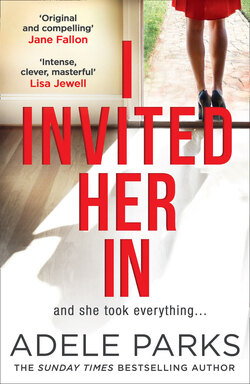

Читать книгу I Invited Her In - Adele Parks, Adele Parks - Страница 8

Оглавление1

Melanie

Monday 19th February

While the girls are cleaning their teeth I start to stack the dishwasher. It’s too full to take the breakfast pots – I should have put it on last night. There’s nothing I can do about this now, so I finish making up their packed lunches and then have a quick glance at my phone. I’m expecting an email from my area manager about the results of some interviews we held last week. I work in a high street fashion retailer that everyone knows. There’s one in every town. Our branch needs another sales assistant and, as assistant manager, I was asked to sit in on the interviews. Dozens of people applied; we interviewed six. I have a favourite and I’m crossing my fingers she’ll be selected. Unfortunately, I don’t get to make the final decision.

I skim through the endless offers to invest in counterintuitive home-protection units, or pills that promise me thicker and fuller hair or a thicker and fuller penis, and look for my boss’s name. Suddenly, I spot another name – ABIGAIL CURTIZ – and I’m stopped in my tracks. It jumps right out at me. Abigail Curtiz. My first thought is that it is most likely to be a clever way of spreading a virus; the name is a coincidence, one just plucked out of the air by whoever it is who is mindless enough, and yet clever enough, to go to the effort of sending spam emails to infect other people’s gadgets. But Curtiz with a z? I hesitate before opening it, as it’s probably just trouble. However, the email is entitled, ‘It’s Been Too Long’ which sounds real enough, feasible. It has been a long time. I can’t resist. I open it. My heart thumping.

Normally, I skim read everything. I have three kids and a job, my default setting is ‘hurried’, but this email I read carefully. ‘No!’ I gasp, out loud.

‘Bad news?’ asks Ben with concern. He’s moving around the kitchen, looking for something. His phone, probably. He’s always mislaying that and his car keys.

‘No, it’s not.’ Not exactly. ‘I’ve just got an email from an old friend of mine. She’s getting divorced.’

‘That’s sad. Who?’

‘Abigail Curtiz. Abi.’ Her name seems strange on my lips. I used to say it so often, with such pleasure. And then I stopped doing so. Stopped talking to her, stopped thinking about her. I had to.

Ben looks quizzical. He’s one of those good husbands who tries to keep up when I talk about my friends, but he doesn’t recall me mentioning an Abigail. That’s not a surprise. I never have.

‘We were at uni together,’ I explain, carefully.

‘Oh, really?’ He reaches for the plate of now-cold toast in the middle of the kitchen table and snatches up a piece. He takes a bite and, while still chewing, he kisses me on the forehead. ‘Right. Well, you can tell me about her later. Yeah?’ He’s almost out of the door. He calls up the stairs, ‘Liam, if you want a lift to the bus stop, you need to be downstairs five minutes ago.’ I smile, amused at his half-hearted effort at sounding like a ruthless disciplinarian, hellbent on time-keeping. He blows the facade completely when he comes back into the kitchen and asks, ‘Liam has had breakfast, right? I don’t like him going out on an empty stomach. I’ll wait if needs be.’

We listen for the slow clap of footsteps on the stairs and Liam lumbers into the kitchen right on cue. He grew taller than me four years ago, when he was just thirteen, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that he now towers above me, but it absolutely is. Every time I see him, I’m freshly startled by the mass of him. He’s broad, makes an effort to go to the gym and bulk out. He’s bigger than most boys his age. I wonder where my little boy went. Is he still buried somewhere within? Liam is taller than Ben now, too. Imogen, who is eight, and Lily, just six, are still wisps. They still scamper, hop, and float. When either of them jumps onto my knee, I barely register it.

I have to stretch up now, to steal a hug from Liam. I also have to judge when doing so is appropriate and acceptable. I try to get it right because it’s too painful to see him dodge my affection, which he sometimes does. He’s outgrown me. I must respect his boundaries and his privacy; I’m ever mindful of it but I can’t help but miss the little boy I could smother with kisses whenever the desire struck me. Now I wait for Liam’s rare but generous hugs, mostly contenting myself with high fives. Today he looks tired. I imagine he stayed up later than sensible last night, watching YouTube videos or playing games. When he’s docile, he’s often more open to care and attention. I take advantage, ruffle his hair. Even peck him on the cheek. He picks up two slices of toast from the plate I’m proffering. Shoving one into his mouth, almost in its entirety, unconcerned that it’s cold. He takes a moment to slather the second slice with jam. He’s always had a sweet tooth.

‘Thanks Mum, you’re the best.’

I don’t spoil the moment by telling him not to speak with his mouth full; there really are only so many times you can remind someone of this. He turns to his dad and playfully asks, ‘What are you waiting for? I’m ready.’

They’re out the door and in the car before I can ask if he has his football kit, whether he’s getting himself home from training this evening or hoping for a lift, whether he has money for the vending machine. It’s probably a good thing. Me fussing that way really irritates him. I usually try to limit myself to just one of those sorts of questions per morning. The girls, however, are still young enough to need, expect and even accept, a barrage of chivvying reminders. I check the kitchen clock and I’m surprised time has got away. I gulp down my tea and then shout up the stairs. ‘Girls, I need you down here pronto.’

As usual, Imogen responds immediately. I hear her frantic footsteps scampering above. She starts to yell, ‘Where is my hairbrush? Have you seen my Flower Fairy pencil case? Who moved my reading book? I left it here last night.’ She takes school very seriously and can’t stand the idea of being late.

Lily is harder to impregnate with any sense of urgency. She has picked up some of the vocabulary that Liam and his friends use – luckily nothing terrible yet, but she often tells her older siblings to ‘chill’ and she is indeed the embodiment of this verb.

I drop the girls off at school with three minutes to spare before the bell is due to ring. I see this as a bonus but honestly, if they’re a few minutes late I don’t sweat it. I only make an effort with time-keeping because I know Imogen gets stressed and bossy otherwise. I’m aware that it’s our duty as parents to instil into our children a sense of responsibility and an awareness of the value of other people’s time, but really, would the world shudder if they missed the start of assembly?

I wasn’t always this relaxed. With Liam, I was a fascist about time-keeping. About that, and so much more. I liked him to finish everything on his plate, I was fanatical about him saying please and thank you and sending notes when he received gifts. Well, not notes as such, because I’m talking about a time before he could write. I got him to draw thank you pictures. His shoes always shone, his hair was combed, he had the absolutely correct kit and equipment. I didn’t want him to be judged and found lacking. It’s different when you’re a single mum, which I was with Liam. I met Ben when Liam was almost six. Being married to Ben gives me a confidence that allows me to believe I can be two minutes late for school drop-off and no one will tut or roll their eyes. I didn’t have the same luxury when Liam was small.

Suddenly I think about Abigail Curtiz’s email and I’m awash with conflicting emotions.

There are lots of things that are tough about being a single parent. The emotional, physical, and financial strain of being entirely responsible for absolutely everything – around the clock, a relentless twenty-four/seven – takes its toll. And the loneliness? The brutal, crushing, insistent loneliness? Well, that’s a horror. As is the bone-weary, mind-wiping, unremitting exhaustion. Sometimes my arms ached with holding him, or my back or legs. Sometimes, I was so tired I wasn’t sure where I was aching; I just felt pain. But there were moments of reprieve when I didn’t feel judged, or lonely, or responsible. There were moments of kindness. And those moments are unimaginably important and utterly unforgettable. They’re imprinted on my brain and heart. Every one of them.

Abigail Curtiz owns one such moment.

When I told Abi that I was pregnant she was, obviously, all wide eyes and concerned. Shocked. Yes, I admit she was bubbling a bit, with the drama of it all. That was not her fault – we were only nineteen and I didn’t know how to react appropriately, so how could I expect her to know? We were both a little giddy.

‘How far on are you?’ she asked.

‘I think about two months.’ I later discovered at that point I was officially ten weeks pregnant, because of the whole “calculate from the day you started your last period” thing, but that catch-all calculation never really washed with me because I knew the exact date I’d conceived. Wednesday, the first week of the first term, my second year at university. Stupidly, I’d had unprotected sex right slap-bang in the middle of my cycle. That – combined with my youth – meant that one transgression was enough. And even now, a lifetime on, I feel the need to say it wasn’t like I made a habit out of doing that sort of thing. In all my days, I’ve had irresponsible, unprotected sex precisely once.

‘Then there’s still time. You could abort,’ Abigail had said simply. She did not shy away from the word. We were young. The power, vulnerability and complexity of our sexuality was embryonic, but our feminist rights were forefront of our minds. My body, my choice, my right. A young, independent woman, I didn’t have to be saddled with the lifetime consequences of one night’s mistake. There had been a girl on my course who’d had a scare in the first year. I’d been verbose about her right to choose and I’d been clear that I thought she should terminate the pregnancy, rather than her education. The girl in question had agreed; so had Abi and pretty much everyone who knew of the matter. She hadn’t been pregnant, though. So. Well, you know, talk is cheap, isn’t it? She’s the chief financial officer of one of the biggest international Fast-Moving Consumer Goods corporations now. I saw her pop up on Facebook a couple of years ago. CFO of an FMCG. I Googled the acronyms. She accepted my friend request, which was nice of her, but she rarely posts. Too busy, I suppose. Anyway, I digress.

I remember looking Abi in the eye and saying, ‘No. No, I can’t abort.’

‘You’re going ahead with it?’ Her eyes were big and unblinking.

‘Yes.’ It was the only thing I was certain of. I already loved the baby. It had taken me by surprise but it was a fact.

‘And will you put it up for adoption or keep it?’

‘I’m keeping my baby.’ We both sort of had to suppress a shocked snigger at that, because it was impossible not to think of Madonna. That song came out when I was about five years old but it was iconic enough to be something that was sung in innocence throughout our childhoods. The tune hung, incongruously, in the air. It wasn’t until a couple of years later that the irony hit me: an anthem of my youth basically heralded the end to exactly that.

‘OK then,’ she said, ‘you’re keeping your baby.’

Abigail instantly accepted my decision to have my baby and that was a kindness. An unimaginably important and utterly unforgettable kindness.

She didn’t argue that there were easier ways, that I had choices, the way many of my other friends subsequently did. Nor did she suggest that I might be lucky and lose it, the way a guy in my tutorial later darkly muttered. I know he behaved like an arsehole because before I’d got pregnant, he’d once clumsily come on to me one night in the student bar. I was having none of it. I guess he had mixed feelings about me being knocked up, torn between, ‘Ha, serves the bitch, right’ and ‘So, she does put out. Why not with me?’ I tell you, there’s a lot of press about the wrath of a woman scorned, but men can be pretty vengeful, too. Anyway, back to Abi: she did not fume that I was being romantic and short-sighted, the way my very frustrated tutor did when I finally fessed up to her, and nor did she cry for a month, the way my mother did. Which was, you know, awful.

She made us both a cup of tea, even went back to her room to dig out a packet of Hobnobs, kept for special occasions only. I was on my third Hobnob (already eating for two) before she asked, ‘So who is the dad?’ Which was awkward.

‘I’d rather not say,’ I mumbled.

‘That ugly, is he?’ she commented with a smile. Again, I wanted to chortle; I knew it was inappropriate. I mean, I was pregnant! But at the same time, I was nineteen and Abi was funny. ‘I didn’t even know that you were having sex with anyone,’ she added.

‘I didn’t feel the need to put out a public announcement.’

Abigail then burst into peels of girlish, hysterical giggling. ‘The thing is, you’ve done exactly that.’

‘I suppose I have.’ I gave in to a full-on cackle. It was probably the hormones.

‘It’s like, soon you are going to be carrying a great big placard saying, I’m sexually active.’

‘And careless,’ I added. We couldn’t get our breath now, we were laughing so hard.

‘Plus, a bit of a slag, cos you’re not sure who the daddy is.’

I playfully punched her in the arm. ‘I do know.’

‘Of course you do, but if you don’t tell people who he is, that’s what they’re going to say.’ She didn’t say it meanly, it was just an observation.

‘Even if I tell them who the father is, they’ll call me a slag anyway.’ Suddenly, it was like this was the funniest thing ever. We were bent double laughing. Which was odd, since I’d spent most of my teens carefully walking the misogynistic tightrope, avoiding being labelled a slag or frigid, and I’d actually been doing quite a good job of balancing. Until then. It really wasn’t very funny. The laughter was down to panic, probably.

The bedrooms in our student flat were tiny. When chatting, we habitually sat on the skinny single beds because the only alternative was a hard-backed chair that was closely associated with late-night cramming at the desk. The room that was supposed to be a sitting room had been converted into another bedroom so that we could split the rent between six, rather than five. We collapsed back onto the bed. Lying flat now to stretch out our stomachs that were cramped with hilarity and full of biscuits – and in my case, baby. I looked at my best friend and felt pure love. We were in our second year at uni; it felt like we’d known one another a lifetime. Uni friendships are more intense than any other. You live, study and party together, without the omniscient, omnipresent parental influence. Uni friends are sort of friends and family rolled into one.

Abi and I met in the student union bar the very first night at Birmingham University. Although I would not describe myself as the life and soul of the party I wasn’t a particularly shy type either; I’d already managed to strike up a conversation with a couple of geology students and while it wasn’t the most riveting dialogue ever, I was getting by. Then, Abigail walked up to me. Out of nowhere. Tall, very slim, the sort of attractive that girls and Guardian-reading boys appreciate. She had dark, chin-length, sleek, bobbed hair with a heavy, confident fringe. She was all angles, like a desk lamp, and it seemed remarkable that she was poised to shine her spotlight on me. She shot out her hand in an assured and unfamiliar way. Waited for me to take it and shake it. In my experience, no one shook hands, except maybe men in business suits on the TV. My dad was a teacher; he sometimes wore a suit, but mostly he preferred chinos and a corduroy jacket. I suppose he must have occasionally shaken the hands of his pupils’ parents, but I’d never seen anyone my age shake anyone else’s hand. Her gesture exuded a huge level of jaunty individuality and somehow flagged a quirky no-nonsense approach to being alive. Her eyes were almost black. Unusual and striking.

‘Hi. I’m Abigail Curtiz, with a Z. Business management, three Bs. You?’

I appreciated her directness. It was a fact that most of the conversations I’d had up until that point hadn’t stumbled far past the obligatory exchange of this precise information.

‘Melanie Field. Economics and business management combined. AAB.’

‘Oh, clever clogs. Two degrees in one.’

‘I wouldn’t say—’

She cut me off. ‘That means you are literally twice as clever as I am.’ If she believed this to be true, it didn’t seem to bother her; she took a sip from her wine glass, winced at it.

‘Or half as focused,’ I said. I thought a self-deprecating quip was obligatory. Where I came from, no one liked a show-off. Being too big for your boots was frowned upon; getting above yourself was a hanging offence. Abi pulled a funny face that said she didn’t believe me for a moment; more, that she was a bit irritated that I’d tried to be overly modest.

‘OK, that’s the bullshit out of the way,’ she said with a jaded sigh. She didn’t even bother to introduce herself to the geology students. I glanced at them apologetically as she scoured the bar. ‘Who do you fancy?’ she demanded.

‘Him,’ I replied with a grin, pointing to a hot, hip-looking guy.

‘Come on then, let’s go and talk to him.’

‘Just like that?’ I know my face showed my astonishment.

‘Yes. I promise you, he’ll be more than grateful.’

She made me laugh. All the time. Her direct, irreverent tone never faltered, never flattened, not that evening or for the rest of the year. We did talk to the hot, hip guy; nothing came of it, I didn’t really want or expect it to, but it was fun. We spoke to him and maybe ten other people. It quickly became apparent that Abigail oozed cool self-belief; she thought the world was hers for the taking, and it was a fair assessment. She was charming and challenging, full of bonhomie and the sort of confidence that is doled out in private-school assemblies. The best bit was, she seemed happy for me to hitch along for the ride.

It was Abi who persuaded me to join the debating society and she was the one who insisted we went to the clubs in town, rather than just limit ourselves to the parties that bloomed in the university common rooms. She did all the student things like three-legged pub crawls and endless themed parties but she also insisted we did surprising stuff, like visit the city’s museums and art galleries. Some people whispered that she was pretentious; they resented the fact that she only enjoyed listening to music on vinyl and was fussy about the strength of coffee beans; she refused to drink beer, sticking exclusively to French red wine; she rarely ate. She was, by far, the most interesting person I’d ever met.

We became close. She wasn’t my only friend or even my best friend but she was my favourite. I sometimes found it a bit exhausting to keep up with her and while she signed up for the university’s dramatic society, I was content to sit in the audience and watch her play a shudderingly shocking Lady Macbeth. I joined her on the coach to London and protested outside Parliament over something or other – I forget what now – she waved her placard all day, whereas around noon, I slipped off to Oxford Street for a quick look around Topshop.

She was the first person I told about my pregnancy. By the time we’d munched our way through almost the entire packet of Hobnobs, Abi commented, ‘Bizarre to think there’s an actual baby in there.’ She was staring at my still reasonably flat stomach.

‘I’m going to get so fat,’ I said, laughingly. Weirdly, this seemed a matter of mirth.

‘Yeah, you are,’ she asserted, sniggering too.

‘And no one is ever going to want to marry me.’ Suddenly, I wasn’t laughing anymore. I was, to my horror and shame, crying. The tears came in huge, uncontrollable waves. I gulped and gasped for air in pretty much the same way I had when I’d been laughing, so it took Abigail a moment to notice.

‘Oh no, don’t cry,’ she said, pulling me into a tight hug. She smoothed my hair and kissed the top of my head, the way a mother might comfort a child that had fallen over. Abigail was beautiful and sensuous – everyone wanted to touch her, all the time – but she generally chose when any contact would happen.

‘Who will want to marry me when I have a kid trailing around after me?’ I hadn’t actually given much thought to marriage up to that point in my life. I wasn’t one of those who’d forever dreamed about a long white dress and church bells, but I’d sort of assumed it would happen at some stage in the future. It frightened me that the undesignated point seemed considerably more distant and blurry, now that I was pregnant.

‘You’ll still get the fairy tale,’ Abi said with her usual cool confidence. ‘I mean Snow White had seven little fellas hanging off her apron and she still netted a prince.’

This caused another round of near-hysterical laughter. I laughed so hard that snot came out of my nose. It was embarrassing at the time. A few months on, I became much more blasé about wayward bodily fluids. She hugged me a little tighter. ‘They will call you a slag, but it will be OK,’ she assured me.

‘Will it?’

‘Yeah, it really will,’ she said cheerfully. I felt a wave of something like love for Abi at that moment. I loved her and I believed her.

That feeling has never completely gone away.