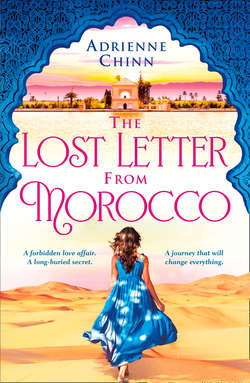

Читать книгу The Lost Letter from Morocco - Adrienne Chinn - Страница 10

Chapter Four

ОглавлениеThe Road to Zitoune, Morocco – March 2009

The tour bus rattles across the plains of Marrakech. A wall of towering snow-capped mountains thrusts skywards at the edge of the olive groves spreading out over the plains like a green sea to the right of the road. The March sky is achingly blue. Addy unzips her camera bag. She takes out her camera and the 24–105 mm zoom lens, changes the lens and screws on the polarising filter and lens hood. Leaning out of the window, she braces her elbows against the window frame.

As the bus bounces along the potholed asphalt, she snaps pictures of the squat olive trees, cactus sprouting orange prickly pears, and green fields dotted with blood-red field poppies. Towns of pink earth buildings materialise from the land, lively with mongrel dogs chasing chickens, women riding donkeys and men with prune-like faces shooing flocks of sheep.

The sun is warm on her face and her naked arms. She settles back into her seat. The faded blue vinyl is ripped at the seams and burns her hand when she touches it. She fans her face with her straw hat. Philippa’s voice rattles around her head: Are you mad, Addy? You’re probably suffering from post-traumatic stress or something. A woman alone in the Moroccan mountains for three months? You can’t be serious.

Philippa had obviously missed the envelope of Polaroids. Missed the photo of Gus and Hanane and the letter. She’d have said something, definitely. Gloated. Anything to show up their father as a feckless, irresponsible wanderer, leaving abandoned women and children in his selfish wake. That wasn’t the father Addy knew. The doting father she’d adored. But who was this Hanane? Why was she wearing her mother, Hazel’s, Claddagh ring? Why had their father never said anything about Hanane and the baby after he’d come back from Morocco? Surely he wouldn’t have just abandoned them. But he’d done it once before, with Essie and Philippa, hadn’t he?

Maybe she and Philippa had a Moroccan brother or sister living in Morocco. A twenty-three-year-old now. Surely someone in Zitoune would know where Hanane and her child were now. Once she’d found out what had happened to them, she’d let Philippa know. That would be soon enough.

She leans her head against the vinyl seat, the bumps and sways of the bus lulling her into a dozy torpor. Nerves flutter in the pit of her stomach. Just three months. Three months to see what she can find out about Gus and the pregnant Moroccan woman in the photograph. Three months to work on the travel book. Three months to change her life.

The tour bus arrives at a junction in front of a one-storey building constructed of concrete blocks. A donkey stands tethered to a petrol pump with red paint faded by the sun. Above a window a Coca-Cola sign in looping Arabic script hangs precariously from a rusty hook. Someone’s nailed a hand-painted sign of waterfalls to a post, an arrow pointing towards mountains in the distance. The driver grinds the gears and steers the bus towards the mountains.

A half-hour later, the bus pulls into a dirt square surrounded by a jumble of buildings in various stages of construction. A group of men sits on the hill overlooking the square. The younger men wear designer jeans and hold cell phones close to their ears. The faces of the older men are deeply creased, like old leather shoes. Some suck on cigarette stubs. They wear dusty flannel trousers under brown hooded djellabas. Many of them have bright blue turbans wrapped around their heads. They’re like hungry eagles eyeing their prey.

One of the younger men separates from the group and jogs down the hill. He moves lightly like a deer, his feet finding an easy path down the rocky hillside. He wears a bright blue gown embroidered with yellow symbols over his jeans. The long tail of his blue turban flaps behind him as he lopes down the hill.

‘Sbah lkhir,’ he calls to the driver.

The driver laughs at something he says and offers him a cigarette from a crumpled Marlboro packet. The young man shakes his head and slaps the driver on the back. The driver shrugs and holds the Marlboro packet up to his lips then pulls out a cigarette with his teeth. He grabs a green plastic lighter from his dashboard, clicking under the end of the cigarette until it glows. Sucking in his cheeks, he blows out the smoke with an ‘Ahhh.’

The young man turns to face the passengers. He’s tall and slim and his blue gown floats around his body. His face is angular, his jaw strong, and his amber eyes are almond-shaped and deep-set. His lips are full and when he smiles a dimple shadows his right cheek.

‘Sbah lkhir. Good morning. Allô, bonjour, comment ça va?’ He flashes a white smile. ‘I am Omar. I am your tour guide, votre guide touristique.’ He thumps his chest with the flat of his hand and gestures around him. ‘You are welcome to my paradise and to the place of the most beautiful waterfalls in Morocco, the Cascades de Zitoune. In English, the Waterfalls of the Olive.’

He claps his hands together and flashes another white-toothed smile. ‘So, you are all happy? You are ready for the big adventure of your life?’

Addy waves at him.

‘Yes, allô?’

The blood rises in her cheeks as she feels the eyes of the other tourists on her.

‘I’m sorry. I’m not here for the tour. I just caught a lift on the tour bus because it was the easiest way here. I need to find the house I’m renting.’

‘I’m so, so sorry for that.’ His accent is heavy, the English syllables embellished with Arabic rolls of the tongue. ‘You’ll miss the best tour with the best tour guide in Morocco. But, anyway, what is the address? Is it Dar Fatima? The Hôtel de France? I can take you.’

‘No, it’s a house near the river. I can manage. I don’t want to delay your tour.’

Omar waggles his finger at her. ‘Mashi mushkil. I know the house. It’s the place of Mohammed Demsiri. Where’s your luggage? Your husband is coming soon?’

‘No. Just me. My bags are at the back. I don’t have much.’

‘No problem. I’ll make a good arrangement for you.’

‘I, but … I don’t want to be any trouble.’

Omar says something to the driver, who tosses his cigarette out of the window and starts the ignition. The door’s still open and Omar hangs half in and half out, his feet wedged against the opening. As the tour bus cuts across the square towards a small rusty bridge, he calls out to acquaintances in a guttural language. Addy sucks in her breath as the bridge’s loose boards clatter beneath the bus’s tyres.

The tour bus turns right down a narrow lane and stops in front of a squat mud house. A large inverted triangle is centred on the blue metal door and two tiny windows protected by black metal grilles have been cut into the orange pisé wall. Omar jumps out of the bus and bangs on the blue door. A woman’s voice calls out from behind the door.

‘Chkoun?’

‘Omar.’

The door opens. A young woman in pink flannelette pyjamas and a lime green hijab stands on the threshold. She wears purple Crocs and carries a wooden spoon dripping with batter. She has the same full lips and high cheekbones as Omar in her dark-skinned face. Omar gestures at the bus, his guttural words flying at her like bullets. The girl waves her spoon at Omar, flinging batter over his blue gown as she volleys back a shrill response.

Omar catches Addy’s eye. ‘One minute, one minute.’ He grabs the girl by the arm and they disappear behind the door.

A few minutes later he emerges and beckons to Addy.

‘Come.’

‘This isn’t the house on the Internet.’

‘Don’t worry. It’s the house of my family. We’ll put the luggage here and you can come on the tour. I’ll bring you to your house later.’

‘But …’

He presses his hand onto his chest. ‘I am Omar. Everybody knows me here. It’s no problem. Don’t worry.’

Philippa’s voice echoes in her head: Whatever you do, Addy, don’t trust those Moroccan men. They’re only after one thing. A British passport.

Omar shrugs. ‘Okay, so no problem. You don’t trust me, I can see it. It’s not a requirement for you to come to my house. We go to the waterfalls.’

‘No, it’s fine. I’m coming.’

‘About bloody time, too,’ a girl with a Geordie accent grumbles from the back of the bus. ‘We could’ve crossed the bloody Sahara by camel by now.’

Omar stands in a dirt-floored courtyard with the girl and two older women. A woman who looks about fifty-five stands ramrod straight and wears a red gypsy headscarf, an orange blouse buttoned to her chin, and a red-and-white striped apron over layers of skirts and flannelette pyjamas. Silver coins hang from her pierced ears and the inner lids of her amber eyes are ringed with kohl.

Beside her, an old woman in a flowered flannel housecoat and red bandana leans heavily on a knotty wooden stick. A thick silver ring marked with crosses and X’s slides around one of her gnarled fingers. Her left eye is closed and the right eye that peers out from her wrinkled face is a translucent blue. She has a blue arrow tattooed on her chin.

‘It’s my mum, my sister and my grandmother,’ Omar says, waving at the women.

Addy sets down her camera bag and her overnight bag. A clothesline has been strung across the yard and fresh washing hangs on the line dripping onto the dirt floor. A couple of scrawny chickens scratch in the red dirt. Addy extends her hand to his mother.

‘Bonjour.’

The woman takes hold of Addy’s hand in both of hers then smiles and nods. Her eyes sweep over Addy’s naked arms. She says something to Omar, who chuckles.

A small boy barges in through the door dragging Addy’s suitcase and tripod bag and deposits them next to her other luggage. Omar retrieves a coin from the pocket of his blue robe and flips it to the boy, who catches it, shouting ‘Shukran’ as he runs out of the door. The metal door bangs against its loose hinges.

The old woman waves her stick at the door and shuffles off through an archway, mumbling. Omar’s mother and sister pick up Addy’s luggage and follow the old woman into the next room.

‘Where are they going?’

‘Don’t worry. They put them in a safe place so the chickens and donkey don’t break them.’

‘Oh. Thank you.’

‘No problem. Mashi mushkil.’

‘Mashy mushkey.’

‘It’s a good accent. It’s Darija. Arabic of Morocco.’

‘It sounds different here from what I heard in Marrakech.’

‘Here we speak Tamazight mostly. It’s Amazigh language.’

‘Amazigh?’

‘Yes. We say Amazigh for one person and Imazighen for many people. Everybody else says Berber, but we don’t like it so well, even though we say it for tourists because it’s more easy. The Romans called us that because they say we were like barbarians. It’s because we fight them well. We are the first people of North Africa. We’re free people. It’s what Imazighen means. We’re not Arab in the mountains.’

‘Oh. I didn’t know that.’

‘So, I’m a good teacher, isn’t it? My sister speaks Darija and some French from her school, but my mum and grandmother speak Tamazight only.’

‘And your father?’

‘My father, he’s died.’

‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean …’

Omar shrugs. ‘Don’t mind. It’s life.’ Omar pinches the fabric of his blue gown between his fingers. ‘It’s the special blue colour of the Imazighen. It used to be that the Tuareg Berbers in the Sahara crushed indigo powder into white clothes to make them blue to be safe from the djinn. But when it was very hot the blue colour make their faces blue as well. People called them the blue men of the desert.’

Omar drapes the loose end of his blue turban across his face, covering his nose and mouth. ‘It’s a tagelmust. It’s for the desert, but the tourists love it so we wear it everywhere now. For us, it’s the man who covers his face, not the ladies.’ He folds his arms across his chest and spreads his feet apart. ‘I’m handsome, isn’t it?’

‘I’m sure you break the hearts of all the women tourists.’

Omar tugs at the cloth covering his face. ‘I never go with the tourist ladies. It’s many ladies in Zitoune who want to marry me, but I say no. My mum don’t like it. She want many grandchildren.’

‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to offend …’

Omar tucks the tail of the tagelmust into his turban. ‘Mashi mushkil.’

A black-and-white cat brushes against her legs and Addy reaches down to brush its tail.

‘What a pretty cat.’

Omar shifts on his feet. ‘It’s the cat of my grandmother. It’s very, very old.’

‘Really? It doesn’t look old.’

‘She had it a long time anyway. It always follows her. It’s very curious all the time.’

Omar clears his throat. ‘It must be that I know your name.’

She stands up quickly and thrusts out her hand. ‘Addy.’

A wet pant leg wraps around her wrist like a damp leaf. She tries to shake it loose but the clothesline collapses, throwing the damp laundry into heaps on the dusty ground. The cat shoots across the courtyard and out through a crack in a thick wooden door.

Addy stares at the dust turning to red mud on the clothes. She stoops to pick up the dirty laundry.

‘I’m so sorry. I’ve messed up your mother’s laundry.’

Omar lifts the wet bundle out of Addy’s hands. ‘No mind, Adi.’ The vowels of her name curl and roll off his tongue, the accent on the last syllable. Omar stacks the wet laundry on top of a low wooden table. ‘It’s a boy’s name in Morocco. You have short hair like a boy anyway.’

Addy runs her fingers over her cropped hair. The softness still surprises her. Hair like a baby’s. A side effect of the Red Devil.

Omar wipes his muddy hands on his gown. ‘So, Adi of England. Yalla. We go.’