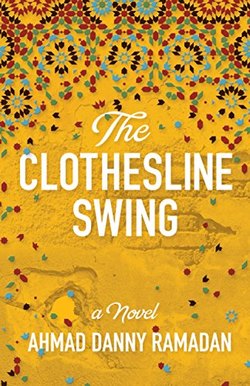

Читать книгу The Clothesline Swing - Ahmad Danny Ramadan - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

The Hakawati’s Tale of Himself

There are tremors around us; it’s like an unwritten piece of music. That hidden melody is creating a routine for us. Every action we take in our lives is like a gentle touch on the strings of a violin. We create a symphony of traditions and daily practices that mimic life; yet it’s not life, it’s a motion across the musical scale. The sound of your steps as you leave the bed in the late morning hours, heading to the bathroom; the whistle of the electronic water heater as I prepare your coffee; the sounds of pain I make as I walk up the stairs to our room—they all join together with the endless sounds coming from across our old house. They create a life that we can feel within us even when we’re not paying attention to the noise.

I have grown attuned to this music, and now I cannot imagine my life without it. It’s a secret joy of mine to allow my mind to wander around, drawing pictures of your heavy white-haired eyebrows in my head as you look in the mirror for an old, beautiful self that you’ve lost. Even when I’m sitting in the garden with the dogs, I can see you trying to slowly take another step on the stairs, the fifth stair always creaking a bit; I have to find time to fix it.

Our garden is vast, with greedy trees and bushes growing around it like a bracelet surrounding a wrist. In the numbered sunny days of Vancouver, it turns green, with flowers eyeing each other, preparing for another mating season. During the rainy days of winter that last too long and bind us to the house, it gets muddy, with small pools of water gathering in its corners. The heavy rain adds to the symphony, producing a rhythm of endless drums when it hits the ponds around our garden.

Our house used to be white when we bought it twenty-something years ago. We painted it red back then. We thought it looked lively and sweet, and then decided to turn it green. The colour reminded you of your family’s home back in Damascus. Finally, as we got older, we abandoned the happy colours and resigned ourselves to a dark shade of grey for the walls, the same colour I see in your eyes in the early morning hours as you wake, asking for your medicine and your breakfast.

The wind used to hit the southern side of the house, opening windows and cracking doors. It freaked the dogs out and woke us up in the middle of the night. The wind whistled like an amused stranger catcalling us. It brought in the smells of English Bay and Sunset Beach. It carried the flavours of the doughnuts from the nearby Tim Hortons and made you desire them almost every morning.

We don’t feel the wind hitting the house anymore, taking away one of our symphony’s main instruments. Tall skyscrapers ganged up around our little two-storey home and surrounded it slowly but aggressively over the years.

You used to fill the house with paintings, mosaic pieces and traditional seating areas, like your own family home back in Damascus. You used to spend weeks moving furniture pieces around, then standing in a corner, silently making calculations in your head for all the possible social gatherings that we never held. You would wonder if your grandfather’s black and white framed photo should be centred on one wall or tucked away in a small corner of your den. You suggested a blue carpet for the living room, then replaced it with a dark yellow one, which you regretted days after you bought it. You used to work in the garden and enjoyed watering the plants.

You don’t wonder anymore. You don’t garden. You haven’t moved a single piece of furniture in five years. The living room has no carpet and your grandfather’s photo is collecting dust, where you left it in an abandoned corner of our storage room.

At night the sounds of our lives disappear, opening the air for sounds of the unknown, which escape through the windows into our home. At night you sleep and I keep awake, listening to their voices and trying to decode their messages. Will they tell me a story for you? Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t. Your rhythmic inhale and exhale keeps me awake, and I wonder. Are you dreaming of your own paradise?

When you were just a boy, you expected the world to be yours for the picking. You opened your heart with laughter and cracked jokes. You showed me an old video of yours, recorded on a camera borrowed from a wedding planner your father knew. You were standing there, listening silently to the beat of a reggae song that got too famous in Syria in the early nineties. You were wearing a white jacket and a red bowtie. You suddenly started to dance, unaware of the people around you, unhinged by the laughter of your father. You started imitating the movements of the dancers in the music video, swaying left and right to the song, repeating its chorus loudly. You moved your feet as fast as you could and shook your head to the beat.

That, you’ve told me, is your heaven. That was the time you were still yourself, before you escaped the reality of life and imprisoned your thoughts inside your skull. As you grew older, you left behind the laughter and the dancing and embraced a sarcastic sense of humour that you only share with yourself, and a desire for a personal space, and a need to be left alone to your thoughts.

Your inhale gets heavier and for a second, my heart jumps in fear. I finally see you opening your eyes. You smile to me. “Will I get to tell you the ending this time?” I ask while I pull you closer to my chest; you rest your tired brain, filled to the brim with medication, there on my chest. I hear the little crack my broken rib produces as it aches under the weight of your head. I ignore it like I have for the past sixty years. You hear the crack too.

“I don’t want to bother you,” you say, adjusting your head. “You never healed that broken rib of yours.”

I pull you closer. “Don’t worry about it. I rarely feel it anymore.” I scratch my chest right on the corner where my broken rib rests.

In my early twenties, I lived in Cairo for a while. I told you this story once, years ago, but I’ve never repeated it. I don’t enjoy telling old stories of broken ribs and painful experiences. They don’t feel like stories of mine; these are the stories of the other men who lived them instead of me. Every stage of my life feels like a story of a different man, each one a man I don’t know well. A man I don’t understand anymore.

This story is of a man who lived in Egypt in his early twenties. He was the one who escaped his family in Syria and moved to a country he only knew through mummy films and young adult books. Why did that man make those decisions? What made him ignore all the signs and walk down that empty, dark road on the outskirts of Cairo, alone and innocent?

That stranger man was outed as a homosexual to a group of Egyptian friends. You know how this story goes: he got a phone call one afternoon from one of these friends. He was asked to come to a mall, and he went there. In a food court, right next to the smelly meals of McDonalds, that stranger sat with his friends.

“We hear stories about you,” one of them said. He was a tall, dark-skinned man with a heavy moustache and the belly of Santa Claus. “We want you to know that we support you, we will carry you, we will stand behind you.”

“What are you? Are you a top or a bottom?” said Fady, who the stranger man had a crush on. “I mean, if you’re a top, just get married to a girl and do with her as you please.”

The stranger didn’t want to reply to their inquiries; he felt cheated and cornered. He wanted to leave the table and never look back. He wanted to escape into his own fantasies. Inside his head, he was holding Fady’s hands, and Fady understood, even welcomed his emotional advances. The two shared a kiss, a touch and a whisper.

The group, all eight of them, were still discussing the matter of this man’s sexual life; they were all attempting to agree on a plan to salvage what was left of his soul. “We might each be able to afford to contribute a small amount of money for him,” Fady said, referring to that man who used to be me. “And we can prepare him for marriage.”

The stranger man finally found a reaction within himself.

“I never asked for your approval or for your understanding,” he said. He spoke to them about the endless nights all of them had spent in his house, the many times all of them shared the same bed with him and spoke of love and loss as the wee hours of the night came to a close. He felt that all these moments, which he held dear, were becoming meaningless. “You slept next to me.” He pointed to Santa Claus, whose face was now red. “Did I touch you? Did I bother you? Did I even remotely make you feel uncomfortable?” Everyone was lost for words.

The stranger man escaped the table; he jumped the escalator and found himself standing in front of the cinema. He gazed at the posters and decided to watch V for Vendetta.

On his way into the cinema hall, he found himself starting a conversation with a clerk. The clerk was a handsome, dark-haired young man around his age. They exchanged short sentences as the man waited in the line for the door of the cinema hall to open. The stranger man wondered if they were flirting, and as the conversation continued, he realized that they were. “I’ve seen this movie a couple of times before,” the clerk said, playing with the small flashlight he carried in his hand. “It’s a great one.”

The clerk explained how the movie had touched him. “V is a lone wolf,” he said, gazing into the man’s features with his wide dark eyes. “He is abandoned by society and rejected by his peers simply for who he is.” By that time, the man only wanted to grab the clerk’s side, and dip him into a deep kiss.

“But he managed to change his society to accept him for who he is,” the clerk added softly. His lips were attractive, his skin was glowing with warmth. “It was an act of revolution.”

“I have no idea how they missed it,” the clerk whispered to the stranger, “but there are two women kissing in the movie and the censorship gods of Egypt didn’t remove it from their final cut.”

As the stranger walked through the hall toward his seat, the clerk followed him with his eyes; in the darkness of the cinema, deep between the scenes of the movie, the clerk slipped into the empty seat next to the stranger man. He whispered a quick hello and then sat there, watching the movie.

Moments passed, and the clerk’s hand found its way to touch the tips of the stranger’s fingers. The stranger man pulled the hand toward him and grabbed it with his own. The two hands clinched into each other as the two women on the screen shared a sweet kiss. Their fingers played a game of hide and seek while V and Evey danced to the beats of their own hearts at the start of the third act. Silently, the two of them heard V whisper, “A revolution without dancing is a revolution not worth having.”

As everyone started to leave the halls, and light returned, their hands unclenched. They looked at each other and smiled. “Can I have your phone number?” the clerk said shyly, and the stranger man smiled. They both shared their contact information as they felt blood streaming to their faces. They departed on the promise of a meeting.

The cold desert wind broke into the stranger’s clothes; he shivered as he walked the empty roads back home, unable to find a taxi. He felt safe, high on the promise of a date with a cute clerk with soft hands. He could hear footsteps behind him. The sounds of the night invited him to a slow dance. He walked, drunk with the cool breeze.

That was the night I was born from that stranger man’s body; I fractured from within him. That innocent man-child was alive as he left the cinema, and he was dead when I woke up in the hospital the next day with that dislocated shoulder, with those broken ribs.

When that stranger and I—still in one body—turned around, we saw them coming. They came fast. They were seven. Fady wasn’t among them. Their familiar faces were holding unfamiliar expressions. The first kick came right between the legs. “Khawal,” one of them said. “Faggot!”

The stranger man and I didn’t argue; we just stood there, trying to protect our face. There was a blow to the chest, followed by a sharp pain in the lungs. There was a kick to the knee that dropped us to the ground. Then the many kicks came. “I’m doing it for you,” Santa Claus said. “You should know who you truly are.”

The stranger’s hands were weakened. He couldn’t protect his face anymore. Slowly, they slipped to his sides. His chest took a kick from the sole of a shoe. He heard the crack echoing in his head, as his fractured rib gave up and broke completely. I heard it too.

His mind was racing, his thoughts interrupted. Their kicks mangled his insides every time they connected. He tried to take a deep breath. He tried to speak. The words died on his tongue. He tried to beg for forgiveness to a sin he didn’t believe in. He heard his own breaths. He gasped, but couldn’t get the air inside his body. He felt suffocated. He wished for them to stop. He wished for them to hear the cracks of his bones. He wished for mercy.

In his mind, he saw their smiling faces when they gathered in his little apartment on weekends; someone would bring the shisha, another would buy enough kushari or sunflower seeds for everyone to enjoy. They played Red Alert together, sometimes online, sometimes on two computers they assembled in his apartment. He would make them tea. They would borrow his books and read his short stories.

His pain started to fade away from his body. He couldn’t feel it anymore. I became his hurt locker; I became his vessel of sorrow. He started to lose his grip on reality. While I remained behind, taking blows, he slipped into his fantasies.

In his mind, he would call and the clerk would pick up the phone. They would meet again for a coffee somewhere over by the banks of the Nile. He would buy the clerk a rose from a flower girl wearing a dirty scarf. The clerk would take it and press it inside a graphic novel he had bought weeks before. The book would forever smell of flowers, and the rose would become immortal like a rose made of glass.

Every weekend they would go together to the movies and watch a comedy or a drama. They would argue over superhero movies and hold hands in the darkness of the cinema. When they went home, they would kiss goodnight. They would grow old together and one day, while asleep in his lover’s arms, in a bedroom covered in movie posters, he would peacefully slip into his final slumber.

With a final kick that landed on his face, he returned to the dark alleyway. He coughed blood, spat it to the side. “Bas,” he begged, “enough, please.” His cracked rib must have punctured his lung; I felt it root itself there. It grew like a tree within his lung, with parched branches that carried no leaves. It reached the corner of his heart and scratched the inside of his ribcage. He was finally dying. “Bas,” he whispered, but his gasp came out as a hiss, coated with blood.

That night was my first encounter with Death.

He came swiftly, a smile on his skeleton face. He waved his fingers and the world stopped; a drop of blood from the corner of my eye froze on my face, like a red tear that I didn’t cry. The faces became masks of anger; the feet were suspended millimetres from my body. “You can let go now,” Death said. “Just announce yourself gone, and you will be gone.”

Death was wearing a black cartoonish hood; his fingers, touching my face softly, were sticks of ice. He showed me everything that night: he showed me the future I would have, the stories I would tell and the men I would meet. He showed me you, my love, and I saw you. “This is your life,” he told me. “You will be sitting at the bedside of your loved one as he dies, and slowly, you will tell him stories, trying to keep him away from my final touch.”

He asked me, while darkness was coming over me, if I was ready to let all of this go and disappear with him into the unknown. I wasn’t. “You’re not telling the stories to keep him alive,” he told me. “You are telling the stories because you don’t want to face life without him. It will be a selfish, sad act of self-preservation.”

Scheherazade did not love the sultan. She didn’t want to fix him. She murmured her stories to keep her neck away from the hands of the swordsman.

The world around me was dark and I only saw the light in Death’s eyes. I reached with my palm, and I grabbed Death’s face in my hands. I printed a bloody kiss on his white teeth and begged him to let me stay.

That was when Death skinned me from that innocent man. It was a painful moment; it felt as if part of my soul were being removed. Death smiled at me, and from within me, he took a ghostly figure, a man-child who I used to be, and now he is a stranger to me.

That man visits me sometimes, while I’m lying here in bed with you. He reminds me of stories long gone. He whispers poems in my ear as I wait for you to wake up so I’ll know you’re still alive.

“Tell me a story,” you say now. Death peeks his head from behind the cracked door; within his robes, I see that stranger man. He looks happy. He has poured his pain into me and left this world for an innocent heaven. His pain within me cannot be silenced. It rises every now and again. It becomes louder within my own bones. It feels like the scream of a child abandoned by his mother. Sometimes it echoes in my mind. It slams against my broken ribs and bounces against my dislocated shoulder. It pulls me away from you and slips me into dark places I don’t like, yet I keep it to myself.

I smile to you, my love, and I start telling you a story. “Once upon a time, a man told his lover a story called ‘The Most Beautiful Suicide,’ about a woman called Evelyn McHale.”

Evelyn McHale was long gone before she even hit the car. In her calm descent, falling from the eighty-sixth floor of the Empire State Building, her soul departed from her body, swiftly moving upwards, following her white scarf—the one she dropped off the edge of the building before she jumped.

I guess ghosts haunt in flocks. As I tell you the story of Evelyn, another ghost escapes the grasp of Death. She stands in the corner of our bedroom, eavesdropping on my story about a woman who, like her, abandoned the world.

I know the smell of her clothes; I know the deep look in her eyes. The ghost of my mother stands there silently. I hear her voice echoing from under the bed, hiding there like a monster. “I carried you for nine months within my body,” the voice repeats, yet the ghost remains still. “You’re a part of me.”

I was born in Damascus, a lonely child. I was called evil-eyed since even before the day I was born. On one of her good days, my mother told me that when she felt my first kick, an old maiden aunt of mine touched her belly. “He will grow and be a strong boy,” she said, her eyes sparkling with green envy. “You should take good care of him.” Since that day, my mother’s final months of pregnancy were troubled. When I was born, her milk was dry and salty. I grow up weak, easily picked on, lonely.

She looks at me with accusing eyes and I shiver. I remember you far too well, mother. You steal me away from my listening lover, away from my bed, and you throw me into the icy hole of memory. I see you sitting there in the corner of our dusty living room, waiting for my return from school, holding your knitting kit and working on a blue and yellow winter sweater. The sweater is ugly as fuck. Yet, I will have to wear it. The living room is dimly lit, the dust is everywhere and the TV is playing some nonsense Syrian soap opera. I hate the dust, I hate the soap opera, I hate the sweater and most of all, I hate you.

The air has its thickness; the wooden-framed windows haven’t been opened in months and I feel suffocated the moment I walk in the door, carrying my heavy school bag. You look at me from afar, you see the darkness behind my eyes and you know how much I’m afraid of you. You start smiling; your smile cracks into a laugh, as if you’re enjoying all the fear you’re pouring into my insides. Your laugh echoes throughout the house. It hits the schoolbooks in my room, my old tapes and the photos I hide from you.

“Hello, mother,” I tell you.

“Fuck you!” you say.

She didn’t hear the loud noise her body made when it hit the Cadillac limousine parked in front of the building; she didn’t see the people gathering around her dead body. She didn’t see herself, arranged in her usual elegant demeanour, her legs crossed at the ankles, her pearls neatly placed around her neck, her white gloves clean and sparkling. She didn’t feel the metal of the car, folded around her like a cloud in a child’s imagination; she didn’t mourn the loss of her high heels, gone midway through her flight.

Like a green moray eel, you sneak into my room in the middle of the night. Your clothes are dishevelled. There is no elegance to your love. One hand twists the doorknob slowly, while the other holds onto a kitchen knife. My trained senses wake me up, my eyes adjust to the dark in a second and I see you. You’re standing there on top of me, like a statue of poison and piss.

“Your eyes glow in the dark like a demon,” you tell me and I jump out of bed, pushing you away. You fall down, taking with you two shelves of my books, my only friends in the world, and I dive for an escape. Barefoot and in my underwear, I rush to the door.

“Come back here, you little shit!” I jump down the staircase three steps at a time. My fourteen-year-old heart is pumping blood across my young body. My muscles tense in fear, and tears on my face feel like rivers. I’m fearful, scared. You’re a goddess in your child’s eyes and a goddess is capable of anything. You’re a dictator bathing in my blood, and I’m weak, powerless and incapable of defending myself in the face of your knife stabs.

I can still hear your noise as you roam the house like a tiger in a cage, roaring with your loneliness. I rush in front of the closed shops, heading to my favourite hiding place behind the dumpsters at the corner of the streets, where a public staircase protects me from the eyes of passersby and the cold wind of the night. I pass the time counting cars and stars, waiting for your latest episode to be over.

Tucked away there, I break into a loud cry. I feel like I’m locked in a freefall, pushed from an edge into a hungry abyss. You’re a goddess, and I’m betrayed by my faith. Your heart was supposed to produce love for your children, the way your breasts were supposed to produce milk for them.

Between the buildings on both sides of our narrow street, leaning on each other like old friends, I must have fallen asleep. It wouldn’t have been the first time. In the morning, I gather myself and walk back home, avoiding the eyes of curious neighbours and shop owners. I bring my tired body up the stairs. I eavesdrop at our gate, hoping to hear your snores filling up the house. When I’m assured you’re fast asleep, I slip through the door to my bedroom.

I remind your ghost, as you stand there in the corner of my bedroom, stealing my fleeting moments and final nights with my lover, that it wasn’t the last time I took that walk of shame.

Like a moon rising from the darkness she appears in front of me, in a photo taken four minutes after she met her end. I try to ignore Evelyn McHale, but she is haunting me. She lies there like the daughter of a goddess who sacrificed herself for the sins of others. “Tell my father,” she said in her suicide note, “I have too many of my mother’s tendencies.” She feared for her lover and her own offspring, and she atoned with a blood sacrifice. She calls my name, wondering if I needed a hug, a kiss or a bedtime story. Her closed eyelids, her hair, her dress, which I assume is the colour of red wine, are all printed on my brain cells; they glow, leaving a negative of her image in the back of my mind.

Like the men gathering around the dead body of McHale, I’m alert. I can smell the smoke coming from outside my room in the late morning hours. What now? I ask myself and I open the door, only fearing that my well-studied exit route might be blocked with fire. I slowly walk into the house, sniffing air through my nose, trying to find the direction of the fire. I go to the kitchen. Maybe you forgot another failed attempt at cooking in the oven. The kitchen is deserted, the sink is filled to the brim with eggshells I left there alongside dirty dishes from an endless number of omelettes I made for myself. A rotten banana cluster is in the corner with flies roaming around it, and the potatoes in the plastic basket grew long, twisty roots. The smell of burning oil fills the ceiling. The fridge’s door is forgotten open, but the fridge is empty.

My heart beats faster. I wonder if you’re burning the front door. The thought of death suffocates me like ash.

The smoke is coming from the balcony. You stand in a corner, in front of you a huge tank; I see flames of fire reaching out from within it. The flames reflect in your eyes; they never blink. On your face, a smile grows; you’re amused, like a child repeatedly hitting his sister’s doll on the wall, smashing its face in.

I decide to investigate. I move closer. I take a step toward you and cough loudly, hoping to break you out of your trance. You don’t recognize my existence. I finally cross the door and I join you on the dusty old balcony. I always imagined this balcony as an escape; I wished it was wide enough for me to build a swing.

Deep within the fire, dozens of photos are burning slowly. I gasp as I realize that those are my photos: photos I took at camp when I was twelve; a school photo I looked utterly sick in; a photo of you, a rose in your hair, the sea glowing behind you; a photo of me and my cousins in our Eid clothes; a photo of me laughing my heart out while playing a game of jump rope with another boy. My little face in that photo is burning. The fire is eating the sides of the photo, burning the rope, destroying the features of the other boy, reaching my body, burning off my arms, my ears, my hair, my forehead and my eyes, and finally reaching my laughing mouth, hushing a painful scream.

Across the narrow street, from the balcony of an old building, a neighbour is curiously gazing at us as we stand quietly for an hour. The fire takes you into a land within your own imagination; your eyes are following its flames. There goes #ThrowBackThursday and the endearing photos of my childhood.

Fuck it, I’m not giving you a reason to slap me across the face. I will remain silent; you can burn down the house for all I care. At least the smoke masked the rotten smell of our kitchen.

The neighbour, however, isn’t as wise as me. “Is there a problem?” he asks from his balcony across the street. Two people look up from the street and wonder. You don’t respond. You calmly go back inside and pick a book from my room—the Arabic translation of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I’m happy that I’ve already read it.

You aim and throw the book across the street; your weak hand doesn’t help you, but the theatrical act scares the neighbour into minding his own business. “Fuck off,” you whisper to yourself. The book hits the building across two floors down, and then continues its descent to the street, waving its pages like a frightened bird.

“All photos are haram, they are all sinful,” you say. “They are gateways to hell and will bring ghosts and demons across.”

I stare for a second at my book, all the way down in the street. A man steps on it, another kicks it, until it disappears.

Jumping off the Empire State Building immortalized her forever. She jumped to be forgotten. Her final portrait tells only of her struggle, her relief to end a longing to belong. She looks as if she has been walking a long walk in a jungle of hay and decided to rest on the grass, kicking her high heels away and enjoying the sunlight with closed eyes, touching her chin lightly with a daisy she picked on her long journey. Except the grass is a bed of metal, the body is dead and the daisy is a sharp piece of glass.

When did I decide to run away? I honestly can’t remember. It came like an unexpected spring after a long winter. The idea got hotter like the heat of the sun in April, breaking through the storms of your screams. It shone into the dark haze of your abandonment and isolation.

That final moment, with its urgency, will forever travel around with me. You tell me that you’re leaving for a walk. You go for a long walk every day; you disappear for hours. No one knows where, and no one seems to care.

You put on your makeup, bright green mists of colour across your eyes, a touch of red on the lips and a white scarf, and you walk down the stairs step by step, your high heels knocking on the floor, creating a hypnotic rhythm. As soon as it disappears, I rush to the balcony; I see you walking down the road, your famous blue jacket, your favourite stockings, your white handbag. My nose is filled with the smell of my burned memories, their ashes still resting in the bottom of that barrel. You take your steady steps down our street and you’re gone. My sun is shining. I’m leaving.

My books are disposable. I only keep my favourite. My clothes are not many; I only pick the ones without a stain of blood or a stain of memory. The bag, which used to be my school bag, is filling up fast with my stuff. In my pocket, there is money. My shoes are waiting for me by the door.

I take a final look at my room with its single bed, the blue mattress, my wooden windows, my shelves of books—some broken, some intact. The small white sofa and the small fireplace. I say my goodbyes, and I never see them again.

As a final joke, I close the outside door behind me and I turn the key, breaking it inside the lock. I smile wickedly.

Ten years have passed since I saw you last, mother. I avoided you at every corner of my life; my escape continues for what seems to be an eternity. How to escape your own DNA? How do you look back and think to yourself “fuck this shit!” and move on?

At the top of three steps leading to a small restaurant in a corner of Damascus, I was reunited with you on an early spring day in the late 2000s. I wondered if you would walk down to me, or if I should come up to you. Conscious of my surroundings like a street cat, in the back of my head, I couldn’t stop myself from studying the area around me looking for possible escape routes.

You hugged me and I shivered. You asked me about me, about my journeys around the world. You smiled, you laughed and you seemed calm and balanced. I felt claustrophobic, and I longed for a breath of air. You spoke about how you felt lonely. Alone you would sit in your old house, after you drove away everyone around you. Cornered in a war zone you didn’t understand and left to fend for yourself.

I don’t know what bothered me more: the fact that you seemed to assume you were still my problem, or the fact that you seemed to have forgotten every moment you abandoned me, every slap on the face I got when I asked for dinner. I felt a shake murmuring through my body, like the whisper of a child in my ear. I felt weak in the knees, as if I were still a young boy, crying for your attention, dying for your approval, hiding behind dumpsters.

An hour later I said my goodbyes and you asked me where I would go next. I answered, honestly, “I don’t know.”

Did she scream? I ask myself. The story I tell my lover feels weak, unprepared. My fantasy stretches through time and place; I see Evelyn falling off the Empire State Building. In my mind’s eyes she doesn’t. She relaxes her body, allowing the wind to carry her, closes her eyes and moves on to the next life. Did she scream? I doubt it. But there must have been a second of a gasp. That moment of uncertainty before she accepted the coming death, a moment when all the logic in the world crumbled and she produced sounds like a squeezed lemon, bitter, ugly sounds, before she calmed down, allowing the wind to carry her softly. Only then the pain stopped, the heart stopped pumping and death came, quick, inviting and final.

For twenty years, my mother was stuck in the first moments of the most beautiful suicide, insanely trying to change the outcome of her decisions, screaming, hitting the air with her fists, angry at the world. Now, as she accepts her unchangeable fate, she clings to the memory of an elegance that was never hers; she adjusts herself, allowing her final portrait to show what she considers her real self: pearls around her neck, perfect hairdo, disregarded high heels and the smile of acceptance on her face.

But I won’t be part of your descent, mother. I’ll meet you at the limousine.

“I feel sad,” you tell me as I finish the story. The sounds around us are filling the air again; it’s a new morning at last. Once more, I managed to keep you alive for another night; I can now sleep in peace. This Scheherazade needs her beauty sleep.

“I’m sorry I made you feel sad,” I respond as I click a button and the curtains slowly close, like the curtains of an old theatre after a well-acted play.

“This story is about your mother, isn’t it.” You state the question like a fact; you don’t wait for a response and you turn your body around, giving me your back. On your back, I see the small burnt bird tattoo.

I smile and I pull the covers toward me. “You’re always a puller,” I say, “leaving me with no covers.”

As I slowly allow my body to welcome the smaller death, enjoying the last waking moments of the day before I let myself depart this world and enter the world of the dreams, I whisper a song to Death, still standing at the door. He smiles at me; under his robes I see her face. She looks at me, sometimes with guilty eyes. Sometimes she blames me for abandoning her back in Damascus as I travelled with you across the world.

“Give me some space,” Death tells me, as he makes his entrance slowly into the room. I hear him, but you don’t. I see him walking there toward our bed, but you’re blinded to his presence. He mirrors your movements sometimes, mocks you while you look him straight in the eyes but can’t see him. He smiles at me like an old friend; he is my own private torturer. He is my constant reminder that you’re soon to be gone. I welcome him to our bed. Like every night since I can remember, he joins us, sleeping in between you and me.