Читать книгу Magnolia - Agnita Tennant - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

A Chronicle of April

1 April. When I met Mr Kwŏn at the tea-room ‘Rose’ we felt quite natural as if we had known each other for a long time. He made me sit beside him and ordered the coffee without asking me whether I wanted it or not. He had by him a red-covered book which turned out to be Grace Metalious’ Peyton Place. When he saw me eying it he said, ‘It was sent to me by a close friend from the time I was in America. Would you like to borrow it?’ I was delighted. Besides, I now knew that he had been to America. I was dying to ask him which state, and for how long, but I refrained. I might have appeared vulgar to show too much curiosity in someone else’s private life. But I am sure his experience will be helpful when my time comes. Probably his polished manners and the refinement in his clothing are thanks to his American experience. He praised me twice today. I know it is a weakness but when he praises me I get excited and silly.

‘You look very nice in that dress. It reminds me of a fashion model I knew once in the States.’

‘Goodness!’ I thought as I blushed. I was wearing my marine blue dress with a black satin belt tied in a bow at the back. I had a matching pair of high heeled shoes. As we came down the stairs I caught my reflection in the long mirror on the landing. With a black handbag slung over my shoulder and red-covered book tucked under my arm, I did look nice. From a few steps behind, he said again, ‘You do look smart, Sukey.’

I turned to face him, and looking up said with mock severity, ‘You shouldn’t make complimentary remarks to a lady’s face.’

‘Oh, I am sorry. I do apologize.’ He bowed from the waist. His quick and witty reaction made me laugh and he delightedly chuckled in his turn. We went to a Western restaurant. He asked me whether I liked dancing.

‘Like it?’ I said, ‘I can’t take the first step,’ as if I was proud of myself.

I thought he might say ‘That is not like you, Sukey, modern woman as you are.’ In which case I would have said, ‘It is not as if I object to dancing itself. I would love it. It’s just that I am waiting until I have a boyfriend with whom I can learn it properly.’ But there was no need. He rather praised me as he nodded his head and said, ‘I am pleased to hear that. It is just like you, Sukey.’

‘I expect you are good at it?’

‘No, no. I am like you. I have had many chances to learn but somehow missed them all. I was thinking you might be able to teach me.’

Is this not evidence of his innocence and shy personality? I felt as if I could relax my guard a bit. After dinner we went to a cinema to see a Korean film entitled ‘Money’. It was ten past eleven when we came out. He called a taxi, put me in the back seat, sat himself beside the driver and told him to go to Tonamdong, and then turning to me he said, ‘That’s where you live, isn’t it?’

I closed my eyes as I leaned my head back on the seat. The love scenes from the film came floating back. I wondered why he did not sit in the back next to me. Some men would have done. In a way I was glad it turned out that way. Only by keeping a respectable distance until the right time comes can we have the right kind of relationship. I would hate myself if I were to fall into a blind passion. When the taxi had passed the Samsŏn Bridge, I had to rouse myself from my reverie, to give the driver directions to our house. Kwŏn said that the new term starts in the middle of April, and he ought to be at his new post in Pusan by the tenth, at the latest. The thought of seeing him off at the railway station for it is a certainty now that I shall be there, made me emotional. I want to make the most of the remaining days and enjoy his company.

‘You must be tired,’ he said as he helped me out of the car and lightly patted my cheeks with his fingers.

‘Good night and thank you for a lovely evening.’

‘It’s my pleasure. Good night,’ he said and waved as he got into the car.

2 April. The first thing I meant to do when I got to work was to ring him. But when I entered the office the telephone was already ringing. It was him. I could not hide the delight from my voice.

‘Oh, is that you? Did you sleep well? How is it that you always answer the phone? Is it near you?’

‘Yes, it’s just on my desk.’

‘So I can ring you often, can I?’

‘Even if it wasn’t, you can ring me as often as you like.’

‘Didn’t you get a scolding from your sister for being late last night?’

‘Scolding? Why, I’m not a child, am I?’

He chuckled. I could see his face. I love him when he does that.

‘I’ve only just woken up. I am ringing from my bed. I have the phone just above my pillow. Are you busy?’

‘No, I am not. ‘I wanted to hold onto the phone. ‘What are you going to do today?’

‘I have to go into college, of course.’

‘Even on holidays?’

‘Yes. I’ve got a lot to tidy up in my office.’ Then he said, ‘It’s my mother just peeping round the door to see why I am lying in. I will ring you later. Bye for now.’

Before my eyes floated his room; a large ondol floored room, maybe a combined bedroom and study. Apart from the sliding doors that face the inner quarters across the wooden floored hall, the three walls will be lined with books from floor to ceiling. A desk with an adjustable lamp stand and a small bed-side table with a telephone and a night light on it. A loving mother frequently popping in and out to make sure he’s all right...

After work I met him again at the tea-room ‘Rose’. I’ve learned some more about him and his family. There has been a shortage of sons in his family and the family line had been maintained by only sons for the past six generations, and now he’s the heir of the seventh. He has both parents and a younger sister doing English literature at Ewha Women’s University. He told me about her at length. Apparently she’s a tomboy and spoilt rotten.

‘She tells me, ‘he said, ‘she and her friends have started some kind of a club and appointed me as their adviser, can you believe it? It’s their monthly meeting tonight, and I am expected to be there at seven-thirty. She kept popping in and out of my room even before I was fully awake to make me promise to be there.’ He went on with a smack of his tongue. ‘I shouted back and told her I didn’t want to have anything to do with such a cheeky bunch of girls. Why they didn’t even ask my opinion beforehand, and besides, I have a date tonight.’ Then he produced a crumpled piece of paper. ‘This is what she left on my pillow before she went out.’ In careless scrawl it read, ‘It’s all up to you, dear brother, whether you come or not, but really I don’t believe that you’ll let me down. The meeting place is “Liberty Salon”, in case you’ve forgotten, at 7.30 p.m. Your darling sis. Mirim.’

I smiled to myself. It reminded me of my ways with my own sister. These spoilt younger sisters! Then I thought if I were to develop a relationship with him, his sister would be an important person. Either I get on well with her and she will be my ally or she will set herself against me and play the devil’s advocate. Don’t I know the importance of a sister-in-law to one’s married life in this country!

‘Of course, you must go,’ I said. ‘I am unconditionally on her side.’

So he conceded to the two women and went to the meeting. Before we parted he invited me into a florist’s we were passing by and asked me to choose some flowers for myself. The small shop was filled with things like lilies, camellia, carnations, azalea and forsythia, but I did not fancy fully blown ones. It was sad to think that they would wither in a few days. I rather fancied the idea of watching over some buds growing into lovely leaves and flowers. I picked up a lump of roots with small, pointed tips – lilies of the valley. When I came home I put them in the flowerpot just outside the window. I shall water them everyday and have the pleasure of seeing them grow day by day.

3 April. He phoned during the morning. He has to go to a party tonight to welcome a friend who has just returned from America.

‘Would you care to come with me?’ he said. I briefly thought about it. It did not seem to be right to appear in public with a man I hardly know.

‘It’s just like you. I thought you might say that. I won’t insist against your wish.’ Then he said, ‘What about the fifth or the sixth? The fifth is a public holiday, isn’t it? Have you any plans?’

I looked up at the calendar on the wall. The fifth is Arbor Day, followed by Sunday.

‘If I can have the car on the fifth, I thought, it would be nice to drive out to the suburbs. Besides, my sister wants to meet you, she really does. Do you mind if she comes along?’ I thought to myself: what a lovely idea. I think I’ll get on famously well with her as she’s supposed to be a tomboy like myself. I already feel friendly towards her. I said, ‘I shall be delighted if she can come.’

‘Even if I don’t speak to you tomorrow, I’ll expect to see you at the usual place then, at 10 a.m. Is that OK? Make sure you have some idea of where you’d like to go.’ I smiled to myself at his tone of voice, which sounded like an intimate command.

‘I’d rather leave the programme of the day in your hands,’ I said and heard him chuckle.

5 April. I packed lunch for three with great care and went to ‘Rose’. He was alone.

‘Where’s your sister?’ I had put on clothes and shoes with her in mind. I had hoped to secure some sign of approval from her.

‘I am ashamed to say that she’s made herself unavailable. Apparently mother scolded her severely about something yesterday. She just walked out and did not come home last night. She’s terrible, she’s spoilt and so wilful causing us serious headaches sometimes.’ He clicked his tongue disconsolately and said, ‘I couldn’t call off our plan simply because of her, could I?’ He was right, I suppose, for there are only a couple more days before he goes to Pusan, but I could not hide my disappointment.

‘How sad. I really wanted to meet her more than you. Don’t you have to do something to bring her home?’

‘No, it’s nothing to worry about. We’re quite used to her ways, refusing to eat or leaving the house until she gets what she wants. Sounds awful, doesn’t she? But when she is nice, she’s the sweetest thing in the world. Would you like to see her picture?’ He produced a snapshot from his wallet. A young lady in tight-legged trousers of three quarter length with a check-patterned blouse, and a wide-brimmed straw hat was leaning on a walking stick as she brightly smiled by the wheel of a water-mill. An attractive face with large eyes and straight, high nose resembled that of her brother. I handed it back. ‘She’s lovely. She takes after you, doesn’t she?’ He just smiled.

‘Now, where would you like to go?’ He said briskly as he looked at his wrist-watch. It was past half past ten.

‘They brought in some plants at home yesterday. I picked up a couple for you and me to plant somewhere.’ What a romantic idea!

‘What are they?’

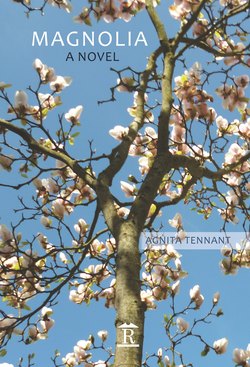

‘Magnolia.’

‘Magnolia! Wonderful!’ Filled with childlike delight I clapped my hands. ‘To plant magnolia, it would have to be some hills, do you think?’ Then I remembered Samgak Mountain. I knew it only through Kim Naesŏng’s novel The Lovers. The last scene is set on this mountain and it has left a deep impression on me. Its protagonist Kang Chiun and the heroine, Yi Yŏngsim, walk up the steep paths of this mountain, deep in untrodden snow. Their bodies and souls sealed in one accord, unconscious of the time or place or what lies ahead them, and rolling over in the snow, picking themselves up and propping up each other, they plod on towards the summit, leaving a trail of endless foot marks. I fancied seeing this mountain. As I walk up the valley towards the highest peak today, I thought, my own soul may be sealed in one aspiration – love.

‘Samgak Mountain – I’ve never been there but I’ve always wanted to go.’ Thus our destination was settled.

We got into a covered jeep with a driver waiting inside. There were two saplings in the back about a metre high, like two switches of equal length and thickness.

‘How did you find a pair so alike?’ I was impressed.

Once out of the city and past the Capitol Building and Hyojadong, the surface of the unpaved road was rough and it was full of sharp bends. Sitting on the back seat with the lunch box on my lap, I was thrown up and down each time the car bounced. I also had to mind my handbag that kept falling off the seat, and the saplings bouncing over from one side to the other. The driver noticing my plight in his mirror said, ‘May I suggest, sir, you go to the back and give the lady a hand. She’s got too much to cope with.’

‘I am sorry, it never occurred to me.’ He stopped the car, came over to the back seat, and took the lunch box and the plants off my hands. The driver turned round and smiled as if he was pleased with what he had done. Sitting so close to him I felt nervous. I tried hard to hold myself upright but as the road was getting rougher we were constantly thrown against each other. When it was a smooth going I could hear him breathing. I could not face his eyes so I kept mine fixed on the landscape outside, hoping he did not hear my heart beating fast. What will I do once we are in the woods with not a soul around? He seemed to be calm. Why can’t I be like that? He would laugh at me if he knew what I am like. I took a deep breath to compose myself.

In no time we were at the foot of the mountain where the car could go no further. He gave the driver some money as he said, ‘Thank you and goodbye.’ It seemed to be an excessive tip for a private driver but I could not dwell on such matters.

‘Have a good time, sir, and the lady too.’ He gave us a meaningful wink and turned away. Just the two of us, and not a soul around. We entered a pine wood following a narrow path. It was a beautiful day. Birds darted about chirruping as if welcoming some distinguished visitors. Yes, we are rather special people, I thought. We shall behave as fit for such people.

As the path grew wild and dangerous I fully recovered my calmness. I was happy now that I could behave naturally with him.

‘Are you sure you can make it to the top?’

‘Of course, I can.’

‘The one who gives up first will be the loser.’

‘And the loser will obey the winner.’ We heartily laughted.

We walked on up a steep rocky path, passing in and out several pine woods until we came to a little stream. We had a rest here, eating some chocolates and sweets I had brought in my bag, and started climbing again. The higher we went the more breathtaking the view became. Range after range of hills all round you, dells and woods below and crystal streams weaving through the ravines, and a torrent nearby, all in one view. I slightly shivered with awe.

By now, we were both panting and drenched in sweat. The trouble was that we were not properly dressed for climbing. Each time we had to clamber over a rock, he turned and put out his hand to help me but each time I declined. I wanted to show him my independence.

When we reached a spot from which we could see the summit just above our heads, we found a Buddhist temple and a small homestead.

‘Should we plant the trees here first,’ he said, ‘have some lunch and then go up the top?’

‘I was just going to suggest that. To make sure they come to no harm, it would be nice to plant them near the temple compound, and ask the people here to keep an eye on them.’

He went up to the main Hall and asked for the abbot. A man of about fifty came out, joined his palms as he bowed from the waist and said, ‘Welcome to our temple. What can we do for you?’ We stood side by side and bowed in greeting.

‘As it is Arbor Day today, we’ve brought a couple of saplings hoping to plant them somewhere here. We came to ask you if you would be able to keep an eye on them.’ He said it so smartly, so politely yet with such dignity I was proud of him.

‘Ah, is that so. That is a good idea,’ said the abbot. ‘Have you chosen the site?’

‘No, not yet. We’d appreciate it if you could help us. It would be nice if it was in front of the Main Hall.’

‘What are they?’

‘Magnolias.’

‘Ah, in that case, it’s an excellent idea to put them there,’ he pointed the rectangular flower-bed in front of the Main Hall. How splendid! I was congratulating myself on our luck. Just imagine, two splendid magnolias growing in front of the Main Hall of a temple. We will often come together to see how they are doing. Two monks came out from the inner quarters and started digging at either end of the flower-bed. When the holes were ready we took one each and planted them helped by the young men. After covering the roots and filling in the hole I smoothed the soil, treading on it to make it firm. I gave the plant a final jerk and watered it generously. I think it will grow into a splendid tree and produce magnificent flowers.

‘It is in commemoration of a special occasion. I would be obliged if you would take great care of them,’ he said. The term ‘commemoration of a special occasion’ roused a strange excitement in me.

‘Of course, I will,’ said the abbot. He looked pleased too. We were now being treated as honoured guests. We were shown into a room attached to the kitchen where we could eat the food we had brought. From outside it seemed a low-lying shack but it was spacious inside, cool and clean. There were two sets of sliding doors, one leading to the kitchen from which we had entered the room, and another looking out onto a small courtyard. We opened the latter, and across the courtyard, a splended scene came in view. Ridge lines of lower hills dense with trees stretched out as far as to the distant housing estate of Chŏngnŭng, the houses like a group of playing cards shimmering in a mirage. The doors to the kitchen slid open and a woman politely pushed in a small table with some side dishes of vegetables, two spoons and two sets of chopsticks, and two bowls of cold water. As a token of thanks, I handed her the spare lunch box. When she withdrew, I sat opposite him across the table. We smiled at each other. I was happy that all had gone well so far.

‘This is not very good but I prepared it with care, so I hope you enjoy it, ‘ I said as I handed him his lunch – rice tightly rolled in dry sheets of laver, with savoury centres of beef, eggs, dressed spinach and pickled turnip, then sliced into mouth-size pieces.

‘It’s delicious. I didn’t know you could cook so well.’ He finished his quickly and had some more of mine. Now that my stomach was full, I was overcome by drowsiness. My legs ached and every joint in my body seemed to be melting like candle wax. I longed for a nap.

‘I shall be very ill tomorrow. It’s my first climbing you see.’

‘I must say I was impressed. The dogged way you followed me was wonderful.’

‘I didn’t follow you. You just walked a couple of paces in front of me, that’s all.’

He gave his charming chuckle again. ‘You and your pride. I know your type. You can’t bear to be second or defeated, can you?’ I smiled and shrugged my shoulders. He guessed right. I am like that. Being second rate or defeated has rarely been part of my experience so far.

By now I could not keep my eyes open. As I leaned back against the wall they just drooped shut. When I forced my eyes open I saw, a couple of feet away, his burning eyes looking into mine. His face was tense as if he was going to have a fit.

‘When you are alone with a man in a room, make sure the door is left open. You can’t go too wrong if you think he is a hungry wolf. A tired face of a woman arouses a particular temptation in a man, so ideally you should meet him in the day time rather than in the evening.’ These were the words of the domestic science teacher at high school as she gave the last, special lessons to the school leavers. How Miae and I hated her guts. But at this moment her voice rang in my ears sweetly. I sat up straight and smoothed my hair and clothes. He must have sensed my alarm.

‘You must be very tired. Look, I’ll go out for a stroll and leave you to yourself so that you can relax and have a good nap.’

I don’t know how long he went out for but I must have instantly dozed off. When I woke up I felt refreshed. I went out into the courtyard to look round for him. Some distance away I saw him sitting on a flat rock, his back against a large tree. I felt guilty. He really is a gentleman. He would have waited there for as long as it took for me to sleep and feel rested.

‘Mr Kwŏn –’ I called loudly as I ran up to him. From there the conquest of the summit was easily done. The view from there was breathtaking but the summit itself was bare, just a few large rocks and a strong breeze. There was no need to stay long.

‘We might as well go down,’ I said. ‘The pleasure of the moment of a conquest does not last long, does it? Yet for this brief moment of happiness we’ve come all that dangerous way taking hours.’ It was meant to be a casual remark but he seemed to be impressed by it. He uttered a moan-like ‘Mmn,’ followed by a deep sigh.

Following the advice of the people at the temple we took a short-cut down. I found coming down was much easier than going up. I was pleased that it had been such a good day. We walked on in silence for some time. I broke it.

‘What a good climbing course this is. I shall come here often now,’ then went on chirpily, ‘Whose tree, do you think, will do better?’

His response was quite unexpected. ‘No doubt yours will, Miss Yun.’ He sounded solemn and formal.

‘Why’s that?’

‘For one thing, you will come here more often, I suppose.’ I thought he was thinking about his going away to Pusan.

‘Miss Yun,’ he said. ‘While I’m away, will you look after my tree as well as your own?’ His face and voice were so solemn and tragic. What did this sudden change mean? Cautiously I put in ‘Will you be in Pusan all the time from now on?’

‘Well, all being well, I hope to come back within a year or two at the most but...’ he trailed off in a weak voice.

‘It looks as though this is going to be the first and the last time that you and I will come together.’ I added imitating his tone of voice, ‘Mr Kwŏn, would you look after my tree as well as yours in my absence?’

He looked at me with inquiring eyes.

‘By the time you are back I shall be in the United States. I hope to be there by next spring at the latest.’

I hoped he would challenge my phrase ‘the first and the last time,’ by saying something like ‘We can still come together when you are back from America,’ but all he gave was a deep sigh.

‘Whichever one of us it is, each time we come, shall we agree to leave a white stone beneath each other’s tree?’ My mind was full of imaginary incidents like fairy-tales that might evolve from the magnolia tree.

In the middle of a gentle slope not far from the housing estate of Chŏngnŭng, we passed a huge beech tree. Beneath it was a bamboo grove. Out of season the bamboo was not lush but its dry leaves had fallen and were scattered thick all around like straw matting. It looked a comfortable place. No one suggested it, but we simultaneously sat down, leaning our backs against the tree. The sun seemed to be in a great hurry. One could almost hear its striding footsteps as it sets. Trails of smoke from cooking supper drifted over the houses. Feeble light lingered on where we sat. Not a bird twittered nor a leaf rustled in the bamboo grove. Blissful calm.

Then I saw rising on the horizon a mushroom of black cloud.

‘Oh, dear, we are in for a shower,’ I said.

‘Why, are you afraid of gettingg wet?’

‘No, I’m not afraid, it’s just a nuisance to have to walk about in wet clothes. Let’s hurry up and get under some shelter.’

‘No,’ he said sulkily. ‘I want to stay the night here.’ I thought he was being unreasonable.

‘I don’t want to go home. If I fall asleep, just leave me and you go home.’ With this he flung himself down on his back and closed his eyes. He could have been an unpredictable and moody child when he was young, I thought, and smiled to myself. As if coaxing a child I put my hand on his shoulder and gently tapped it. ‘Please stop being silly. Just tell me what you want me to do.’

After a long silence he called me formally, ‘Miss Yun.’

‘Yes, Mr Kwŏn.’

‘Can you recite a poem for me?’

‘A poem?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘What poem?’

‘Anything that might comfort a lonely soul.’

The first thing that came to my mind was a translation of Yeats’ ‘Innisfree.’ I recited it once and having no response from him repeated it once more:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made:

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where

The cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

‘Thank you, Miss Yun. That was lovely,’ he said as if he was awaking from a dream. ‘I have been foolishly wishing that my body was purer so that I could join in a perfect happiness. It has been bliss to be with you for the last few days.’ After a long silence he raised himself and sat upright and said, ‘Would you care to hear my life story?’ I was tense with curiosity.

‘Your youthful vivacity with no trace of shadow gives me the illusion that my dead wife has come back to me.’

‘Dead wife?’ It made me start. Ignoring my surprise he went on, ‘Shortly before I went to America, I used to go to S Girls’ High School as a part-time lecturer. I fell in love with one of my pupils there. I was confident that I could make her the happiest woman in the world. She was not particularly beautiful but had an attractive personality. She made me think of a crock filled with clear water. I loved her for that. But my mother, who is wilful and perverse, did not like her. She could not accept a poor widow’s daughter who was not a great beauty as the wife of her only son. While I was away in the States my mother played all sorts of mischief to make her give me up. The letters I wrote were never once answered. When I came back she was not among the people who welcomed me at the airport. That evening my mother threw a big party to which she had invited many smart young ladies but it all meant nothing to me. Then the telephone rang on the table by which I was standing. She had taken poison and been taken to the Severance Hospital but there was little hope for her. I rushed there at one breath and broke down by her bed, crying uncontrollably. Apparently after seeing me at the airport from a distance she had gone home and committed the deed straightaway.’

I felt my eye-lids smarting as tears rose to my eyes.

‘I didn’t leave her bedside for two days. Miraculously on the third day she came round. After she came out I married her at once. But she was not at all like what she had been before. She had lost all her former vivacity. With lustreless eyes and limp body she carried on for another two months before she died.’

As he came to the end he closed his eyes. I thought he might burst into tears but it was I who broke into sobs. It was not only the dead woman I felt sorry for but my heart ached for him. Beneath his gentle manners, to carry such a sorrow! He opened his eyes and smiled at me. ‘Silly Sukey, you are crying. I’m sorry if I have upset you. Shall we go now?’ He pulled me up by my hand. When we came to the house where I lived with my sister in a rented room, he put out his hand for mine, which I readily gave him. He held it tenderly in his hands and said, ‘Good night. You must be very tired,’ and added, ‘Can I see you again tomorrow or would you rather stay at home and have a rest?’

I didn’t know what to say. Two more days and he will be gone. I wanted to make the most of the time left. On the other hand, I was really tired. I thought I needed a day’s rest to be at work on Monday. Just then I heard some one moving behind the gates. I quickly pulled my hand out of his grip, said in whisper, ‘I’ll see you at the usual place at eleven’, and ran into the house.

6 April. 3 a.m. I have been lying awake all this time. My limbs and whole body ache and I am dog-tired but sleep would not come. Like a pond disturbed by throwing a stone in it, I cannot calm myself. At the temple, he went out of the room so that I could relax and rest while he waited outside. He could love, with such faithfulness, a plain-looking woman with poor background. He is a man of few words. Most of the time he lets me dominate the conversations with trivial matters while he just looks on me with admiring eyes. He has some respect for women. He is a personification of goodness and truthfulness. If he wants me I think, I shall give him the whole of myself at any time. In this way am I sealing my fate? Yes, I am ready to accept my fate if it is that.

I finally dropped off after more or less making up my mind. Once gone off I slept soundly. When I woke up it was half past ten. I got myself ready in a great hurry, omitting the breakfast, and got a taxi to ‘Rose’. Even so I was half an hour late. Leaning back on a chair he sat with closed eyes. As I sat opposite him with a guilty look he opened his dreamy eyes and said, ‘So you decided to come?’ There was no need to explain why I was late. I just smiled.

‘I knew you were tired, but I thought you may not want to see me anymore, a worthless man like me...’ He did not look as sad as he had yesterday so I stopped him briskly. ‘No more moping, please. It’s too nice a day to be stuck in a dark corner of a tea-room. Let’s get out of here.’ This seemed to cheer him up.

‘I thought a day at the seaside would be nice, after a day in the mountains, unless you are too tired?’

‘A day in the mountains followed by a day at sea! How wonderful.’ I gave him an admiring look as I clapped. ‘Where will that be?’

‘Inchŏn would be just right for the time we have. It’s already twelve.’ He stood up and went to the counter to pay. He had a camera slung over his shoulder, and looked very smart from the back. I was proud of him. On the way to the bus terminal, I was slightly taken aback when out of the blue he asked, ’By the way, what sort of salary do they pay you?’

I teasingly said, ‘A gentleman asking a lady about her salary!’

‘It’s just that I am thinking of taking on an assistant and wondering how much I should pay her.’

‘Seventy thousand Hwan.’

‘That’s not bad, is it?’

‘Besides, we get a quarterly bonus of the full amount.’ He thoughtfully nodded his head.

The seat for two on the bus was not quite big enough to be comfortable. We sat side by side, our shoulders touching. I felt as if I could feel his warmth coming through my layers of clothes, but soon I realized that I was the only one who was so self-conscious. With his eyes fixed on the view through the window and his hands on his lap, one on top of the other, he sat correct and upright. Outside was mile upon mile of barley, the blades of leaves sparkling in the bright sun. When the breeze rose and ruffled them, they fell flat on one side and then the other, ripples of green waves through which our bus sped like a speedboat.

In no time we were at the beach. He arranged me in various poses and clicked his camera. The tide was low. In silence we walked over the sand toward the water’s edge. It made me think of travellers setting off towards the far horizon, long, lonely shadows dragging behind them. He was very attentive to my moods. When I was just thinking of a rest, he stopped and made me sit against a large rock facing the sea, pressed the shutter once again and then came and sat beside me.

Far out the tide had turned. Myriad of seagulls hovered over it. In a rhythm of ‘pull, rest, smash!’, ‘pull, rest, smash!’ the waves surged and shattered like explosives. We sat in silence, each in their own thoughts. Mine dwelled on the love and wondered whether it did not resemble the waves, in its force and its single passion. Once started rolling it won’t stop half way. It will go on and on until it reaches the shore and smashes itself.

In no time the water was almost below our feet. He stood, took a step closer to it and mumbled as if to himself, ‘The water that ebbed is flowing back but...’

‘You mean ’the one who departed is not?’’

‘Sukey, you are too clever for me!’ I rose and stood beside him and we both took a deep breath. It was a full tide.

‘Sukey.’

‘Yes?’

‘I’ve decided on something.’

‘What thing?’

‘Not to think about her anymore.’

‘It is not the sort of thing that you can do or not do at will, is it?’

‘What I mean is that the face I have remembered everyday for the past three years has recently become blurry. Even if I try hard to evoke it, I cannot bring it back.’

A silence fell. I thought of the poor woman. Then he said, ‘It is thanks to you that I am beginning to live my life.’

‘Oh, no,’ I thought, ‘He is going to propose.’ His face was tense as it was yesterday, at the temple. I knew I was in love but I was not ready to make a decision right there and then.

‘We are going to miss the bus if we don’t hurry.’ I gathered up my handbag and the litter from our snack. Without any fuss or protest, he followed me.

‘It has been a lovely day. Thank you, Mr Kwŏn.’ I knew we had got over another dangerous moment. We were now happily chattering about trivial things.

He said, ‘You must be fond of the colour of the sea. I like your dress. I often think of you in that sea-blue ch'ima and jogori at the hotel. It reminded me of a kingfisher skimming over cool and clear water.’ He went on, ‘There was a lake not far from my college in the States. My professor often took me there for a drive or on a picnic. There was this beautiful water bird. It used to dart about over the surface of the water making merry, chirping sounds. It had feathers of that colour.’ Again about the States. I was dying to ask him what he studied, and where, and how long but refrained in case he thought I was too inquisitive. I smiled to myself as I remembered what a goose he had been at the hotel in his white and blue striped pyjamas.

We stopped briefly to turn round and cast a last glance to the sea.

‘Sukey.’

‘Yes?’

‘How old are you?’

‘Twenty-four. What about you?’

‘Thirty-one.’ Then we looked at each other and burst into laughter. Thirty-one. Suddenly the thought of my brother, Hyŏngsŏk came to mind. He would be just that.

7 April. We are now confessed lovers. This is how I had wished it to be. He leaves for Pusan tomorrow. Before he went, I had hoped, we should make some kind of binding pledge tonight. I am too excited to write down what happened today.

When he phoned me during the morning I expressed my strong wish to see him off at the station after work tomorrow and he said he would change his plan so as to leave at seven-thirty in the evening. But when we met after work, he apologized that after all he had to go in the morning as he would be with his mother and she had already bought two plane tickets. I am afraid I can’t think kindly towards her. She sounds a bossy, mischief-maker, and keeps him under her thumb. Of course I told him I did not mind not seeing him off. Unfortunately the Board meeting that had started at four-thirty dragged on until seven-thirty and it was not until nearly eight that I was with him. After dinner, a farewell dinner, we went out to the Han River by taxi and walked along the sandy beach. After a group of late fishermen had collected their tackle and gone, we were the only ones left on that vast shore. Like two dreamers we walked hand in hand, vaguely, towards the lights from the houses in a distant village on the other side of the river. The damp air rising from it felt quite chilly as I was wearing only a thin spring dress.

‘Sukey, aren’t you cold?’ He lightly touched my cheek.

‘No, I am alright, thank you,’ said I but somehow I stepped closer to him and into his arm. From then on we walked with our arms round each other’s waists. He again spoke of how he wished his body was purer, and asked me what I thought about love and whether I thought one should be allowed to love for the second time? I knew what he meant. He wanted my approval for his second chance to love. I had never thought about it much but words just tumbled out. ‘Of course one can love for the second time, the third or even the fourth. Why ever not? I’m sure love is not a matter of the past or future. It is whether or not you love someone now; whether you can wholeheartedly keep faith with the one you love, a matter of conscience perhaps...’ He did not wait for me to finish but gathered me in his arms and kissed me. In accepting this I felt as if a large column that had propped me up until now collapsing and, leaving a huge hole. As if to fill up that emptiness I attached myself tightly to him for a long time.

‘I feel worthless and shameless to ask this but will you marry me?’ he said and without a moment’s hesitation I nodded my consent. I had well prepared myself for this. By doing so I have sealed my life!

We must have walked for miles. The lights that once looked so far away were now just opposite us on the other side of the water. We could have gone in a state of daze. I was dimly beginning to think it must be very late. Suddenly a sharp breeze from the river came and slapped me on the cheek. I pulled away from him. ‘Let’s go home, I’m scared.’

‘What are you scared of? We have plenty of time,’ he protested and sounded irritated. ‘And it is the last night before we see each other again!’ But I shook myself free. ‘I am going to catch my death of cold!’ I started off towards the embankment.

Come to think of it, he was very annoyed even though he was too much of a gentleman to show it. He said, when we bade our final goodbye, with less certainty than earlier, something about sorting out some business in Pusan and coming back to marry me very soon. I don’t know what to do. I am all in a flutter. Even though I am thrilled I am sure I am not ready for an early marriage. Still we can think it over, can’t we? It is my daily blessing to water and see the pointed buds of the lilies of the valley push their way through, a little bit bigger each day, like the promise of bright and happy days.

9 April. I am a fallen woman. Let the world laugh and mock at me!

Yesterday, when I got to the office, Suyŏn handed me the phone and said, ‘It is the fourth call for you, always the same voice.’ She seemed to sense it was something special and left the room.

‘I knew you weren’t be there yet, but I wanted to hear your voice so much that I have been ringing you since I woke up. Silly, aren’t I?’ He chuckled. ‘I am just about to leave for the airport.’

We had gone over everything that we had to last night. I didn’t know what to say except ‘Take care of yourself, and please keep in touch. Goodbye.’

Ten minutes later the phone rang. It was him again. ‘Mother is not quite ready. I just wanted to say that I love you so much. I can’t bear to leave you. Shall I not go?’

I was touched but thought him unmanly. ‘Don’t be silly. You sound like a little boy.’ But when he actually put the phone down saying that his mother was just coming out, I was sad and held onto the receiver as if expecting to hear his gentle voice still vibrating.

When two hours later he phoned yet again I was taken aback. He was being ridiculous, I thought. We have made a pledge to each other and we know that we’ll meet again soon – what is there for him to be so restless about. He said he had something important to talk over with me. So, at the airport he parted from his mother and came back. I felt a momentary disillusionment. One can be infatuated when in love but this was going too far. I also felt ashamed about what had happened the night before by the River Han. When I see him tonight, I thought, I would suggest that we ought to calm down a bit and carry on our love in a more dignified and rational manner as befits intellectuals.

On the other hand I was uneasy about the ‘important matter’ he was referring to. What could be so important that he should go as far as to cancelling his flight? I was again detained at work. So it was nearly eight o’clock when I met him at the appointed restaurant. When we had ordered our meal, he started by saying, ‘I was nearly trapped into my mother’s plot.’ Behind his back apparently, she had been arranging his marriage to the daughter of a business tycoon in Pusan. It had been his mother’s intention to introduce her to him in the evening. As his mother sensed something was going on between us, he had guessed, she might plan some mischief against me. He had to warn me of this in person. He would go to Pusan tomorrow to sort out a few things, staying away from his mother, and come back on the 12th to discuss our marriage arrangements.

I felt as if I had been hit on the head with a hammer.

‘Our love and trust in each other will win in the end, blah, blah, blah’ he went on talking something like this but I couldn’t hear a word. When I recovered my senses I felt bitter. So, his mother is against me, is that what he’s saying? Am I not good enough to be his wife, a second wife? Who does she think she is? How dare she? Outrage made me feel like screaming but I kept a calm face. Why, in the first place, had he not introduced me to her before he made any advances? I had so much to say but words failed to come out.

‘Mother produced this out of her handbag on the way to the airport.’ He handed me a photograph, the size of a visiting card, of a beautiful woman. It was rubbing salt into my injury. My hand shook with jealousy on top of the outrage. I was dying to hurt him to the quick by words or deeds or both as revenge for my pain. I handed it back to him and said very calmly and clearly, ‘That’s the best thing that can happen to you. I haven’t the slightest inclination to enter into competition with this woman or fight your stupid mother. Goodbye.’

I walked out of the restaurant and briskly and blindly set off down the road ahead me. When it turned out to be the way to the River, I sharply changed my direction to shake off the memories of last night and took another course. I don’t know how many turnings I had taken before I found myself going in the direction of Tonamdong. When I was close to home, I turned back again. I had been weeping and could not go home with a tear-stained face. I had been aware of his footsteps behind me for some time now. When I veered into a cul-de-sac they quickened and as he snatched me into his arms I broke down and cried.

‘I didn’t know you were as weak as this,’ he said. ‘As long as we are sure of our love, what is there to be afraid of?’

I was calm when we resumed our walk. He talked about various possibilities about our future, living away from his mother. For instance we could go and live in Cheju Island. A close friend of his is running a large dairy farm there and would welcome him any day as a business partner.

‘But you must be starving, silly girl,’ he said. Indeed I was. I was cold too, my teeth were chattering. We went into a shabby soup place, which was about to close for the night. We ate a bowl of meat soup each. When we came out the preliminary siren for the curfew was sounding. He caught a taxi just rushing by. I leaned on his shoulder and closed my eyes. It dropped us in front of a hotel. I could not believe my eyes. The prolonged shriek of the siren for the curfew shook the black night. With a keen grasp of the situation, like a well-trained dog, the waiter said there was just one room unoccupied. Once in the room and the door was locked from the inside the inevitable took place. I could not blame him entirely but I was certain that we disgraced ourselves. It was not a proper way to go about love. My lofty pride was thrown down onto the ground and trodden on. I was quietly weeping but at least I was sure of one thing – nothing could now separate me from him.

This morning I was too ashamed to face the world let alone my colleagues. I sent in a message that I was unwell and came home. I had to invent a lie for my sister. I told her that his mother and sister were so keen to meet me that I went to his house, enjoyed myself very much and did not realize how the time went until the curfew siren went.

A face floated before my eyes all day. It has superseded the entire world. What would I not give to have it by me now. In the afternoon I went to see Miae. We hadn’t seen each other since her engagement party on 30th March. She was wild with delight when she saw me.

‘What a super surprise! You’re still alive then? What wind brings you here?’

‘Silly cow! Who’s talking? Why couldn’t you drop in while you were in town? Anyway, that was a splendid party, wasn’t it?‘

‘Did you enjoy it? Thanks a million for all the things you did for me that day.’ We heartily enjoyed our reunion.

‘How is Mr Han? Has he got a job yet?’

‘Yes, at X Bank. He’s just started – last Monday.’

‘That’s good.’ I took off my shoes and entered the room, which seemed to have been converted to a sewing room. A middle-aged seamstress from the country was deftly turning the wheel of the sewing machine.

‘What’s all this? You haven’t even fixed the wedding day yet, have you?’

‘Well, I’d like it to be in the autumn but apparently his mother wants to have it done before May. In any case, my mother thinks it would be best to have everything ready in good time.’

We walked upstairs and stood on the verandah overlooking the garden with its thriving shrubs and trees. Her father’s transport business must be thriving to have bought a house like that in an expensive, residential area. As I rested my gaze on one end of the evening sky I was comparing the rising fortunes of her family and the declining luck of my poor father. I envy her. I live on a tight budget. Buying ordinary clothes to wear at work is hard enough let alone getting a trousseau ready! What am I to do?

Miae was very happy. She told me that she had started learning to play the kayakŭm. I asked why out of all instruments she had chosen that.

‘It’s Han’s favourite apparently,’ she said. ‘He says he can’t take to noisy Western stuff, and would like to see me plucking the strings of a zither in a traditional full skirt of pastel-coloured gauze. Funny, isn’t he?’

‘It sounds a very refined taste,’ I said as I turned to face her. ‘Miae, don’t laugh, but I may even beat you to it.’ I needed courage to bring this up.

‘What? With Mr Kwŏn?’ She was surprised.

‘Umn.’ My mood of melancholy of a few moments ago had completely cleared. I told her about everything except what had happened in the hotel – a day in the mountains, a day by the sea and the night stroll by the River Han. As I did so my heart ached with love for him.

‘You sneaky minx! So you’ve gone through it all.’ She clapped her hands and rolled in laughter. We chattered on like this for sometime.

‘So what is going to happen now to our beloved study?’ Miae said. It’s true, our studies have been our lovers. Books and dreams have set us apart from our friends and contemporaries. There had been little room for men in our hearts.

‘Of course, we are not going to abandon it altogether, are we? Let’s carry on,’ I said. ‘We have to be different from the others. Probably, I shall go to post-graduate school next year. I fancy a transfer to English literature. Then in a couple of years’ time, I would like to go to America preferably with him...’ I said this with confidence then but now I feel less certain. The thought of his mother bothers me.

10 April. I have been counting the ticking of the clock virtually all day. Counting down for our reunion had started forty hours too early. Forty hours, thirty-nine... After work I went to Chongro 4th Street and roamed around the district for nearly two hours hoping to find his house. I looked into every alley, but could not find one that fitted what, from his casual remarks, I had imagined it to be like. It’s foolish of me, of course, to set out in search of a house without knowing the number or the name of the head of the family. But then I didn’t mean it seriously. Even if I had found it I would have had no courage to knock on the gate or anything like that. I just missed him so much. I would have been happy just to be around the house that he goes in and out everyday. Finally I knocked on the door of the District Office, which keeps open late.

‘I am looking for the house of a man with the name of Kwŏn. He lives around here, I am certain about that. He’s a lecturer at S University, his father is a businessman, his mother owns a number of buses, and by the way, he has a sister who is a student of E University...Would you happen to know such a family?’ The clerk gave me a pitying look. ‘You might ask for Mr Kim of Seoul City. You won’t find a house in that way.’

I don’t blame him. I turned round with giggles. What an idiot I am! I shall tell him when I see him. It will make him laugh.

11 April. Overnight the world has changed. It’s wrapped in layers of suspicion. My head is filled with cotton-wool-like substance and I can’t think clearly. ‘Social evil’ is a familiar term I hear almost every day of my life, but I have little experience of it myself. Probably my world so far has been too secluded. I have no immunization to it. Still, how can you doubt such a good and sincere man and place him in the context of social evil.

Miae’s advice was from the bottom of her heart, I know, but sadly I see that a chasm has opened up between us. She had called me in a cheerful voice just to say hello but when I told her what I did last night her tone changed.

‘When you decided to go and look for his house you must have had some idea of its whereabouts, near some landmark like a big building or a shop or a large chimney. As you know I had lodgings around there once, and as far as I can remember I can’t imagine a big private house tucked away anywhere among all those shops and shop-keepers’ houses in that area.’ Once again I appreciated her rational mind in contrast to my woolly and emotional temperament.

I hesitated for a few seconds but had to tell her about the phone calls too.

With longing and peculiar curiosity I had dialled the number he had given me. If anyone answered I would just hang up. If someone sounded nice and said hello before I put it down, I could simply say that I was a student of his and could I speak to him. It rang. I was all nerves. No one answered it. It was a relief. I tried again and again through most of the morning. I was beginning to be irritated. In the end, I phoned the enquiries and was told that the number was not registered. My heart missed a beat.

The bell in the Director’s Room rang. I was unable to stand up. So Suyŏn went in on my behalf. I gritted my teeth, got the number for S University and dialled it. The operator’s kind voice said, ‘I am afraid most teachers are away because it is still the vacation.’ Like a drowning man holding onto a straw I interpreted it as a positive admission that he belonged there. I asked to be put through to the Registration Office and confirmed that he was not on the teachers’ register. I wanted to die. I crawled into the conference room and collapsed onto the sofa. Suyŏn came in bringing in a cup of coffee.

‘Good heavens, ŏnni! What is the matter? Should I call the doctor?’ She was in a flutter. It was then that the office-boy put his face round the door and told me that Miae was on the phone.

‘I think you should stop seeing him before your affection for him grows any deeper,’ her voice was now decisive yet solicitous. ‘What is the use of loving a man who lies to you whatever reasons he may have.’

She does not know the thing that I need to hide from the world. How disillusioned she will be when she knows it. Something like a lump of lead in my throat was choking me. I could not speak.

‘Han has some friends working with the newspapers and in the Police as well, the Criminal Investigation Section in fact. I have a good mind to let them investigate the case and teach him a lesson.’ Her voice was now cool. But such words as newspapers and criminal investigation made me cringe. I could see before my eyes such headlines as ‘Professional Fraud – Fake College Lecturer Seduces Female Graduate.’

‘Please don’t tell Han, Miae. I will make another investigation and sort it out myself.’ My voice sounded cowardly, as if appealing for her mercy.

‘Alright then, I won’t. I will trust in your good sense,’ she spoke curtly and rang off. I still can’t believe he’s a fraud. He must have had his reasons. Until I know them I can’t just dismiss him like that.

It is late but I can’t sleep. Unable to bear it alone I told my sister the whole truth. I thought she might slap me in the face but she took it with unexpected calm. ‘I am going to be ill,’ she said before she went to bed, pulled the cover over her head and sobbed. She’s now asleep. I have a feeling that he will never appear before me again. My love – has he gone forever leaving sorrow in my heart? Leaving the saplings of magnolia and the buds of the lily of the valley as the only proof that he was there? The rapture of yesterday turned into sorrow today. Why did he do that? Why did he have to deceive me? He didn’t have to lie. I would have given him my all without all these lies. I am thinking of taking my life.

12 April. Sŏnhi is ill. Every time she has a shock she seems to go down with sickness. She needs several days’ quiet. Whether he will come back or not I have a duty to my work. I thought I ought to clear up all my drawers and files to make it easy for my successor after I have gone.

In the afternoon, the Director went out to go to the X Foundation leaving his office for an hour or so. ‘When the cat’s away the mice will play.’ My colleagues behind the partition broke into lively conversations. Mr Hong banged on the partition and shouted, ‘Miss Yun, how long?’ meaning how long will he be away.

‘About an hour,’ I said. Long enough to pool a small sum of money, and one of us go out and get some snacks. In normal circumstances I would have joined them chattering as loudly as anyone else, but today I went on with tidying up my drawers. Miss Pak came round to me.

‘Are you all right? You don’t look well.’ I like her sisterly ways towards me. She pulled up a chair by my side and was about to say something but on second thoughts closed her mouth.

‘So, Miss Chŏng’s going soon, then,’ I had to break the silence as I was the hostess and she the guest.

‘Yes, isn’t she clever? She has arranged it all so quietly with no fuss, no showing off.’

‘Having her sister and brother in America must have been a great help, I suppose. I shall miss her.’

‘So will I.’ Then she said, ‘What about you? With the man you met in Onyang. I thought you were getting on well with him for a few days?’

I didn’t know how to reply. Two days ago I would have said, ‘We are going to be married soon,’ and told her all about it.

‘Um, we are in love with each other. He’s away in Pusan at the moment.’

‘Good. What’s he like? ‘

I could not hide my tears rising to my eyes. ‘We love each other but he has a wife and a child.’ At this rate, I shall soon be a master liar myself. There was now no need to restrain my tears.

‘Oh, I am sorry.’ She heaved a sigh.

‘Ŏnni, don’t tell anyone, will you.’

‘Of course not, but I am terribly sorry. Try to forget. You couldn’t have developed too deep an affection yet.’ She clicked her tongue as she left me and went back to her desk. At that moment the telephone rang.

‘Hello.’ My voice sounded weak. A woman’s voice said, ‘Is that Miss Yun I am speaking to?’

‘Yes, I am Sukey Yun.’

‘That’s handy,’ she said. What an arrogant voice. ‘It is about Tong-hi Kwŏn.’ I tensed up. At first I thought it was his mother.

‘You had better give him up. He will not be seeing you today. I’ve been with him in Pusan.’

‘May I ask who you are?’

‘You don’t need to know who I am, but I am telling you this for your own good. All I can say is that I loved him before you and I trust your good character.’

I could not make sense of all this and I was thoroughly confounded. Then a few minutes later the phone rang again. This time it was him.

‘Oh, Sukey. I’ve just got off the train and run up the stairs in one breath.’ He was obviously panting.

‘How are you? You are quiet? Sukey? Sukey?’ I didn’t know how to respond to this. On hearing his voice all my suspicion and anger melted away, I could not wait to see him. If I was honest to myself I should have said frankly, ‘You have been lying to me. Liar!’ But I had developed some cunning in the last few days. I have learnt to handle certain circumstances with caution and strategy. If he knew that I suspected him and was angry he might decide not to see me again. I could not risk letting him slip away. I pretended innocence and cheerfulness.

‘So, you are back. Did you have a good time? How’s your mother?’

‘I have so much to tell you. I’ll see you at “Rose” at seven.’

When I saw him the expression on my face probably betrayed a mixture of hatred and love. He looked a bit thinner. I thought I would sort it out there and then, the questions of love or deception, and life or death.

‘You have been lying to me. Why?’

Like a deer struck by an arrow his countenance instantly crumpled. ‘I knew you would be like this.’

‘But why, why did you have to deceive me?’

‘Please say no more. There are reasons, which I hope to explain to you in due course. All I can say is that only our love can solve all the mysteries,’ he said imploringly. I noted with curiosity his words ‘There are reasons.’

‘I left home today,’ he said. We looked at each others’ blank eyes.

‘I haven’t eaten anything all day. Shall we go and eat first and then I will tell you all about it.’

We sat in a Western-style restaurant and ate our meal in silence. I could see his hands holding the knife and fork were visibly shaking.

I was taken aback when what he called his new lodgings turned out to be a room in a small hotel. Since that night I had come to harbour bad feelings about such places. In the room there were one suitcase, a small writing desk and a small transistor radio on top of it. The ondol floor was pleasantly warm, over which his bedding had been neatly laid out. An elderly inn-keeper and his wife came out and offered him a courteous greetings and went away. Music floated from the radio.

‘I want you to understand this, Sukey. I have thrown away all the comforts of life for your sake,’ he said as he gripped my hands. ‘You trust me, don’t you? I will tell you everything tonight.’ His face was full of love, enough to melt away the last trace of suspicion and anger. As my tension loosened my body became sloppy. Languor came over it and I could barely sit upright. I felt like throwing myself into his arms and abandoning it to his caresses.

A beep came from the radio. It was the time signal announcing nine o’clock. It was like an alarm bell to shake up my numbed reason. ‘You must not allow yourself to spend the night here.’ It was a stern voice of my conscience. I sprang to my feet. ‘I must go now. See you tomorrow.’

‘What do you mean?’ He was confounded. ‘No, you can’t do this to me. I won’t be left alone.’ He whispered like a feeble child at first. But when he saw me putting on my coat and picking up my handbag he stood in the doorway blocking it. ‘If you go, I shall leave Seoul tonight and never see you again.’

‘My sister is very ill.’ I pushed him aside and stepped down to the courtyard. ‘Good night, Mr Kwŏn. I will see you at “Rose” at ten o’clock tomorrow.’ I did not wait for his reply and ran out of the gate.

When I was finally through the long alleyway and stood at the edge of the main road I saw him coming after me calling ‘Sukey, Sukey.’ Like a lunatic I ran across the road stumbling forward and stepped onto the pavement on the other side of the road. Now we stood opposite separated by a dark main road like a deep river. As I stood there I repeated to myself, ‘Please forgive me, please forgive me.’ I had to get on whatever came first, taxi or bus, but it was a quiet road and nothing came. From the pitch black sky, drops of rain began to fall. His body standing on the other side of the road like a statue started moving towards me. He was coming to implore me once more to stay with him.

‘Father, save me from this moment.’ Unawares, a prayer leapt out of my lips. I repeated it again and again. He was half way across the road when an empty taxi came sliding round the corner and stopped before me as if in a response to my prayers. Its door briefly opened and shut and it slid away. A scurry of rain beat on the rear window. He stood rooted on the spot. I desperately waved at the rain-splashed back window but whether he saw me or not, he did not return it. The car turned a corner. ‘Poor man. He will be wet through standing there fixed on the spot.’ I felt heartless. ‘He will never appear before my eyes again.’ At this thought I burst into tears.

13 April. When I woke up I knew this was the day on which I had to make a final decision. As if I were faced with a difficult maths question my mind was clear and my mood just rightly tense. By the time breakfast was over my mind was made up. ‘He is not a common fraud of no conscience. He must have some reasons. There is no doubt about his love for me. As long as I can trust that he is not a villain I will forgive him and help him out of his trouble.’ I wondered whether he would turn up now that he knows I suspect him.

‘You’d be wise to take my advice. You shouldn’t go. There is no need even to reconsider it. He’s a liar and that’s that.’ My sister had been coaxing me all morning but when I said to her ‘I won’t be long,’ and set off she exploded in anger.

‘If you are not back by midday, mark my words, I will kill you and myself.’

He was waiting for me. I was thankful but not in the mood for a cheerful greeting.

‘How’s your sister?’ he asked with a rueful face.

‘She’s not too bad. It has been too big a shock for her delicate nature. From our childhood, I have always been a cause of worry to her.’

‘She must hate me. Can I go and see her today?’

‘Well, she’s virtually my guardian, so you should but...’ I could not say that she hated him. Besides I wanted to get on with the business to hear his explanations, consider them carefully, draw my conclusions and go home to look after my sister.

‘Do you know any quiet place where we can go to and talk things over?’

I felt like ridiculing him by saying, ‘What fantastic secret do you harbour to need such a place?’ But I refrained.

‘You are quiet today. Where would you like to go?’

‘We’d better go to the Secret Garden, then,’ I said. It was only partially open to the public but I had a special pass.

Once the residence of the kings, the Royal Palace Gardens were now as quiet as a tomb shrouded in a mystic atmosphere. Ancient trees, their trunks as thick as several arms’ span, stood with solemn dignity like sentries. I thought of them as witnesses to the lives of the generations of kings and queens and their attendants who had strolled here weaving multifaceted human dramas. As we passed beneath them I fell into a fantasy that for every word I uttered and every footstep I took now was like planting seeds that I would reap some day in future. The azaleas and the forsythia now at their peak were in delighted coquetry with the fresh, glossy leaves of the shrubs.

There was no human sound around. Only the chatter of birds as they darted in and out of the trees and bushes. We walked in silence through the woods looking for an even more secluded spot. Being in the middle of a wood with not a soul around inevitably made us feel closer. At last we stopped beneath a huge beech tree. I had noticed that he always carried under his arm a large brown envelope filled thick with papers. You could see from the open top that for the most part it was manuscript paper. After rustling through them he produced a folded white paper and handed it to me. It was a long poem. I sat down as he directed on a seat he made for me with layers of newspaper and his handkerchief on top. I read.

Star-counting Night

The sky through which the seasons pass

is full of spring.

With no fears or worries, I think

I can count all the stars, the stars of spring.

One by one, they are impressed

in my heart. And,

If I fail to count them all

It is because the morning is drawing nigh;

it is because there will be another night tomorrow;

and because my youth is not yet finished.

To one star, memories

To another star, love

To another, forlornness

To yet another, yearning

To another, poetry

And to another, mother, mother,

Mother, I give a sweet word

to each star. Names of the girls

Who shared the desk with me at junior school,

Names of foreign girls like Pai, Kyong, Ok;

Names of the girls who have already become mums;

Names of the poor neighbours; a dove, a puppy, a song, a deer,

and names of poets like Francis James, or

Rainer Maria Rilke.

They are far away

Like the remote stars,

And you, mother, are in North Chianto.

With a yearning heart for a certain thing

I inscribed my name on the ground

of a slope on which descended

The starlight from the many stars.

And then, buried it over with the earth.

Do you know why

The insects chirp all through the night?

They are sorrowing for the shame of that name.

But when the winter is over and

spring comes to my star,

Like the grass on a grave revives green,

On the slope where my name is buried

Grass will thrive with pride.

1958. 4. 12. K.

When I finished reading it he calmly gathered me in his arms. The sad and beautiful spirit of the poem had moved me deeply. A man who can write a poem like this can’t be a bad man, I thought. I was overcome by a great sense of relief. I held onto him tight. I was ecstatic, but it was after hearing his confessions that I became even closer to him and resolved that no amount of suffering or even death could separate us now.

‘Sukey,’ he called as he held my face in his palms and looked into my eyes. ‘By telling you this I am putting my life in your hands.’ He went on looking into my eyes.

‘Do I not look forlorn?’

Yes, he did look forlorn and pitiable. He made me think of a deer having a momentary rest behind a rock, after losing its mate on a hunt and still being chased by the hunter. His eyes were filled with fear and loneliness. I nodded. The lingering emotion from the poem I had read a minute ago made my heart ache. It echoed like the sobbing of a soul that had been separated from its loved ones, roaming in a dark valley of desolation, and cherishing a remote dream. Then it crossed my mind. Could he be? I shot at him a questioning look.

‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘I am a lonely man with no family. My home is in Hamhŭng in the North, My real name is Changho Yu.’

My heart missed a beat but I did not show him my surprise or embarrassment. I am known to be cheerful and tomboyish, but when faced with a crisis or a shock I am extremely calm and self-possessed. That is my peculiar characteristic. I calmly heard him through to the end.

He is the only son of a high-ranking government minister in North Korea. His family had lived in Seoul before the country was liberated from Japan in 1945. In that year he graduated from Kyŏng-gi High school. After that his family went North. There he studied law at the Kim Ilsung University and went to Moscow University where he gained a Master’s degree. He was noted as a capable man by the Central Communist Party and eventually appointed a leading figure in an underground operation in the South. He was not keen but knew he had no choice. If he had refused to go he would be killed anyway. So why behave in a cowardly way? When it was finally decided, his intellectual mother, a graduate of the Japanese Women’s University, went for a month without food or sleep.

His father, a strict disciplinarian from the army told him at the last moment, ‘Changho, your country demands this of you. If you save your life in a cowardly manner, you are not my son, remember that.’ In the previous year, he had entered the South through Inchŏn, leading a group of three men, all of his age. He had successfully completed his mission. It had been fairly easy. His only remaining task had been a safe return. Then he saw me, fell in love at the first sight and decided to give up the idea of going back.

‘I went to Pusan and bade a final farewell of my colleagues. If only I had got into that jeep, I would be home by now. They were very fond of me, like a big brother. To the last minute they pleaded with me to change my mind but I said “no”.’ His large, expressive eyes closed as he said, ‘When the jeep started moving, strong-willed as I am, I could not help tears rising to my eyes.’

By now I had come to fully realize the situation. I was having an affair with a spy. Fear gripped me. I was shaking despite my effort to be calm. He went on to explain his position. As for his own security he was absolutely confident. He belonged to an extreme elite group completely different from those that had infiltrated spies in the past.

‘They are blind idiots. It beats me how they can be so stupid. To send down spies in chains in a time like this. If one is caught, the rest are bound to be hauled up like a net of fish,’ he said contemptuously. ‘I won’t tell you the details because if I did, it would only upset your sensitive nature and cause you unnecessary distress. Just trust me. I would not have started this if there was the slightest risk.’ He went on, ‘The most important thing is that we have left no clues behind whatsoever, not so much as the tip of a hair.’

I had no wish to know anything about it. On the verge of a nervous breakdown as I was, I felt I needed protection from knowing one more fact. I weakly smiled to myself as the phrase formed in my mind, ‘Blessed are the ignorant for they shall be spared of worries.’

He was also sure that his financial position was fairly good. The remaining fund from their operation amounted to some five million Hwan, which was in the hands of some practitioners of Chinese medicine in the form of the medicinal material. He could draw on it gradually as time went by. Then one day the country will be reunited, he believed, within three or four years at the most. It has got to come in one way or the other, or the country in a state of strangulation as it is, will just fade away.

‘There, I have told you all. I feel such a great relief. I have long wanted to be delivered from such a dreadful life. All I wanted was to lead an ordinary family life with a good wife like you. However, I won’t blame you if you report on me.’ Whether he noticed my nervousness or not he went on, ‘You are all to me. I don’t mind dying so much. Just that I have had you for a few days makes me the happiest of men.’

Then something crossed my mind. According to his account I must be the only woman who knew him in the whole realm. Who was that woman who rang me yesterday? I told him about it expecting he’d be surprised but he gave his charming chuckle.

‘Ah, that. I arranged it. She’s the maid at the inn where I am lodging at the moment. I hope to stay on there, you see. It was a way of proving my identity.’ I must say, I was impressed by his meticulous planning.

A long silence fell. As though even the birds were tired of calling to each other, the entire wood was as quiet as death. The only sound was the rhythmic booming of my heart. It was the sound of the engine of a ship that was about to sail and change the course of my fate regardless of my own will and wishes.

I closed my eyes. I was to listen to the voice of my conscience and to decide on the course of my action from now on.

As an individual, I have lived a very happy life. I certainly belonged to the privileged class in my country. At school I was a studious, exemplary pupil; at work an exemplary employee working hard and conscientiously; and in society a law-abiding, responsible citizen. Along with all these favourable conditions, I passionately love my country. The patriotism that has been bred into me ever since my childhood flows through my arteries never ceasing. Would I ever dare to commit a deed that betrays my motherland? A spy, an enemy against my country – could I love such a man?

I opened my eyes disturbed by a rustle. A squirrel had come up from somewhere and was staring at us from just a yard away, probably puzzling out whether we were some still objects or living things. We had been that still. I looked up at him. Expressionless, his eyes and face showed he was very tired.

‘Poor man!’ I was overcome by a sudden upsurge of emotion of pity.

‘Even spies must have basic human goodness and conscience.’ I began with this hypothesis. He has his beloved mother and father back in his home. How much he must have missed them, especially his mother who went without food or sleep for a month for the worry of her beloved son. On autumn nights when the moon was bright and the crickets cried all through the night did he not cry himself to sleep for the love of his mother? Knowing perfectly well what kind of punishment awaits him in this country, he chose to remain here for his new-found love’s sake. What a fairy-tale-like story!

What will become of him if I now abandon him? There is no doubt that I love him. We are not, by origin, aliens to be afraid of each other. Due to an unnatural division of the nation we now belong to opposite camps but surely this is not going to last long. One day soon we will be one nation and we could be lawfully married husband and wife. He says he is completely freed from his past commitment. Our love for one another can be in no way against human conscience. Apart from the political past, we can establish a happy relationship.

‘You can’t undo what has been done, but are you sure that you won’t be swept into it again?’ This is the only guarantee I wanted of him at the present.

‘I swear in the name of God,’ he said.