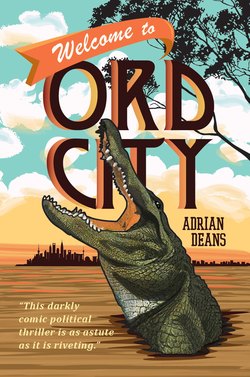

Читать книгу Welcome to Ord City - Adrian Deans - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Happy Land

of the Fat Sharks

‘Six minutes,’ said Ah Cheng, chewing his knuckle and dripping with sweat. He always stank of sweat and, in Asif’s opinion, the rose water he splashed over himself to hide the smell just made it worse.

‘Plus extra time,’ said Asif, then laughed as Ah Cheng winced at the reminder.

‘Be serious for once,’ growled Razzaq. ‘We’re not here for the football!’

He’d kept his voice low but he needn’t have bothered. Peril matches at Rinehart Stadium were always a sell-out and when 60,000 fans were all screaming their encouragement with the home team a goal down and six to play, Razzaq could have shouted at the top of his lungs.

Asif always sat between the two older men. They were older, but he’d been in Ord City, in the Temporary Citizenship Zone, the longest. Asif was part of the First Wave and in less than two weeks would be eligible to leave the TCZ and go anywhere in Australia, like any normal citizen.

‘You have the data?’ asked Razzaq, and Asif nodded, as the Melbourne Victory players repelled yet another Ord City attack with their tightly organised defence.

‘Asif!’

Razzaq was glaring and Asif, with an effort, turned away from the game and went to pass the data stick to Razzaq.

‘Keep it for now. But we need to talk about your mission … again. Explain the details of the plan … starting from the moment you are allowed to leave Ord City permanently.’

‘The Node is forty kilometres south at the Argyle substation,’ said Asif, ‘On the day of the mission, drive south along the Argyle Highway until …’

At that moment the Rinehart Stadium erupted with joy as their beloved Horace Hung Feng controlled the ball with his chest at the far post and drilled a shot into the roof of the net from an impossible angle. Ah Cheng leapt to his feet in unison with 60,000 other supporters and started singing the Feng Song.

Razzaq was furious.

‘Fuck Feng!’ he shouted. ‘Fuck the Pilgrims and fuck you Cheng … we have serious business!’

Ah Cheng nodded, chastened, and resumed his seat, while Razzaq fumed and the crowd returned to its standard level of excited buzz. The Melbourne Victory players kicked off again – two minutes left to play.

‘Continue,’ said Razzaq, and Asif took up from where he’d left off.

‘South along the Argyle Highway until the turnoff. There is no sign but it is exactly 14.9 kilometres past the turn off to Halls Creek.’

‘You have no authorisation to take that road,’ snapped Razzaq.

‘No,’ agreed Asif. ‘If I am questioned, I took the road by error … but the warning signs were in English. How was I to know it was a prohibited road?’

‘How far do you drive?’

‘Three point seven kilometres from the Highway there is an outcrop of low rocky ridges with several indentations big enough to conceal a car.’

‘From this point,’ said Razzaq, ‘there is no chance of escape if discovered. You must protect yourself.’

‘I will have an old Australian army Stehr pistol and four ammo clips.’

‘But if capture seems inevitable?’

Asif grinned, watching the game, and held an imaginary pistol against his head.

‘What do you have in your satchel?’ continued Razzaq, as the crowd started rising again. The Pilgrims were probing about the Victory box, the referee looked at his watch.

Asif tore his eyes away from the game and regarded Razzaq – an angry little man in a yellow tee shirt and white skull cap who worked in a stir-fry restaurant and always smelled of cooking oil. But he was head of the Tong and had to be taken seriously.

‘I have six sticks of … ’

The stadium exploded with sound and fury and Asif’s head whipped back to the action. The Pilgrims (known to most supporters as the Peril) were clustered in a tight celebratory knot by one of the corner flags and the crowd were on their feet dancing once again. Ah Cheng had raced to the front of their bay where the more active support were clutching at each other and writhing in an orgiastic outburst of adoration.

Razzaq’s face was twisted with contempt – eyeing Ah Cheng in disgust.

‘I’m glad it is you and not Cheng who carries the burden of our mission,’ he said. ‘If he was forced to choose between …’

‘Cheng is solid,’ insisted Asif, ‘and he sees the football as symbolic of our struggle.’

‘He does?’

‘Cheng says the Ord City Pilgrims have infiltrated the A-League and are successful. Ordinary Australians deeply resent the loss of face when we Asian invaders take points off them but deep down they know of our inherent superiority … especially in spiritual matters.’

Cheng had indeed said all of that, but he’d said it in the mock-fanatical voice he used for mimicking Razzaq, when Razzaq was not present.

Razzaq looked thoughtful.

‘I still say he is dangerously distracted by football. If we changed our objective from the Node to this stadium … do you seriously believe Ah Cheng could go through with it?’

Asif watched Ah Cheng dancing with the active support as the referee blew full time and felt a wave of affection for his Chinese friend. He knew absolutely that Ah Cheng would violently oppose any plan that jeopardised his beloved Pilgrims, but he said: ‘Ah Cheng is a member of the Tong and has fought our fight for many years. We should not doubt him.’

‘Maybe not,’ said Razzaq, ‘but we will watch him. Too much love of Peril is not good for a man.’

• • •

Asif loved the feel of his neighbourhood.

As he walked home after the game, assailed by the energy, sights and smells of District 11 (also known as K Town after the old Kununurra) he reflected upon his amazing fortune.

Asif had arrived in Australia from Bangladesh in 2022. His family had been forced out of their fishing village by rising sea levels – the floods had become increasingly regular until the water never left. Asif’s village was under two metres of water and the movement of vast numbers to higher ground had caused friction and put a lot of strain on the land that was left. Like so many other unmarried sons, Asif was given the task and the duty to get to Australia and commence a new life in a safe and lucky land where he might re-establish the family.

The journey had been hard, and very expensive. It was easy enough to get to Jakarta and there were any number of boats heading for Australia. The prices charged were crippling – the equivalent of two years wages in Bangladesh – but the family had provided the means and were depending on him.

He managed to find a berth on a ramshackle fishing boat which left the port of Surabaya with nearly seventy refugees aboard, including families with young children. The boat should probably have carried no more than twenty so was dangerously overloaded and very low in the water with the bilge pumps straining to keep the vessel afloat. Fortunately the sea was mild but there were dark clouds to the south.

An hour after departure, when it was impossible to leave the ship and swim back to shore, the captain addressed them all. His friendly pre-departure demeanour was entirely gone and, with an evil grin, he held up a hessian sack.

‘I have here your passports,’ he said, then, without another word, tossed the sack overboard.

Immediately the boat was filled with wails of outrage and despair but the captain just laughed as his two colleagues produced automatic pistols, and the wailing ceased.

‘You learn quickly,’ he approved. ‘That augurs well for your chances of survival.’

He went on to explain that if the Australians knew their true identities and nationalities it made it much easier to send them home. He told them all to choose new names and invent themselves a history. It was simple enough to tell a story of persecution – none of them needed to invent such a story – but the harder it was for the Australians to check their stories the longer they would stay in the country. And with so much international condemnation over Australia’s treatment of refugees, there were rumours that the Australians were about to change their laws.

‘It might soon be easier … it might soon be harder to get residency … who knows? But unless you’re actually in the country you have no chance.’

Asif had brought adequate food and water for the voyage but it was stolen on the first night, so he was obliged to survive on handouts which were grudgingly given and very poor. There was no toilet aboard (except for the crew) so the passengers all pissed and shat over the sides – fathers clutching their children with an eye on the following sharks.

‘Sharks in the water, sharks on board … and sharks at home,’ said Noor, an Afghan Asif had befriended in Jakarta.

‘And sharks in Australia, no doubt,’ said Asif.

‘Perhaps,’ said Noor, ‘but from what I hear they are fat and slow … we will make a good life there, my friend.’

‘So much effort and danger,’ laughed Asif, ‘to get to the happy land of the fat sharks.’

The Australian sharks were not fat and slow. On the third day out from Surabaya a patrol boat had appeared out of the storm murk from the south, as the waves freshened and the wind and the children started howling. The patrol boat sliced through the water as the sharks had done, circled the boat once with two large machine guns trained on them, then a voice thundered from a loudhailer like a shout from hell.

At that moment the fishing boat shuddered and seemed to stop.

‘The captain has scuttled us,’ said a white-faced Noor. ‘Let’s hope the Australians are merciful.’

The captain, wearing an inflatable jacket, fired a distress flare, laughing as the heavens suddenly opened and panic swept the sinking boat.

‘Listen to me,’ shouted the captain. ‘I am not the captain of this boat. The captain was Bamban Sulo who lost his life trying to save this ship. Is that clear?’

There was confusion among the passengers, so the captain explained again, emphasising his words with a pistol.

‘The brave captain, Bamban Sulo, fell overboard while trying to repair the hull. Anyone who tells a different story will receive their punishment in the camps where I already have friends and weapons. Is that understood?’

Waves were beginning to wash over the gunnels and a large fat woman went shrieking over the side, pulling a small child in with her. Without thinking, Asif leapt into the water, swam hard for the panicking woman and tried to calm her as she clutched frantically at his head and shoulders. The child was fine, clinging to her mother’s neck, and just as Asif remembered the sharks and his foolishness in entering their domain, a black rubber dinghy appeared next to them and hands reached down to pull them to safety. It took nearly a minute to get the woman into the lifeboat, even with Asif pushing from below, and that was the time he felt most vulnerable – moments from safety but feet kicking madly to attract evil from the depths.

On board the Australian warship they were given blankets and a hot meal and taken to Christmas Island, which he expected to be just a respite, but they were there for many months. Always there were rumours that they would be sent to Nauru, or New Guinea, or even a camp on the Australian mainland. They spoke occasionally with officials and lawyers – always the same questions, as though being tested for consistency to reveal a lie. Asif, despite the warnings of the captain had told the truth about himself. Noor had told the truth about everything, including the captain. This was a serious mistake. Noor may have hoped that his revelation of the captain’s behaviour might stay secret, but the captain found out almost immediately and stared at Noor with black-eyed vengeance. Two days later, Noor was found in his cot with his throat cut, but the captain had been in the discipline wing and was clearly innocent. Of course, everyone knew he had ordered the killing, and when he was released from discipline a few days later he was immediately established as king of the camp.

It was in the camp that Asif discovered Habal Tong. HT wasn’t really a religion – it welcomed members of any religion. It was more a set of precepts and values that, on one level, encouraged tolerance and unity. But on another level, effectively radicalised and galvanised anyone who felt slighted, insulted or in any way disadvantaged by the Australian mainstream.

The HT group were aloof from the rest of the camp, including the captain’s thugs. In fact, they were the only ones the captain’s thugs left alone and despite the fact that Asif wanted, desperately, to embrace all things Australian to improve his chances of staying permanently, he found himself inexorably drawn to them. ‘All is nothing and nothing is all,’ was the most profound and fundamental maxim of Habal Tong and Asif reflected on it constantly – reconciling it with all his previous beliefs and feeling its empowerment.

Somehow the maxim was also interpreted to mean that Australia, as a wealthy first world nation, owed all refugees a living. ‘It is the so-called first world,’ sneered Tee Tee, the head of the Tong in the camp, ‘that caused the sea levels to rise with their industrial exhalations. If they take away your land then by all that is just and right they must provide an alternative. And if they will not do so willingly then we will take what is rightfully ours.’

It was a powerful argument but unpopular with the Australian officials who had made life so difficult for Asif – never believing him but always lying to him about his status and his prospects for staying in Australia.

‘I call on you, brothers,’ Tee Tee would say. ‘I call on Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Tamils, Muslims, Buddhists, Shinto, Confucianists, Falun Gong and Bahai … even Christians … to embrace the Tong with all your heart. This is no apostasy to replace your birth religion. No. It is a prism to focus the elements of all religions and fuse them into something more … to strengthen your own faith and bring you into a wider brotherhood!’

The turning point came in 2023 when the law changed. After so much international and domestic criticism, the Australian government simply gave up on their various policies to scare refugees away. All in the camps were given seven year temporary visas with a major restriction. They were not allowed to leave the Temporary Citizenship Zone (the TCZ) for the whole of the seven years. If they did, they would immediately be deported. And if they returned the seven year clock would start from scratch.

By the time Asif received his visa, he had been in the camps nearly two years and had been radicalised into hating Australians with their wealth and their privilege and their different rules for different people. He was a hardened member of the Tong and one year later had been easily recruited into a deep cell – biding its time to take revenge on the country that had treated them with such contempt.

‘That was a while ago now,’ admitted Asif, as he climbed the stairs to the apartment he shared with Tanya – the best part of his good fortune and the source of his growing regret.

‘Did they win?’ she called as he opened the door.

‘Pardon?’

Tanya was tall and blonde – the light to his dark – and, as ever, he found himself dazzled and took a few moments to adjust.

‘Oh … yes. Two, one … but they left it very late.’

‘That must have been exciting.’

She kissed him on the nose and walked back into the room from which she had emerged when he opened the door. Asif poured two cups of chai from the pot she had prepared in anticipation of his return and followed her into the best room of the apartment.

Tanya’s studio was supposed to be the living room, but the walls were covered with her strange paintings. The large table was invisible under paints and brushes, but also the clays, wires and bric-a-brac of her various sculptures. And empty water bottles. Like most Australians, Tanya didn’t trust the water in Ord City. Even the chai was made with bottled water.

Around the room were easels set up with paintings at various phases of completion. Asif found a place for her cup and sat back in the battered old armchair holding his chai in both hands. Tanya herself was a work of art – beautiful and complex, and utterly beyond his previous experience of women.

‘What are you working on?’

Tanya picked up her cup and eyed him over the rim.

‘You.’

‘Me?’

‘Yes … what do you think?’

She indicated one of the larger canvases which was split in half by an oblique line, dividing two different scenes. One was a flat red desert, and the other was a chaotic ocean of colour and shapes only partly perceived.

‘I don’t understand it.’

‘I think you could if you tried.’

‘I am trying. How can such a strange painting be me? It looks nothing like me.’

‘It’s how I see you.’

Asif looked again at the painting, trying to see what she saw.

‘It’s half desert and half chaos,’ he said.

‘Exactly … just like you.’

Asif was shocked, but also intrigued.

‘How am I a desert?’

‘There are several ways,’ she replied, taking a sip of her chai and contemplating her work with fresh eyes. ‘For a start you are hot and dangerous.’

‘So is lava.’

‘But lava is flowing … you are solid, hard, unmoving.’

‘Unmoving?’

‘And there is mystery about you … an infinite mystery.’

Asif glanced at her, conscious of the data stick in his pocket, but she was still gazing at the painting, as though discovering new insights.

‘What about the other part,’ he asked, ‘… the strange shapes and colours like a breaking wave?’

‘That is also you,’ she said. ‘Wild, explosive, overfilled with energy … ’

‘It looks like the wave will swamp the desert and wash the sand away.’

‘The wave can never swamp the desert,’ she replied. ‘The desert is too great.’

‘So the chaos can never wash away the sand to reveal the mystery lying beneath.’

She turned and smiled at him.

‘You see?’ she said, standing up and taking him by the hand. ‘You do understand the painting.’

• • •

Later, as his heart beat slowed, Asif was staring at the ceiling in the semi-darkness, still seeing the painting in his mind’s eye – the deep reds of the desert and the striking blues, pinks and greens of the ocean.

‘It’s more than just me,’ said Asif. ‘It’s us.’

‘What is?’ she murmured, her eyes closed.

‘The painting … it’s both of us.’

‘You think so?’

‘Of course. We are a contrast but also a coming together of different lives and cultures.’

She was silent for a while and he thought she had fallen asleep, but then she said, ‘We’re not so different. We share the same values.’

Asif was immediately confronted with a vision of Razzaq’s angry face. Tanya shared his Habal Tong philosophy but knew nothing of the cell.

‘Mostly,’ he agreed.

‘Not mostly,’ she laughed, ‘… totally. I couldn’t love a man who didn’t share my values and I know you do.’

‘But what about our work?’ he said. ‘You create and I destroy.’

‘You’re being deliberately superficial,’ she chided. ‘You don’t destroy. You mine minerals to create the basis for modern life.’

‘Through destruction … and I enjoy destruction.’

‘You create also … in the most important ways imaginable.’

‘I’m not very good.’

Since he’d been with Tanya, Asif had tried his hand at sculpture – carving and polishing the oddly shaped lumps of silvery magnetite he brought home from the mine and releasing their inner lives and beauty.

‘You’re better than you know,’ she said, then changed the subject.

‘When you get your citizenship, we should go to Sydney.’

‘What?’

It was a bizarre idea. Sydney was a mythical place – the Emerald City in the Land of Oz.

‘To live?’ he asked.

‘No … at least, not yet. I haven’t finished my work in OC … and there aren’t too many mining jobs in Sydney.’

‘Then why go there?’

‘Because Sydney is where I come from. My family are there and I’d like you to meet them.’

‘I’d like to meet them also,’ he agreed, with a sinking heart as he remembered his own family back in Bangladesh. He had sent money over the years but they had never accumulated enough to bring the whole family to Ord City. His mother could have come. His younger siblings could have come. But always they wanted more money so the entire extended family of aunts, uncles and cousins – half the displaced village – could all come out together. And in the meantime, the money was spent on survival.

‘Will your family like me?’ he asked.

‘They already like you,’ she said, snuggling her bottom up against him and moments later her breathing was long and deep.

Asif enjoyed several seconds of indescribable bliss as he basked in the glow of his love for her.

Then he remembered Razzaq.