Читать книгу Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth - Adam Zamoyski - Страница 22

12 Victory and Legend

ОглавлениеBeaulieu had been replaced by the no less aged Field Marshal Dagobert von Würmser. He divided his army into three columns which moved out in July 1796. One, consisting of 18,000 men under General Quasdanovitch, marched down the western side of Lake Garda, aiming to take Brescia and cut Bonaparte off from Milan. Another, of 5,000 men under General Meszaros, came down the valley of the Brenta further east in order to distract the French, while Würmser himself with 24,000 marched down the eastern side of Lake Garda aiming for Verona, where it was planned that the three forces were to come together to defeat the French and relieve Mantua.1

Bonaparte, who had just under 40,000 men in total, would be overwhelmed unless he defeated the Austrian columns separately. He took a bold decision, ordering Sérurier to abandon the siege of Mantua and pulling all his forces out of Würmser’s path. Although this would allow the Austrian to relieve Mantua and add its garrison to his force, it gave Bonaparte the opportunity to concentrate enough men to rout Quasdanovitch, which he did at Lonato on 3 August, before turning about to face Würmser with a slight numerical superiority, at Castiglione on 5 August. In a classic manoeuvre, he encouraged Würmser to turn his right flank, then launched a powerful attack on his exposed centre which cut the Austrian army in two, forcing it into a disorderly retreat back to whence it had come. ‘There you have another campaign finished in five days,’ Bonaparte rounded off his report to the Directory, in which he grossly exaggerated the enemy’s losses.2

It had been a brilliant feat of arms, with Bonaparte exploiting his central position to great effect. It had also demonstrated the qualities specific to the French army which gave it such an edge over its enemies. The Austrian army operated like a machine, observing tested routines such as only marching for six hours in twenty-four. The French followed no rules. The poor or non-existent supply system obliged them to operate in self-contained divisions or smaller units that the land they moved through could support, which encouraged greater independence and flexibility, particularly when it came to timing and distance.

Over those five days, Bonaparte had ridden more than one horse to death as he darted about. Marmont had spent twenty-four hours in the saddle, followed by another fifteen after only three hours’ rest. Augereau’s division had covered eighty kilometres in thirty-six hours, in the August heat. Masséna noted that two-thirds of his men had no coats, waistcoats, shirts or breeches, and marched barefoot. When they complained of the lack of provisions, Bonaparte told them the only ones available were in the enemy camp.3

The French army was made up of individuals with minds of their own. Bonaparte’s new aide Józef Sułkowski noted their agility and ‘astonishing vigour’, and was struck by the fact that the French soldier would surrender when cornered on his own, but never in the company of his fellows, and would ‘go out to his death rather than face shame’. In some units, shirkers and cowards were hauled before ‘juries’ of elder comrades who would condemn them to being beaten on their bottoms and despised until they had redeemed themselves with acts of valour.4

‘The French soldier has an impulsive courage and a feeling of honour which make him capable of the greatest things,’ believed Bonaparte. ‘He judges the talent and the courage of his officers. He discusses the plan of campaign and all the military manoeuvres. He is capable of anything if he approves of the operations and esteems his leaders,’ and would march and fight on an empty stomach if he believed it would bring victory.5

Many observers of the campaign of 1796 commented on the almost festive spirit in which these men appeared to banter with death, singing on the march and laughing as they went into battle. ‘We were all very young,’ recalled Marmont, and ‘devoured by love of glory’. Their ambition was ‘noble and pure’, and they felt ‘a confidence without limit in [their] destiny’, along with a contagious spirit of adventure. ‘It was during this campaign that moral exaltation played the greatest part,’ reminisced an old grenadier.’6

Exceptional leadership also played a part. At Lonato, Bonaparte led the 32nd Demi-Brigade into withering enemy fire. After the battle he presented it with a new standard, embroidered with the words: ‘Battle of Lonato: I was confident, the brave 32nd was there!’ ‘It is astonishing what power one can exert over men with words,’ he later commented about the incident. He also knew when to be harsh. After Castiglione he demoted General Valette in front of his men for having abandoned his positions too soon and allowed his unit to retreat in disorder. He hailed another demi-brigade, the 18th, as it took up positions before battle with the words: ‘Valorous 18th, I know you: the enemy won’t hold in front of you!’ At Castiglione, Augereau had excelled himself leading troops into the mêlée. ‘That day was the finest in the life of that general,’ Bonaparte later commented. Masséna too had electrified his men with his blustering courage.7

The cost of these heroics had been heavy. By the end of the campaign, almost as many men were in hospitals as in the ranks. Some of the older officers were burnt out, and Bonaparte himself was exhausted. Yet there was no time for rest. Würmser had fallen back to where he could be resupplied, and would soon be in a position to attack again. Bonaparte’s only hope lay in forestalling him. ‘We are on campaign, my adorable love,’ he wrote to Josephine on 3 September, having set off up the valley of the Adige. ‘I am never far from you. Only at your side is there Happiness and life.’ The next day, at Roveredo, he defeated an Austrian force under Davidovitch barring his way and pressed on, forcing Davidovitch to fall back beyond Trento. Würmser instructed him to hold on there while he himself marched down the Brenta valley into Bonaparte’s rear, meaning to take him between two fires.8

Bonaparte guessed Würmser’s intentions. He left around 10,000 men under General Vaubois to keep Davidovitch bottled up, and with the rest of his force set off behind Würmser, who was now marching down the Brenta hoping to penetrate into the rear of the French, without realising that they were on his tail. On 7 September Augereau caught up with and routed Würmser’s rearguard at Primolano, capturing his supply train, then forged on, hardly pausing for rest. Bonaparte spent that night under the stars, ‘dying of hunger and lassitude’, having eaten nothing but a small piece of hard-tack offered him by a soldier. He did not get much sleep, as by two in the morning he was on the move again. Würmser was unable to deploy his forces as they marched down the valley, and the French were able to defeat his divisions singly at Bassano, taking 5,000 prisoners, thirty-five pieces of artillery and most of his baggage. Quasdanovitch veered east with part of the army and made for Trieste, while Würmser with the main body made a dash for Mantua, which he entered on 15 September with no more than 17,000 men. This brought the number of Austrians bottled up in the fortress to over 25,000, including some fine cavalry, whose horses would only serve to feed them. It had been a strategic disaster. Marmont was sent to Paris with the flags taken in those two weeks, to spread the fame of the Army of Italy and its commander.9

Not for a moment during those frantic days did Bonaparte forget his ‘adorable Josephine’, to whom he complained from Verona on 17 September that ‘I write to you very often my love, and you very seldom,’ announcing that he would be with her soon. ‘One of these nights your door will open with a jealous crash and I will be in your bed,’ he warned. ‘A thousand kisses, all over, all over.’ Two days later he was back in Milan, where they would spend the best part of a month.10

Quite how happy that month was is open to question. In a letter to Thérèse Tallien on 6 September Josephine admitted to being ‘very bored’. ‘I have the most loving husband it is possible to encounter,’ she wrote. ‘I cannot wish for anything. My wishes are his. He spends his days adoring me as though I were a goddess …’ She was evidently sexually tired of him; he complained that she made him feel as though they were a middle-aged couple in ‘the winter of life’. But he had little time to brood over it.11

His recent triumphs had resolved nothing: there was still a large enemy force in Mantua which he reckoned could hold out for months, and while Lombardy was relatively quiet there were stirrings in other parts of the peninsula. The King of Sardinia had disbanded his Piedmontese regiments, with the consequence that bands of former soldiers were threatening the French supply lines. ‘Rome is arming and encouraging fanaticism among the people,’ Bonaparte wrote to the Directory, ‘a coalition is building up against us on all sides, they are only waiting for the moment to act, and their action will be successful if the army of the Emperor is reinforced.’ He suggested that given the circumstances he should be allowed to make policy decisions. ‘You cannot attribute this to personal ambition,’ he assured them. ‘I have been honoured too much already and my health is so damaged that I feel I ought to request someone to replace me. I can no longer mount a horse. All I have left is courage, and that is not enough for a posting such as this.’12

The Austrians would try harder than ever to relieve Mantua, now that it contained such a large force. And they were in a better position to achieve their goal, since the two French armies operating in Germany had been beaten and had retreated across the Rhine, releasing more Austrian troops from that theatre. Bonaparte wrote to Würmser suggesting an honourable capitulation on humanitarian grounds: Mantua was surrounded by water and marshland, and large numbers on both sides were suffering from fever. Würmser refused and sat tight, knowing help was on its way (it was only by chance that General Dumas, commanding the siege, discovered that Würmser was being delivered messages in capsules hidden in their rectums by men disguised as civilians). By the end of October there was a fresh imperial army in position under a new commander, Field Marshal Baron Josef Alvinczy.13

All Bonaparte could muster against it were some 35,000 men, exhausted after eight months of almost continuous campaigning in extreme conditions. He had received reinforcements, but these only just made up for the 17,000 who had been killed, those invalided out, those in hospitals, and the deserters. The troops were also of increasingly dubious quality, as a result of a process of negative selection. ‘The soldiers are no longer the same,’ wrote Bonaparte’s brother Louis. ‘There is no more energy, no more fire in them … The bravest are all dead, those that remain can be easily counted.’ According to some estimates, only 18 per cent of the original complement were still in the ranks, and the proportion was probably lower among officers. ‘The Army of Italy, reduced to a handful of men, is exhausted,’ reported Bonaparte. ‘The heroes of Lodi, of Milesimo, of Castiglione and Bassano have died for their motherland or lie in hospital.’14

His dazzling successes had won him not only adulation but also a host of jealous rivals and enemies. Chief among these were the various civilians – commissioners, administrators and suppliers – in the wake of the army, whom he had been preventing from enriching themselves, and who were sending slanderous reports back to Paris, warning that he was intending to make himself King of Italy. A military setback at this point might prove fatal to him.

His forces were dispersed in bodies of about 5,000, with one around his headquarters at Verona, one at Brescia in the west and one at Bassano in the east, one besieging Mantua, another in reserve at Legnago and a smaller one in a forward position to the north at Trento. They were placed in such a manner that they could easily concentrate, but this time it was going to be more difficult to deal with the enemy piecemeal. The Austrians were on the move by the beginning of November 1796: Davidovitch pushed back Vaubois from Trento while Alvinczy, with the main force of some 29,000, marched down the Brenta and on 6 November forced Masséna’s division out of Bassano. Bonaparte rushed to Rivoli to arrest the retreat of Vaubois, which he did in inimitable style. He called out two units which had shown lack of mettle and announced that their standards would be inscribed with the words ‘These no longer belong to the Army of Italy!’ Many of the men wept, and, as he had anticipated, they would redeem themselves with acts of surpassing bravery a couple of days later.15

But Alvinczy was by now threatening the French centre at Verona. Bonaparte attempted to hold him off at Caldiero, but the already dispirited troops were subjected to a violent storm. Drenching rain was succeeded by volleys of hail. ‘This storm blew straight into their faces, the heavy rain hiding the enemy who was pounding them with artillery, while the wind blew away even their fuses and their bare feet slithered in the clay soil, lending them no support,’ in the words of Sułkowski. They trudged back in mournful silence.16

Bonaparte was down to around 17,000 men facing Alvinczy’s 23,000, and he was strategically blocked, with Verona at his back. ‘We may be on the eve of losing Italy,’ he warned the Directory. He decided to take a chance. Leaving a small force in position before Verona, on the night of 14 November he crossed the Adige under cover of darkness and marched east along its right bank, recrossed it at Ronco and, leaving Masséna to cover his own left flank and distract Alvinczy, made a dash for Arcole, where he meant to cross the river Alpone and move into Alvinczy’s rear at Villanova. This would have cut the Austrians’ line of communications and forced them to retreat into his arms. They were caught in a funnel between the mountains and the river Adige and had no other exit – and the different corps of a retreating army can be taken on and defeated individually, in this case as they tried to cross the Alpone at Villanova.17

Everything went smoothly until the French spearhead came in sight of the small town of Arcole on the opposite bank of the Alpone across a thirty-metre-long straight wooden bridge resting on stone piles. It was defended by two battalions of Croat infantry numbering around 2,000 men with several field guns positioned so as to sweep not only the bridge, but the access to it on a dyke raised above the marshy floodplain.18

Bonaparte was in a hurry. He ordered General Verdier to storm the bridge, but his men came under withering fire before they got anywhere near it. He despatched a force to cross the river further south and threaten the defenders’ flank, but persisted in trying to cross the bridge. News had reached him that Alvinczy had perceived the threat to his rear and abandoned Verona. Masséna could distract him for a time, but if the Austrians crossed the Alpone at Villanova before Bonaparte could do so at Arcole, his plan would have failed and the French position would be critical once more.

Augereau and then Lannes attempted to lead the troops to the bridge, without success. Then Bonaparte dismounted and seized a flag. He challenged the men to show they were still the heroes of Lodi, but they would not follow him, even when he moved forward, accompanied by his aides and a small group of soldiers. Having covered a short distance and still a couple of hundred metres from the bridge, they were met by a volley which killed several around Bonaparte, including his aide Muiron. They rushed for cover, knocking Bonaparte off the dyke and into a drainage ditch where he landed up to his neck in water. He was eventually dragged out of it, but there could no longer be any question of taking the bridge.19

That evening, 15 November, he withdrew and recrossed the Adige. Although his initial plan had failed, he had nevertheless positioned himself in such a way that he now paralysed Alvinczy: if the Austrian moved west, Bonaparte could strike in his rear, and if he moved east he had to abandon hope of linking up with Davidovitch to achieve his objective of relieving Mantua. On the night of 16 November Bonaparte learned that Vaubois had been overwhelmed by Davidovitch, which opened the possibility of the two Austrian armies joining forces. The only way of preventing this was to threaten Alvinczy’s rear. Bonaparte had a bridge built over the Alpone downstream of Arcole and ordered Augereau to cross it while Masséna moved against Arcole, and despatched another force along the Adige to cross it further east to threaten Alvinczy’s communications. The ploy worked, and Alvinczy fell back on Villanova. This allowed Bonaparte to detach troops and send them to head off Davidovitch and force him back up to Trento. Alvinczy, who had moved west again to assist Davidovitch, now gave up and retired up the Brenta valley. He had lost many men and had failed in his purpose to liberate Würmser from Mantua.

The two-week campaign had been a messy, close-run business with no set-piece battle to present to the French public as grand spectacle. It was therefore necessary to fabricate one. In his despatch to the Directory, Bonaparte announced that the battle of Arcole had decided the fate of Italy. He grossly exaggerated Austrian losses while diminishing his own, and presented an account of derring-do to flatter French national pride. The captured flags were borne to Paris by Le Marois, who at the public ceremony in which they were handed over made a speech portraying Bonaparte tracing the path to victory, flag in hand, conveying the notion that he had stormed the bridge. In no time a print appeared in Paris depicting Bonaparte and Augereau leading the troops across it on horseback, each clutching a banner, succeeded by another showing Bonaparte on foot, brandishing the flag and encouraging his troops to follow him.20

For centuries kings and commanders had had their deeds immortalised in painting out of a mixture of vanity and political assertiveness. The Revolution had created a thirst for information among the illiterate which was satisfied by crude allegorical depiction, and this led to an explosion of semi-sacral illustration in praise of the nation, its leaders and its martyrs. Generals were depicted in heroic poses, and there were engravings of commanders such as Hoche and Moreau in circulation before any image of Bonaparte.21

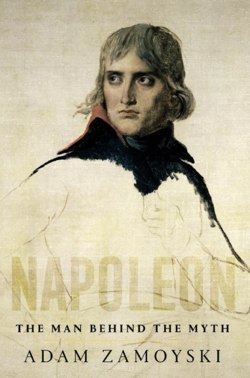

But he took propaganda to new levels. His mendacious despatches to the Directory, excerpts from which were printed and even plastered on walls for the public to read, were dramatic and exciting. The hyperbolic language of the Revolution in which they were couched created a subliminal sense of the supernatural, of the miraculous, of an adventure being enacted by men who appeared as superhuman as the heroes of the Iliad. Poets, playwrights and hacks of every sort saw in this excellent raw material for their own craft, and their works added to the concert of myth-making verbiage. This was accompanied by an iconography to suit, and between the moment he took command of the Army of Italy in 1796 and the end of 1798, no fewer than thirty-seven different prints of Bonaparte appeared on the market, some commissioned, some spontaneous, some based on actual representations of him, others giving him entirely imagined features, but all representing him as a hero.22

The propaganda surrounding Arcole saved Bonaparte’s position, but it could do little to assuage the pain inflicted by Josephine. ‘At last, my adorable Josephine, I am coming back to myself, death no longer stares me in the face,’ he had written with understandable relief the day after the fiasco of Arcole. Back in Verona two days later, he wrote her a tender note just before going to bed, reproving her as usual for not writing. ‘Don’t you know that without you, without your heart, without your love there can be no happiness of life for your husband,’ he wrote, going on to say how he longed to touch her shoulder, hold her firm breast and to plunge into her ‘little black forest’. ‘To live in Josephine is to live in Elysium. To kiss her, on the mouth, the eyes, the shoulder, the breast, all over, all over!’ Two days after that, having heard nothing, he wrote in teasing vein: ‘I don’t love you at all any more, on the contrary I hate you.’ He asked her what occupied her days so fully to prevent her from writing. ‘Who can it be, this wonderful and new love who absorbs all your time, tyrannises your days and prevents you from caring for your husband? Take care, Josephine, one of these nights your door will be forced and I will be in your bed. You know! The little dagger of Othello!’ He then reverts to a more loving tone and looks forward to being in her arms again and planting a kiss on her ‘little rascal’.23

He reached Milan panting with love on 27 November, only to find that she had gone to Genoa (with Lieutenant Charles). His disappointment and bitterness are given full expression in a note dashed off to her that evening and a letter the following day. ‘Farewell, adorable woman, farewell, my Josephine,’ he ended. General Henry-Jacques Clarke, who arrived from Paris the next day, found Bonaparte ‘haggard, thin, all skin and bone, his eyes sparkling feverishly’.24

Clarke had been sent by the Directory with the ostensible mission of opening negotiations with the Austrians, but in fact to spy and report on the commander of the Army of Italy. He was pleasantly surprised when Bonaparte agreed that negotiations with Austria were in order. Bonaparte knew that having driven back the French in Germany, Austria was about to launch an all-out offensive in Italy and would not be inclined to negotiate. But he had to gain Clarke’s support, so he set out to charm him. In little over a week, Clarke was assuring the Directory that ‘There is nobody here who does not regard him as a man of genius …’ He praised the general’s judgement, his authority and his efficiency. ‘I believe him to be committed to the Republic, and without any ambition other than that of conserving the glory which he has acquired for himself,’ he followed this up.25

Clarke’s support was an important asset in Bonaparte’s long-running battle with the other arm of the Directory’s control – its commissioners. Their brief had varied with unfolding events: lured by the cash and spoils he sent back, the Directory charged them with political and financial control of the occupied territories, but with the discovery earlier that year that General Pichegru commanding the Army of the Rhine and Moselle had been plotting with the enemy, their brief had been extended to surveillance of the military. They rode about in civilian dress with tricolour sashes and plumes that gave them the aspect of high-ranking commanders, often overruling officers.

In Saliceti, Bonaparte had at his side a man who for all his venality and opportunism was someone he could work with. The other commissioner, Pierre-Anselme Garrau, an unprepossessing hunchback with a virulently Jacobin background, was a thorn in his side. Soon after the conclusion of the armistice at Cherasco, Bonaparte had received instructions from the Directory that diplomatic negotiations were the preserve of the commissioners, not the army commander. He had by then concluded an armistice with the kingdom of Naples, and was negotiating with envoys of the Pope.26

He left these negotiations to the two commissioners, who allowed themselves to be drawn into labyrinthine discussions which withered fruitless after three months. Worse, Garrau had inadvertedly revealed Bonaparte’s plan to surprise and capture British ships in Livorno, allowing them to get away. Bonaparte had for some time been informing the Directory of the commissioners’ incompetence and reporting the venality and scandalous behaviour of the civil functionaries operating in Italy. In July, after Saliceti was transferred to supervise the French reoccupation of Corsica, Bonaparte set about destroying Garrau. He forbade him to give orders to soldiers while bombarding him with demands for supplies and blaming him for every shortage. Bonaparte appointed his own officers to rule the occupied territories and began eliminating the ‘shameless scoundrels’, as he termed the officials following in the wake of the army, replacing them with equally venal ones who owed everything to him. Such usurpation of the Directory’s authority could end badly for Bonaparte, and the matter had reached a climax in November, at the time of the Arcole campaign. He needed to watch his back.27

In October, he ordered the arrest in Livorno of a Corsican by the name of Panattieri, the man Paoli had sent to search the Buonaparte house in Ajaccio in 1793 and bring all the papers he could find to Corte. At Bonaparte’s request, all the papers in Panattieri’s possession were seized. Meanwhile Joseph, who had gone to Corsica as soon as the British had evacuated it in order to secure the remains of the Buonaparte estate and see what could be added to it as a result of the flight of the pro-British Corsicans, scoured archives in Ajaccio and Corte. It was the first step in what was to be a methodical editing of the Buonaparte brothers’ activities on the island.28

In the context, the arrival of Clarke proved fortuitous: his glowing reports of Bonaparte’s ability and devotion to the Republic persuaded the Directors that it was best to retreat. On 6 December 1796, they abolished the role of commissioners altogether.

Meanwhile, Josephine had returned to Milan and a semblance of harmony was restored. She gave a ball on 10 December at which the couple presided in regal manner. Although he had a low opinion of Italians, considering them to be lazy and effeminate, morally defective and politically immature, Bonaparte went along with the wishes of the Milanese intellectual elites for an independent Italian republic. Pre-empting any hopes the Directory might still entertain of using Lombardy as a bargaining counter, on 27 December he announced the creation of the Cispadane Republic (covering the nearside of the river Po, Padus in Latin). It was given an armed force made up of Poles forcibly enlisted by the Austrians who had either deserted or been taken prisoner, under the command of General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski.

At the beginning of January 1797 the Austrians were on the move once more, Alvinczy marching down the valley of the Adige while two other corps swept down the valley of the Brenta to relieve Mantua. Leaving only a small force to parry these, Bonaparte collected all the troops he could muster and on the night of 13 January made a rapid march up to Rivoli, where Joubert was attempting to stem Alvinczy’s advance. He arrived at two o’clock in the morning and quickly took in the situation. Alvinczy had split his force into six columns, and Bonaparte set about them separately, defeating one after the other. By late afternoon Alvinczy was in full retreat. This was turned into a rout by the intervention of Murat on his flank, and the Austrians fled, leaving behind nearly 3,500 dead and wounded and 8,000 prisoners, representing 43 per cent of Alvinczy’s total effectives.

This obviated the need for pursuit, which was as well, since late that afternoon Bonaparte received news that one of the Austrian prongs to the south, under General Provera, had broken through and was close to Mantua. He ordered Masséna to gather up his exhausted troops and dashed south. On 16 January, while Colonel Victor contained a sortie from Mantua by Würmser, Bonaparte directed Augereau’s division against Provera at La Favorita outside the city, forcing him to surrender. It was an extraordinary result: in the space of less than four days he had depleted the Austrian forces by more than half. In the space of the week the French had taken 23,000 prisoners, sixty guns and twenty-four flags. With all hope of relief dissipated, Würmser would surrender Mantua and its garrison of 30,000 men, half of them too sick to walk, on 2 February, giving Bonaparte another twenty standards to send back to Paris. The victory had been achieved through extraordinary exertion – Masséna’s corps had fought at Verona on 13 January, at Rivoli the following day and outside Mantua two days later, covering ninety-odd kilometres in the process.

Bonaparte did not need to wait for the surrender of Mantua to know how complete his triumph was, and on 17 January he wrote to the Directors announcing that in the space of ‘three or four days’ he had destroyed his fifth imperial army. ‘I’ve beaten the enemy,’ he wrote to Josephine that evening. ‘I am dead tired. I beg you to leave immediately for Verona. I need you, because I think I am going to be very ill. A thousand kisses. I am in bed.’29

She did come, but there could be no question of a long rest. Austria would not admit defeat and was mobilising a new force. It was also negotiating with the Vatican and the kingdom of Naples, which had a sizeable army. The Directory had long before ordered Bonaparte to overthrow the papacy, which it regarded as the source of all obscurantism in the world and the avowed enemy of the French Republic. Bonaparte felt no animus against the Church and treated the clergy in the lands he occupied with respect, if only out of calculation. But he despised Pius VI, whom he regarded as a treacherous opportunist ready to stir against him every time the Austrians looked as though they might be winning. He was also short of cash, both for his army and to send back to France to placate his political masters, and there was no shortage of that to be found in Rome.

With 8,000 men, some of them Italian auxiliaries, he entered Bologna, where on 1 February he declared war on the Pope. He defeated a contingent of papal troops at Imola and took possession of Ancona. He had a cold and was depressed by the farcical nature of ‘this nasty little war’, as he wrote to Josephine on 10 February. Confronted by badly led mercenaries and displays of religious fanaticism, at Faenza he rounded up all the monks and priests of the place to lecture them about true Christian values.30

The Pope sent a delegation to negotiate, but the honey-voiced prelates who had been so successful with Garrau were no match for a bullying Bonaparte. By the Treaty of Tolentino, signed on 19 February, Pius ceded the former papal fiefs in France, Avignon and the Comtat Venaisin, the Legations of Bologna, Ferrara and Romagna, along with Ancona. He also agreed to close his ports to British ships, and undertook to pay 30 million francs and deliver a number of works of art and manuscripts.

Five days later Bonaparte was back in Bologna with Josephine, who accompanied him to Mantua, where he prepared for the next campaign. The Directory had accepted that only he was capable of beating the Austrians decisively, and reversed its policy of treating the Italian theatre as a diversion. It transferred two strong divisions from the northern theatre, under generals Delmas and Bernadotte, reinforcing Bonaparte significantly: he could field 60,000 men while leaving 20,000 guarding his rear. This made him undertake what was under any circumstances a daring enterprise – a march on Vienna.

Three Austrian forces stood in his way, one under Davidovitch at Trento, another blocking the valley of the Brenta, and the main force concentrated along the river Tagliamento. They were under the overall command of Archduke Charles of Austria, a capable general two years younger than Bonaparte who had defeated the French in Germany. His presence was helping to restore the morale of the Austrian troops, and Bonaparte decided not to give him time. On 10 March he went into action, forcing Davidovitch up the valley of the Adige towards Brixen while Masséna advanced up the Brenta and Bonaparte took on the archduke himself on the Tagliamento. He breached his defences and forced him to fall back on Gratz (Gorizia) and Laybach (Lubljana). By then two of the passes were in French hands, and the archduke had to beat a hasty retreat if he were not to be cut off as Bonaparte reached Klagenfurt, on 30 March.

He was now poised to advance on Vienna, but if he did so, the Austrian armies in Germany could sweep into his rear. Behind him lay the whole of Italy guarded by a mere 20,000 men. Anti-French feeling simmered throughout the peninsula, with Naples, Venice, the papacy, Parma and Modena only waiting for a chance to strike. His army had advanced so far that it was running out of supplies, and the rocky region in which it now found itself would not sustain it for long. He therefore had to conclude peace urgently.

The one thing that would convince Austria to give in was a French advance across the Rhine by Moreau and Hoche, who had taken over from Pichegru, and Bonaparte sent request after request to the Directory urging it to order one. But he had learned to rely only on his own resources. On 31 March he offered Archduke Charles an armistice, but pressed on swiftly, reaching Leoben and taking the Semmering pass, less than a hundred kilometres from Vienna. There was panic in the Austrian capital, with people packing their valuables and leaving for places of safety. But with no support from Moreau and Hoche, Bonaparte could not afford to go any further. On 18 April preliminaries of peace were signed at Leoben.

Bonaparte had no right to negotiate a peace, let alone one which redrew the map as drastically as this one. The terms were that Austria ceded Belgium to France, gave up its claim to Lombardy and recognised the Cispadane Republic. In return, Austria was to receive part of the territory of the Republic of Venice.

Venice had remained neutral throughout the conflict, but French and Austrian armies had operated on its territory, using cities such as Verona and Bassano as military bases. Their depredations had provoked reprisals against French soldiers, and on 7 April Bonaparte had sent Junot to Venice with an insulting ultimatum to its government to stop them. When the Venetian authorities sent envoys to Bonaparte he lambasted them and declared that he would act like Attila if they did not submit. On 17 April there was a riot in Verona, almost certainly provoked on his orders, in the course of which some French soldiers were killed. He responded by making fresh demands of the Venetian government, insisting it reform its constitution along French lines. Provocations on either side ratcheted up the conflict, and a French vessel was fired on from one of the Venetian forts. On 1 May Bonaparte declared war on Venice and sent in troops. A puppet government was set up and instructed to settle with Austria the cession of territory, for which Venice was to be compensated with the former papal province of the Legations. Meanwhile, the plunder of the city’s treasures began and the horses of St Mark’s were removed to Paris.31

Such treatment of a neutral sovereign state was nothing new for Austria, which had joined in the partitions of Poland and had long been eyeing Venetian territory, with its access to the sea. But for the French Republic, the liberator of oppressed peoples, to act in such a way was shocking, and when they heard of it the members of the Directory were incensed. Clarke, who reached Leoben two days after the signature, was aghast. But Bonaparte had already sent Masséna to Paris with the document and an accompanying letter in which he listed the advantages for France of the agreement, which he termed ‘a monument to the glory of the French Republic’. He went on to state that if the Directory did not accept the terms of the peace, he would be content to resign his post and pursue a civilian career with the same determination and single-mindedness as he had his military one – a clear threat that he would go into politics. There was nothing the Directory could do: news of the signature of peace had been greeted ecstatically throughout France, with celebrations in some towns lasting three days.32