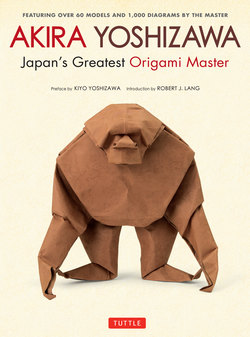

Читать книгу Akira Yoshizawa, Japan's Greatest Origami Master - Akira Yoshizawa - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION BY ROBERT J. LANG

Akira Yoshizawa:

The Father of Modern Origami

Akira Yoshizawa is considered by many to be the father of the modern origami movement. At first glance, one might wonder why this would be so. After all, origami is an ancient art within Japan, and we find examples of paper-folding in many other ancient cultures, even in the Americas over a thousand years ago. Yoshizawa-sensei was certainly not the only Japanese artist creating original designs in the mid-20th century. It is fair to say, however, that he was by far the most influential origami artist. By the end of the 20th century, origami had become a worldwide passion and an art of astounding diversity, with active societies and creative artists in many countries on nearly every continent. If, however, you trace the origami lineage of any given artist—who they learned from, who they were inspired by—while their roots may be manifold and diverse, the deepest roots lie within the Japanese folding art, and the majority of those roots pass through the work and inspiration of this man.

Robert J. Lang

PERSONAL REMINISCENCES

I first learned of Yoshizawa in my childhood via English-language origami books, which described him as the grand master of origami, showed a few of his simpler designs, but hinted at additional remarkable, unbelievable artworks whose instructions, infuriatingly, did not appear anywhere. Hints were there in the photos, though. His great opus, Origami dokuhon I, which I eventually acquired, showed folding instructions for a simple horse, but accompanied it with a photograph of an incredibly detailed and lifelike horse, along with a caption that said something along the lines of “with a little bit more folding, you can make something like this.” Throughout my own origami development, Yoshizawa was the semi-mythical, somewhat mysterious ideal to aspire to.

In 1988, I had the incredible good luck to meet him for the first time. He came to New York for the 10th anniversary celebration of the Friends of the Origami Center of America (FOCA, which was the American origami society whose predecessor, the Origami Center of America, was founded on the model of Yoshizawa’s International Origami Center). I had the opportunity to organize a panel discussion on origami diagramming standards. As here was the man who had invented origami diagramming, we leapt at the chance to invite him. He spoke for about 20 minutes on a wide range of topics, not just diagramming. In fact, what seemed to matter most to him was one’s mental attitude, one’s entire approach. He spoke of character, of natural qualities, of having one’s “spirit within [the artwork’s] folds.”

Yoshizawa at Origami USA’s panel discussion, 1988.

I had the chance to meet him again in 1992 when I was invited to address the Nippon Origami Association at their annual meeting in Japan. During that trip, my hosts arranged for me to meet several origami artists, including the great Yoshizawa, this time at his home and studio. This was not an easy thing to arrange, but through the skillful negotiations of my host and guide, Toshi Aoyagi, an audience was arranged, and presently I was ushered into the inner sanctum where Yoshizawa greeted me, grinning, and then proceeded to show me box after box, drawer after drawer of the most extraordinarily folded works I had ever seen.

And then, finally, I got a glimpse of what set him apart from other origami artists. He showed me the same figure, a nursing she-wolf, folded two different ways. The first was folded in what one might call a conventional style, that is, the way every other origami artist in the world would have folded it. It was not terribly complicated. It had all the right “parts” (head, legs, tail, etc.) but no more. And then he showed me the same design, folded his way. It was, indeed, the same basic design, but through a combination of dents, bumps, wrinkles and molding of the paper he had captured the subject fully. I could see not just the features of the animal, I could see its personality as well. He was not just controlling the folds of the paper, he was controlling every aspect of the paper. He was controlling what happened between the folds.

As is well known, throughout his life Yoshizawa struggled for support and recognition. By the mid-1990s, though, Yoshizawa’s place in the origami world was well established and he was visibly comfortable being around other folders. He knew he was the ‘elder statesman’ of origami. He did not have to worry about his legacy. And so he relaxed and enjoyed the accolades and invitations that came his way. In 1998, artist Eric Joisel organized what was then the largest international exhibition of origami ever held, in the Carrousel du Louvre, a commercial exhibition space across from the underground entrance of the Louvre proper, and Yoshizawa was one of the honored guests at this exhibition. He was joyous as he walked around the space, and positively sparkled at the attention from origami aficionados spanning multiple generations.

HIS LEGACY AND IMPACT ON ORIGAMI

Akira Yoshizawa almost single-handedly defined the 20th-century art of origami, and while his contributions were many, two in particular stand out to me.

Yoshizawa and a young fan.

First, he broke out of the largely static repertoire of traditional designs and established a culture of development of new figures and, with it, the never-ending quest to capture the inner spirit of the subject. This act essentially set the modern art of origami on its present course. Yes, there were others in Japan and elsewhere who sought to create new figures in the early part of the last century. But no one conveyed this approach to the world more effectively, in part, simply due to the value of publicity, but even more, because the works themselves displayed a beauty and life that lifted origami out of the realm of mere playthings and into a true art form.

His second, and perhaps more long-lasting contribution, was the code of instruction that he developed—the arrows, dotted and dashed lines that we now take for granted. Again, others had developed ways of expressing origami instruction, but Yoshizawa’s system was so clear and compelling that it and its derivatives have become the standard for the worldwide dissemination of origami. The use of distinct lines for mountain and valley folds—similar to that of Uchiyama—is, perhaps, the most striking element of his system, but I think that something else turned out to be equally important—the use of distinctive ‘action arrows’ to indicate out-of-plane motion. Prior to Yoshizawa, most origami diagrams were static from step to step. Only with Yoshizawa (and after) do we see the full flow and movement that takes one step to the next, all the way to the finished figure.

When I was a young folder, eager to make my mark, FOCA co-founder and origami artist Alice Gray told me about her encounter with Yoshizawa at which he showed her his cicada, and he remarked that it had taken him over 20 years to design! “Hmmph!” I thought. “I don’t need no 20 years to design a cicada!” And I sat down and designed one, which I became very proud of, so proud that I put it in my first book. But after a few years, I began to perceive its flaws: the body wasn’t quite right, the wings weren’t positioned properly, the legs looked too generic. So I set about to design another. “Now,” I thought, “I’ve got it right.” But presently that one, too, began to display weaknesses. And so another. And in a few years more, yet another. None ever hit the mark. In 2003, I attended a Japanese origami convention and during a visit to the city of Shizuoka during the cicada emergence season, I looked closely at the cicadas on the trees all around and realized once again the flaws in all that I had folded before, and set out once more. The result was a figure I titled “Shizuoka Cicada, opus 445.” Finally, I thought, I had nailed it. But, you know, when I looked at a calendar … it had been about 25 years since I first started working on this subject. So I overshot Yoshizawa by a couple of years, and I guess that 23 years is not too long to fold a cicada.

THE MAGIC OF THE CICADA

Yoshizawa’s Cicada illustrates yet another remarkable fact about the man. He published many books with hundreds of folding diagrams, and yet all of his published work only hinted at the sophisticated design techniques that he had developed in isolation, on his own. Today, the origami world has conceptual tools for design, with names like “circle packing,” “tree theory,” “molecules” and more. In the 1940s and 1950s, the most sophisticated concept to arise in the world of origami was the idea of gluing two bird bases together, and perhaps using a few cuts here and there to obtain some extra features. Yoshizawa learned origami within that design culture, but set himself a goal to create the most detailed and realistic forms from a single uncut sheet of paper, and to accomplish this he devised entirely new folded structures that would not be rediscovered by others until decades later. None show these innovations more clearly than his Cicada.

Yoshizawa’s Cicada was his pride and joy. Time and again, in interviews over the years, he cited it as his masterpiece. In fact, he completed it in 1959, having worked on it for over 23 years according to a 1970 interview. Now, it is unlikely that he worked on that specific design for that period of time. Rather, it took 23 years to develop the concepts that could be brought together to realize it. Those concepts would include the pattern of folds, the choice of paper and the understanding of how it would respond to manipulations, and the folding skill to persuade the paper to take on the folds specified by the pattern. All of those skills were necessary to realize the artwork, but the artwork began with a folding pattern, and the folding pattern for the Cicada was like nothing that had come before.

In the early 1950s, Yoshizawa began corresponding with Gershon Legman, an expatriate American living in France who had developed a passion for origami and its history. It was Legman who brought Yoshizawa to the attention of the world and who arranged for Yoshizawa’s first international exhibition in 1955. Yoshizawa and Legman developed a deep friendship, expressed through their correspondence, and in 1962, three years after his Cicada milestone, Yoshizawa shared with Legman that which he was so proud of—his Cicada and its construction, via a photograph of the model and its folding plan from his notebook.

Yoshizawa’s Cicada, folded, and the plan from his notebook.

In fact, the notebook contained descriptions of two designs—an adult cicada (above) and a juvenile (nymph, below). Both are folded from a 2 x 1 rectangle and each from the same base, which resembles a tiling of eight Bird Bases, shown here in my transcription of his pattern for the adult. The tiling shows a clear ancestry with one of Yoshizawa’s earlier complex designs, his Crab.

The Crab was folded from a “double-blintzed Frog Base,” to use the modern terminology. The base for his Cicada could be thought of as two such double-blintzed Frog Bases attached side by side.

Such a pattern, however, demands an entirely different folding approach from the traditional step-by-step designs. With this pattern, one must pre-crease all of the relevant creases, then bring them all together at once in an action now called a “collapse.” Astonishingly, Yoshizawa shared the details of this collapse with Legman in a series of photographs that showed precisely how this base came together.

A key aspect of the collapse was the the ‘tucking underneath’ of a portion of the paper at several places, indicated by the shaded regions on the collapse photographs and highlighted by Yoshizawa in his crease pattern by drawing explicit mountain fold lines—dash-dot-dot—on the otherwise unmarked crease patterns.

In the modern era of complex design, “collapses” are ubiquitous. Sixty or more years ago, however, they were all but unknown. The complexity of this base, and the necessity of constructing it via a collapse move, were part of Yoshizawa’s “secret sauce” for creating complex designs.

And yes, it was secret. Although he shared the design with Legman (perhaps flush with pride at its recent creation), he never published instructions for this type of work in any of his books (and, indeed, you will not find it or its kin within the present collection). We might well wonder why that was. Could it be that he wished to keep some of his methods a secret? Could it be that he felt that diagrams would not adequately convey what folds would need to be carried out? Perhaps he simply felt that the challenge of creating these folds would be so far beyond the skills of most readers that the diagramming effort would be unjustified. Alas, we will never know.

There is no question that further challenges would have awaited anyone who would seek to fold this design. In later years, Yoshizawa shared further details of the artwork, notably in a Kinokuniya-produced documentary, “The Forming Hands, Deity,” portions of which may be seen in the origami documentary “Between the Folds.” The videos revealed that there were tricks in the actual folding—unfolding and refolding of the wing flaps, unfolding revealed by the faint presence of crease lines on the wings, which do double duty as veination and are indicated in his plan by the absence of mountain fold line hints at the far right. Perhaps more remarkable, in the collapsed base the abdomen flap winds up above the wing flaps. In order to move it to lie below the wings, a maneuver is called for, which in modern parlance we know as a “closed sink,” once again a step that would not find widespread usage within the origami world until years later.

Yoshizawa’s plan for the Cicada.

The collapse of the Cicada base.

Yoshizawa’s Cicada, folded by the master.

Fold angles, collapse notation and base geometry can be conveyed by drawings and plans, but there are many things that cannot be conveyed. The delicate shape of a feature, the reverse-folds or crimps of the legs, the hollow rounding that forms the eyes—these are forms that rely upon the subtle interplay between the fingers and tools of the artist and the mechanical properties of the paper—its tensile behavior, how it accepts a fold and springs back or takes on a plastic deformation. The understanding of this relationship and its relation, in turn, to the vision of the artist is the thing that cannot be fully conveyed in diagrams or even in photographs of the finished work. But diagrams and plans can give a hint, photographs can suggest, and the totality of available information lets us experience, if only slightly, the view and philosophy of Yoshizawa.

The unfolded/ refolded base, showing the closed sink (dotted lines). Reconstruction and drawing by Robert J. Lang.

To Yoshizawa, the life in the folded form was paramount, and that, perhaps, is at the heart of why his work remains relevant and instructive. There was a 30-year period—the 1970s through the 1990s—that might be called the “Golden Age” of technical folding, when origami design tools were developed that allowed the realization of undreamed of forms of complexity. By and large, Yoshizawa remained outside of that development. And the separation was mutual. Within the technical community, the focus on technological development often ignored the development of living form. An origami subject was merely a problem to be solved. But since the turn of the century, there has been a renewed emphasis on the finished form. Technology is back in its proper place as a tool in the service of an artistic goal. Yoshizawa recognized the priority of the artistic form from the very beginning, and his books, demonstrations and exhibitions have always brought out this philosophy. His work remains an example of breathing life into the paper, as relevant for the bird-base-bird as for the 100-legged centipede or the timeless Cicada. He is now gone, but his work will continue to inspire and educate folders no matter how much or little experience they have. I used to think, somewhat foolishly, that with enough time and experience I could fold like Yoshizawa. Now, I hope that with enough time and experience I will simply be able to fully appreciate his extraordinary work.

Robert J. Lang