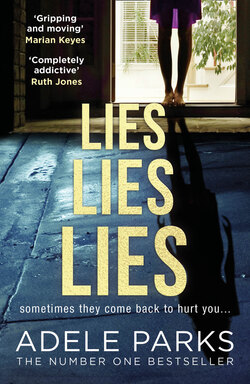

Читать книгу Lies Lies Lies - Adele Parks, Adele Parks - Страница 27

Оглавление12

Chapter 12, Simon

Wednesday, 13th July 2016

The TV woke him up. He tried to focus, but it was tricky. There were a lot of voices talking across one another. What was he watching? Four middle-aged women, sitting on stools around a breakfast bar. They were wearing bright tops, but the gaiety was cancelled out by their angry faces. They were arguing although not with each other. Simon listened for a moment or two, long enough to gather they were angry with some man, or some male thing, yet there were no men there to shout at so they were shouting at each other and in general. It was almost funny.

He knew what it was, he knew it. Daisy loved this show. It was Loose Women. He didn’t know how he knew that, he was hardly the target audience, but he did. He felt remembering the name of the show was something. A small victory. Daisy sometimes watched it in the school holidays. A guilty pleasure when she was ironing or doing something with Millie, crafting or whatever. It must be mid-morning. Why was he asleep in an armchair mid-morning? His head was fucking killing him. It was pulsing, pounding. He must be ill. That was it. He was off work because he was ill. He searched about for the remote control and noticed an empty bottle of red wine and an empty bottle of whisky at his feet. He ignored them. They didn’t make sense. Finding the remote was all that mattered. He had to mute the angry women. If only life was as easy. Unfortunately, even when he managed to shut them up, the screaming and yelling continued in his head. He didn’t know if it was real, or something he remembered, or just something he was imagining. It was sometimes hard to tell.

Simon looked out of the window, it was pitch black, dead of night, not mid-morning. He turned back to the TV confused. Definitely Loose Women. It took longer than it should but then he took a stab at sorting it out in his mind – it had to be a late night repeat. He checked his watch; it was tricky to focus, he couldn’t quite see the illuminated numbers. He was really ill. Maybe hallucinating, a fever? He’d heard something was going around, something serious. It was 3.15 a.m. Or maybe 5.15 a.m. He didn’t know or care. Not really. What was that smell? It was disgusting. Puke and sweat.

He noticed that his shirt and the arm of the chair were covered in vomit. Some of it had solidified, some of it still oozed. Sloppy and shaming. He peeled off his shirt, balled it up, tried not to let the puke slide onto the floor. He walked through to the kitchen and dropped the soiled garment on the floor, in front of the kitchen sink. He realised that he probably should put it in the washing machine, but he couldn’t, not right then. Too much effort. He wasn’t up to it. He was ill. Daisy would sort it out when she got up. He tried to remember yesterday. Had he come home from work sick? Had he gone into work at all? Maybe this was not a bug, maybe he’d had a few jars, eaten a curry with a bad prawn. He couldn’t remember eating. The puke didn’t smell of curries or prawns.

He needed a drink. Water maybe? No, a beer. A beer would be best. Hair of the dog. Because yes, he realised now this was most likely a hangover. Off the scale, a different level, but a hangover all the same. His hands were freezing, his vision was blurred. Not a hangover then, he was still drunk. It would be best to keep on drinking.

As he opened the fridge, the light spilt out on to the kitchen and he nearly dropped the bottle in shock.

‘What the fuck are you doing, sitting in the dark?’ he yelled.

Daisy sighed. She’d been crying. He could tell. Her eyes were bloodshot and her face blotchy. Simon realised, with a slow sense of regret, that it had not just been a late night but an emotional one, too.

Here it was. Off they went.

‘I stayed up to check you didn’t choke on your own vomit,’ she said with another sigh. Like, how was it possible to have that much air and disappointment to expunge? It couldn’t be for real, could it. There had to be an element of theatre to it, a sense of drama. She had her hands wrapped around a mug, the very picture of wifely patience. It fucked him off. Her patience – or at least her show of it – her acceptance, her constant understanding, it all fucked him off. Because it wasn’t real. It wasn’t her. He didn’t believe it. Not anymore. It would be more real if she showed she was angry. He wanted her to be angry. Like him.

He was swaying, ever so slightly. He needed to sit down. Just as he was about to do so, his body collapsed below him. He sent a wooden kitchen chair toppling, his head thumped against the corner of a unit. The pain was blunted by his state, but in the morning there would be a bump. His body relaxed into the pain, working through it. He’d learnt this technique now. Sometimes when he was drinking he hurt himself by accident. One evening, he fell down some steps in town, another time he walked into the closed patio doors thinking they were open. It was best to roll with the pain. Not to fight it.

‘Oh Simon.’ He could hear pity and despair in Daisy’s voice.

He felt warm and then cold, his thighs. He could smell something beneath the puke and sweat. It was a dark and acidic smell. It was piss. He’d pissed himself.

He woke up, he was in bed. He was relieved. Sometimes, he didn’t get to bed. He fell to sleep on a chair in the sitting room, on a bench in the street, or on the train home. That was the worst. He’d be carried to the last stop on the route and then woken up by a ticket inspector. He couldn’t always get an Uber. Occasionally he’d slept on stations, caught the first train home in the morning. Waking up in his own bed was a bonus. He put his fingers to the back of his head where it ached, not just the usual hangover ache, something more specific; there was a lump, but he couldn’t feel any stickiness, no blood. There weren’t any bottles next to his bed. He was naked but smelt clean. It didn’t add up.

Daisy was not in bed. As he sat up he noticed she was dozing on the chair in the corner of the bedroom, the one that was normally covered in discarded clothes. She heard him stir and her eyes sprung open. Always a light sleeper. Instantly, her face was awash with anxiety, resentment, disappointment.

‘Morning,’ Simon said brightly. Best to style this out. Clearly there had been something but as yet he couldn’t recall exactly what that something was, so he wasn’t worried. He was in his own bed, there wasn’t a bucket or any bottles by his side. He was good. ‘What time is it? I need to get to work.’ As he asked this, he swung his legs out of bed. The movement was too sudden, too energetic. He felt like crap. His body ached and shook but he was good at ignoring that, good at hiding how awful he felt, how awful he was.

Daisy checked her watch. ‘It’s noon, just after,’ she muttered tonelessly.

‘Why aren’t you at work?’

‘I took a personal day.’

Simon snorted. ‘Is that a thing now?’

She ignored his sarcasm. It was unusual for Daisy to take time off work, unprecedented actually. Simon was not sure he wanted to know why she’d done so. He asked the more pressing question instead, ‘Did you call my boss too?’ Simon calling in sick was not unprecedented and although Daisy didn’t like doing it for him – made a big fuss about how she hated lying – she had done so in the past. The truth was, she was a better liar than she made out.

‘You really can’t remember, can you?’ she asked.

‘Remember what?’

Another sigh, more of a puff. She really was honestly a tornado of regret and dissatisfaction. ‘You don’t have a job. You were fired yesterday.’

‘What the fu— What are you talking about? Fired? No.’

‘You turned up late and drunk, again. But this time you were aggressive with the client and it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Your boss has been looking for an excuse for a while. You know he has.’

She was wrong. She was being a bitch. Dramatic. ‘How do you know this?’ he demanded.

‘You didn’t tell me. Luke did.’

‘Oh, Saint Luke,’ Simon snapped, snidely.

‘I don’t know why you are being like that. He’s your best friend. I called him last night when you came home legless and making no sense. He filled me in on the details.’

Simon dropped his head into his hands and tried, really fucking hard, to remember what she was going on about. But he couldn’t. Nothing. Yesterday was nothing. The last thing he remembered was leaving home, catching the tube into Covent Garden. But he did that most days, he wasn’t sure if that was a specific memory or just something that he knew happened.

Daisy looked disbelieving. She thought his memory – or lack of it – was convenient, that he blanked out what he wanted. Right now, Simon thought the blackout was inconvenient. He wanted to know how and why he’d lost his job. Or at least, he probably wanted to know.

So, she told him. Her version, or Luke’s version, some bloody version but he couldn’t imagine it was the truth. He wasn’t drunk when he turned up at the office. Maybe, they could smell alcohol on his breath. Occasionally, he had a nip from his flask as he walked to the station. It was no big deal. Not drunk. And a nip in his coffee, too. Sometimes. Some people like maple syrup in their coffee, he liked whisky. It didn’t mean anything. It certainly wasn’t a dependency. What the hell? No. He was a creative, an interior designer, no one could expect him to work to a rigid schedule, he needed space. He needed freedom. Who puts a meeting in a diary at 10 a.m. anyway? It was uncivilised. And the client was a dick. OK, Simon could see that it wasn’t perhaps his wisest move, calling him the c-word for suggesting mushroom for the colour palette. Maybe that was hard to come back from. Simon didn’t really know why he had been so against mushroom, except he’d been thinking something brave, something bold. That’s what they pay him for, right? His ideas. Why wouldn’t they listen to him? He did not believe that he wasn’t able to stand up properly. They felt threatened. By him? That was just bullshit.

She made a big thing about saying she couldn’t account for his afternoon. Apparently, he stormed out of the agency or maybe security threw him out; she wasn’t totally clear on this point. Someone who knew that they were mates had called Luke, who had spent his afternoon looking for Simon. And that made him some sort of god in Daisy’s eyes. She kept going on about how good it was of him, how inconvenient. ‘He has a job of his own, you know, besides being your babysitter,’ she snapped bitterly. ‘Can you imagine how embarrassing it was for him? Since he’s the one that introduced the client to your firm in the first place. He is always putting work your way. If you ask me it’s the main reason the agency have kept you on as long as they have.’

‘That’s just bullshit. I’m good at what I do and they know it.’ Simon was sitting naked on the edge of the bed. His penis flaccid, his head is in his hands. What did this woman want from him? She was stripping away his manhood with her tongue. If what she was saying was true, he’d just lost his fucking job, how about some support please? Some sympathy. She told him that he came home at midnight, that he was ‘awkward’. He fell over in the kitchen and wouldn’t come to bed. He couldn’t remember any of this, but he believed her on that last point. He didn’t want to go to bed with Daisy. The thought was a hideous one. After what Martell had told him. Besides, sex is nothing compared to booze. Sex was messy and demanding, it came with secrets, never-articulated caveats and demands. It lied. Booze was pure. Generous. Easy.

‘You threw up on yourself. I stayed up all night, checking on you every thirty minutes to see you hadn’t choked,’ added Daisy. Simon tutted. Her martyrdom was boring. What did she want? A medal? ‘You peed yourself,’ she added, exasperated.

‘Then how come I’m clean now?’ Simon challenged. He couldn’t believe Daisy had dragged him upstairs if he was in the state she said he was.

‘I called Luke. He came around at four in the morning. He helped me get you upstairs and into the shower. We hosed you down.’

She was a lying bitch. He knew she was.