their necks grew as they strove to reach the juiciest pods higher up in the tree. Of course, this is a gross over-simplification of the evolutionary process. But the association between giraffes and their preferred source of sustenance has been immortalised in the name of the tree: the camelthorn. In Afrikaans a giraffe is called a kameelperd, a camel-horse. Now, long after European travellers shot the giraffe to extinction in these parts, the camelthorn is a poignant reminder that these animals once thrived on the desert plains. That morning, however, I was mostly grateful that the cows shared their culinary preference. Being less well adapted to desert life, their presence meant I was close to permanent water – and humanity. So, after enjoying a cup of coffee, using up the last of my water, and breaking camp – which involved a little pushing and shoving of bovine flesh – I followed the cattle path heading northeast.

Gradually, the path improved, morphing from an indeterminate track peppered with cattle spoor, to a set of parallel tyre tracks, to a graded gravel road with road signs. Finally, a few hours after leaving the cattle herd, I arrived at the village of Lehututu, named after the call of a conspicuous bird in the Kalahari, the African grey hornbill. The ubiquitous birds perch at the tops of camelthorns, raise their heads and heavy curved bills skyward and whistle shrilly hew, hew, teoo, teooo, teoooo.

Lehututu was a welcome base for replenishing my water supply and reorienting myself. It also boosted my resolve to continue my search for Farini’s Lost City because, by his own account, he had been there. At the time he passed through, it was just a small baTswana village of round huts; the walls constructed of mud, sand, grass and cow dung that created a strong cement-like compound commonly known as dagha. All the huts had thatch roofs supported by a pole in the middle. Even today, many abodes in Lehututu are constructed like this, although I noticed that rectangular structures of brick and mortar are beginning to take over the architectural landscape of the village. More important to me than Farini’s visit to the place was that Lehututu was the closest settlement to where he claims to have seen the ruins.

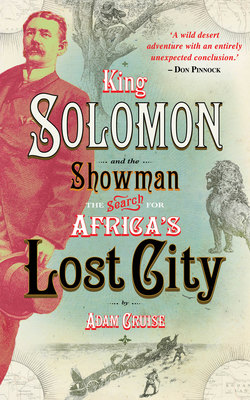

The first time I came across the name Farini was in 2005, inside the covers of a Christmas gift. I had received a copy of Alan Paton’s hitherto unpublished account of an unusual adventure he undertook in 1956. The celebrated author of Cry, the Beloved Country had been persuaded by a fortune-seeking adventurer named Sailor Ibbetson to go on a harebrained expedition into the Kalahari Desert to search for Farini’s Lost City. Ibbetson was obsessed with what had already mushroomed into a legend and somehow persuaded Paton to accompany him and a group of amateur explorers in a dilapidated five-ton truck on “the craziest expedition ever to enter the unknown”. Before then, Paton had never heard the name Farini, but like any good writer he allowed himself to be drawn in by Ibbetson’s scheme. In his resulting book, Lost City of the Kalahari, Paton describes Farini as an American cattle rancher who came to the Kalahari fired up by tales of “grass-covered plains, its teeming game and its diamonds” and came away the discoverer of a Lost City. I was hooked.

I learnt from Paton that Farini had written a book extravagantly entitled Through the Kalahari Desert: A Narrative of a Journey with Gun, Camera, and Notebook to Lake N’gami and Back. With some difficulty, I obtained a copy from the British Library, which had printed it from the original housed in the British Museum. It was a fairly voluminous work, complete with sketches, tables, inventories and a map, plus lengthy details on the fauna and flora of the region. Despite the detail, I agree with Paton’s impression of it as a galloping and entertaining read. The narrative bounds along at a pace that makes it difficult to put down, even by today’s standards.

A wonderful feature of the book is the series of sketches, apparently based on photographs taken by Farini’s foster son, Lulu. Then in his late twenties, Lulu was a talented photographer who had taken along an early version of a portable camera, complete with dry plates, which he had to preserve for months on end in hot, dusty conditions. This was some feat. Even in the modern era, with the luxury of a climatically sealed truck cabin, it is almost a hopeless battle to prevent the dust and heat from destroying my camera equipment. I have broken three camera housings and scratched half a dozen expensive lenses, thanks to the fine red dust of the Kalahari. Lulu somehow prevailed. He must have been one of the first, if not the first, to photograph Kalahari scenes and landscape. His photos are preserved for posterity at the National Archives in the United Kingdom.

According to Farini’s narrative, the journey in a light buckwagon took eight months to complete. He was accompanied by his foster son, a German itinerant salesman named Fritz Landwehr whom they picked up along the way, a handful of servants, local guides, mules that were soon switched for much hardier oxen, some horses and a pack of hunting dogs. The Farinis did a train journey from Cape Town to Kimberley, where they collected a wagon and supplies. They then travelled to the Vaal River, crossing it at Schmidtsdrif before heading west past Griqua Town to the Orange River at Wilgenhoutsdrif. There the party struck out north, trekking to the isolated trading post of Khuis on the Molopo and then on to Lehututu, which Farini misspelled Lehutitung, in what today is the Matˆsheng district of the Kgalagadi region of the southern Kalahari. In 1885, precisely as Farini travelled through, the predominantly uncharted area between the Orange River and the 22˚ South parallel was in the process of being proclaimed for the British Crown, soon to be the Bechuanaland Protectorate. It was a move aimed primarily at halting the expansion of both German imperial and Africanised Dutch (Boer) republican designs.

After Lehututu, Farini and his party travelled up the western border of the would-be Protectorate and the German territory of South-West Africa (now Namibia), passing the remote European hamlet of Ghanzi. The explorer apparently got as far as Lake Ngami (he wrote N’gami) where he shot an elephant. Lake Ngami had already been ‘discovered’ by explorer David Livingstone, who came in from a different direction in 1849, but Farini then went further northwest to an area he recorded on his map as Bell Valley before looping back, taking a south to southwesterly route roughly along the eastern boundary of German South-West Africa. They passed Tunobis, then a settlement of Herero, a tribe Farini describes as “powerfully built… with the splendid physique of the Zulus”. After Tunobis they trekked south all the way to what was then the quasi-independent Baster nation of Mier. Baster is Afrikaans for bastard, referring to a large group of mixed-race immigrants, originally from the Cape Town region, who had escaped the racial oppression of their European masters. The majority were the offspring of Dutch farmers and their Malaysian, Indonesian or Khoe-Khoe slaves. They proudly referred to themselves as Basters, distinguishing themselves from the indigenous people and the slaves of ‘pure’ blood.

Mier country was and is characterised by a vast expanse of waterless desert dune country interspersed with white salt-encrusted pans and the dry, south-‘flowing’ watercourse of the Molopo River. In 1885 the area was deemed so worthless that the British, Boers and Germans, whose territories surrounded the region, wanted nothing to do with it. Mier’s de facto jurisdiction fell under the autocracy of a Kaptein or chief by the name of Dirk Vilander. His capital, where Farini convalesced for a few days, was the hamlet of Rietfontein, which still exists. It is on the border with Namibia and a little to the west of the twenty-five-kilometre-long Hakskeen Pan.

From Vilander’s headquarters, Farini and co. embarked on a protracted hunting spree in the vast area that now makes up the Botswana section of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park to the north and west of the Nossob River. Their point of departure from the left bank of the Nossob valley, wrote Farini, was Ki-Ki (pronounced kai-kai). It also still exists – as a water hole in the game park – but with the modern spelling Kij-Kij.

After a couple of weeks of hunting in the scattered wood and grasslands north of the Nossob somewhere to the southwest of Lehututu, shooting almost anything that wandered in front of his rifle’s crosshairs, Farini returned via Kij-Kij to Rietfontein. It was on the return journey, before the party reached Kij-Kij, and in the general area where I had just been, that Farini discovered the ruins. He even marked it with the word ‘ruins’ on the map that appears in his book and on the one he submitted with his paper to the Royal Geographical Society. On both maps ‘ruins’ appears alongside a watercourse running from north to south into the Nossob River, and next to what appears to be a pan.

The description of the ruins in Through the Kalahari Desert is dealt with almost as swiftly and without much more flourish than in the paper presented to the two geographical societies. It’s as though Farini added it to relieve the monotony of his endless hunting escapades that dominate this section of the narrative. He did, however, provide some more information about the stone relics, describing them as “a Chinese wall after an Earthquake” and that they were “quite extensive”. In his book, instead of the ruins being described as an eighth of a mile long, as stated in the papers, they mysteriously become a mile long; and the flat-sided stones are now joined together by cement.

Three other crucial elements stand out in the book’s account of the ruins. Firstly, there’s a sketch of the ruins, apparently from a photograph taken by Lulu. In the foreground, on the right, is a rectangular block balancing precariously on a stone column with others lying about on the ground around it. In the middle ground of the drawing the pavement mentioned by Farini intersects at right angles to form a cross, but, tellingly, no altar is depicted. A stone stump of what seems like a roundish fluted column sits in the background among some bushes. This is the image that has come to define the Lost City. Unfortunately, the corresponding photograph is not to be found in the National Archives collection.

The second thing unique to the book is that Farini provides more detail on the location of his ruins. He states that when they stumbled upon them, they were three days north of the Ki-Ki Mountain, a well-known landmark presumably next to the waterhole of the same name. The ruins themselves were discovered two days after they left a forested belt similar to the one I had spent the night in. As they moved south, the trees became “more and more scanty”. One of Farini’s Baster attendants had thought they were already at Ki-Ki Mountain but Farini claims “they were not far enough south for that.” This false Ki-Ki Mountain “turned out to be one that nobody seemed to have ever seen or heard of”. After they left the false one they reached the real Ki-Ki mountains, having “travelled all the way over a gentle slope” for a further three days. There they found the reservoir with enough water in it to enjoy “the delight of a real swim, after having been many months without one…”

The third element was that Farini, an aspiring poet, proffers three verses of doggerel, which give the only true insight into what his opinion of the ruins was:

A half-buried ruin – a huge wreck of stones

On a lone and desolate spot;

A temple – or a tomb for human bones

Left by man to decay and rot.

Rude sculptured blocks from the red sand project,

And shapeless uncouth stones appear,

Some great man’s ashes designed to protect,

Buried many thousand a year.

A relic, maybe of a glorious past,

A city once grand and sublime,

Destroyed by an Earthquake, defaced by the blast,

Swept away by the hand of time.

It’s the first time the word ‘city’ is mentioned in reference to the ruins.

After their hunting foray, the party journeyed south along what, on Farini’s map, is marked the ‘Hygap River’ but is now recognised as the lower reaches of the Molopo. Farini reached the Orange River at the Augrabies Falls. After some days there, the party returned to Cape Town via Hopetown with a pair of what Farini called ‘Earthmen’ – otherwise known as ‘Bushmen’. These diminutive folk were San-speaking hunter-gatherers from the Lake Ngami area who apparently agreed to accompany Farini by ship to London.

Farini’s book was fairly widely read after its publication in March 1886, and by and large received favourable reviews, but intriguingly without much, or any, curiosity about what was potentially a significant discovery. A fair amount of interest was taken in other aspects of the book, such as the details of the landscape, the different people he encountered, the fauna, and in particular, the flora. Farini was an accomplished botanist and was able to record in minute detail a vast array of plant species he came across. Informed sources at the time, notably the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, the founder of British geographical botany and a close friend and associate of Charles Darwin, declared it “a standard work on the subject of the Kalahari”.

While it is strange that there was a distinct lack of fanfare surrounding Farini’s discovery of the ruins, it is even more curious that when he arrived back in England (on 13 August 1885) from his Kalahari adventure, the streets of London were bedecked with posters and billboards announcing the imminent publication of “The Most Amazing Book Ever Written”.

But it was not Farini’s book. The novel, which was to cause a storm of fictional Lost City mania, was King Solomon’s Mines, penned by Henry Rider Haggard, who, just two years before, had spent a considerable amount of time in southern Africa. The book became that year’s bestseller; it was so much in demand that the publishers could not print copies fast enough. King Solomon’s Mines was scribbled hurriedly as a result of a five-shilling wager that he could write a book half as good as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Presumably he won the wager, and the book earned him a knighthood. So good was the book that its success continued well beyond the century, and it is still remarkably popular today. It even created a new literary genre known as the ‘Lost World’, one that would inspire the creators of my boyhood literary heroes: Edgar Rice Burroughs, Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling and HP Lovecraft. Haggard’s book became the subject and title of a Hollywood film, not once but six times, and has heavily influenced blockbuster movies such as the Indiana Jones series.

The story of King Solomon’s Mines is a classic Victorian adventure about a journey into the uncharted swathes of Africa. The main character, Allan Quatermain, two friends and a couple of servants embark on an epic adventure into the unknown hinterland of southern Africa, which leads them across a great desert, where they almost die of thirst, into an isolated fertile valley inhabited by a disconnected Zulu tribe. The tribe is ruled by an evil pretender to the throne who wants to kill the party, which somehow survives. There’s the usual fictional stuff involving clandestine intrigue, a bloody battle, a love scene and a happy ending for the maligned tribe. But then the story gets really interesting.

The intrepid Europeans discover, and follow, a distinctively paved ancient road. After three days of travelling along it, it terminates at the remains of a diamond and gold mine. Beyond it the explorers find the mouth of a great cave and therein they discover a subterranean vault full of diamonds, ivory and gold coins “of a shape that none of us had seen before, and with what looked like Hebrew characters stamped upon them”. The story has another imaginative twist or two before the travellers return safely home.

Ostensibly, Farini’s Through the Kalahari Desert, which hit the shelves six months later, is the non-fiction version of Haggard’s great novel. There are many parallels: crossing the desert, almost dying of thirst, hunting, meeting strange tribes and having countless adventures. As in King Solomon’s Mines, there’s even an unrequited love vignette with the daughter of the local baKgalagadi chief at Lehututu, and of course great relics “of a glorious past”.

Farini’s name aside, the legend of a lost city somewhere in Africa became so well known that, over the course of the next century and a bit, many adventurers went in search of it. I, of the modern era, joined their ranks. As a young boy I had read, with insatiable thirst, the adventures of Tarzan in which the feral lad often came across ruins of great cities from a distant past. The prolific number of Tarzan books by Edgar Rice Burroughs first appeared in the early part of the twentieth century and undoubtedly drew inspiration from King Solomon’s Mines, possibly from Farini’s book too. Burroughs was not alone. South Africa’s greatest short-story writer, Herman Charles Bosman, wrote a parody simply entitled Lost City, and later the South African best-selling author of historical fiction Wilbur Smith wrote a lengthy novel entitled The Sunbird, which details the discovery of an unknown ruined city deep in the Kalahari. So entrenched is the legend of a lost city that it has been enshrined in the garish architecture of South Africa’s famed holiday complex – the Palace of the Lost City at Sun City.

Surrounded as I was with such mythology, it was a given, in my literary subconscious at least, that there still existed a ruined city of mysterious origins somewhere in some forgotten corner of the Kalahari; an African Eldorado or Machu Picchu as yet undiscovered. Reading Paton’s non-fictional narrative about his quest to find Farini’s apparently real lost city brought it firmly into my consciousness. I became afflicted with ‘Kalahari fever’, a condition common to those who love to solve a good mystery. You can tell us apart from the common herd. We are the glazed-eyed wanderer, readers of dusty old books and maps who, on a whim, plunge into one of the most inhospitable places on Earth, emerging weeks or months later, haggard and with eyes even more glazed.

I would soon discover – once I understood this condition – that I was not alone. Many had sought out the Lost City. Some had taken their whole family along, while others had searched alone over the course of a lifetime. They either combed the timeless depths of quasi-legendary anecdotes, whispered rumours and tales, or they physically criss-crossed the entire Kalahari basin and beyond. The searchers included distinguished professors, government agents fired up by ideological slants, doctors, outlaws, prospectors, schoolteachers and housewives. The youngest searcher, at two years old, could barely walk; neither could the oldest, who was well into his eighties. As for me, there have been repeated forays. Between 2005 and 2015, I ventured into the desert a dozen or so times, occasionally alone (as in this expedition), but most often with my travelling companion and wife, Amanda. Sometimes I took along friends and family to make the search more festive and less intense, and once I even had a television crew in tow. In short, my search for Farini’s Lost City became an obsession – one that I could not shake.

When I set out on this quest a decade ago, I thought finding the Lost City would be easy. After all, in his paper to the Royal Geograhical Society, the august body that had provided a platform for luminaries of African exploration such as David Livingstone, Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke, Farini gave exact coordinates for the location of his ruins. He couldn’t have been more precise. I didn’t wonder why the ruins hadn’t ever been found there, or consider that those coordinates lay in a different location from where Farini wrote the word ‘ruins’ on his map. I even ignored the fact that Paton wrote: “Farini had no compass, no sextant, no mathematics; therefore no-one could rely on his observations.” The moment I saw those coordinates I, together with Amanda, rushed off into the Kalahari, destination 23½º South and 21½º East.