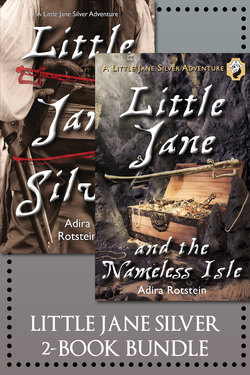

Читать книгу The Little Jane Silver 2-Book Bundle - Adira Rotstein - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 8

ОглавлениеThe Knot That Was Not

“PLEBLLLLEFFFFFF!” Bonnie Mary spluttered, pulling her head out of the basin of cold water. Instantly, she knew it would be a Three Cups of Coffee Morning. What had she been thinking by making an early appointment for the morning after their party?

Long John helped his wife into her dress, lacing her up in seconds with his nimble sailor’s fingers. Bonnie Mary pulled a pair of clean white gloves over her calloused hands and tugged a few curls out of her mobcap, carefully positioning them over her bad eye. Last, she powdered her face to soften the effect of her sea-weathered features.

Long John straightened his white horse-hair wig and tied his finest silk cravat before the mirror. Bonnie Mary fluffed up the new orange feather in his hat, while he gave the gold-topped cane he carried for special occasions a final polish. At last they were ready to go.

Bonnie Mary glanced over at Little Jane, still huddled in her little hammock bed. She had hoped to bring her along, seeing as how it would be a lesson in the business side of smuggling and pirating, but the previous night’s revelry seemed to have exhausted the child.

“Let her rest,” said Long John, extending his hand to his wife. “It won’t do to keep the coffee trader waiting.”

Bonnie Mary took the proffered arm and the two sauntered down the gangplank to the pier, looking for all the world like any well-dressed, middle-aged couple out for a morning stroll.

A few hours later, Little Jane woke. She stretched out luxuriantly against the pillow of her bed, watching the sun stream in through the cabin window, sending dust specks glowing in the air. A magical morning. She stumbled into her clothes, taking note of her parents’ empty bed.

Where were they?

Patrolling the deck of the Pieces once more, even Ned Ronk felt in good spirits as schemes of sabotage wove their twisty way through his devious brain. He watched a few stray sailors mop the deck.

Someday he’d have a ship of his own, he mused. Perhaps this ship, even. All it would take was a little finesse. The important thing, Ned realized suddenly, was not, as Doc Lewiston had said, for the act of sabotage to be completely untraceable. No, what really mattered was only that it be completely untraceable to him.

All he’d have to do was find the appropriate dupe to pin the thing on, someone no one would ever suspect of having any connection to him …

As if on cue, Ned Ronk noticed Little Jane’s small, braided head poke up from the entrance to the midships. He clenched his fists with the desire the squeeze someone’s throat, but then a flash of inspiration struck him. With a grin of supreme friendliness and goodwill, he waved at Little Jane.

Little Jane ducked back down to the comforting darkness of the hold, barely able to breathe. Her heart banged in her chest as memories from the night before all came flooding back.

Ned! That sardonic wave of the hand … He knew! He knew she had followed him to Sharky’s! Of course he knew! He had to know! And that meant she was done for!

Whatever Ned had been planning with the man he’d met in the tavern, she knew it wouldn’t bode well for her. Something had to be done. It was time to tell someone. But then she remembered the empty bed in the captains’ cabin and knew by the angle of the sunlight shining down on her that it was afternoon already. Her parents would be at the coffee merchant’s by now.

She realized that Ned Ronk wouldn’t dare try anything in Habana, not with all the soldiers and townspeople about. Her parents could find a new boatswain to replace him — they were probably a dime a dozen around here — this was Habana, after all! She had to tell them and tell them NOW — now, before they went out to sea with Ned. Out at sea where there would be nowhere to run …

Suddenly, as if he’d read her very thoughts, there was Ned, standing right above her! From up on the deck, he peered down at Little Jane in the hold. She trembled under his squinty gaze, fixed like a butterfly on a collector’s table by the pin of her fear.

“Little Jane …” his voice rumbled.

She chewed on one of her braids, sniffing the vaguely salty scent of her hair for comfort, as the clasp-knife gleamed in her imagination. But the clasp-knife never made an appearance. Instead, Ned Ronk smiled, actually smiled at her. He even reached down and patted her on the head!

“Why don’t you get a mop and give Rufus a hand cleaning,” was all he said, his tone unusually mild. “There’s shrimp stew all over the bowsprit.”

“Aye-aye, sir!” cried Little Jane in surprise and she ran off looking for a bucket.

Little Jane never did get a good moment alone with her parents to tell them about Ned Ronk’s secret with the stranger in Habana. For the next two days, the boatswain watched her like a hawk and stuck to her like tar to a feather. Worse luck was the hard work of getting the ship ready for departure that kept her parents up on deck at all hours instructing the crew on how to load and unload the goods they were trading. Little Jane tried to stay awake, but much to her chagrin, she always managed to fall asleep long before her parents came down to go to bed at night.

The time came for them to sail far too quickly. Little Jane gazed miserably at the buildings of Habana harbour as they receded from view along the blue horizon. The snapping sails carried the Pieces of Eight out to sea, seemingly in no time at all.

However, Little Jane had no intention of taking these difficult circumstances lying down. “If I can’t tell anyone,” she reasoned to herself, “least ways I can keep an eye on things and make sure Ned don’t get up to more mischief.” In that spirit, Little Jane spent a few monotonous days spying on the boatswain. Strangely enough, Ned did nothing more suspicious than urinate off the quarter deck when he was supposed to be on watch. As the days went by, her spying activities dwindled to the occasional sneaky hour or two caught in between her own ship’s duties.

Little Jane wondered if perhaps she had confused the meaning of what she’d seen that night in Habana. Maybe the man she’d seen climb down the rope hadn’t really been Ned at all. Even if it was Ned, it didn’t mean he’d necessarily been up to no good. And even if he had been up to no good, he was only one man. As long as she stayed near her parents, she was protected, for he was certainly no match for the two greatest pirate captains to ever sail the seven seas. There was nothing to worry about, nothing at all.

A good captain always retains a level head in the face of danger and makes decisions based on proper evidence, not fear. Wasn’t that what she’d been told to write down in her book by her mother?

She could manage to convince herself of it during the day, but in bed at night, with “How to Be a Good Pirate” unreadable in the dark, she found a level head was not the easiest of things to maintain.

As always, the first day of the month was Cannon Defouling Day on the Pieces of Eight. It turned out that the auspicious date had not come soon enough, for seagulls had made homes for themselves in several of the aft cannons, thoroughly clogging them with their nests and droppings. The four-pounders, although much better off, were choked with spider webs, not to mention rust, dust, salt, and seaweed.

Despite being too little to help carry the smaller cannon barrels up to the main deck for cleaning, Little Jane’s job was still crucial to the success of the enterprise. It was she who was responsible for tying the knots that held the cannons in place and with her small, speedy fingers she was exceptionally good at it.

She had just tied down the second aft cannon, called “Mr. J. Thunders” (all cannons on the Pieces had names), when Ned Ronk sent her down to storage to get more grease.

Little Jane returned to find the rest of the crew hard at work on the other cannons — “General Wolfe” and “Typhoon.” She noticed Mr. J. Thunders moving in an odd sort of way as she approached.

The Pieces of Eight listed to port as the ship hit a big wave. All at once, J. Thunders rolled free, burst through the railings, and plunged towards the sea in a shower of splintering wood.

Little Jane tried to snatch the ropes as they slithered past her ankles. She managed to grab one mooring rope and held on with all her might. Her arms and shoulders shook with the effort, but she was too weak to stay the cannon’s progress one iota. The rope shot through her hands like a live thing, stripping the skin off her palms as it went. Then the cannon paused in its descent, swaying precariously just below the railing, held fast by one unbroken strand of rope.

She grabbed the taunt rope.

For one miraculous second it held. She pulled with every fibre in her body, ignoring the coarse hempen hairs of the rope as they poked into the raw flesh of her palms.

J. Thunders swayed below her like a pendulum, striking the hull of the ship with a sickening sound of shattering timber.

She might as well have tried to bend iron.

The single strand broke and the rope exploded out, lashing out at Little Jane like a whip across her forehead. She fell senseless to the ground and J. Thunders tumbled into the ocean, never to be seen again.

It had all taken little more than a few seconds.

A flurry of orders broke out and Long John rushed over to where Little Jane lay, just coming to, on her back on the deck. She opened her eyes to find herself enfolded in his brawny arms.

The pirate captain’s concern poured out in a babbling stream of words. “Jane — Jane, oh Jane, thank God — what — what was ye doing? Yer head! Good lord! What was you thinking? You’re hurt!”

But Little Jane just sat blinking at the broken railing and the rust-stained deck planks where the massive cannon had been, as if it were all a mirage. It seemed impossible that such a huge thing as J. Thunders had so suddenly up and disappeared.

“Not hurt,” she replied vaguely, but her forehead felt hot and wet in the place the rope had struck her and there was blood around the cuffs of her shirtsleeves.

“You are hurt!” protested Long John.

“I’m not hu—” she started to argue, but then the palms of her hands began to smart so terribly that tears filled her eyes.

“What happened?” asked her Papa.

“I … I …” What had happened anyway? She had tied up the cannon’s ropes, and then gone down below to get the fat to grease the wheels. She had come up again and J. Thunders was … going over the side? It made no sense. She groped in her mind for some explanation.

“It’s her fault!” someone shouted. “The cannon ropes weren’t tied proper!”

Without looking, even through her throbbing headache and burning hands, she knew that voice.

“Eh?” Long John looked up, puzzled.

“Look!” Ned Ronk cried and he pointed to the empty deadlights fixed to the deck that the rope should have been tied to.

Gasps and curses broke forth from the crowd of sailors.

Long John looked from Little Jane to the deadlights and back again. “Jane …”

“It weren’t me,” she swore vehemently through her tears. “It weren’t me! I swear it!”

“But it was your job — tyin’ down the cannons!” called out Changez.

“How we gonna defend ourselves now?” grumbled Mac the gunsmith.

“Shaddup, woodworms!” bellowed Long John. “We still got a slew o’ cannons! Leave ’er out of it!”

But somehow this did little to staunch the crew’s anger toward Little Jane. She curled up further into her father’s belly, making herself as tiny as possible, trying hard to pretend she did not hear the voices of people she’d known and lived with like family all her life turning so swiftly against her.

“What you get fer letting a child do a man’s job,” muttered a scornful Cabrillo.

“Just ’cause she’s kin to the captains—”

“No good ever come of having a girl-child onboard, I always says, but no one ever listened—”

“An ol’ fashion floggin’ oughta teach ’er!”

“SHUT YER TRAPS!” bellowed Captain Bright, face scarlet with rage as she stomped onto the poop deck, brought up from her charting work below to investigate the source of the sudden commotion.

“He’s right, Cap’n,” said Ned Ronk evenly to Bonnie Mary. “She oughta be flogged. If it were any one of us, we’d have to learn our lesson. This ship’s supposed to be a floating republic! With all respect, Cap’n Bright, you and Cap’n Silver ain’t kings and queens here. We all signed the charter! Equal parts o’ everything!”

“I tied it right! I did!” Little Jane protested, but even to her the words sounded pathetically small against the tidal wave of angry voices.

“Flog ’er! Flog ’er!” The chant rippled through the crew assembled on the deck.

Little Jane listened, feeling strangely detached. The thing was, she understood. Although she had no desire to be flogged, she could see their point. You had to be able to trust everyone on your crew to do their job or you’d end up at the bottom of the ocean. A weak link in the chain could easily mean death, and there was enough to deal with at sea without your shipmates proving unreliable.

In the face of it all, her resolve began to weaken. She wondered whether she really had tied the knot off properly. It was possible it hadn’t been tight enough. She should have double checked. She should have asked. She should have—

The terrible thunder of her father’s voice cut through her thoughts.

“She’s under my command,” growled Captain Silver. “My responsibility. You all want te flog someone? Flog me!”

With a dramatic gesture, Long John tore his shirt off and flung it to the deck. His broad torso shone with sweat. The tattoo of a skull in flames grinned back at the protesters, a prediction of the dire fate that lay in store for any man fool enough to cross the captain.

Although Little Jane had not initially seen her father remove the elegant mother-of-pearl handled duelling pistol from his belt, she saw it in his hand now. He held it loosely, as one would hold some meaningless accessory, but his show of carelessness fooled no one.

The entire ship grew silent. Waiting.

Unruffled, Ned glared back from the other side of the deck.

Little Jane heard the slapping of the waves against the hull clearly in the silence.

Then Long John was crossing the length of the deck toward the boatswain. He did not rush at Ned, but moved deliberately, the way one might approach a wild animal; he held the elegant mother-of-pearl-handled duelling pistol casually in his hand; the sword on his hip jingling ever so slightly in its scabbard to the rhythm of his uneven gait.

Step-scrape. Step-scraape. Step-scraaaape. Step-scraaaaape. He stopped with half the deck still between them.

He would go no farther, Little Jane knew, for this was the perfect distance for a pistol duel; Close enough to make your every shot go home, but still too far to let them lay a hand on you. Just as he’d told her to write down in her book.

Stark, unreasoning terror gripped her heart, but her father’s eyes — blue as the heart of a flame — now looked as if nothing could be more certain than his victory.

From her post at the bow, Bonnie Mary squinted down at the boatswain, a vicious sneer roiling across her scarred face. With a sickening thok-click she cocked her own flintlock rifle. A big gun for a little woman, as Mendoza had said. She would finish Ned off if her husband failed.

“You’d like to have a go at me, eh?” Long John asked Ned Ronk lightly, as one would inquire after the weather. “Fifty paces at the next island we sees? Or shall we take it now? While the sun’s still out then?”

And like the snuffing of a candle, Ned’s rebellious momentum was gone. “No, sir,” he replied with submissively downcast eyes.

Bonnie Mary nodded, taking over where Long John left off, turning curtly to the rest of the men. “Get back ta work, ye seadogs! We got thirty-two more cannon to clean and that sun ain’t getting any higher! Hop along Lockeed, that cannon ain’t gonna grease itself!” she bellowed, giving the gunner’s mate a boot in the rear end for good measure.

To Little Jane’s amazement, her mother roared out these orders as if nothing untoward had just transpired. Weaving in and out between the men, barking further directions, she seemed as calm and unflappable as ever. But upon looking down, Little Jane noticed, protruding from the sleeve of her mother’s jacket, the nasty gleam of a knife and remembered Mendoza’s words to her about her mother’s speed with a blade.

Little Jane looked away with a shiver, only to notice an awful splash of red on the deck. Her stomach lurched as she took in the sight of her hands.

“Rufus!” shouted someone in the distance, as Little Jane hit the deck in a semi-faint. “Hey, Rufus, get the mop!”

Hours later, Little Jane sat alone in the cabin she shared with her parents.

Her disposition had ventured into solidly lousy terrain. How she would have preferred a physical flogging to the verbal interrogation she’d had to endure that afternoon. How many times could she be asked exactly what happened with the cannon? And was she sure she’d tied the knot off right? How could one be absolutely sure? She’d done such knots so many times before that she no longer thought consciously when she made them.

She sighed and let the gloom take her for a while.

She was nearly asleep when she heard a familiar, uneven step in the companionway outside the room.

“Papa!” she called out to him, worried he might think she was sleeping. Long John ducked his head through the door.

“What’re you still doing up?” He pulled up a stool beside Little Jane’s box hammock bed and sat down.

She tensed, anticipating the harsh words she knew she so richly deserved, but he merely gazed at her intently, as if to reassure himself she really was all right.

Little Jane never looked at her father much straight on. Neither one of her parents ever tended to sit still long enough for that. But now, for the first time, she noticed that his eyes, which she always assumed were just simply blue, were actually as changeable as the sea in colour, first green, then blue, then a pale gold like the eyes of a cat.

He took one of her hands and carefully felt the bandages, making sure they were applied properly.

She gasped as he prodded a particularly tender part on the heel of her palm.

“Hurts the blazes, don’t it,” Long John said philosophically.

“Aye.”

“Well, ye ain’t the first sailor to get rope burn and ye won’t be the last. Ya know, when I were a lad, got it into me head to rig a climbin’ rope off the ceiling of the Spyglass and cut me hands up something awful!”

“Thunders is lost for good, ain’t he?” asked Little Jane before Long John could break into another story.

“Aye. But what of it? It be just a cannon.”

“Not just a cannon. A crack twenty-four-pounder.”

“There be plenty more twenty-four-pounders in this world where Thunders come from. Ain’t but one o’ you, Little Janey,” he said, his voice cracking on her name. “Me and yer mum, we broke the mould for you.”

Long John looked away and suddenly Little Jane felt odd inside, as she realized her father was trying not to cry. There was quiet in the cabin as Long John paused to master himself. A room with him in it was never silent, and it was his silence more than anything else that disturbed Little Jane the most.

“You shoulda just let ’em flog me!” she blurted out.

He shifted back to her and spoke again. “Naw, couldn’t let that happen, love. According to our charter it’s the bo’sun what does the flogging, excepting of course when it’s him that’s needing the punishing. You know that.”

It frustrated her how everyone was always expecting her to “know” things no one had ever precisely told her. In practice, there was so little flogging done on the Pieces of Eight, she had remained unaware of the rules regarding it.

“I wouldn’t want Ned to — well, let’s just say he got a heavy hand with these things. He don’t mess about,” Long John said with a shrug. “The threat alone’s enough to keep most of the crew in check.”

Little Jane shivered at the thought of Ned Ronk with the cat o’nine tails in his meaty fist. She desperately wanted to tell her Papa about all she’d learned about him. The words nearly leapt out of her mouth then and there, but the image of that clasp-knife, the blade glinting cruelly in the sun, crammed them all back down again. Forgetting her injury, in her frustration she smacked the side of the box hammock with her hand.

“OW!” As the pain subsided, it dawned on her that Ned wasn’t the only one she had to worry about now.

“How’ll I ever face ’em all up on deck again?” she moaned. “They hate me! They all do!”

Long John chuckled. “Honestly! I don’t know where you get these crazy notions. Some o’ these folks knowed ye when ye weren’t more than a twinkle in yer bonnie mother’s eye. Now I ain’t discounting your worries, but wounds heal and men forget quick, much faster than you do, you’ll see.” He kissed the tops of her dark braids.

She nuzzled her head up against his broad chest like a kitten, yet somehow failed to get her customary feeling of comfort from this action. Instead, all she felt was immense frustration. How could someone understand both so much and so little at the same time?

“Now then, what’s this?” Long John picked Ishiro’s sketchbook out from between her bedcovers. Little Jane forgot she had brought it into bed with her to look at the night before.

“Oh, just something Ishiro gave me.”

Long John flipped through a couple of pages filled with depictions of sailing life — jack tars hauling line, mending nets, scrambling up the rigging … but then he stopped, his gaze arrested by a particular image. Little Jane bent toward her father to see what had so captured his attention.

In the drawing were three lads. Two were tousle-haired boys (cook’s apprentices, most likely, she thought), sitting skinning potatoes in a galley kitchen, an enormous checkered cloth spread across their laps and over their crossed legs to catch the peels as they fell. Their mouths were open as if talking, their faces animated. They looked very alike and Little Jane would have thought them twins if the one had not been so fair and the other so dark. There was a third, a handsome older boy who sat beside the pair, tamping a plug of tobacco into his pipe, the corners of his mouth turned up in a smile, exposing two missing front teeth.

It was odd to think that the people in the drawing were probably adults now, Little Jane mused. Or perhaps they had never existed to begin with and were simply creations of Ishiro’s imagination. Yet somehow, she thought not. The missing front teeth of the older boy with the pipe, the crinkles around the smiling eyes of the fair-haired boy as he peeled potatoes, the sidelong glance of the dark eyed boy with the long eyelashes, even the distinct pattern on the potato-peel-filled cloth lying across their laps, seemed details too real to be mere fiction.

“Who were they?” she asked her father.

“Friends o’ mine,” mumbled Long John, his words uncharacteristically wistful and indistinct. “We was shipmates.”

“Really?”

“It was a long time ago. Before the loss of the Fleece and the Newton even.”

Little Jane nodded solemnly. She couldn’t remember when she had first learned of the two lost ships, but the stories had always been there, embroidering the edges of her existence. One couldn’t serve long aboard the Pieces without hearing at least a little about the Newton and the Golden Fleece, the Pieces’ sister ships from long ago.

Yet for all that, Little Jane had as yet to form a coherent picture of how the great disaster had occurred. Conversations had a tendency of cutting themselves short when talk began of the Newton and the Fleece. Too painful to sustain for very long. She supposed now was as good a time to ask as any. Somehow, looking at her father just then, she felt that for once in his life he might actually give her a straight answer.

“What happened to the Fleece and the Newton, Papa?”

“You know, darling.”

“I forget. Papa, please.”

Truth be told, Long John wasn’t sure he had a coherent picture himself of what exactly had happened that horrible day and he had actually been there. He’d turned it over so many times in his head, trying to figure out just where he’d gone wrong, but no matter how many different scenarios he danced like puppets across his mental stage, he still couldn’t figure it. Each choice he came up with still demanded a sacrifice of one kind or another. He had chosen with his heart. His sweet Bonnie Mary lived as a result, but others had not been as fortunate.

“Tell me,” coaxed Little Jane.

And with a sigh, he did.