Читать книгу The Mystery of You - Adin Steinsaltz - Страница 6

Introduction

ОглавлениеHow young are you? Are you satisfied with your life? Do you have fresh challenges ahead and new things to look forward to? Are you suffering from unfulfilled expectations? Have you come to terms with who you are and what life is about?

I am already closer to sixty years young rather than fifty years old. Sounds like a contradiction? I don’t think so.

I have been writing these thoughts for well over ten years now; a bit here and some more there. It has been challenging as well as fun. My thoughts rush through my mind, but move from pen to paper ever so slowly. I print each word in bold characters, letter by letter. No clear plan initially, just a flow of ideas and experiences. My left hand struggles to keep up and smudges over the inked lines written on the sheets of paper as it steers my pen.

Although I have a very busy life with no spare time, I always have the impulse to write: a bit in airplanes, some more during vacations, occasionally taking an hour off on the run or late at night. Even a few minutes in the car, in between the normal rush, but always moving forward, finding just little snippets of time to write, then to write a bit more and to write in between everything else.

Thomas Nisell is more like a brother than a friend. Affectionately called Schwedi (Swede, in Hebrew), he made aliyah (immigration; literally – “ascent”) to Israel from his native Sweden. We have much more than salmon, herrings and fine whisky in common. Thomas is blessed to be the personal assistant of Rabbi Adin Even Yisrael Steinsaltz. I am indeed fortunate to have Thomas as a brother and the Rabbi as a soul mate.

The Rabbi read these chapters in draft form. We had an amazing time together at the Vatican in Rome over six years ago at an interfaith dialogue; we stayed there for nearly a week and made time to work on this book. I will never forget one particular session one afternoon. We were sitting by an old wooden table in the old kitchen of the old gatehouse in the beautiful garden of the old Piccolomini Estate, next to St Peter’s. We became silent and just looked at each other. We felt exhausted.

I noticed the time. It was starting to get darker outside. We had been discussing and thinking and talking intensely for over three and a half hours in that session, yet it seemed like no time at all. We had battled about the nature of the yetzer ha-ra (evil inclination) as against the yetzer ha-tov (the good inclination). It was a formidable battle. I felt weightless. I was just floating around the room feeling totally exhausted. It was difficult to keep my eyes open. I felt like drifting off to sleep.

It was time for Mincha (the afternoon prayer). The Rabbi just looked at me with those incredible eyes of his – eyes that can see what others do not see, eyes filled with caring, love and compassion, eyes which were tearing, eyes revealing a depth of human understanding beyond our normal experience.

I met Yehudit Shabta in Jerusalem only about four years ago. She was recommended to me by my friend Thomas Nisell. Yehudit had spent many years working in the Steinsaltz institutions. She is a translator and editor with much practical experience, which includes working on many of the Rabbi’s books. Prior to my visit, we sent her a draft copy of my writings for preliminary evaluation.

It was motzei Shabbat (Saturday night, after the Sabbath is over). We had arranged to meet in the lobby of my hotel – a public place, yet somewhere where we could talk. Somehow, we seemed to recognise each other and sat down at a table. We ordered weak black teas and started talking. We seemed to feel comfortable. I showed her photos of my family. When we got to the subject of this book, Yehudit was very polite. Without wishing to cause any offence, she softly tried to explain that she didn’t think she could do the job. We agreed to meet at the Rabbi’s office the next morning.

I arrived first and had a coffee with Schwedi. “Nu?” he asked me. “How did it go?” I explained our discussions and said that I didn’t think Yehudit would be able to edit this book.

“Why?”

Because her world was too far away from my world and she really was not my primary audience, I heard myself respond. I am not a writer and my work is not presented in any conventional, logical manner.

Then Yehudit arrived. Same questions. She looked at me.

“Please, Yehudit,” I said, “please, just tell it the way you see it and the way you feel.” The Rabbi called us into his study and we sat down. He was puffing at his pipe in his characteristically Steinsaltz fashion. He was surrounded by piles of books and manuscripts. We were all multilingual and very comfortable together, but decided to speak in Hebrew because I thought that this would be the most natural for Yehudit on this occasion.

Same questions, this time from the Rabbi. Yehudit looked at me. I encouraged her just to tell him the way it was.

Yehudit looked at the Rabbi, then at me and back at the Rabbi.

“Ze lo mesudar.” (Literally: it is not orderly; meaning: it’s a mess and I really can’t do this.)

The Rabbi looked at her with those eyes of his. It was as if he could read inside her mind. He said to her, “I think this will be good for you to do.”

“I don’t understand,” she meekly responded.

“I think that this will be a very good thing for you to do,” he repeated.

“But, I don’t understand,”, she offered. “Ze lo mesudar.”

The Rabbi smiled and asked her in his soft, very human voice. “Have you ever seen a Japanese garden?”

“Actually, yes, I have,” Yehudit replied with some surprise in her voice.

“What did you see?” he asked.

“I don’t understand,”, she repeated.

Then we all heard what only Rabbi Steinsaltz could say. “You see, there are all kinds of gardens. For example, consider a French or an English garden: what do you see? Everything is perfectly put in place. Every leaf is manicured. It is very beautiful to some people and is mesudar (in order).

“Now you walk past a Japanese garden. It is not for everyone. You might not stop to look in. But if you do go in, what do you see? A rock over there. A tree over here. Maybe even some water. Maybe you find a seat. If you look closer you might imagine a picture – some kind of colours and patterns and textures. It is a bit like some forms of modern art where you see a bright yellow ear over here and a red shape of a leg, upside down, over there and a blue hand sticking out of a distorted green body. That is what you have here. Sometimes there is a deeper beauty, even though on the surface it appears lo mesudar,” he said. “It is not for every person, but some people like it. I think this will be good for you.” Yehudit sat silently, deep in thought.

Thus began our working relationship. It has only grown and become much deeper and open, full of mutual respect. It has also been lots of fun. You can just imagine the “in jokes” about me.

Why is the book not mesudar? Because real life is not mesudar and most people think and live in a non-mesudar way.

Few people have had the opportunity and privilege to be able to be truly inspired intellectually. Many people have become “turned off ” by bad experiences, mainly perpetrated by bad examples. Consider the schoolroom: how many people feel excited to re-enter a classroom? Most of us lack motivation and inspiration to even give it a try!

If my book does anything positive to help people to improve their lives by exciting their imaginations to experience new, positive and creative experiences, then I am a very happy and fulfilled person.

I hope to offer some kind of a glimmer of light which shines or sparkles out through the small window of such an apparently empty classroom – out onto the street. I hope to attract some curiosity for a passer-by, who probably would not have given this simple, plain classroom even a first look, let alone a second.

If I succeed in this, if I make the passer-by pause and think and notice the window, then, maybe this person might feel like coming a bit closer and taking a little time to peep inside the window. And if this casual peep of initial curiosity yields an attractive picture, then perhaps these people might wish to step inside to gain a closer look. This is where they will personally meet my very dear friend, Rabbi Steinsaltz. Then a new panorama of life will open up for them, a new dimension, a new relationship.

I explore the idea of happiness in life and try to build it into a framework of freedom and liberation. Liberation from what? From the mundane, the physical and the material that are devoid of the spiritual.

I play with the whole concept of rules, regulations, restrictions and limitations (“fences”) in societies and in communities. We do need fences; fences define who we are and, even more importantly, who we will become.

Who makes the fences? Who defines the rights and the wrongs? What have morality and ethics got to do with everyday living? Why? Who is inside the fence and who is on the outside? Who is sitting on the fence?

The true fence lies inside each person. We can think, imagine, dream and experience life within the fence, which is healthy – or risk exposing ourselves to dangers by allowing, or even enticing and then encouraging our minds to venture outside the boundaries imposed by the fence.

This is about human behaviour.

In this book I float through water, life and numbers. An apparently strange combination? I venture out on a voyage of discovery to explore the differences and similarities between science and belief in G-d. Science? Religion? Are they mutually exclusive? Or can they coexist in harmony and equilibrium?

I question what life is and the process of living and ageing: birth and death and what lies in-between. Beginnings and endings. The forces of good and of evil. Why? What is this all about? This is the unique journey which every person experiences through living life.

I have become so enriched, personally, by applying my mind to such issues and by putting pen to paper. I have discovered the joy and the privilege of growing and of understanding, the pleasure of fulfilment, the peace and serenity of being.

Living through ageing is the voyage of our body and mind, as they encounter the very essence of their being. It is the confrontation of one’s yetzer ha-ra and the coming to terms with one’s “fence”.

I challenge how one’s personal belief can engage with communal bureaucracy and then I confront the issue of continuity: continuity of what?

At this point it is appropriate for me to express my heartfelt gratitude to one of this world’s very special people, my secretary and personal assistant, Maree Thompson. Maree has devoted over thirty years of her life to my family. Not only does she work tirelessly and aim always for perfection – a big call for a mortal human being – but, even more importantly, she is a Mensch (Yiddish: a very positive and decent sort of human being), with a capital “M”. Maree organises my life and our group of companies. She is the very efficient behindthe-scenes quiet achiever. On top of everything else in our hectic week, Maree gets dumped with all of my papers and bits and pieces. These include my lo mesudar writings, with never a comment or complaint.

Maree typed it onto the computer, fixed up my spelling mistakes and added in her own little notations for me to look at after she had finished with a batch of work. She is always encouraging and enthusiastic; a very positive person. So, a big, special thank you to my Maree.

There are three other very special people in this world who have also greatly impacted upon me and my life. These are our “proof readers”, in alphabetical order – Timmy Rubin, Orlee Schneeweiss and Vivienne Wenig. Thank you, thank you, thank you. You have injected much more than your language skills. You have given of the heart and touched the soul. Your advice, encouragement and positive feedback is inspirational and this has nurtured me beyond words. I express my heartfelt appreciation for who you are.

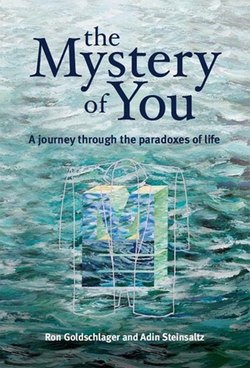

Victor Majzner – we have known each other even before we met. Your artistic expression is inspirational. Your work sings and dances – it is passionate and alive – it talks! The colours, shapes and harmony of balance resonate into the soul; Kabbalah, Midrash and Torah – Israel, Australia, humanity, nature and the Divine – all connected together. Thank you, Victor.

Thank you to Leor Broh for assistance in translations and interpretations; and Rabbi Eli Gutnick for his creative hand-written illustration [fig. 1].

I also wish to thank my family and to acknowledge their advice and support over all of this time. Dina is the matriarch of our family. She grew up in Israel under very difficult conditions, arriving there as a one-year old, Italianspeaking immigrant. She was raised without a father and her late mother had to work hard to support the family. At fifteen she moved to Sydney, Australia, where she had to learn English while completing her high school education.

Today we are blessed with four children, all of them married to wonderful partners in life who are also like our own children. They are all university-educated and have good careers. Most importantly, all are fine, decent, honest and caring people. We are blessed with ten beautiful grandchildren whom we see a lot of and enjoy immensely. We are all very close and share an intimate, loving and caring relationship.

Over the years Dina, Tony and Sharon, Sharonne and Michael, Tammy and Joel, and Dalia and Adam have encouraged me and have also been variously critical of my work. All in all, my gratitude and unqualified love goes out to each and every one of you. Without you, I could not have achieved this work.

I am a lucky person to feel loved by so many.

There are many kinds of love and one can love many people at the same time. There are also many colours and dimensions of love. Each love contains overlapping feelings, devotions, passions and loyalties; but despite the overwhelmingly similar qualities, there are also differences.

It is good to love and to feel loved. In fact, life is terribly empty when it is devoid of love. People search for perceived love in so many ways and, sadly, so often the search proves to be futile. Perceived love is not true love. Love is inside a person. It can be opened up and nurtured or it can be suppressed and denied.

It is healthy to tune into the warmth and the love which is all around. This is what life has to offer as its most sparkling treasure.

There are some wonderful people who have devoted quality time to reading the early drafts of the chapters contained in this book. You know who you are and your encouragement, support and assistance to me have been invaluable. Thank you.

These people include a wide range of different human beings: young and less young, religiously observant and non-observant, intellectuals and everyday people, passionate and passive people from many walks of life and of different nationalities. Some became deeply involved. Many encouraged me with their patient feedback. Some were even inspired by what they read.

From my own, personal point of view, I have gained and grown immeasurably from all of your truly amazing feedback to me. You gave my writings literary credibility, spiritual personality and human value. Moreover, you helped bring all of the various parts together for me and breathed life into it so that it became a complete book, a work of integrity.

We were finally ready for publishing, but Thomas (Schwedi) cautioned me as he shared his experiences. This initiated a new search over another year – may I say, a most worthwhile search, after many meetings, thanks to Ze’ev of Sunflower Bookshop in Melbourne. We could not have worked with finer publishers than Hybrid Publishers. Thank you Louis de Vries for your warm, personal, professional commitment and thank you, Anna Rosner Blay, artist, creative writer and talented editor-in-chief.

Thank you, my friends. This book is for you all.

I pray that Rabbi Adin Even Yisrael Steinsaltz should be healthy in long life, to continue to share all of his wisdom, together with his humility and humanity and thus to help improve the world.

Thank you for sharing my thoughts and my journey. Nesi’ah Tovah – bon voyage – with yours.

Enjoy the journey more than the destination. The joys of life are in all of the little things along the way.

Ron Goldschlager Melbourne, Australia 2010