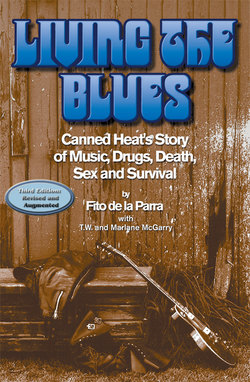

Читать книгу Living the Blues - Adolfo de la - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 - THE EARLY YEARS

Оглавление"Don't forget. Your body is your limitation. The answer = Yoga.

"Love, Noreen

If Noreen Reilly and Alan hadn't turned me on to yoga, I'm sure I wouldn't be alive today. You can't spend your life abusing your body and not expect it to catch up with you.

Noreen was also a wizard at astrology. I gave her all the necessary details: born Adolfo Hector de la Parra Prantl, Mexico City, February 8, 1946, 1:20 in the morning.

A few days later, she handed me astrological charts that turned out to be surprisingly accurate. According to the stars,

I'm a lover of peace and harmony.

•In my quiet way I get what I want and make the other fellow like it.

•In youth stubbornness, but with maturity a fixedness of purpose.

•My strong point is organization.

•I have all the qualities necessary to be a good leader--except the desire to be one.

•My father's line shows material achievements.

•I'm attracted to 'wimmen' (she used to make fun of my accent) and I'm quite unconventional in regard to sexual matters." Not bad for someone who had only known me days and the majority of that time was spent tripping on acid.

I was named after my maternal grandfather Adolfo Prantl, a stern, aristocratic Austrian and a very staunch, ultra-conservative Catholic. I must have inherited my sense of order from him and it's one of the reasons I like traveling in Germany. Offenses aren't just prohibited; there are degrees of how forbidden something is: breaking the law may be verboten (forbidden) or in some cases strikt verboten (strictly forbidden) and if it's really terrible, it's strengstens verboten (absolutely forbidden).

Don Porfirio Diaz, the Mexican dictator who coined the phrase: "Poor Mexico, so far away from God and so close to the United States," invited my grandfather to move to Mexico to help organize customs and the import/export laws.

Don Adolfo's mother and his brother Jacob came with him and he waited to marry until his mother died. A handsome aristocrat who walked with a gold-headed antique black cane, he was never seen without a tie on his high-neck shirt, an embodiment of 19th century values. My chief memory of him is sitting in his smoking jacket, reading a book. He was a great architect and some of his buildings have been declared historical. After 100 years and all the earthquakes in Mexico City, the Prantl buildings are still standing.

One sign of affluence Adolfo refused to acquire was an automobile. The house had a four-car garage, but he didn't believe in them. I guess the environmentalists would have loved my grandfather.

When he was in his forties, he wanted a bride who was untouched by the world and by temptation. What better place to look than a convent. Pilar Baguena was 16 or 17, and had fair skin, brown eyes, and long blonde hair. Her parents, originally from Spain, were both dead and the convent was a safe haven for such a young girl alone. She was a gifted painter and recited poetry. I have some of the letters my grandfather wrote to her; they are very beautiful, very romantic. They really did live happily every after. Relationships like that don't exist any more. In the United States, society is very hung up on age, but in Europe a man twenty years older than a woman is no big deal and in Latin America, it's even less of an issue.

One of the fascinating things about Mexico is the profound European influence and connections, which are very strong to this day. My family was very much a part of that.

People who haven't traveled in Latin America tend to think of Mexicans as a mass of poor, uneducated wetbacks.

They don't realize that Mexico City was a thriving, sophisticated city two centuries before the Algonquins sold Manhattan to the Dutch for $24. In 1864, when Austrian-born Maximillian was emperor and French-born Carlota was the empress, they brought over the same architect, who designed the famous boulevards of Paris, to build Chapultepec Castle and lay out the city's avenues, patterning them on those in the French capitol.

My great-grand uncle, by the way, donated the caballito, the statue of Spanish King Carlos IV on a horse that's one of the main landmarks on the Reforma, the main boulevard of Mexico City.

My father's father was born in Spain and my paternal grandmother, Catalina Luccioto, from Palermo, Sicily, was an opera singer with beautiful green eyes and a heavenly smile. She married Gonzalo de la Parra, a blue-eyed intellectual publisher with the looks of a movie star and the soul of an adventurer. By the time my mother and my father married, his parents Gonzalo and Catalina were already divorced.

Even though my grandfather Gonzalo was very much the free-spirited playboy, while Adolfo was very Catholic and conservative, the two got along well. Both were powerful and wealthy but honest. They neither stole nor killed--rare restraint in an oligarchy.

He was exiled from the country two or three times between the late 1920s and the 1950s for his anti-government rhetoric. He even spent three months hiding in a friend's cellar because the police were hunting for him due to his writings. He also became a well-known adviser to two presidents, a good example of the volatile nature of Mexican political life.

My father was a lot like his father. When he met my mother in church and fell in love with her, he was already married "outside the Church" and had a daughter named Laura. Later he had another daughter out of wedlock, Maria Eugenia, who a few years later would have a big influence on me and my musical upbringing.

For the first eight years of my life I was the only child of my parents' church-sanctified union and my grandparents idolized me. I was a spoiled little kid who went to private school and had all the money in the world because both families were still together, with money and power. Our lifestyle was very much in the tradition of European aristocracy. Grandfather Adolfo's mahogany-shelved library was floor to ceiling with books in three different languages and the centerpiece of the mansion's main salon was a concert-size grand piano where grandmother Pilar would entertain us with the works of Chopin and other classical composers. She was also a talented artist and many of her paintings hang my in house in Nipomo. She was close to 100 when she died in 1993, a remarkable woman.

Unlike car-hating grandfather Adolfo, Grandfather Gonzalo would trade in his black Cadillac for a new one each year. In a brief fling with show business, he brought the beautiful Faure sisters from Spain to Mexico to try to turn them into stars. Although the sisters never became great entertainers, they did become famous and the Secretary of the Treasury fell so madly in love with Isabel, he put her face on a five peso bill. Latins really know how to honor women.

Tragically, Gonzalo's death triggered a family feud, which resulted in the beginning of the end of our comfortable life-style and also the end of my family life due to the divorce of my parents. The memory of my father coming to see me at my grandfather's house is still very vivid to me. When I asked him where he had been, all he could do was hold me very, very tightly and cry. And he cried and cried and cried. The strange part was I didn't know why he was crying.

I didn't see my father again for another year. Now, I know it was because of the divorce. He had moved to Tijuana where he was in charge of the local office of the national lottery, a good-paying job. At the time, lotteries were against the law in the United States and Americans would pour into Baja California to buy lottery tickets and otherwise enjoy the openness of a border town.

When I was about six, Pilar bought me my first drum set. I loved playing them but had no idea I was going to become a drummer. I didn't take lessons; I just thumped away. I loved the apparatus. I loved being able to beat on something to make a sound. In fact, I must have been terribly noisy because one day I woke up and the drum set had disappeared. (Most likely Adolfo decided that they were too noisy and hence, verboten.) It didn't really matter. I'd had my fun with it and now I had other interests like cowboys and Indians and my toy soldiers.

After my parents divorce, my mother and I had a very stable home with her parents, Adolfo and Pilar, and my Aunt Rosita. By now, my grandfather was in his 80s but my grandmother was still a young woman. My mother was also very young and not at all happy to be a single mother. But for me, it was great. I was eight years old, growing up with three women who showered me with love and affection.

Because of my parents' breakup, my family decided I should become a live-in student at the same all-boys Catholic school I'd been attending. It was very painful, but I was only in third grade, with no choice. I would cry when my mother took me back to the boarding school after the weekend, but she was also burdened with her tragedies: the loss of Gonzalo, the divorce.

Although I hated the Internado Mexico (it was run by the Marist Brothers, great educators like the Jesuits), I developed a strong sense of order and discipline. No detail was too small for the brothers' rules: how to brush your teeth, how to shower with cold water, how to fold clothes, how to make a bed. The one bright spot on my otherwise bleak horizon was being picked for the choir out of the hundreds of kids that tried out.

In retrospect, I think every kid should have a year in boarding school. I think the survival instincts and discipline I learned there saved me from the excesses of the rock n' roll life years later, from the lack of self-discipline that destroyed so many people I knew in that world. God knows, even with the brothers' training, I developed enough of a taste for some excesses when I grew up.

The Marist Brothers were also skilled at giving young boys a solid academic background. My classical education has stayed with me and enabled me to view the world through more than one prism, something a lot of musicians can't do. And they gave me my passion for history, especially military history--for which I have been frequently cursed by other members of Canned Heat when I've dragged them out of bed during European tours for sightseeing trips to famous battlefields. I once ignored a whole busload of musicians screaming in protest as we made a two-hour detour on the road to Paris to see Verdun, the scene of a famous battle in World War One.

A few years after the divorce, my father decided to move back to Mexico City, marry Maria Eugenia's mother and give the little girl his name. Once I found out he was returning, I started working on my mother to get me out of the boarding school I hated.

I loved my mother and my grandmother (Adolfo had died), but my mother had married again and I wanted to be with my father. He was a very intelligent, cosmopolitan man with a great sense of humor and an aura that I loved. My stepfather Flavio was not a bad man; he treated me well. He was also an excellent guitar player and singer, which would eventually be a musical influence on me, but he didn't have the charisma of my father.

Meanwhile, the death of Adolfo and the division of his estate among my grandmother Pilar, my Aunt Rosita and my mother, caused a marked change in our life style. Overnight I went from an upper class nino bien to a middle class kid. But I didn't care. I was reunited with my father.

Even though he never took lessons, my father was very musical and played piano by ear--everything from ragtime to jazz, anything with a great rhythm. I remember him taking me to one of his favorite movies, "Orchestra Wives," featuring the original Glenn Miller Band. In Mexico, it was called Las Viudas del Jazz, "The Widows of Jazz," because the wives dress in black and go into mourning when the band breaks up. A few years later, we went to see another favorite, "The Benny Goodman Story." Somehow all those messages started going through my subconscious. I'm sure he never thought I would become a professional musician; he wanted me to become a dentist or a doctor.

My father's wife Alicia accepted me immediately and I became very close to my half sister Maria Eugenia, who was five years older. Because she grew up an American teenager in the California border town of San Ysidro, across from Tijuana, she was plugged into the music scene that was exploding in the United States in the '50s. She also inherited my dad's gift for music.

So here I am, fresh out of boarding school, an 11-year-old with all kinds of weird ideas already boiling in my head as my hormones activate, and I meet this half-sister, a gorgeous 16-year-old. The guilt over my sexual feelings for her and her girl friends made them even more thrilling. She also turned me on in another way. She had hundreds of the latest 45 records--Little Richard, Fats Domino, John Lee Hooker, Big Joe Turner and Bill Haley and the Comets. She was an upper middle class teen-ager from a border town, used to hanging out with Americans and really getting into early rock n' roll.

"Check out this music," she would tell me. "It's great stuff. I know that you like Benny Goodman and all that, but listen to Little Richard, listen to Fats Domino." So I really became introduced to rock and roll and to rhythm and blues by my sister Maria Eugenia.

On my 12th birthday, my father gave me an LP, which I still have, called "Here Is Little Richard". My God, I loved it! He bought me a clarinet, a trumpet and an accordion, but I couldn't really get into them. I did, however, start getting into drums. I got an old banged-up military snare drum like the kind they use for marching bands, along with some cookie tins and cans and assembled my own drum kit. I didn't know how the components were supposed to be set up and I had no technique or formal musical training. I would just lose myself, closing my eyes and playing along with those records in a near-orgasmic state fired by my young imagination.

Years later, I discovered that psychologists call this state of mind "flow." It's a universal sensation. Once identified, you know what it is and seek it again. Playing music on stage, riding a motorcycle or making love, I keep looking for it. Some people look for it on drugs but I know you can't find it that way.

At this point, I had no aspirations to become a musician, but that soon changed. At least once a year, the family went to Acapulco. During one vacation, my American-raised sister pleaded with my dad to let her go out alone with an American guy she's just met. But in Mexico in those days, nice young ladies, even semi-Americanized ones, were not allowed to date without a chaperone. It was both her good fortune and mine that my parents figured I was old enough to fill that role.

I will never forget that evening. The nightclub (the first I'd ever been in) was absolutely beautiful--outdoors, right by the ocean. More importantly, for the first time I heard a really great drummer: Richard Lemus. While my sister danced with her boyfriend, I moved to a table right near Lemus and watched every move, thinking "my cookie tins don't sound like that." I spent the evening soaking up everything I could; there was no question that I was bitten by the show-biz bug. I really loved the environment. Everybody was clapping. I thought: this guy's a star--look at all these women.

I couldn't possibly foresee all the treachery the music business would hold for me in the future. As Lemus captivated the crowd, I thought "this is great, this is glamorous, this is wonderful, I want to play and be adored just like this guy. I want to be like him; he looks like he's having such a good time."

It was years before I learned that that's part of the job--you have to look like you're having a good time even if your guts are on fire and your soul is sick and you'd rather be dead than on stage. I learned that part too well, later on.

During this period, I was attending an excellent British-run school called Colegio Williams for Boys. It was not religious, but stern, with lots of English-style discipline. I started making friends with kids who liked rock and roll. That was our link, the only thing we really related to. A lot of them had Elvis Presley records, but I was already farther down the road. I was listening to Little Richard, Fats Domino, and Big Joe Turner.

One of the guys I started playing with was Javier Flores, El Zoa, who had an acoustic guitar. We were among the first garage bands in Mexico City, copying Elvis Presley hits, hanging around just being kids, just making noise. It was all feeling; we had no technique. I hadn't taken any lessons and El Zoa knew only a few basic chords. It wasn't long before we met some other middle class kids in Colonia Narvarte who were also into rock music. Mexico City is divided into neighborhoods called colonias and where you live forms your basic identity. This new group of guys had a piano, a couple of electric guitars and a snare drum. A real Slingerland snare drum with a cymbal. Wow!

They even put a microphone on the piano, creating sort of a first generation electrified rock band. We were pretty pitiful by comparison. All we had were my marching band drum and Javier's little Mexican acoustic guitar. We used to peek over the fence to watch them rehearse.

One day their drummer wasn't there. "Hey, you, ojos de gato (cat eyes), across the fence. We know who you are. We've seen you've play with El Zoa. Want to sit in with us?"

I was thrilled. They accepted me immediately, replacing their drummer with his fancy snare drum and cymbal with me and my banged up, military snare drum and cookie tins. This became my first band, called the Sparks, with Lalo Toral on guitar, an American kid named Charles Lee on piano, and Ricardo Delgado on guitar and vocals. (Many years later in the 1970s, a band called Sparks became famous worldwide. I doubt they ever knew they had assumed a name that set teeny-bopper hearts to beating wildly in Mexico in the '50s.)

Soon the word was out and people in our neighborhood would pay us to perform at their parties. The other guys didn't share my passion for Fats Domino and Little Richard. They were copying what they heard on Mexican radio, which were actually white covers of the black records I listened to. In those days, much of America was still very segregated and black radio stations played black music for blacks and white stations played white copies for white audiences. They never told their listeners that Elvis Presley was copying Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup with "That's All Right Mama."

Along with the pesos we earned, I enjoyed the recognition. Our rehearsals were more like parties. Every time the band rehearsed, we had 10 to 20 girls sitting around the garage. When we got a job, Lalo and I, along with the rest of the band, had to push his piano down the street to parties, dragging it over pavement, battering it totally out of tune. But we didn't care. We were enjoying ourselves. We bought metallic pants with matching vests and considered ourselves unbelievably cool.

The music was still part of an innocent era in Mexico. In the United States, the beatniks were already bringing a serious touch to the youth movement, such as it was then. Later, it would surface on the streets of countries around the world. But we were still untouched. Rock n' roll was just starting to catch on and all kinds of bands were popping up all over Mexico City.

In 1958, when I was only 12, we got a record contract with RCA Victor covering American hits like "At the Hop" and "Oh, Carol." Unfortunately, Charles Lee, the center of the band, died unexpectedly from an infection just a few months after The Sparks started taking off, so I inherited the band and we went on to record two LPs for Columbia.

When Bill Haley and the Comets came to Mexico, my father immediately bought tickets for the whole family. It was one of the strongest impressions in my life. I was in shock. When I heard that music and felt that beat and saw those American guys rocking and playing the real stuff--so acoustic--so full of tonality and beat--it was absolutely beautiful. I went back to hear them three times. Haley, the grandfather of rock music in America with "Rock Around the Clock," was even bigger in Mexico. So popular in fact, that years later, when his star had faded in the United States, he moved the band to

Mexico City where many fans still loved him. He married a Mexican woman, played at one club for many years and went on making records in Mexico after he was all but forgotten in the States.

Before I was 15 great stars like Jerry Lee Lewis came to Mexico, along with other groups that weren't as well known. These people were gods to me. I just idolized them. I remember thinking: "We will turn into salt if we touch them."

Los Sparks after the death of Charles Lee

Everyone was in awe; my sister, even my father. We loved the music that America was coming up with. Elvis, of course, was not going to come to Mexico. He was too big.

My father, who was into hot rods and fast cars, made me an offer: If I got A's and B's for six months straight, he would get me an Italian moped, so I could go back and forth to school. It was the start of my love affair with motorcycles that has never ended. I also discovered girls during this period and the connection between the two has never left me.

Across the street from Colegio Williams was Colegio Madrid, an all-girls school, where I saw my first true love, a beautiful blonde named Maria del Carmen, who caused me to blush madly whenever I said hello. For a whole year, I would show off by riding my moped around her, but I never had the courage to ask her to go for a ride.

As I became more serious about my music, my mother began a small business in our colonia selling farm fresh eggs, which she would deliver by car. Our neighborhood was very supportive. They knew I was saving the money for real drums. With their help, plus money from grandmother Pilar, I finally got my first professional set of drums, my first Slingerland kit. Adios cookie tins, though I have to admit I got a pretty substantial start with those tin cans and the army drum.

At 16, I met Fernando, who everyone called El Tarolas--snare drum in English--but among Mexican musicians it was a nickname for a spastic, odd-duck kind of guy. He was a great pool player, a real ladies man and an adequate piano player who knew all the standards like "Misty" and "Tea for Two," as well as some jazz and a little rock and roll. He had a lot of contacts at coffee houses that were springing up as the beatnik movement spread to Mexico; places full of older guys from the National University wearing beards, playing bongo drums, worshipping Jean Paul Sartre and flirting with communism. Some even smoked pot, but I didn't want to know about it; it just didn't interest me. I was interested in jazz, which was coming on strong with groups like Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, and Dizzy Gillespie.

One afternoon I ran into Fernando in a park across the street from the pool hall which was his base of operations. He was all excited. "Fito, I got you a gig. I want you to come and play in this beatnik joint for me."

"I am too young," I told him. "They won't even let me in because you have to be over 18."

"Don't worry about it. They'll love you. You look good. You have talent. You're great on the drums. You have a thing for jazz. I want somebody who's not just a rock and roller. Come on, Fito, I'll show you a completely different side of music. I'm going to show you how I get a different girl every night and I'll take her home with me and she'll let me do anything I want with her. I'll also show you how you can make a lot of money playing music."

I hadn't really thought about music as a business, as a way to make money, but 50 pesos a day, about four American dollars, was good money for a kid, so the idea was very appealing. Better yet, the gig would give me chance to meet women. I still didn't have a sex life, beyond masturbation. I dated some girls, I kissed them, but that's as far as you could go in those days in Mexico.

Because I was under age, I wore a hat and dark glasses, not only to look like a beatnik, but to hide my face and help me blend into the crowd at the places where we played like La Faceta and El Ego, which became famous in Mexico City as the first coffee houses catering to intellectuals, rebels, poets, and other members of the avant-garde.

The club owners liked me; I seemed to fit in naturally, but because I was under age, the gigs were the start of a lifelong curse of being exploited when it came to getting paid. I'll never forget one club owner saying point blank, "I'll give you dinner, Fito, and let you drink a beer, but I'm not going to pay you as much as I pay Fernando." I wasn't about to argue. I was in heaven just playing and making what I considered big money for a 16-year-old who still lived at home.

By now, I was attending Colegio Franco Español and working toward a bachelor's degree in psychology, reading Fromm, Freud, Sartre, and Jung, and I was still planning to go on to the university. But I was having trouble staying awake in class because I was playing almost every night. I was in three different bands: Fernando's beatnik jazz trio, The Sparks in the colonia, and a new group at the school. I was fortunate though. When most students fell asleep in class, the teachers would throw erasers to get their attention, but in my case, some of the teachers would just go, "Shhhh, don't bother him" and let me snooze away.

The Sparks Fly in this Columbia Records promotional photo

My father, on the other hand, was starting to put pressure on me. He kept saying, "Don't play so much. You're grades aren't very good." He gave me such mixed signals. If he didn't want me to be a professional musician, why did he take me to see all those wonderful movies? Why did he buy me the instruments? I guess he figured, instead of me joining a gang, music would be a nice hobby.

Fortunately, many of the younger teachers had gotten caught up in the beatnik movement too, including my psychology teacher, my ethics teacher, and my philosophy teacher. They were all becoming regulars at the coffeehouses where I played. They were avant-garde people with a sensitivity towards my music and they knew that's where my energy went.

A number of them were homosexuals and they would show up in the cafes with their lovers. (AIDS didn't exist yet.) A couple of them came on to me, but I had a tantrum when one guy put his hands between my legs and that was it. They never pushed it. In some ways, Mexicans are very conservative about that stuff but in other ways they are looser, a little less prejudiced than in the States.

As my reputation grew and I started making more money, I realized that I didn't want to go on to the university. This was reinforced by Luis Maya, my logic teacher, who told me I was already a professional musician. He really appreciated my talent. I told him my father was getting on my case about my poor grades and he said:

"Forget about becoming a psychologist or a doctor because you are already on your way toward becoming a star. You are a pinche rocanrolero cabron." (Loosely translated, it means a fucking rock and roll sonofabitch, which he meant as compliment.) Forget about going to the university because you're not going to find the same sympathy and support there. You are going to be a drummer and you are going to be a great musician. Don't worry about your grades. I'm going to pass you and you'll get your bachelor's degree."

But not all the teachers were that helpful. My problem with my literature teacher wasn't because she was demanding or cruel or a monster. In fact, she was a good-looking woman with great legs, so when I wasn't fighting to stay awake in class, I'd stare at her legs and daydream. One day, in the middle of a daydream, I was called to the principal's office.

The principal was Señor Carriedo; a very stern, but handsome man of French and Spanish descent. He was sitting at his desk in a hand-tailored English Saville Row suit.

"Please sit down."

I'm thinking, "Shit, this is it. Something terrible is about to happen."

"I understand you have some outstanding talents, Mr. de la Parra."

Did he really say "outstanding talents?"

"I was wondering if you could do us a great favor and perform with your band at the graduation dinner. There are going to be several prominent senators, who are the padrinos (sponsors) of the graduation, plus Mayor Uruchurtu. With such illustrious guests, I feel the school should put on a first-class program."

I couldn't believe it. This guy didn't call me in to give me a hard time, he called me in to ask a favor. In the back of my mind I thought: now I've got him. Since I play drums in both school bands, neither group can play without me. And if I'm not there, there won't be any music. Sure, they can hire a marimba band or a conventional businessman's bounce type of band, but the kids don't want to hear that. The kids, the senators, the mayor, everybody wants to hear the now-famous rock and roll band from the Colegio Franco Español--of which I am the drummer. So I'm thinking: Go for it. What the fuck?

I quickly said: "I would be delighted to play for you, but I'd like your help. I'm having a problem with my literature class. I need to pass. I need to get my degree." (Mumbling under my breath, the fact that I was unable to take the final.)

"I'm sure something can be arranged," the principal smiled.

At that moment I realized for the first time I could use my art as a weapon. Being a musician gave me power. My talents were worth something.

I got an "A" in literature and after the graduation dinner, my logic teacher, the one who called me a fucking rock 'n' roller, signed my menu "with great pride and joy in his artistic sensitivity" and told the band: "You boys have it made. We make people think. You make people feel. That is much more important."

At that moment, I knew for sure my career was music. It was the point where I broke from the establishment, from my father's expectations, from the pressures of my family to go to the university.

There I was, fresh out of college with a degree in psychology, and the '60s were dawning. From Paris to San Francisco, young people were making their presence felt throughout the world and Mexico was no different. The blooming rock revolution in the United States was spilling over into a thriving rock scene south of the border; underground cafes were springing up even though this was a period when rock n' roll was constantly banned and suppressed by what we called el dèspota gobierno (the despotic government). To the officials, these clubs were hotbeds of revolution instead of college student hangouts.

From the late '50s up until the late '60s, any minor incident--an accident in the kitchen, a complaint about somebody parking a block away, things unrelated to our youth subculture or our music--would trigger a wave of raids on the coffee houses. Gangs of police would burst through the doors and grab everybody in sight--owners, performers, employees, the audience--throw them into paddy wagons and take them to jail. Some of the plainclothes cops saw me so often they got to know me. Once, they even arrested everyone else in the place but ignored me, leaving me alone with my drums in an empty room as the police wagons pulled away.

The cafes were actually quite innocent and the audiences for the most part were law-abiding kids. Their only sin was to be young and to be there. But the city government was convinced the coffee houses were filled with viciosos (drug addicts) and subversivos (subversives). Of course that was nonsense. In the early years, pot was occasionally sold on a small scale by individuals but real drug dealing didn't happen until the late '60s. It was a while before Mexican kids got into drugs like their American cousins.

The real subversivos had their own hangouts where they could plot in peace; they didn't want musicians around making noise that interfered with their conversation. They also weren't about to pay the kind of prices the music-hungry kids would tolerate for an espresso or lemonade in order to listen to some rock music. The revolutionaries could buy a gun and a stylish set of fatigues for what the cafe owners charged a young couple for an evening's entertainment.

Even dancing was estrictamente prohibido. It was really pathetic to play for an audience sitting at tables, doing the jerk or the mashed potato in their chairs, hands waving and necks spasming back and forth, unable to stand and move their feet without being thrown out. Mexicans called this sickening abuse of authority guarurismo. Each government official brought in his friends (guaruras) and gave them some of his power. Then, they brought in their friends and did the same.

One day a promoter asked The Sparks to join a tour with a big Las Vegas-like variety show that included a comedian, dancing girls, a magician and a band. We jumped at the idea, but El Zoa's parents didn't want him to go. When he showed up to join us, we asked him how he pulled it off. He smiled and said, "I went to the store to buy a loaf of bread and I just didn't go back home."

The performers, all top-flight acts, were on a level with the best rumba and salsa bands around. The tour lasted about a month and we worked six nights a week until 1 A.M. for about 50 dollars a night. Along with improving my musical skills, I learned to live on the road, to get along with other people, to deal with all the problems of a traveling troupe. At that age, you don't feel the strain. You don't get sick. If you do, you get better in a couple of days. You can go without sleep. You're a lot more resilient. Even with the hardships, it put the worm in my head that this was the life I wanted to lead, full of experiences, adventures and danger.

There was a lot of wild sex going on in the troupe, but because we were so young and very naive, the other entertainers ignored us--with one exception. One night while I was on stage, someone stood behind the curtain and started giving my back a massage through the drapery. As I continued to play, the hands dropped down to caress my ass and my legs. I was dying. Between beats, I'm whispering: "Please, cool it. Don't do this to me." It was very embarrassing. To this day, I don't know who it was. I suspected, or maybe hoped, it was one of the pretty dancers I sometimes heard giggling backstage.

On another evening, when I was heading back to my dressing room, I was stopped by a distinguished, good looking older gentleman, who was either an agent or a manager, the type that everybody treated with great respect. Out of the blue, he said: "You are going to make it. I have made stars and I have seen them come and go. You will be a star. I just wanted you to know that." Then, he disappeared. It was amazing. I never thought about stardom or gave it any importance.

By now it was the early '60s, The Beatles had swept away the first generation of American rock stars and I was getting even deeper into music. For the first time, I was taking lessons. Before that, I was a natural drummer, playing by instinct or copying what I heard on the radio. Now, I wanted to learn the basics like how to read music. I also started to talk to different drummers, some famous and some not, who performed on the same bill with us. Unfortunately, most of them looked at me as competition rather than as a student, so they weren't anxious to give away any trade secrets.

A notable exception was Vincente Martinez, El Vitaminas. A great jazz drummer, he was a short, funny little guy, very dark and Indian looking with greasy hair. He didn't really want to help me either, but I kept pestering him to teach me how to read music and understand some of the basics like the value of notes. Finally, in exasperation, he grabbed a newspaper, held it up and said: "This is a whole." Then he folded it in two and tore it. "These are two halves." Then he took the two halves and ripped them in half, and then again. "These are four quarters and these are eighths." He kept on until the paper was in shreds. Then he lit up a joint and glared at me: "Don't bother me with this shit. Don't worry about it. Just think of it that way."

This was my first and only formal music lesson.

Music was becoming an important part of my life--more than I ever expected. While the original appeal was the glamour and the idea of getting girls, I now realized there was something much more important and difficult about playing an instrument, about expressing emotions through music, about being an artist.

I immersed myself in jazz because that's where the great drummers were: Joe Morello who played with Dave Brubeck, Art Blakey with the Jazz Messengers, Elvin Jones with John Coltrane, and of course, the masters: Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich.

Another tutor was a handsome, fair-haired con artist from Argentina who I knew only by one of his many aliases, "Miguel Casis." He was an ex- con straight out of the movie "The Great Imposter." He was funny and charming and as good looking as he was crooked. He drank a lot, laughed a lot and could convince anybody of anything. He assembled a whole caravan of artists, including me and The Sparks, and decided to go on the road to do "benefits" for the Red Cross. He'd ask the local officials to cover expenses and he'd take care of the publicity that would entice people to donate money. While he told everybody they would make money, we received very little. He kept most of it.

One of his most famous promotions was "the kilometer of pesos," which in those days meant something because one-peso coins were actually made of silver alloys, like old-fashioned American silver dollars, but bigger and heavier. Donors were asked to lay pesos in a line that stretched across the stage of the theater where we played. Of course the "kilometer" never got past about 50 feet because the minute the crowd was out of the theater Miguel pocketed the pesos.

He not only stole from ordinary citizens, but as we wound our way around Mexico, he would organize poker games for provincial bigshots, like the governor of Veracruz, the mayor of Orizaba, and the owner of the Cerveza Moctezuma brewery and he would cheat, using signals and various tricks with his partner, a plump, pig-faced, so-called attorney. Sometimes he stayed up, drinking and gambling and whoring, for three or four days in a row. Then he would collapse for two days, ignoring the phone and knocks on the door as he slept before starting the cycle all over again.

One evening in Tierra Blanca near Veracruz, he came up to us as we were sitting outside the hotel. "Come on, you guys, we're not making any money (a lie, he simply kept it all), but at least we can have a good time. How 'bout a bottle of rum for everybody, all the food you want, and everybody gets laid?"

Of course, we all answered "Yeah, yeah."

Miguel said he'd found a gordita, a nice little fat girl.

The guys pepper him with questions. "Is she pretty? Is she nice like the ones you always get?"

"Let's just say she's a gordita and she'll take care of all of you."

She was and she did.

We went to her house where she was waiting in bed with a nice, big smile on her face. She fucked all five of us. One after another. We each were with her maybe four or five minutes, max. He probably recruited her earlier at a local whorehouse. She had a pretty face and a very nice, relaxed manner. God knows what Miguel promised her for screwing the whole band. Whatever it was, I doubt he ever gave it to her.

While I disapproved of the way he cheated people, I did learn from him that there's a certain magic in life, and that it's possible to accomplish the impossible through the power of charisma.

A few weeks after the tour, he was caught by the police in Mexico City and thrown in jail. They found five different passports on him with five different names. He was wanted in several countries in South America and that was the last we heard of him. He was the first, but not the last, guy who came into my life like that--a charming crook who melted away after awhile, without my ever knowing his real name.

Like the music, there were some movies that also changed our lives in the '50s: "Rebel Without a Cause," "Jailhouse Rock" and for me, like a lot of other motorcycle-crazed youth around the world, "The Wild One." I had to have a bike, a real one, not an Italian moped. With a loan from my grandmother Pilar I bought my first true motorcycle, a 1959 Triumph Bonneville, much like the bike Marlon Brando rode in the movie. And just as rock music had become an instant passion for me, I realized that motorcycling was going to be part of my life forever. I was so jazzed I actually slept next to the bike for the first few nights.

This period was one of the best times in my life with my friends, my music and my motorcycle. I joined a popular band called "Los Juniors" and two of our records made the Latin American Top Ten Chart. Then I joined "Los Sinners," already famous with several hit records and known as a "quality" band. They also rode motorcycles, so we naturally developed long-lasting friendships based on our love of bikes and rock n' roll.

The lives of two friends from Los Sinners, Tony de la Barreda and Ramon Rodriguez, would crisscross mine many times in the years ahead, often painfully. But at that time, we were too busy being kid rock musicians to think about the future.

Los Sinners attracted other kids on motorcycles to the coffee houses where we played, turning them into biker hangouts much like the ones I was going to spend a lot of time in, in the years to come. It was all very innocent, no drugs, no crime, and pathetically little sex--just nice kids, hanging out and having a good time.

By now, I was in a top local band, had a motorcycle, had lost my virginity, was a key figure in the biker hangouts and now I was about to score another first that was the start of a lifelong pattern--my first American girlfriend.

In the summer of '64, Kathleen and her friend Carol were Harvard students attending classes at the National University in Mexico City. They were cheerful, intelligent, sexy and they liked motorcycles and rock n' roll. Kathy was tall, blonde, and beautiful with a figure that had my friends rolling their eyes and biting their lips in anguished envy. At 19, she was a little older than me and when it came to love-making, she was a lot freer than Mexican girls. She was my first serious affair with a first-class woman, the first I ever knew. I fell madly in love. I would have proposed to her if she had ever come back to Mexico City, but she went on to a very successful political career in the States.

With Kathy gone, my motorcycle turned on me too. Although it was fast and looked cool, the Triumph was a mechanical nightmare, infuriating my family because it leaked oil all over the garage and driveway of our house, and maddening because it regularly broke down. It was my only form of transportation and life turned into a series of missed gigs or late entrances in dirty clothes. My dates often ended with angry, oil-splattered girls snarling at me by the roadside because they would have to take the bus home hours after their parents' curfew. With a river of pesos flowing straight from my wallet into the hands of the local Triumph mechanic, I frequently ended up traveling by bus or taxi, which I couldn't afford now. Much as I loved the Triumph, it had to go.

Kathy, my first American girlfriend, on my first real motorcycle, a 1959 Triumph Bonneville.

I took the first offer I got and ran all the way to the local dealer in BMWs, motorcycles famous for reliability and class, to buy a brand new R60. The dream was on again. I could actually wear a tuxedo to the gigs and arrive impeccably dressed. I rode the bike for thousands of miles, day in and day out. It never failed me. It was the start of a life-long affair with boxer-engined BMW cycles.

I was about 18 when I accepted an offer to join one of Latin America's most famous bands, "Los Hooligans." They had an impressive career with several gold records and enjoyed wide recognition in Spanish speaking countries, so I was amazed to discover that they were actually bad musicians who played the bouncy, childish crap that came to be called "bubble-gum music."

This was my introduction to a cruel truth in the pop music world: sometimes the worst bands are the most successful, while talent, taste and hard work go unrewarded. Welcome to the music business, Fito.

In 1964, Kathy, who was back at Harvard, sent me a couple of Jimmy Reed records, along with one called "Saturday Night at the Apollo Theater," featuring various black artists. I also got hold of some James Brown and Ray Charles, which really impressed me. Those early R&B records of my sister's, my growing education in jazz, and the black music Kathy turned me on to brought me to a crisis point.

My changing taste made performing with Los Hooligans intolerable. The money and applause wasn't enough to make up for the infantile, commercial music, the frozen smiles, the silly choreographed steps in our red or blue coats and white patent leather shoes. I could barely go through the motions, not after listening to the records Kathy sent me. She broke my heart because she never came back, but she did leave me that legacy.

One night when I was playing in a cafe called El Sotano (the Cellar) with El Tarolas, Javier Batiz showed up and we invited him to sit in. Javier was a singer and guitarist who became a rock star in Mexico for generations; he's one of the best ever, but he just never caught on in the States. He had a raspy blues voice, sang only in English and played guitar like BB King, skills forged by long nights playing in Tijuana, where he had to satisfy audiences filled with black American sailors and Marines.

Up there on the border, Javier taught guitar to a young kid nicknamed El Apache, because that was the only song he knew at the time. Sitting beside Javier, he learned his first guitar chords. Later on, the kid did okay on his own--not as El Apache but as Carlos Santana.

Javier changed the whole scene in Mexico City by doing a lot of Jimmy Reed, BB King, and Ray Charles. He taught us that there was something beyond what the commercial media was giving us, something with more soul.

While I instinctively liked his music, many of the other musicians didn't get it. They were convinced that Mexico City audiences would rather hear imitations of English pop bands like The Beatles, than the hard-edged black American sounds that came from that crazy pocho Javier Batiz.

Sick of the pop scene, I quit Los Hooligans and joined The T.J.s, a hard core rhythm and blues band that backed Javier in Tijuana. But I kept a hand in with Los Sinners, the band I felt most comfortable with. They were just like me: middle-class kids who rode motorcycles, from the same part of town who had gone to the same schools .

One October night in 1964, at a gig with Los Sinners at a cafe called Milleti, I hit two milestones at once: I met my first wife and went to my first orgy.

Sonja came into the club looking very square in her American-coed outfit, a powder blue skirt and pastel blue sweater plus nylons and white ballet flats. I had just given up hope that Kathy would ever come back and here was another gringa, but a much different one, quiet, straight, a nice Baptist girl from Phoenix with blonde Barbie-doll bangs and an open, clean-cut face. Like Kathy, she was a college student. She went to the University of Redlands in California and was taking language courses at the National University.

I had never met an American girl like her before, so pure, so genteel, so sweet. She fascinated me. At the end of the evening one of the cafe owners invited us to a party, so I talked Sonja and her friends into coming with us.

Suddenly, one of the guys at the party turned to me and whispered in my ear: "You might want to take your gringa friends home pretty soon. See those two chicks over there? They're going to put on a show for all of us. Then they are going to fuck every guy here. If your friends are as innocent as they look, this isn't their scene."

I grabbed Sonja by the hand and headed for my motorcycle. "Time to go home," I said, pretty firmly.

When I kissed her good-bye, she clamped her lips tight. She didn't know how to kiss. In fact, I learned later that she had never kissed anyone before. Although I liked her a lot, under the circumstances it was not something I wanted to pursue right then.

I wanted to get right back to the party.

It was ironic that at the same time I met this lovely, young saint, I was leaving her to scramble back to an orgy. It was a sign of things to come. An awareness of the darker side of the musician's life was already growing in me.

By the time I got back to the apartment, the two women--both very attractive Latinas--were nude on the carpeted floor. One looked a little reticent, like she had never done this before, but the other was going totally nuts, rubbing and licking her all over. They were surrounded by more than a half dozen men, who were stroking themselves and encouraging them.

The shy one came with a wild scream, then began giggling and laughing: "I'm a bad girl. Oh God, am I ever a bad girl."

Watching them excited me in a way that I had never felt before, and when they finished with each other, they did all of us. It was just like the gordita in Tierra Blanca. We lasted barely two minutes each.

Our quick performance couldn't have been much of a thrill for them after the terrific time they obviously had with each other. But, they appeared to like us, the innocent kids in the band. Since we'd been more than properly taken care of, we headed home to sleep.

We didn't know yet that we were supposed to go on all night.

A new girl (Sonja my future wife) on a new bike (my first BMW, an R60)

Los Hooligans (sic) holding one of many gold records from Orfeon.

At A Tardeada: Tony & Emilio de la Barreda, Fito, El Topo, Javier Florez "El Zoa"

Los Hooligans: Agustin Islas, Fito, Johnny Ortega, Humberto

Cisneros, El Cuervo