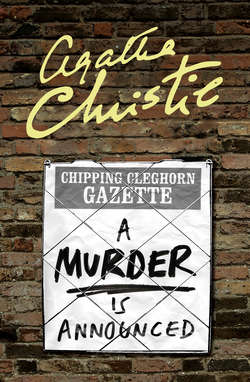

Читать книгу A Murder is Announced - Агата Кристи, Agatha Christie, Detection Club The - Страница 6

CHAPTER 1 A Murder is Announced

ОглавлениеBetween 7.30 and 8.30 every morning except Sundays, Johnnie Butt made the round of the village of Chipping Cleghorn on his bicycle, whistling vociferously through his teeth, and alighting at each house or cottage to shove through the letterbox such morning papers as had been ordered by the occupants of the house in question from Mr Totman, stationer, of the High Street. Thus, at Colonel and Mrs Easterbrook’s he delivered The Times and the Daily Graphic; at Mrs Swettenham’s he left The Times and the Daily Worker; at Miss Hinchcliffe and Miss Murgatroyd’s he left the Daily Telegraph and the News Chronicle; at Miss Blacklock’s he left the Telegraph, The Times and the Daily Mail.

At all these houses, and indeed at practically every house in Chipping Cleghorn, he delivered every Friday a copy of the North Benham News and Chipping Cleghorn Gazette, known locally simply as ‘the Gazette’.

Thus, on Friday mornings, after a hurried glance at the headlines in the daily paper

(International situation critical! U.N.O. meets today! Bloodhounds seek blonde typist’s killer! Three collieries idle. Twenty-three die of food poisoning in Seaside Hotel, etc.)

most of the inhabitants of Chipping Cleghorn eagerly opened the Gazette and plunged into the local news. After a cursory glance at Correspondence (in which the passionate hates and feuds of rural life found full play) nine out of ten subscribers then turned to the PERSONAL column. Here were grouped together higgledy-piggledy articles for Sale or Wanted, frenzied appeals for Domestic Help, innumerable insertions regarding dogs, announcements concerning poultry and garden equipment; and various other items of an interesting nature to those living in the small community of Chipping Cleghorn.

This particular Friday, October 29th—was no exception to the rule—

Mrs Swettenham, pushing back the pretty little grey curls from her forehead, opened The Times, looked with a lacklustre eye at the left-hand centre page, decided that, as usual, if there was any exciting news The Times had succeeded in camouflaging it in an impeccable manner; took a look at the Births, Marriages and Deaths, particularly the latter; then, her duty done, she put aside The Times and eagerly seized the Chipping Cleghorn Gazette.

When her son Edmund entered the room a moment later, she was already deep in the Personal Column.

‘Good morning, dear,’ said Mrs Swettenham. ‘The Smedleys are selling their Daimler. 1935—that’s rather a long time ago, isn’t it?’

Her son grunted, poured himself out a cup of coffee, helped himself to a couple of kippers, sat down at the table and opened the Daily Worker which he propped up against the toast rack.

‘Bull mastiff puppies,’ read out Mrs Swettenham. ‘I really don’t know how people manage to feed big dogs nowadays—I really don’t … H’m, Selina Lawrence is advertising for a cook again. I could tell her it’s just a waste of time advertising in these days. She hasn’t put her address, only a box number—that’s quite fatal—I could have told her so—servants simply insist on knowing where they are going. They like a good address … False teeth—I can’t think why false teeth are so popular. Best prices paid … Beautiful bulbs. Our special selection. They sound rather cheap … Here’s a girl wants an “Interesting post—Would travel.” I dare say! Who wouldn’t?… Dachshunds … I’ve never really cared for dachshunds myself—I don’t mean because they’re German, because we’ve got over all that—I just don’t care for them, that’s all.—Yes, Mrs Finch?’

The door had opened to admit the head and torso of a grim-looking female in an aged velvet beret.

‘Good morning, Mum,’ said Mrs Finch. ‘Can I clear?’

‘Not yet. We haven’t finished,’ said Mrs Swettenham. ‘Not quite finished,’ she added ingratiatingly.

Casting a look at Edmund and his paper, Mrs Finch sniffed, and withdrew.

‘I’ve only just begun,’ said Edmund, just as his mother remarked:

‘I do wish you wouldn’t read that horrid paper, Edmund. Mrs Finch doesn’t like it at all.’

‘I don’t see what my political views have to do with Mrs Finch.’

‘And it isn’t,’ pursued Mrs Swettenham, ‘as though you were a worker. You don’t do any work at all.’

‘That’s not in the least true,’ said Edmund indignantly. ‘I’m writing a book.’

‘I meant real work,’ said Mrs Swettenham. ‘And Mrs Finch does matter. If she takes a dislike to us and won’t come, who else could we get?’

‘Advertise in the Gazette,’ said Edmund, grinning.

‘I’ve just told you that’s no use. Oh dear me, nowadays unless one has an old Nannie in the family, who will go into the kitchen and do everything, one is simply sunk.’

‘Well, why haven’t we an old Nannie? How remiss of you not to have provided me with one. What were you thinking about?’

‘You had an ayah, dear.’

‘No foresight,’ murmured Edmund.

Mrs Swettenham was once more deep in the Personal Column.

‘Second hand Motor Mower for sale. Now I wonder … Goodness, what a price!… More dachshunds … “Do write or communicate desperate Woggles.” What silly nicknames people have … Cocker Spaniels … Do you remember darling Susie, Edmund? She really was human. Understood every word you said to her … Sheraton sideboard for sale. Genuine family antique. Mrs Lucas, Dayas Hall … What a liar that woman is! Sheraton indeed …!’

Mrs Swettenham sniffed and then continued her reading:

‘All a mistake, darling. Undying love. Friday as usual.—J … I suppose they’ve had a lovers’ quarrel—or do you think it’s a code for burglars?… More dachshunds! Really, I do think people have gone a little crazy about breeding dachshunds. I mean, there are other dogs. Your Uncle Simon used to breed Manchester Terriers. Such graceful little things. I do like dogs with legs … Lady going abroad will sell her navy two piece suiting … no measurements or price given … A marriage is announced—no, a murder. What? Well, I never! Edmund, Edmund, listen to this …

‘A murder is announced and will take place on Friday, October 29th, at Little Paddocks at 6.30 p.m. Friends please accept this, the only intimation.

‘What an extraordinary thing! Edmund!’

‘What’s that?’ Edmund looked up from his newspaper.

‘Friday, October 29th … Why, that’s today.’

‘Let me see.’ Her son took the paper from her.

‘But what does it mean?’ Mrs Swettenham asked with lively curiosity.

Edmund Swettenham rubbed his nose doubtfully.

‘Some sort of party, I suppose. The Murder Game—that kind of thing.’

‘Oh,’ said Mrs Swettenham doubtfully. ‘It seems a very odd way of doing it. Just sticking it in the advertisements like that. Not at all like Letitia Blacklock who always seems to me such a sensible woman.’

‘Probably got up by the bright young things she has in the house.’

‘It’s very short notice. Today. Do you think we’re just supposed to go?’

‘It says “Friends, please accept this, the only intimation,”’ her son pointed out.

‘Well, I think these new-fangled ways of giving invitations are very tiresome,’ said Mrs Swettenham decidedly.

‘All right, Mother, you needn’t go.’

‘No,’ agreed Mrs Swettenham.

There was a pause.

‘Do you really want that last piece of toast, Edmund?’

‘I should have thought my being properly nourished mattered more than letting that old hag clear the table.’

‘Sh, dear, she’ll hear you … Edmund, what happens at a Murder Game?’

‘I don’t know, exactly … They pin pieces of paper upon you, or something … No, I think you draw them out of a hat. And somebody’s the victim and somebody else is a detective—and then they turn the lights out and somebody taps you on the shoulder and then you scream and lie down and sham dead.’

‘It sounds quite exciting.’

‘Probably a beastly bore. I’m not going.’

‘Nonsense, Edmund,’ said Mrs Swettenham resolutely. ‘I’m going and you’re coming with me. That’s settled!’

‘Archie,’ said Mrs Easterbrook to her husband, ‘listen to this.’

Colonel Easterbrook paid no attention, because he was already snorting with impatience over an article in The Times.

‘Trouble with these fellows is,’ he said, ‘that none of them knows the first thing about India! Not the first thing!’

‘I know, dear, I know.’

‘If they did, they wouldn’t write such piffle.’

‘Yes, I know. Archie, do listen.

‘A murder is announced and will take place on Friday, October 29th (that’s today), at Little Paddocks at 6.30 p.m. Friends please accept this, the only intimation.’

She paused triumphantly. Colonel Easterbrook looked at her indulgently but without much interest.

‘Murder Game,’ he said.

‘Oh.’

‘That’s all it is. Mind you,’ he unbent a little, ‘it can be very good fun if it’s well done. But it needs good organizing by someone who knows the ropes. You draw lots. One person’s the murderer, nobody knows who. Lights out. Murderer chooses his victim. The victim has to count twenty before he screams. Then the person who’s chosen to be the detective takes charge. Questions everybody. Where they were, what they were doing, tries to trip the real fellow up. Yes, it’s a good game—if the detective—er—knows something about police work.’

‘Like you, Archie. You had all those interesting cases to try in your district.’

Colonel Easterbrook smiled indulgently and gave his moustache a complacent twirl.

‘Yes, Laura,’ he said. ‘I dare say I could give them a hint or two.’

And he straightened his shoulders.

‘Miss Blacklock ought to have asked you to help her in getting the thing up.’

The Colonel snorted.

‘Oh, well, she’s got that young cub staying with her. Expect this is his idea. Nephew or something. Funny idea, though, sticking it in the paper.’

‘It was in the Personal Column. We might never have seen it. I suppose it is an invitation, Archie?’

‘Funny kind of invitation. I can tell you one thing. They can count me out.’

‘Oh, Archie,’ Mrs Easterbrook’s voice rose in a shrill wail.

‘Short notice. For all they know I might be busy.’

‘But you’re not, are you, darling?’ Mrs Easterbrook lowered her voice persuasively. ‘And I do think, Archie, that you really ought to go—just to help poor Miss Blacklock out. I’m sure she’s counting on you to make the thing a success. I mean, you know so much about police work and procedure. The whole thing will fall flat if you don’t go and help to make it a success. After all, one must be neighbourly.’

Mrs Easterbrook put her synthetic blonde head on one side and opened her blue eyes very wide.

‘Of course, if you put it like that, Laura …’ Colonel Easterbrook twirled his grey moustache again, importantly, and looked with indulgence on his fluffy little wife. Mrs Easterbrook was at least thirty years younger than her husband.

‘If you put it like that, Laura,’ he said.

‘I really do think it’s your duty, Archie,’ said Mrs Easterbrook solemnly.

The Chipping Cleghorn Gazette had also been delivered at Boulders, the picturesque three cottages knocked into one inhabited by Miss Hinchcliffe and Miss Murgatroyd.

‘Hinch?’

‘What is it, Murgatroyd?’

‘Where are you?’

‘Henhouse.’

‘Oh.’

Padding gingerly through the long wet grass, Miss Amy Murgatroyd approached her friend. The latter, attired in corduroy slacks and battledress tunic, was conscientiously stirring in handfuls of balancer meal to a repellently steaming basin full of cooked potato peelings and cabbage stumps.

She turned her head with its short man-like crop and weather-beaten countenance toward her friend.

Miss Murgatroyd, who was fat and amiable, wore a checked tweed skirt and a shapeless pullover of brilliant royal blue. Her curly bird’s nest of grey hair was in a good deal of disorder and she was slightly out of breath.

‘In the Gazette,’ she panted. ‘Just listen—what can it mean?

‘A murder is announced … and will take place on Friday, October 29th, at Little Paddocks at 6.30 p.m. Friends please accept this, the only intimation.’

She paused, breathless, as she finished reading, and awaited some authoritative pronouncement.

‘Daft,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe.

‘Yes, but what do you think it means?’

‘Means a drink, anyway,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe.

‘You think it’s a sort of invitation?’

‘We’ll find out what it means when we get there,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe. ‘Bad sherry, I expect. You’d better get off the grass, Murgatroyd. You’ve got your bedroom slippers on still. They’re soaked.’

‘Oh, dear.’ Miss Murgatroyd looked down ruefully at her feet. ‘How many eggs today?’

‘Seven. That damned hen’s still broody. I must get her into the coop.’

‘It’s a funny way of putting it, don’t you think?’ Amy Murgatroyd asked, reverting to the notice in the Gazette. Her voice was slightly wistful.

But her friend was made of sterner and more single-minded stuff. She was intent on dealing with recalcitrant poultry and no announcement in a paper, however enigmatic, could deflect her.

She squelched heavily through the mud and pounced upon a speckled hen. There was a loud and indignant squawking.

‘Give me ducks every time,’ said Miss Hinchcliffe. ‘Far less trouble …’

‘Oo, scrumptious!’ said Mrs Harmon across the breakfast table to her husband, the Rev. Julian Harmon, ‘there’s going to be a murder at Miss Blacklock’s.’

‘A murder?’ said her husband, slightly surprised. ‘When?’

‘This afternoon … at least, this evening. 6.30. Oh, bad luck, darling, you’ve got your preparations for confirmation then. It is a shame. And you do so love murders!’

‘I don’t really know what you’re talking about, Bunch.’

Mrs Harmon, the roundness of whose form and face had early led to the soubriquet of ‘Bunch’ being substituted for her baptismal name of Diana, handed the Gazette across the table.

‘There. All among the second-hand pianos, and the old teeth.’

‘What a very extraordinary announcement.’

‘Isn’t it?’ said Bunch happily. ‘You wouldn’t think that Miss Blacklock cared about murders and games and things, would you? I suppose it’s the young Simmonses put her up to it—though I should have thought Julia Simmons would find murders rather crude. Still, there it is, and I do think, darling, it’s a shame you can’t be there. Anyway, I’ll go and tell you all about it, though it’s rather wasted on me, because I don’t really like games that happen in the dark. They frighten me, and I do hope I shan’t have to be the one who’s murdered. If someone suddenly puts a hand on my shoulder and whispers, “You’re dead,” I know my heart will give such a big bump that perhaps it really might kill me! Do you think that’s likely?’

‘No, Bunch. I think you’re going to live to be an old, old woman—with me.’

‘And die on the same day and be buried in the same grave. That would be lovely.’

Bunch beamed from ear to ear at this agreeable prospect.

‘You seem very happy, Bunch?’ said her husband, smiling.

‘Who’d not be happy if they were me?’ demanded Bunch, rather confusedly. ‘With you and Susan and Edward, and all of you fond of me and not caring if I’m stupid … And the sun shining! And this lovely big house to live in!’

The Rev. Julian Harmon looked round the big bare dining-room and assented doubtfully.

‘Some people would think it was the last straw to have to live in this great rambling draughty place.’

‘Well, I like big rooms. All the nice smells from outside can get in and stay there. And you can be untidy and leave things about and they don’t clutter you.’

‘No labour-saving devices or central heating? It means a lot of work for you, Bunch.’

‘Oh, Julian, it doesn’t. I get up at half-past six and light the boiler and rush around like a steam engine, and by eight it’s all done. And I keep it nice, don’t I? With beeswax and polish and big jars of Autumn leaves. It’s not really harder to keep a big house clean than a small one. You go round with mops and things much quicker, because your behind isn’t always bumping into things like it is in a small room. And I like sleeping in a big cold room—it’s so cosy to snuggle down with just the tip of your nose telling you what it’s like up above. And whatever size of house you live in, you peel the same amount of potatoes and wash up the same amount of plates and all that. Think how nice it is for Edward and Susan to have a big empty room to play in where they can have railways and dolls’ tea-parties all over the floor and never have to put them away? And then it’s nice to have extra bits of the house that you can let people have to live in. Jimmy Symes and Johnnie Finch—they’d have had to live with their in-laws otherwise. And you know, Julian, it isn’t nice living with your in-laws. You’re devoted to Mother, but you wouldn’t really have liked to start our married life living with her and Father. And I shouldn’t have liked it, either. I’d have gone on feeling like a little girl.’

Julian smiled at her.

‘You’re rather like a little girl still, Bunch.’

Julian Harmon himself had clearly been a model designed by Nature for the age of sixty. He was still about twenty-five years short of achieving Nature’s purpose.

‘I know I’m stupid—’

‘You’re not stupid, Bunch. You’re very clever.’

‘No, I’m not. I’m not a bit intellectual. Though I do try … And I really love it when you talk to me about books and history and things. I think perhaps it wasn’t an awfully good idea to read aloud Gibbon to me in the evenings, because if it’s been a cold wind out, and it’s nice and hot by the fire, there’s something about Gibbon that does, rather, make you go to sleep.’

Julian laughed.

‘But I do love listening to you, Julian. Tell me the story again about the old vicar who preached about Ahasuerus.’

‘You know that by heart, Bunch.’

‘Just tell it me again. Please.’

Her husband complied.

‘It was old Scrymgour. Somebody looked into his church one day. He was leaning out of the pulpit and preaching fervently to a couple of old charwomen. He was shaking his finger at them and saying, “Aha! I know what you are thinking. You think that the Great Ahasuerus of the First Lesson was Artaxerxes the Second. But he wasn’t!” And then with enormous triumph, “He was Artaxerxes the Third.”’

It had never struck Julian Hermon as a particularly funny story himself, but it never failed to amuse Bunch.

Her clear laugh floated out.

‘The old pet!’ she exclaimed. ‘I think you’ll be exactly like that some day, Julian.’

Julian looked rather uneasy.

‘I know,’ he said with humility. ‘I do feel very strongly that I can’t always get the proper simple approach.’

‘I shouldn’t worry,’ said Bunch, rising and beginning to pile the breakfast plates on a tray. ‘Mrs Butt told me yesterday that Butt, who never went to church and used to be practically the local atheist, comes every Sunday now on purpose to hear you preach.’

She went on, with a very fair imitation of Mrs Butt’s super-refined voice:

‘“And Butt was saying only the other day, Madam, to Mr Timkins from Little Worsdale, that we’d got real culture here in Chipping Cleghorn. Not like Mr Goss, at Little Worsdale, who talks to the congregation as though they were children who hadn’t had any education. Real culture, Butt said, that’s what we’ve got. Our Vicar’s a highly educated gentleman—Oxford, not Milchester, and he gives us the full benefit of his education. All about the Romans and the Greeks he knows, and the Babylonians and the Assyrians, too. And even the Vicarage cat, Butt says, is called after an Assyrian king!” So there’s glory for you,’ finished Bunch triumphantly. ‘Goodness, I must get on with things or I shall never get done. Come along, Tiglath Pileser, you shall have the herring bones.’

Opening the door and holding it dexterously ajar with her foot, she shot through with the loaded tray, singing in a loud and not particularly tuneful voice, her own version of a sporting song.

‘It’s a fine murdering day, (sang Bunch)

And as balmy as May

And the sleuths from the village are gone.’

A rattle of crockery being dumped in the sink drowned the next lines, but as the Rev. Julian Harmon left the house, he heard the final triumphant assertion:

‘And we’ll all go a’murdering today!’