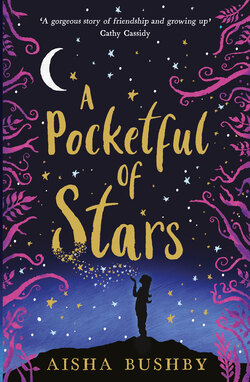

Читать книгу A Pocketful of Stars - Aisha Bushby - Страница 11

Оглавление

The next day at school everything’s a little strange. The teachers keep talking to me in really high-pitched voices, eyes creased with sympathy. It’s the way strangers talk to Lady in the street. Usually she wees on them in response. She does that a lot when people are nice to her.

As I was getting ready to leave Maths for lunch Ms Belgrave called me over, handed me a pack of sweets and winked, like it was a secret. Except, instead of winking she kind of just twitched her eye. I didn’t wee on her, the way Lady would, I just took the sweets and said thank you.

I suppose Dad will have told the teachers about Mum, but that doesn’t explain why everyone else is staring at me. I keep checking to see if I have toilet roll on my shoe or a giant spot in the middle of my nose.

‘What do you think, Saff?’ Elle asks halfway through lunch.

I turn to her, eyes wide. I realize I haven’t been listening. I’d been thinking about the strange dream I had at the hospital yesterday.

Izzy saves me. ‘I think he’s cool,’ she says.

That’s when I realize they’re talking about Matty Chung, Elle’s latest crush. I glance over at him, where he sits with his best friends Jonnie and David.

I don’t know how to respond because I don’t really think anything of him, or any boys, for that matter.

I remember when we were in Year Seven and no one else talked to us. Sounds weird, but I preferred it. We used to have a sleepover at Elle’s house every Friday night. We would do our homework first while Elle’s mum baked. It was usually cookies or a cake that she would let us have as a treat before dinner. Afterwards we always watched a film and then stayed up late chatting or playing silly games in bed when we were supposed to be sleeping.

But then Year Eight happened, and we made more friends, and now everyone wants to hang out at Maccies after school or go to the cinema with boys. Everything’s changing so quickly that it feels like my world is crumbling, just like in the dream. Like everything I’ve ever known is made of sand; one big wave could wash it away into the ocean.

‘Saff !’ Elle whispers furiously. ‘Don’t stare at him. He’ll know we’re talking about him.’

‘Sorry.’ I smile sheepishly and turn back to my lasagne.

‘What’s the latest anyway?’ Elle asks. ‘How’s your mum?’

Three pairs of eyes turn to me just then, and I want to shrink away from their sympathy, hide from their curiosity.

‘I don’t really know,’ I admit, playing with my food. ‘Mum’s in a coma still. Apparently she had some sort of stroke. There’s a fancy name for it, but I can’t really remember it now.’

What I do know is that being in a coma is kind of like you’re asleep, except you can’t be woken up by loud noises or dogs licking your face in the morning.

Often the patient – which is how they keep referring to Mum – wakes up after a few weeks, once their body has recovered from the trauma. I don’t think about the other outcome, which is that some patients never wake up.

The doctors asked Dad and me if Mum had any symptoms in the weeks leading up to the stroke. The main symptom, they explained, was a headache about a week or two before.

My heart dropped when they said that, because Mum had complained about a headache during our argument. And then I’d . . .

I didn’t tell the doctors about it, though, because that would mean I would have to tell them about the argument, and I don’t know if I could bear to find out that it was all my fault.

‘She had an operation on the first night, so now all we can do is . . . wait,’ I finish lamely.

Waiting feels so . . . wrong. I want to do something, to help. But instead I just have to live life like normal.

Dad said it was important to maintain my routine, whatever that means, and carry on with school and friends. But why pretend everything’s fine when it’s all wrong, wrong, wrong?

Suddenly tears well up in my eyes.

‘D-does anyone want some sweets?’ I ask to avoid the embarrassment of crying. ‘Ms Belgrave gave them to me,’ I add, accidentally spilling the contents all over the table.

‘Oh, Saff !’ Elle says, grabbing my hand. Izzy goes to get a tissue, while Abir strokes my shoulder. ‘We’re here for you. Anything you need . . .’

I nod. ‘Thank you.’ I smile back at them, even though I want to keep crying.

I try to focus on doing something, instead of sitting here and moping. That’s when I get an idea.

‘Actually . . .’ I say. ‘There is something you could do for me . . .’

A little while later I leave school just before the bell rings for the end of lunch. I asked Elle and the others to let our form tutor know I’ve gone home.

Except that’s not really where I’m going.

With shaking hands I put the key in the lock and let myself inside. My first thought is that it’s really quiet. Usually the TV is on, or some music. I switch on the lights, take off my coat, and turn on the TV for background noise. My second thought is that it smells like her – Mum’s flat.

It’s a full minute, maybe more, before I can bear to step inside any further. It’s as if I’m glued to the door, paralysed, like a wizard has trapped me in a snare. My blood is pumping around my body too quickly and I feel my limbs tingling, too heavy to lift. I crouch down at the threshold for a moment until the feeling passes.

The living room’s a bit of a mess. The house phone is on the floor. Dad said Mum called the ambulance herself. She could tell something was happening to her. The coffee table has been shoved aside – that must have been the paramedics. Then there’s papers scattered all over, and a big beige stain has ruined the white carpet. Coffee. Mum never drank anything else. Her mug – the posh floral one I got her for her birthday – stands upright on the table.

The papers look like a report from one of Mum’s cases. I gather them up, careful to make sure they’re stacked in order. If Mum gets home she’ll . . .

When . . . I think instead. Because Mum’s going to be OK. I know she is.

There’s a bunch of post by the door that must’ve been delivered after Mum went into hospital: some letters and a delivery card. I put them on the table too.

Next, I make my way to the kitchen.

I almost can’t go inside when I see the table set for two, and the remnants of the meal Mum was cooking laid out on the counter. My heart lurches. I should’ve been there. She thought I was still going to come over. Or maybe she hoped.

Some of it has been put away, like someone’s tried to tidy after her, but they didn’t do it properly, and the smell of herbs still lingers.

Mum’s always been a messy cook; it drove Dad up the wall. He usually did all the cooking, and he could never quite handle it whenever she insisted that it was her turn. He would hover, cleaning up behind her. Dad is all about order. Mum was . . . is . . . free.

I decide to finish the tidying. When I’m done and everything looks normal again I stand and look around, feeling a little strange, like I’m trespassing.

Like in the dream.

What have I come here to do?

I think back to the man at the hospital with his tartan blanket and his books, and then stare around Mum’s flat. What shall I take in for her?

I think of the mug on the table, but she can’t exactly use it, can she?

In the end I settle for a throw she always keeps on the sofa, covered in yellow flowers, and a worn-out cushion that’s shaped like a fox. That’ll make her hospital room prettier, won’t it?

I decide to try her bedroom next. As soon as I walk in her signature perfume envelops me. It’s musky: some sort of wood, rose and maybe orange? It smells like comfort and childhood and home. But I daren’t touch it. It’s too special.

Instead I reach for her hand cream. Mum was always moisturizing her hands. She would offer me some every time, but I always refused.

‘They make my fingers greasy,’ I once moaned.

‘Oh, don’t be so silly!’ she said, chasing me around the room. Eventually Mum caught me and slathered my palms in lotion. ‘You’ll thank me when you’re my age and have the hands of a toddler.’

‘That sounds so weird,’ I said, grinning. At the time I imagined grown-up Mum walking around with tiny hands.

I still remember the way Mum laughed at that. Each note of it floated up, up, up, filling the room with joy, like birds singing on the first day of spring.

I put a pea-sized amount of hand cream on my palms, and rub it in carefully, the way Mum always does.

As I leave Mum’s room I notice a photo by her bed. It’s of my grandmother standing in front of a great big house. I’ve never met her, only seen photos. She died before I was born, but Mum used to say her soul went into my body, so it’s like she’s still here. Toddler Mum stands next to my grandmother, clinging to her skirt.

I’m so focused on my mother and grandmother that I barely notice the house. But when I do I almost gasp. Apart from the silver branches it looks exactly like the one in . . .

‘My dream,’ I say aloud.