Читать книгу Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly - Агата Кристи, Agatha Christie, Detection Club The - Страница 5

Introduction by Tom Adams

ОглавлениеMORE THAN half a century ago – 1962 to be precise – my impressively-named and enthusiastic agent, Virgil Pomfret, took me to meet the art director of Fontana Paperbacks, Patsy Cohen. On her desk was a copy of The Collector, John Fowles’ first published novel. It had been commissioned by Tony Colwell, art director at Jonathan Cape, and was my first serious attempt at trompe l’oeil painting for jacket art. It was a good time to be producing art for book covers. Good art was notably lacking in this field, particularly for paperbacks. In fact, the general standard was pretty dire, and the time was ripe for raising the bar. Up to then I had enjoyed doing serious paintings for hardback jackets, which included John Fowles’ The Magus, Patrick White’s Vivisector and David Storey’s Saville. Paperback covers were more often than not the poor second class products of publishers’ lists (with exceptions such as the original typographical Penguin covers), but virtually no serious attempt had been made to commission good art for paperbacks. However with the enthusiastic encouragement of Mark Collins, Virgil Pomfret and Patsy Cohen, I think we succeeded in doing just that.

From 1962 onwards, my relationship with Agatha Christie developed and prospered as I produced more than a hundred cover paintings for her books over twenty-five years. To begin with I simply enjoyed doing a good job. There were inevitably some failures and I know that I didn’t always please Agatha or her family. I am frequently asked if I met Agatha. I’m afraid the answer is no. Arrangements were made for various meetings; I did meet Rosalind Hicks, her daughter, Edmund Cork, her agent, and other members of her entourage, but Agatha’s legendary reticence and occasional illness prevented her from accepting invitations for us to meet. In retrospect I think it was just as well; it might have been embarrassing for both of us to discuss the likes and dislikes of various cover images. Nevertheless, for me it is a niggling regret. More recently, since my exhibition of Agatha Christie cover paintings at Torquay Museum in 2012, I have on several occasions met Mathew Prichard, a devoted and eloquent advocate of his grandmother’s achievements. Mathew and his wife Lucy have been a tower of strength and gratifyingly appreciative of my work. They helped and encouraged me in my recent endeavours on Agatha’s behalf, in particular while working on the cover painting for Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly, and they arranged with the National Trust to make Greenway House and garden available for my research. Once, after a delightful lunch with Mathew and Lucy at Ferry Cottage, and with my wife, the children’s writer Georgie Adams, we were taken on a memorable boat trip on the River Dart.

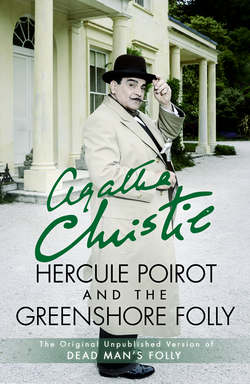

I was delighted when David Brawn, Publisher of Agatha Christie at HarperCollins, asked me to do this special cover painting for a so-far unpublished story. It is a shorter version of the excellent Dead Man’s Folly and a great excuse for me to revisit Greenway. Agatha’s second husband Max Mallowan described Greenway as ‘this little paradise’, and it was for Agatha ‘the loveliest place in the world’. And it is. The handsome, foursquare, no-nonsense Georgian house is in many ways an embodiment of its famous literary owner. But it is the garden that is the true paradise. In my painting I have tried, within the constrictions of being true to the story, to embody its extraordinary beauty and magic. It is without doubt one of the iconic places of the West Country – that West Country with its rain-soaked and occasionally sun-soaked landscape, haunted moors and secret bosky woodlands, fringed by sea and rocky shores.

Greenway has a flamboyant garden, almost tropical in places and bordered by the Dart, and is now owned by the National Trust. For Agatha it provided a safe retreat from an often intrusive outside world, a world she was fascinated by and acutely observed, but into which she had no wish to be integrated.

This great detective story writer, this skilled puzzle and plot maker, was the inspiration for my work on her books. My painting for this story is a tribute to her house and garden but, nevertheless, it had to fulfil its function as an illustration. I know that Agatha instinctively disliked visual depictions of actual incidents, scenes and human figures, and in particular insisted that Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple must not be shown on the covers. Though Collins tended to adhere to these rules, her American publishers demanded more literal imagery, as demonstrated by the US version of Dead Man’s Folly, reproduced on the endpapers of this book. I have largely obeyed this sensible injunction but it is right to break rules sometimes as I have for the cover of The Greenshore Folly, in which there is some pure illustration, for instance: the house, the boathouse, the ferry bell and Battery; the magnolia (one of Agatha’s favourite flowers), the face of Lady Stubbs, the fallen oak and folly; even a slightly fantasised portrait of Agatha herself in a cherished garden nook. And there is a suggestion of a convivial crowd on the front lawn. All this is woven into what I hope is a pictorial tribute to Greenway.

Readers may note that I thatched the boathouse, as described in the story. Today it has a slate roof, but Mathew Prichard remembers it was originally thatched. So I have unwittingly restored the building to its former glory!

I make no claims to be a great artist in the same league as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud or Graham Sutherland. Nevertheless I consider myself to be a good painter and illustrator and worthy I hope of a place somewhere in the middle of the pantheon of British 20th/21st-century art. Incidentally Graham Sutherland became a friend and mentor in the mid-fifties when I was a close neighbour in the Kentish village of Trottiscliffe. My visits to his White House studio and his to my Oast House studio were highlights of my early life as an artist. That I have been lucky enough to have survived into the 21st century and still working in my eighties is largely due to the care and loving support of my family and dear friends, not to mention great and understanding publishers and patrons, including Jonathan Cape and HarperCollins. John Fowles generously placed me in ‘one of the pleasantest traditions in English art, which goes back essentially to the great woodcut school of the 1860s; and descends through Rackham, Dulac, the Detmold brothers to our own day. Tom stands honourably in that long line …’ This is all very fine but it is the stimulation of great writers like John Fowles and Agatha Christie that inspired me in my career as an illustrator and cover artist. And I have the temerity to compare myself as an artist to Agatha as a crime novelist. Patient research and dedicated craftsmanship are key to our success. I have always thought that an infinite capacity to take pains was a somewhat inadequate definition of genius, but it is a good part of that elusive quality. Undeniably Christie had that quality, that magic ingredient. Whether or not I do is for others to decide.

Over the years I have had a growing conviction that Agatha Christie was without doubt pre-eminent as a writer of crime fiction. She was a weaver of spells, someone who leads us up and down the garden path, round and round in circles, only to deposit us in an unexpected place. Oh good heavens, we say. We didn’t see that coming! From the first words of advice she received from her friend, Eden Philpotts, Agatha learned that writing was a craft as well as an art and that there are methods and tricks for overcoming stylistic and technical obstacles.

Agatha’s work is a gift to the visual artist. Characters, locations, and objects provide a rich choice of subjects, but the lack of specific detail in her descriptions allows the illustrator to imagine and manipulate. As for imagination, Agatha had it in spades. According to Janet Morgan in Agatha Christie – A Biography, she was deeply affected by two books: J.W. Dunne’s Experiment With Time and The Mysterious Universe by Sir James Jeans, inspiring her to write to Max in 1930:

‘I understand very little of it but it fills me with nebulous ideas. How queer it would be if God were in the future – something we never created or imagined but who is not yet – supposing him to be not Cause but Effect … It’s fun to play with ideas – that God has made the world as it is and is pleased with it seems certainly not so. Originally man starved to death and froze to death (on top of coal in the ground) and every plague and pestilence caused by Man’s stupidity was put down to “God’s Will”. If life on this planet is an accident, quite unforeseen, and against all the principles of the solar system – how amazingly interesting – and when may it end? In some complete and marvellous Consciousness …’

Janet Morgan’s excellent biography discusses how Agatha was a prolific and ingenious fantasist. She ‘dreamt vividly, remembered and talked of her dreams, relished them – dreams of flying …’ I have the same propensity to fantasise and dream, especially dreams of flying, and I’ve always thought this is one of the many reasons I empathise so well with Agatha in her books.

However, Agatha was also a very down-to-earth person. Her own autobiography shows something of her humanity and wit:

‘I don’t like crowds, being jammed up against people, loud voices, noise, protracted talking, parties, and especially cocktail parties, cigarette smoke and smoking generally, any kind of drink except in cooking, marmalade, oysters, lukewarm food, grey skies, the feet of birds, or indeed the feel of a bird altogether. Final and fiercest dislike: the taste and smell of hot milk.

‘I like sunshine, apples, almost any kind of music, railway trains, numerical puzzles and anything to do with numbers, going to the sea, bathing and swimming, silence, sleeping, dreaming, eating, the smell of coffee, lilies of the valley, most dogs, and going to the theatre.

‘I could make much better lists, much grander-sounding, much more important, but there again it wouldn’t be me, and I suppose I must resign myself to being me.’

Agatha worked by herself: ‘The most blessed thing about being an author is that you do it in private and in your own time’. I profoundly echo these sentiments! My working conditions are a studio stacked with stuff, books everywhere and everything extremely untidy. I get the feeling that on the much smaller scale of a writer’s workspace Agatha was not that much more concerned with order and tidiness than I am. When asked on BBC’s radio programme, Close-Up, about her process of working, Agatha admitted: ‘The disappointing truth is that I haven’t much method’. And in John Curran’s comprehensively perceptive book, Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Making, he points out: ‘She thrived mentally on chaos, it stimulated her more than neat order; rigidity stifled her creative process.’ This was her method and it works for me too. Out of my chaos, sketches and multiple reference notes, my finished painting emerges.

Archaeology is something else Agatha and I have in common. She was married to archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan. My eldest son, Professor Jonathan Adams, is a marine archaeologist. He was Deputy Director of the excavation and raising of the Mary Rose and assembles and recreates a logical whole from an unlikely jumble of apparently unrelated bits and pieces – much as I do as an artist – and he is a fine painter. In our own ways we both share much in common with Agatha’s method of writing, and I think the processes and activities involved in archaeology are similar to the writing of detective stories: the assembly of pieces, finding facts, following clues, digging below the surface, and taking leaps of imagination …

As well as writing books, Agatha Christie was also a very accomplished playwright. My own passion for the theatre began with memories of my parents’ active life producing and acting in amateur dramatics. I was privileged to meet many of their theatrical friends such as Flora Robson and Sybil Thorndike, and I have many happy memories of being taken to theatres in London and Paris. My mother, Constance, was a pupil of Dame Carrie Tubbs at the Guildhall School of Music, though regrettably she gave up singing when she got married. Agatha trained as a singer, but she gave it up for writing.

With the painting of the new cover for Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly, my association with Agatha Christie as her cover artist now exceeds fifty years. I hope that I will have the opportunity to do more. My conviction about this remarkable author that has steadily grown over the many years of our association can be summed up no better than this quote from a News Chronicle reviewer which appears in John Curran’s Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Making: ‘Mrs Christie is the greatest genius at inventing detective plots that has ever lived or will ever live’. I couldn’t put it better myself.

Tom Adams

Cornwall

January 2014