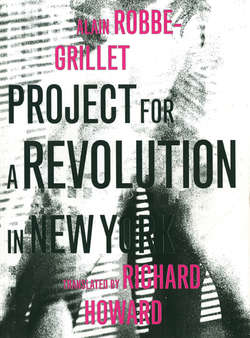

Читать книгу Project for a Revolution in New York - Alain Robbe-Grillet - Страница 6

Project for a Revolution

ОглавлениеThe first scene goes very fast. Evidently it has already been rehearsed several times: everyone knows his part by heart. Words and gestures follow each other in a relaxed, continuous manner, the links as imperceptible as the necessary elements of some properly lubricated machinery.

Then there is a gap, a blank space, a pause of indeterminate length during which nothing happens, not even the anticipation of what will come next.

And suddenly the action resumes, without warning, and the same scene occurs again … But which scene? I am closing the door behind me, a heavy wooden door with a tiny narrow oblong window near the top, its pane protected by a cast-iron grille (clumsily imitating wrought iron) which almost entirely covers it. The interlacing spirals, thickened by successive layers of black paint, are so close together, and there is so little light from the other side of the door, that nothing can be seen of what might or might not be inside.

The wood around the window is coated with a brownish varnish in which thin lines of a lighter color, lines which are the imitation of imaginary veins running through another substance considered more decorative, constitute parallel networks or networks of only slightly divergent curves outlining darker knots, round or oval or even triangular, a group of changing signs in which I have discerned human figures for a long time: a young woman lying on her left side and facing me, apparently naked since her nipples and pubic hair are discernible; her legs are bent, the left one more than the right, its knee pointing forward, on the floor; the right foot therefore crosses over the left one, the ankles are evidently bound together, just as the wrists are bound behind her back as usual, it would seem, for both arms disappear from view behind the upper part of the body: the left arm below the elbow and the right one just above it.

The face, tilted back, is framed by curling waves of very dark, luxuriant hair spread loose on the tiles. The features themselves are difficult to make out, as much because of the position of the head as because of a broad hank of hair slanting across the forehead, the line of the eyes, and one cheek: the only indisputable detail is the mouth, open in a long cry of suffering or terror. From the left part of the frame spreads a cone of harsh light, emanating from a lamp with a jointed arm whose base is clamped to the comer of a metal desk; the shaft of light has been carefully directed, as though for an interrogation, toward the harmonious curves of amber flesh lying on the floor.

Yet it cannot be an interrogation; the mouth, which has been wide open too long, must be distended by some kind of gag: for example, a piece of black lingerie stuffed between the lips. Besides, a scream, if the girl were screaming, would be audible even through the thick pane of the oblong window with its cast-iron grille.

But now a silver-haired man in a white doctor’s coat appears in the foreground from the right; he is seen from behind, so that only a hint of his face can be glimpsed in profile. He walks toward the bound girl whom he stares at for a moment, standing over her, his own body concealing a part of her legs. The captive must be unconscious, for she does not react to his approach; moreover, a closer look at the gag’s shape and arrangement just under the girl’s nose reveals that it is a wad of cloth soaked in ether which was necessary to overcome the resistance indicated by the disheveled hair.

The doctor bends forward, kneels down on one knee and begins to untie the cords binding her ankles. The girl’s body, docile now, lies prostrate as two steady hands part the knees, spreading the smooth brown thighs which glisten in the lamplight; but the upper part of the body does not lie flat because of the arms which remain bound together behind the back; the breasts, in this change of position, are merely easier to see: firm as two foam-rubber domes and splendidly proportioned, they are slightly paler than the rest of the body, their lovely sepia aureoles (which are not very large, for a half-caste girl) swelling a little around the nipples.

After getting up a moment and taking from the metal desk a sharp-pointed instrument about a foot long, the doctor has resumed his kneeling position, but a little farther to the right, so that his white coat now conceals the upper part of the girl’s thighs. The man’s hands, invisible for the moment, are performing some operation in the pubic region, though its exact nature is difficult to determine. Granted that the patient has been anesthetized, it can scarcely be a question, in any case, of some torture inflicted by a madman upon a victim chosen for her beauty alone. There remains the possibility of an artificial insemination effected by force (the object the surgeon is holding would then be a catheter) or of some other medical experiment of monstrous nature, performed of course without the subject’s consent.

What the person in the white coat was going to do to his captive will never be known, unfortunately, for at this moment the rear door opens quickly and a third figure appears: a tall man who stands motionless in the doorway. He is wearing a tuxedo and his face and head are entirely hidden by a thin soot-colored leather mask with only five openings: a slit for the mouth, two tiny round orifices for the nostrils and two larger ovals for the eyes. These remain fixed on the doctor, who slowly straightens up and begins backing toward the other door, while behind the masked figure appears another one: a short bald man in workman’s clothes with the strap of a toolbox over one shoulder, apparently a plumber, or an electrician, or a locksmith. The whole scene then goes very fast, still without variation.

It has obviously been rehearsed several times: everyone knows his part by heart. The gestures follow each other in a relaxed, continuous manner, the links as imperceptible as the necessary elements of some properly oiled machinery, when suddenly the light goes out. The only thing left in front of me is a dusty pane in which no more than a dim reflection of my own face can be made out, and the housefront behind me, between the interlacing spirals of the heavy black ironwork The surface of the wood around it is coated with a brownish varnish in which thin lines of a lighter color are supposed to represent the grain of the oak. The bolt falls into place with a muffled click, prolonged by a cavernous echo which spreads through the entire mass of the door, immediately dying out into complete silence.

I release the bronze doorknob shaped like a hand holding a skewer or stylus or slender dagger in its sheath, and I turn all the way around to face the street, about to descend the three imitation-stone steps between the threshold and the sidewalk, its asphalt glistening now after the rain, people hurrying by in hopes of reaching home before the next shower, before their delay (they must have waited somewhere a long while) causes alarm, before dinner time, before nightfall.

The click of the lock has set off the customary mechanism: I have forgotten my key inside and I can no longer open the door to get it back. This is not true, of course, but the image is still as powerful of the tiny steel key lying on the right-hand comer of the marble table top near the brass candlestick. So there must be a table in this dim vestibule.

It is a dark piece of furniture, its mahogany veneer in poor condition, which must date from the second half of the preceding century. On the dull black marble, the little key stands out with all the clarity of a primer illustration. Its flat, perfectly round ring lies only a couple of inches from the hexagonal base of the candlestick, etc., whose ornamental shaft (fillets, tori, cavettos, cymae, scotias, etc.) supports … etc. The yellow brass glistens in the dark, on the right side where a faint light filters through the grille covering the window in the door.

Above the table a large oblong mirror is hanging on the wall, tilted slightly forward. Its wooden frame, the gilding faded on the unidentifiable carved leaves, delimits a misty surface with the bluish depths of an aquarium, the central part occupied by the half-open library door and an uncertain, fragile, remote figure—it is Laura standing motionless on the other side of the threshold.

“You’re late,” she says. “I was beginning to worry.”

“I had to wait until the rain stopped.”

“Was it raining?”

“Yes, a long while.”

“Not here … And you’re not even wet.”

“No—because I waited.”

My hand releases the little key I had just set down on the marble when I glanced up toward the mirror. Memory of the contact with the already cooled metal (which my palm had warmed a moment before) still remains on the sensitive skin of my finger tips as I turn all the way around to face the street, immediately starting down the three imitation-stone steps leading from the door to the sidewalk. With a habitual gesture—futile, insistent, inevitable—I check to discover whether the little steel key is in the usual pocket where I have just slipped it. At this moment I notice the man in black—shiny raincoat with the collar turned up, hands in his pockets, soft felt hat low over his eyes—waiting on the opposite sidewalk.

Though he appears to be more concerned to avoid notice than the rain, his motionless figure immediately attracts attention among the people hurrying past after the shower. Moreover, they are less numerous now, and the man, feeling exposed, gradually draws back into the recess afforded by one housefront—that of number 789 A, whose stucco is painted bright blue.

This house has three stories, like all its neighbors (which constitute, about a yard closer to the curb, the general alignment of the street), but it must be of more recent construction, for it is the only one without a fire escape: a skeleton of black intersecting lines form superimpozed Z’s on the façade of each apartment building and end about ten feet from the ground. A thin removable ladder, usually raised, offers means to reach the sidewalk and permit escape from the fire blazing on the stairs inside.

A skillful burglar, or a murderer, could catch hold of the lowest rung, hoist himself up, and then simply climb the metal steps to the French window of any floor and enter the room he chooses, merely by breaking a single pane. At least this is what Laura imagines. The sound of the broken pane, whose splinters tinkle on the floor at the end of the corridor, has awakened her with a start.

She remains sitting bolt upright in her bed, motionless, holding her breath, not turning on the light in order to conceal her presence from the criminal who, having carefully thrust his hand between the sharp points of glass into the hole he has just poked with his revolver barrel or its heavier cross-hatched butt, or with the ivory handle of his switchblade, is now opening the window latch without making a sound. The harsh light of a nearby streetlamp casts its even larger shadow across the bright housefront, above the distorted shadow of the fire escape, whose various networks of parallel rays cross-hatch the whole surface of the building in a precise and complicated pattern.

When I open the bedroom door, I find Laura in this same posture of anxious expectation: sitting up in bed, leaning back against the bolster on both arms, head raised. The light from the corridor, where I have pressed the switch in passing, gleams in the dark room on the young woman’s blond hair, pale flesh, and nightgown. She must have been asleep, for the material of the nightgown is rumpled into countless creases.

“It’s you,” she says. “You’re so late. You frightened me.”

Standing on the threshold of the wide-open doorway, I answer that the meeting lasted longer than usual.

“Nothing new?” she asks.

“No,” I say, “nothing new.”

“Did you drop something on your way upstairs?”

“No. Why? And I walked as softly as I could … Did you hear anything special?”

“It sounded like broken glass on the tiles …”

“Maybe it was my keys, when I set them down on the marble.”

“Downstairs? No, it was much closer … Just at the end of the corridor.”

“No,” I say, “you were dreaming.”

I step into the room. Laura leans back, but she is not completely relaxed. She stares up at the ceiling, eyes wide, as if she were still hearing suspicious creaks, or as if she were trying to remember something. After a pause she asks, “What’s it like outside?”

“It’s a quiet night.”

Her transparent nightgown reveals the dark nipples of her breasts.

“I’d like to go out,” she says, without looking at me.

“You would? Where?”

“Nowhere. Out into the street …”

“At this time of night?”

“Yes.”

“You can’t.”

“Why not?”

“You can’t … It’s raining.”

I would rather not mention to her now the man in the black raincoat waiting in front of the house, on the sidewalk across the street. I start to close the door, but just at that moment, even before my hand has reached the edge of the door which I am about to push back, the light goes off in the corridor, and my silhouette, dark against the lighted doorway, immediately vanishes.

Made threatening perhaps by the raised arm, the extent of the movement, the muffled impact of the fist against the wood in the sudden darkness, the half-glimpsed image has alarmed the young woman, who utters a faint moan. She then hears, on the thick carpeting which covers the entire floor of the room, the heavy footsteps coming closer to her bed. She tries to scream, but a firm warm hand presses against her mouth, while she feels the sensation of a crushing mass which slides toward her and soon overwhelms her altogether.

With his other hand, the aggressor roughly crumples the nightgown as he pulls it up, in order to immobilize the supple body still trying to struggle, grasping the flesh itself. The young woman thinks of the door, which has remained wide open to the empty corridor. But she does not manage to articulate a single sound. And it is a husky, threatening voice which murmurs near her ear, “Keep still, you little fool, or I’ll hurt you.”

The man is much stronger than this frail young creature whose resistance is fruitless, trifling, and absurd. With a quick movement he has released her mouth to grab both wrists and pull them behind her, imprisoning them in one hand now in the hollow of her back, so that her hips are arched. And immediately, with the other hand and the help of his knees, he brutally parts her thighs which he then caresses more gently, as though to tame some wild animal. The young woman feels at the same time the contact of the rough material (is it a wool sweater?) which presses harder against her belly and breasts.

Her heart is pounding so loud that she has the sense it can be heard all through the house. With a slow, imperceptible movement, she shifts her shoulders and hips slightly, in order to make her fetters more comfortable and her position more accessible. She has given up the struggle.

“And then?”

Then she gradually calmed down. She stirred a little once again, apparently trying to release her aching arms, but without conviction, as though merely to make sure such a thing was impossible. She whispered two or three inaudible words and her head suddenly fell to one side; then she began moaning again, more softly; but not in terror—not only in terror, in any case. Her blond hair, whose curls are still glistening in the darkness, as if they were phosphorescent, has rolled to the other side and, drowning the invisible face, sweeps the bolster from right and left, alternately, faster and faster, until long successive spasms run through her entire body.

When she seemed dead, I released my grip. I undressed very fast and came back to her. Her flesh was warm and sweet, her limbs were quite limp, the joints obedient; she had become as malleable as a rag doll.

Again I had that impression of tremendous fatigue which I had already experienced on my way upstairs a moment before. Laura fell asleep at once in my arms.

“Why is she so nervous? You know that means an extra danger—for no reason.”

“No,” I say, “she doesn’t seem abnormally nervous … After all, she’s very young … But she’ll be all right. We’re going through a rather hard time.”

Then I tell him about the man in the black raincoat keeping watch on my door. He asks me if I’m sure I’m the person being watched. I answer no—I don’t think it’s me, in fact. Then he asks me, after a pause, if there’s someone else to be shadowed in the neighborhood. I answer that I wouldn’t know, but that there could be someone without my having any idea of it.

Tonight, when I left, the man was in his usual place, still in the same clothes and the same position: his hands deep in his raincoat pockets, his feet wide apart. There was no one near him, now, and his entire attitude, so assertive in his clothes—like a man on sentry duty—was so completely lacking in discretion that I wondered if he was really trying to avoid notice.

I had scarcely closed the door behind me when I saw the two policemen coming toward us. They were wearing the flat caps of the tactical police, the front edge very high, with the shield beneath and a broad shiny visor. They were walking in step, as though on patrol, right down the middle of the street. My first impulse was to reopen my door and get back inside until the danger was past, observing from behind the little grille the sequence of events. But then I thought that it was absurd to hide so obviously. Moreover, the gesture I made toward the key in my pocket could only be that belated mechanical precaution I have already mentioned.

I calmly walked down the three stone steps. The man in the raincoat had not yet noticed—apparently—the presence of the tactical police, which seemed strange to me. Though they were still about two blocks away, you could hear the regular noise of their boots on the pavement quite distinctly. There was not one car in the street, which was deserted except for these four people: the two policemen, the motionless man, and myself.

Hesitating a second between the two possible directions, I thought first that it would be better to take the same direction as the policemen and to turn at the first intersection, before they could have seen my fact at close range. As a matter of fact it is very doubtful that they would have marched any faster, without a specific reason, in order to catch up with me. But after three steps in that direction, I decided that it would be better to face the ordeal directly, rather than to draw attention to myself by behavior which might seem suspicious. So I turned around in order to walk along the housefronts in the other direction, toward the policemen who were continuing their steady, straight march. On the opposite sidewalk, the man in the felt hat was staring at me calmly, as though with complete indifference: because there was nothing else to look at.

I walked on, looking straight ahead of me. The two policemen had no particular character: they were wearing the usual navy-blue jacket and leather belt and shoulder strap, with the pistol holster on one hip. They were of the same height—quite tall—and had rather similar faces: frozen, watchful, vacant. As I passed them, I did not turn my head toward them.

But, a few yards farther on, I wanted to know how the meeting with the other man would turn out, and I glanced back. The man in the black raincoat had finally noticed the policemen (probably when they were between him and me, in the line of his gaze, which was still fixed on me), and he made, just at that moment, a gesture with his right hand toward the turned-down brim of his hat …

There wasn’t even time for me to wonder about the meaning of this gesture. The two policemen, quite unpredictably, with one accord turned around to stare at me, freezing me where I stood.

I can’t say what they did next, for I immediately went on walking, with an instinctive about-face whose abruptness I immediately regretted. Moreover, hadn’t my entire behavior since the beginning of the scene given me away: a hesitation (and doubtless a movement of withdrawal) on the threshold upon noticing the policemen, then an unaccountable change of direction which betrayed the initial intention of running away, finally an excessive stiffness at the moment of passing the patrol, whereas it would have been more natural to glance as though by chance at the two men, especially if I was to turn around to look at them subsequently as they walked away from me. All of which, obviously, justified their suspicions and their desire to see what this individual was up to behind their backs.

But what was the relation between this understandable suspicion and the gesture made by the other man? That almost looked like a tiny salute: the hand, which till then had never left the raincoat pocket, suddenly appearing and rising casually to the indented brim of the soft hat. It is difficult in any case to suppose that it was the intention of this placid sentry to lower the felt any farther over his eyes in order to conceal his face from the policemen altogether … Instead, doesn’t the hand emerging from the pocket and slowly rising point to the man walking away, wanted by the inspectors for several days and whose suspicious behavior has yet again aggravated the already heavy charges weighing upon him?

However, he continues on his way nonetheless, walking faster in fact, while trying not to let this be too apparent to the three witnesses behind him: in front of the building painted bright blue, the two policemen are still frozen like statues, their expressionless gaze fixed on this receding figure, soon tiny at the end of the long straight street, while the gloved hand of the man in black, completing a slow trajectory, has just come to rest against the far edge of the felt hat.

Over there, as if he imagined he was henceforth out of sight, the suspect person begins going down the invisible staircase of a subway entrance which is in front of him, level with the ground, thereby losing successively his legs, his torso and his arms, his shoulders, his neck, his head.

Laura, behind the window corresponding to the third-floor corridor, at the very top of the fire escape, looks down at the long street, at this hour quite abandoned, thus making the three disturbing presences all the more remarkable. The man in black whom she has already noticed the last few days (how many?) is at his post, as she suspected he would be, in his usual shiny raincoat. But two policemen in flat caps, wearing high boots and pistol holsters, walking side by side down the middle of the pavement, have also stopped now a few steps from the first observer—who gestures to them with one hand—and turn around in unison to look at what he is pointing at: the window where Laura is standing.

She quickly steps back, quickly enough for neither the policemen nor their informant to be able to complete their head-movements upward before she herself has vanished from the place indicated by the black-gloved hand. But her recoil has been so rapid and spontaneous that it is accompanied by a clumsy gesture of her left hand, on which the heavy silver ring has just knocked violently against the pane.

The impact has produced a loud, distinct noise. At the same time has appeared, extending across the entire surface of the rectangle, a star-shaped fracture. But no piece of glass falls out, unless, much later, it is a tiny pointed triangle, about half an inch long, which slowly leans inward and falls on the tiles with a crystalline sound, breaking in its turn into three smaller fragments.

Laura stares a long time at the broken pane, then through the next one, which is similar but intact, at the blue wall of the house on the other side of the street, then at the three tiny splinters of glass scattered on the floor, and again at the starred pane. From the withdrawn position she now occupies in the corridor, she no longer sees the entire street. She wonders if the men watching her have heard the noise of glass breaking and if they can see the hole she has just made in the pane located below and to the left of the iron latch. To be sure, she would have to put her eye to that hole, leaning down to get closer to the window and then gradually raising her face against the pane of glass.

But the lower pane itself may not be hidden from view—may be visible to the man in the black raincoat and soft felt hat—because of the landing of the fire escape, actually a discontinuous structure consisting of parallel strips of iron which are not contiguous and leave openings between them of an equal width through which can be seen, from either side … From this side—that is, from up above, looking down—doubtless more easily, for the metal platform in question is much closer to the window than to the ground. The fact remains nonetheless that the straight line connecting the lower pane to the indented brim of the felt hat may run well above it; and this would be all the more true of the broken pane.

Once again the young woman remembers that her brother has forbidden her, under threat of severe punishment, to show herself at the windows overlooking the street—her brother who must have left the house just when the policemen had reached the neighborhood: she did not see him go out or walk away, but, when he leaves, he stays on the near sidewalk anyway, entirely invisible from the closed window, even to someone who stands right next to the pane.

He may also not yet have gone outside, having had time in the vestibule to realize the danger, inspecting the situation through the opening protected by a grille set in the wood of the door. And he is still, at this very moment, at his concealed observation post, wondering why the three policemen are looking up that way, unless he has immediately understood the reason, having himself heard, from downstairs, the sound of the broken pane which has drawn their attention to the third floor.

And now he is silently coming back upstairs to catch the disobedient girl red-handed: creeping up to a windowpane exposed to all eyes, and this moreover at precisely the moment when the justification for the prohibition is particularly obvious.

After having laid his key as usual on the marble table top, near the brass candlestick, he slowly mounts the steps, one by one, leaning on the wooden banister, for the excessive steepness of the stairs makes him feel once more the accumulated fatigue of the last several days: several days of watchfulness, expectation, of prolonged meetings, of errands by subway or on foot from one end of the city to the other, as far as the most outlying districts, far beyond the river … For how many days?

Having reached the first landing, he stops in order to listen, ears cocked for the faint creaks throughout the building. But there is neither a creak, nor the sound of material tearing, nor breath caught; there is nothing but silence and closed doors along the empty corridor.

He resumes his ascent. Laura, who had knelt on the terra cotta tiles and was beginning to crawl toward the window, in order to see what was happening outside now, suddenly frightened, turns around and sees, only a yard above her face, the man leaning over her whom she has not heard coming, but who suddenly overwhelms her with his motionless and threatening bulk. With the reflex of a child found out, she quickly raises one elbow to protect her face (although he has not made the least gesture of violence toward her) and, attempting at the same time to draw back in order to avoid being slapped, she slips, loses her balance, and sprawls back on the floor, one leg stretched out, the other bent beneath her, the upper part of her body supported on one elbow, the other still crooked in a traditional attitude of frightened defense.

She looks extremely young: perhaps sixteen or seventeen. Her hair is startlingly blond; the loose curls frame her pretty, terrified face with many golden highlights caught in the bright illumination from the window, against which she is silhouetted. Her long legs are revealed as far as the upper part of the thighs, the already short skirt being raised still farther in her fall, which exposes and emphasizes their lovely shape almost up to the pubic region, which can in fact be discerned in the shadows under the raised hem of the material.

Aside from the attitude of the two figures (which indicates both the rapidity of the movement and the violent tension of its suspension) the scene includes an objective trace of struggle: a broken pane whose splinters lie scattered on the regular hexagons of the tiles. The girl moreover has injured her hand, either because she has scraped it on the broken pane as she fell or because she has cut it a few seconds later on the glass splinters lying on the floor, or because she herself has broken the pane in her fall when the man brutally pushed her against the window, unless of course she acted deliberately: breaking the pane with her fist in the hopes of obtaining a glass dagger, as a defensive weapon against an aggressor.

A little bright-red blood, in any case, stains the hollow of her raised palm, and also, upon closer inspection, one of her knees, the one which is bent. This vermilion color is precisely the same as the one which covers her lips, as well as the very small surface of skirt visible in the picture. Above, the young girl is wearing a thin powder-blue garment which clings to her young bosom, a blouse of some shiny material whose neckline seems however to be torn. No earrings, nor necklace, nor bracelet, nor wedding ring is shown, only the left hand wears a heavy silver ring, drawn so carefully that it must play an important part in the story.

The bright-colored poster is reproduced several dozen times, pasted side by side all along the subway passageway. The play’s title is The Blood of Dreams. The male character is a Negro. Till now I have never heard of this show, doubtless a recent one which has not been reviewed in the papers. As for the names of the performers, printed moreover in very tiny letters, they seem quite unknown to me. It is the first time I have seen this advertisement, in the subway or elsewhere.

Deciding that my pause has lasted long enough now to give any possible pursuers the chance to catch up with me, I turn around again and once again observe that no one is following me. The long corridor, from one end to the other, is empty and silent, very dirty like all the rest on this subway line, strewn with various papers, from torn newspapers to candy wrappers, and marked by more or less disgusting damp stains. The brand-new poster which stretches as far as the eye can see, in either direction, also contrasts by its brightness with the remainder of the walls, covered with a ceramic tile which must originally have been white but whose surface is now cracked, chipped, stained with brownish streaks, broken at certain points as though someone had pounded it with a hammer.

At the other end, the corridor opens onto a huge similarly deserted area, an enormous underground hall with no apparent function, in which nothing can be made out that suggests—neither architectural detail nor signboard—any particular direction to follow; unless placards are mounted on certain surfaces but these are so remote, given the considerable dimensions of the place, and its dim illumination, that nothing identifiable is apparent in any direction, the very limits of this useless and vacant interval being lost in the uncertainty of the zones of shadow.

The very low ceiling is supported by countless hollow metal beams, whose four sides are perforated with floral patterns dating from an earlier period. These pillars are quite close together, only about five or six feet apart, set regularly in parallel lines, which divides the entire area into equal and contiguous squares. The checkerboard is moreover materialized on the ceiling by identical rafters jointing the capitals in pairs.

Suddenly the asphalt floor is interrupted, for a considerable length, by a series of stairways with alternating railings, ascending and descending, each of whose first step occupies the entire distance between two ironwork pillars. The whole seems conceived for the flow of a huge crowd which obviously no longer exists in any case at this hour. In two opposing flights, a lower area is reached, resembling the upper one in every particular. On a still lower level, I finally reached the shopping gallery, brilliantly illuminated this time by many-colored harsh bulbs, the more painful to the eyes in that the upper areas were only dimly lit.

And with a similar lack of transition, there is also a crowd now: a rather scattered crowd, but one of regular density, consisting of isolated figures or those grouped by two or, exceptionally, three, occupying the whole of the surface accessible between the stalls as well as that inside them. Here there are only young people, mostly boys, although a close examination reveals among some of these, under the short hair, tight blue jeans, and turtle-neck sweaters or leather jackets, probable or even incontestable girls’ bodies. All are dressed alike, but their beardless pink and blond faces also look alike, with that bright and uninflected coloration which suggests not so much good health as the paint used on store-window mannequins, or the embalmed faces of corpses in glass coffins in the cemeteries of the dear departed. The impression of artificiality is further enhanced by the awkward postures of these young people, doubtless intended to express self-confidence, controlled strength, scorn, arrogance, whereas their stiff attitudes and the ostentation with which every gesture is made actually suggest the constraint of poor actors.

Among them, on the contrary, like tired guards in a wax museum, linger here and there occasional adults of indeterminate age, discreet and inconspicuous as if they were trying not to be seen; and as a matter of fact, it takes a certain amount of time to become aware of their presence. They reveal in their gray faces, their drawn features, their uncertain movements, the quite visible signs of the night hour, already very late. The livid glare of the neon tubes completes the illusion of invalids or addicts; the various races have here become almost the same metallic tinge. The huge greenish mirror of a store window reflects my own quite comparable image.

Nonetheless, old and young possess one characteristic in common, which is the excessive slackening of every movement, whose affected deliberation among some, whose extreme lethargy among others, threaten at any moment a total and definitive breakdown. And all this is, moreover, remarkably silent: neither shouts nor words spoken too loud, nor racket of any kind manages to disturb the muffled, padded atmosphere, broken only by the clicking of slot-machine levers and the dry crackling or clatter of scores automatically registered.

For this underground area seems entirely devoted to amusements: on each side of the huge central mall open out huge bays filled with long rows of the gleaming garish-painted devices: slot machines whose enigmatic apertures, which respectively devour and spit forth change, are embellished so as to make more obvious their resemblance to the female organ, games of chance allowing the player to lose in ten seconds some hundreds of thousands of imaginary dollars, automatic distributors of educational photographs showing scenes of war or copulation, pinball machines whose scoreboards include a series of villas and limousines, in which fires break out as a result of the movements made by the steel balls, shooting galleries with tracer bullets trained on the pedestrians in an avenue set up as the target, dartboards representing the naked body of a pretty girl crucified against a stake, racing cars driven by remote control, electric baseball, stereopticons of horror films, etc.

There are also, alongside, huge souvenir shops in which are set out, arranged in parallel rows of identical objects, plastic reproductions of world capitals and famous structures, ranging, from top to bottom of the display, from the Statue of Liberty, the Chicago stockyards, to the giant Buddha of Kamakura, the Blue Villa in Hong Kong, the lighthouse at Alexandria, Christopher Columbus’ egg, the Venus of Milo, Greuze’s Broken Pitcher, the Eye of God carved in marble, Niagara Falls with its wreaths of mist made out of iridescent nylon. Lastly there are the pornographic bookshops, which are merely the extension in depth of those of Forty-Second Street, a few yards, or dozen of yards, or hundreds of yards up above.

I discover without difficulty the shop window I want, easily found because it displays nothing: it is a wide plain ground-glass sheet with the simple inscription in moderate-sized enamel letters: “Dr. Morgan, Psychotherapist.” I turn the nearly invisible handle of a door made of the same ground glass, and I step into a very small bare cubicle, all six surfaces painted white (in other words, the floor as well), in which are only a tubular-steel chair, a matching table with an artificial marble top on which is lying a closed engagement book whose black imitation-leather cover shows the date “1969” stamped in gold letters, and behind this table, sitting very stiffly on a chair identical with the first, a blond young woman—quite pretty perhaps, impersonal and sophisticated in any case, wearing a dazzlingly white nurse’s uniform, her eyes concealed by sunglasses which doubtless help her endure the intense lighting, white like everything else and reflected on all sides by the immaculate walls.

She looks at me without speaking. The lenses of her sunglasses are so dark that it is impossible to guess even the shape of her eyes. I bring myself to pronounce the sentence, carefully separating the words as if each of them contained an isolated meaning: “I’ve come for a narco-analysis.”

After a few seconds thought, she gives me the anticipated reply, but in an oddly natural voice, gay and spontaneous, suddenly bursting out: “Yes … It’s quite late … What’s the weather like outside right now?” And her face immediately freezes again, while her body has regained its mannequin stiffness at the same time. But I answer right back, still in the same neutral tone, insisting on each syllable: “It’s raining outside. People are walking with their heads bent under the rain.”

“All right,” she says (and suddenly there is a kind of weariness in her voice), “are you a regular patient or is this your first visit?”

“This is my first visit here.”

Then after having looked at me again for a moment—at least so it seems to me—through her dark glasses, the young woman stands up, walks around the table and, though the narrowness of the room does not at all require her to do so, brushes against me so insistently that her perfume clings to my clothes; in passing she points to the empty chair, continues to the far wall, turns around and says to me: “Sit down.”

And she has immediately vanished, through a door so well concealed in the white partition that I had not even noticed its glass knob. The continuity of the surface is re-established, moreover, so quickly that I could now suspect I never saw it broken. I have just sat down when, through the opposite door opening onto the shopping mall, walks one of the men with iron-gray faces I glimpsed a few minutes earlier standing in front of a bookshop window: his body was turned toward the row of specialized magazines and papers on display, but he kept glancing right and left, as if he was afraid of being watched, though at times his eyes rested with some deliberation on an expensive magazine of which an entire row of identical copies were displayed at eye level, showing on its cover the full-color photograph, life size, of an open vagina.

Now he is looking at me, then at the table and the empty chair behind it. Finally he brings himself to pronounce the sentence: “I’ve come for a narco-analysis.” Without omitting or changing a single word, I could give him the right answer, but it does not seem to me to be my part to do so; therefore I speak no more than the beginning, in order to reassure him even so: “Yes … It’s quite late.” Then I improvise: “The doctor’s assistant has gone out. But I think she’ll be right back.”

“Oh good. Thank you,” the gray-faced man says, turning toward the ground-glass window opening onto the mall, exactly as if he could see through it and had chosen this sight as a diversion, to help pass the time.

Suddenly I am filled with suspicion as I notice the way in which the newcomer is dressed: shiny black raincoat and soft felt hat with the brim turned down … Unless his back merely reminds me of the disturbing figure I have just seen pressed up against the display of the pornographic bookstore … But now the man, as though to give more consistency to the disturbing connection I cannot help making, straightening up in his raincoat, thrusts his gloved hands deep into its broad pockets.

Without leaving me time to wait for the man to show his face again, so that I might recognize what he looks like even when his features are drawn by fatigue, the young woman in the nurse’s uniform returns and very quickly gets rid of me. According to her directions, I leave through the rear door with the glass knob and climb a steep narrow spiral staircase made of cast iron.

Then there is a long corridor entirely covered (except for the floor) with that dilapidated white ceramic tile already described during the passage through the subway station, in which, as a matter of fact, I must still be walking. At the end of the hallway, a tiny sliding door with an electric-eye device opens automatically to let me through, and finally I enter the room where, if I have understood correctly, we are to be given our orders for tomorrow. Here there are some fifty persons. I immediately wonder how many police informers there can already be among them. Since I have come in at the rear of the room, I see the people in it only from the back, which does not make any such estimate easy—in fact, ridiculous.

I imagined I was ahead of time; it appears on the contrary that the meeting has already been going on for some time. And it is not concerned with the usual specific details, concerning imminent action. Instead, today, the meeting is given over to a kind of ideological discussion presented in the usual form, whose didactic effectiveness on the militants of every persuasion has been readily acknowledged: a prefabricated dialogue between or among three persons assigned alternately questions and answers, changing parts by a circular permutation at each shift of the text—i.e., about every minute.

The sentences are short and simple—subject, verb, complement—with constant repetitions and antitheses, but the vocabulary includes quite a large number of technical terms belonging to various fields, philosophy, grammar, or geology, which keep turning up. The tone of the speakers remains constantly neutral and even, even in the liveliest moments; the voices are polite, almost smiling despite the coolness and exactitude of their elocution. They all three know their parts down to the last comma, and the whole scenario is articulated like a piece of machinery, without a single hesitation, without a slip of memory or the tongue, in an absolute perfection.

The three actors are wearing dark suits of severe cut, with impeccable shirts and striped ties. They are sitting side by side on a little platform, behind a rickety wooden table, like the kind that used to be seen in poor men’s kitchens. This piece of furniture is therefore more or less in harmony with the walls and ceiling of the room which are here, too, covered with the same dilapidated ceramic tiles, which slow infiltrations of moisture have loosened in irregular patches, revealing grayish surfaces of crude concrete, confined to the edges of the tile by crenellations or ladder-shaped areas. The theme of the day’s lecture seems to be “the color red,” considered as a radical solution to the irreducible antagonism between black and white. Right now each of the three voices is devoted to one of the main liberating actions related to red: rape, arson, murder.

The preliminary section, which was ending when I arrived, must have been devoted to the theoretical justifications of crime in general and to the notion of metaphorical acts. The performers are now dealing with the identification and analysis of the three functions in particular. The reasoning which identifies rape with the color red, in cases where the victim has already lost her virginity, is of a purely subjective nature, though it appeals to recent studies of retinal impressions, as well as to investigations concerning the religious rituals of Central Africa, at the beginning of the century, and the lot of young captives belonging to races regarded as hostile, during public ceremonies suggesting the theatrical performances of antiquity, with their machinery, their brilliant costumes, their painted masks, their paroxysmal gestures, and that same mixture of coolness, precision, and delirium in the staging of a mythology as murderous as it is cathartic.

The crowd of spectators, facing the semicircle formed by the curved row of oil palms, dances from one foot to the other, stamping the red-earth floor, always in the same heavy rhythm which nonetheless gradually accelerates. Each time a foot touches the ground, the upper part of the body bends forward while the air emerging from the lungs produces a wheezing sound which seems to accompany some woodcutter’s laborious efforts with his ax or some farmer’s with his hoe. Without my being able to account for it, I keep remembering the sophisticated young woman disguised as a nurse who receives the so-called patients of Doctor Morgan in the brightly lighted little room precisely when she brushes past me with her dyed-blond hair and her doubtless artificial breasts that swell the white uniform and her violent perfume.

She prolongs the contact insistently, provocatively, inexplicably. As if an invisible obstacle stands in the middle of the room which she must pass on my side by undulating her hips in a kind of vertical slither, in order to get through the narrow space. And meanwhile, the stamping of bare feet on the clay floor continues in an accelerating cadence, accompanied by an increasingly raucous collective gasping, which finally drowns out the noise of the tom-toms beaten by musicians crouched in front of the dancing area, their row closing off the half-circle of palm trees.

But the three actors, on the dais, have now come to the second panel of their triptych, in other words, to the murder; and the demonstration can this time, on the contrary, remain on a perfectly objective level while being based on the blood spilled, provided nonetheless it is limited to methods provoking a sufficiently abundant external bleeding. The same is then the case for the third panel, which relates to the traditional color of flames, approached most nearly by using gasoline to start the fires.

The spectators, seated in parallel rows on their kitchen chairs, are as motionless in their religious attention as rag dolls. And since I have remained at the very back of the room, standing against the wall since there was no empty seat, and since as a result I see only their backs, I can suppose that they have no faces at all, that they are merely stuffed figures surmounted by clipped and curled wigs. The speakers, on their side, moreover, perform their parts in an altogether abstract fashion, always speaking quite frontally without their eyes coming to rest on anything, as if there were no one facing them, as if the room were empty.

And it is in chorus now, all three reciting the same text together, in the same neutral and jerky voices in which no syllable stands out, that they present the conclusion of the account: the perfect crime, which combines the three elements studied here, would be the defoliation, performed by force, of a virgin, preferably a girl with milky skin and very blond hair, the victim then being immolated by disembowelment or throat-cutting, her naked and bloodstained body having to be burned at a stake doused with gasoline, the fire gradually consuming the whole house.

The scream of terror, of pain, of death, still fills my ears as I contemplate the heap of crumpled bedclothes spread like so many rags on the floor, an improvised altar whose folds are gradually dyed a brilliant red, in a stain with distinct edges which, starting from the center, rapidly covers the entire area.

The fire on the contrary, once the match has grazed a shred of lace soaked in gasoline, spreads through the whole mass all at once, immediately doing away with the lacerated victim who is still stirring faintly, the heap of linen used in the sacrifice, the hunting knife, the whole room from which I have just had time to make my escape.

When I get to the middle of the corridor, I realize that the fire is already roaring in the elevator shaft, from top to bottom of the building, where I have lingered too long. Luckily there remained the fire escapes, zigzagging down the façade. Reversing my steps, then, I hurry toward the French window at the other end. It is locked. No matter how hard I press the catch in every direction, I cannot manage to release it. The bitter smoke fills my lungs and blinds me. With a sharp kick, aimed at the bottom of the window, I send the flat of my sole through four panes and their wooden frames. The broken glass tinkles shrilly as it falls out onto the iron platform. At the same time, reaching me along with the fresh air from outside and drowning out the roar of the flames, I hear the clamor of the crowd which has gathered in the street below.

I slip through the opening and I begin climbing down the iron steps. On all sides, at each floor, other panes are exploding because of the heat of the conflagration. Their tinkling sound, continuously amplified, accompanies me in my descent. I take the steps two at a time, three at a time.

Occasionally I stop a second to lean over the railing: it seems to me that the crowd at my feet is increasingly far away; I no longer even distinguish from each other the tiny heads raised toward me; soon there remains no more than a slightly blacker area in the gathering twilight, an area which is perhaps merely a reflection on the sidewalk gleaming after the recent shower. The shouts from a moment ago already constitute no more than a vague rustle which melts into the murmur of the city. And the warning siren of a distant fire engine, repeating its two plaintive notes, has something reassuring about it, something peaceful, something ordinary.

I close the French window, whose catch needs to be oiled. Now there is complete silence. Slowly I turn around to face Laura, who has remained a few feet behind me, in the passageway. “No,” I say, “no one’s there.”

“All the same, he stayed out there, as if he was on sentry duty, all day long.”

“Well, he’s gone now.”

In the corner of the recess formed by the building opposite, I have just caught sight of the black raincoat made even shinier by the rain glistening in the yellow light of a nearby streetlamp.

I ask Laura to describe to me the man she is talking about; she immediately gives me the information already known, in a slow voice, uncertain in its elocution but specific in its remembered details. I say, to make conversation: “Why do you think he is watching this particular house?”

“At regular intervals,” she says, “he looks up toward the windows.”

“Which windows?”

“This one and the ones of the two empty rooms on each side.”

“Then he saw you at this one?”

“No, he couldn’t have: I’m too far back and the room is too dark inside. The panes only reflect the sky.”

“How do you know? Did you go out?”

“No! Oh no!” She seems panic-stricken at the idea. Then, a few seconds later, she adds, more calmly: “I figured it out—I made a sketch.”

I say: “In any case, since he’s gone, he must have been watching something else, or just waiting there, hoping that the rain would stop so he could be on his way.”

“It didn’t rain all day,” she answers. And I can tell, from the sound of her voice, that in any case she doesn’t believe me.

Once again I think that Frank must be right: this girl represents a danger, because she tries to find out more than she can stand knowing. A decision will have to be made.

“Besides, he was already there yesterday,” Laura says.

I take a step in her direction. She immediately steps back, keeping her timid eyes fixed on mine. I take another step, then a third. Each time, Laura retreats the same distance. “I’m going to have to …” I began, looking for the right words …

At that very moment, over our heads, we could hear something: low but distinctly audible, like three taps someone makes on a door if he wants to go into one of the rooms. All these rooms are empty, and there is no one but ourselves in the building. It might have been a beam creaking, which had seemed abnormally distinct to us because we ourselves were making so little noise, measuring our steps across the tiles. But Laura, half-whispering, said: “Did you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

“Someone knocking.”

“No,” I say, “that was me you heard.”

I had then reached the stairs, and rested one hand on the banister. To reassure her, I tapped three times with the tip of one fingernail on the wooden rail without moving my palm or the other fingers. Laura gave a start and looked at my hand. I repeated my gesture, under her eyes. Despite the verisimilitude of my imitation, she must not have been altogether convinced. She has glanced up at the ceiling, then back at my hand. I have begun walking slowly toward her, and at the same time she has continued moving back.

She had almost reached the door of her room in this manner, when once again we heard that same noise on the floor above, We both stopped and listened, trying to determine the place where it seemed to be coming from. Laura murmured in a very low voice that she was frightened.

I no longer had my hand on the railing, now, nor on anything at all. And it was difficult for me to invent something else of the same kind. “Well,” I say, “I’ll go up and see. But it’s probably only a mouse.”

I have turned around at once to return to the stairwell. Laura has hurried back into her room, trying to lock the door from inside with the key. In vain, of course, for the keyhole has been jammed ever since I put a nail into it, for just that purpose. As usual, Laura struggled a few moments, without managing to make the bolt work; then she gave up and walked over to the still open bed, where she has doubtless hidden herself, fully dressed. She has not even had to take off her shoes, since she is always barefoot, as I believe I have already indicated.

Instead of going up to the rooms above, I have immediately begun walking downstairs. The house, as I have said, consists of four identical stories, including the ground floor. There are five rooms on each floor, two of which look out on the street and two, in the rear, on the courtyard of a city school for girls; the last room, which faces the stairs, has no windows. At the level where we sleep, in other words the third floor, this blind room is a very large bathroom. We also use a few rooms of the ground floor: the one, for example, which I have called the library. All the rest of the house is uninhabited.

“Why?”

“The whole building includes, according to what I have just said, twenty rooms. Which is far too many for two people.”

“Why did you rent such a big house?”

“No, I’m not the tenant, only the watchman. The owners want to pull it down, so as to build something higher and more modern. If they were to rent apartments or rooms, that might create difficulties during the demolition.”

“You haven’t finished the story of the fire. What happened when the man coming down the fire escape reached the ground?”

“The firemen had put a little ladder between the lowest platform of the fire escape and the ground. The man with the gray face let himself tumble down, rather than actually climb the last rungs. The lieutenant fireman has asked him if there was still anyone in the building. The man has answered without a moment’s hesitation that there was no one left. An elderly woman, who was in tears and had barely—as I understood it—escaped the flames, has repeated for the third time that a ‘young lady,’ who lived over her own room, had disappeared. The man has declared that the floor in question was empty, adding that doubtless this blond girl had already left her room when the fire broke out, perhaps in her very room: if she had forgotten to unplug an electric iron, or left on a gas burner, or an alcohol lamp …”

“And then what did you do?”

“I managed to lose myself in the crowd.”

He finishes writing what interests him in the report I have just made. Then he looks up from his papers and asks, without my seeing the link with what has preceded: “Was the woman you call your sister in the house at that time?”

“Yes, of course, since she never goes out.”

“You’re sure of that?”

“Yes, absolutely sure.”

Previously, and without any more reason, he had asked me how I accounted for the color of Laura’s eyes, her skin, and her hair. I had answered that there had probably been some kind of mix-up. This interview over, I walked toward the subway, in order to go back home.

Meanwhile, Laura is still huddled under her sheets and blankets, pulled up over her mouth. But her eyes are wide open, and she is listening hard, trying to figure out what is happening overhead. Yet there is nothing to hear, so heavy and ominous is the silence of the whole house. At the end of the hallway, the murderer, who has quietly climbed up the fire escape, is now carefully picking up the pieces of broken glass which he found broken when he reached the window; thanks to the hole left by the little triangle of windowpane which had already fallen out, the man can grasp one by one between two fingers the sharp points which constitute the star and remove them by pulling them out from their groove between the wood frame and the dry putty. When he has, without hurrying, completed this task, he need merely thrust his hand through the gaping rectangle, where he no longer risks severing the veins in his wrist, and turn the recently oiled lock without making any noise at all. Then the window frame pivots silently on its hinges. Leaving it ajar, ready for his escape once his triple crime has been committed, the man in black gloves walks silently across the brick tiles.

Already the door handle moves slightly. The girl, half-sitting up in her bed, stares wide-eyed at the brass knob facing her. She sees the gleaming spot which is the reflection of the tiny bedlamp in the polished metal turning with unbearable deliberation. As if she were already feeling the sheets crushed beneath her covered with blood, she utters a scream of terror.

There is light under the door, since I have just pressed the hall-light button on my way up. I tell myself that Laura’s screams will end by disturbing our neighbors. During the day, the schoolchildren hear them in their courtyard. I climb the stairs wearily, legs heavy, exhausted by a day of errands even more complicated than usual. I even need, tonight, the banister to lean on. At the second-floor landing, I carelessly drop my keys, which clatter against the iron bars before they reach the floor. I then notice that I have forgotten to set these keys down on the vestibule table downstairs, as I usually do each time I come in. I attribute this negligence to my exhaustion and to the fact that I was thinking about something else as I was closing my door: once again, about what Frank had just told me with regard to Laura, and which I should probably consider as an order.

This had happened at “Old Joe’s.” The band there makes such a racket that you can talk about your business without danger of being overheard by indiscreet ears. Sometimes the problem is actually to make yourself heard by the person you are talking to, whose face you get as close to as you can. At our table, there was also, at first, the go-between who calls himself Ben-Saïd, who as usual said nothing in the presence of the man whom we all more or less regard as the boss. But when Frank got up and walked toward the men’s room (or, more likely, the telephone), Ben-Saïd told me right away that I was being followed and that he wanted to warn me. I pretended to be surprised and asked if he knew why.

“There are so many informers,” he answered, “it’s only natural to be careful.” He added that in his opinion, moreover, almost all the active agents were watched.

“Then why tell me about it—me in particular?”

“Oh, just so you’ll know.”

I looked at the people at the other tables around us, and I said: “So my shadow is here tonight? You should tell me which one he is!”

“No,” he answered without even turning his head to make sure, “here it’s no use, there are almost no men here except our own. Besides, I think it’s actually your house that’s being watched.”

“Why my house?”

“They think you’re not living there alone.”

“Yes I am,” I say after a moment’s thought, “I’m living alone there now.”

“Maybe you are, but they don’t seem to think so.”

“They better let me know what they do think,” I say calmly, to put an end to this conversation.

Frank was just coming back from the men’s room. Passing by one of the tables, he said something to a man who immediately stood up and walked over to get his raincoat, hanging on a peg. Frank, who had continued on his way, then reached his chair. He sat down and said curtly to Ben-Saïd that everything was set, he should be on his way there now. Ben-Saïd left without asking for another word of information, even forgetting to say good-by to me. It was right after he left that Frank spoke to me about Laura. I listened without answering. When he finished: “That’s it, you take it from there,” I finished my Bloody Mary and went out.

In the street, just in front of the door, there were two homosexuals, walking arm in arm with their little dog on a leash. The taller one turned around and stared at me with an insistence I couldn’t explain. Then he whispered something into his friend’s ear, while they continued their stroll, walking with tiny steps. I thought that maybe I had a speck of dirt somewhere on my face. But when I rubbed the back of my hand over my cheeks, all I could feel were the hairs of my beard.

At the first shopwindow I came to, I stopped to examine my face in the glass. At the same time I took advantage of the occasion to glance back and I glimpsed Frank coming out of “Old Joe’s.” He was accompanied by Ben-Saïd, I am ready to swear to it, though the latter had already left at least three-quarters of an hour before. They were walking in the opposite direction from mine, but I was afraid one or the other would turn around, and I pressed up closer against the glass, as if the contents of the shopwindow were enormously interesting to me. It was only the wig-and-mask shop, though, whose display I have been familiar with for a long time.

The masks here are made out of some soft plastic material, very realistically fashioned, and bear no relation to those crude papier-mâché faces children wear at Halloween. The models are made to measure according to the customer’s specifications. In the middle of the objects exhibited in the window, there is a large placard imitating hurriedly daubed-on graffiti: “If you don’t like your hair, try ours. Feel like jumping out of your skin? Jump into ours!” They also sell foam-rubber gloves which completely replace the appearance of your hands—shape, color, etc.—by a new external aspect selected from a catalogue.

Framing the central slogan on all four sides, are neatly lined up the heads of some twenty presidents of the United States. One of them (I forget his name, but it’s not Lincoln) is shown at the moment of his assassination, with the blood streaming down his face from a wound just over the brow ridge; but despite this detail, the facial expression is the calm smiling one which has been popularized by countless reproductions of every kind. These masks, even the ones without a bullet hole in them, must be on display only to indicate the extreme skill of the establishment (so that passers-by can discover the lifelike character of the resemblance to familiar features, including those of the president in office who is seen every day on the television screen); they are certainly not often used here in town, contrary to the anonymous faces which constitute the lower row, each accompanied by a brief caption to indicate its use and merits to the shop’s clientele, for instance: “Psychoanalyst, about fifty, distinguished and intelligent; attentive expression despite the signs of fatigue which are the mark of study and hard work; worn preferably with glasses.” And next to it: “Businessman, forty to forty-five, bold but serious; the shape of the nose indicates shrewdness as well as honesty; an attractive mouth, with or without mustache.”

The wigs—for both sexes, but particularly for women—are set in the upper part of the window; in the middle, a long cascade of blond hair dangles in silky curls down to the forehead of one of the presidents. Finally, at the very bottom, paired on a strip of black velvet laid flat, false breasts (of all sizes, curves and hues, with various nipples and aureoles) are set out for—so it seems—at least two functions. As a matter of fact, a little diagram on one side shows the way of attaching them to the chest (with a variant for male bodies), as well as the way of keeping the edges imperceptible, for only this delicate point can betray the device, so perfect is the imitation of the flesh as well as of the texture of the skin. And elsewhere, however, one of these objects—which also belongs to a pair, the second breast being intact—has been riddled with many needles of various sizes, to show that it can also be used as a pincushion. All the facsimiles exhibited here are so lifelike that it is surprising not to see forming, on the pearly surface of this last one, tiny ruby drops.

The hands are scattered all over the shopwindow. Some are arranged so as to form anecdotal elements in contact with some other article: a woman’s hand on the mouth of the old “avant-garde artist,” two hands parting a mass of auburn hair, a very black hand—a man’s hand—squeezing a pale pink breast, two powerful hands clutching the neck of the “movie starlet.” But most of the hands soar through the air, agile and diaphanous. It even seems to me that there are a lot more of them tonight than on other days. They move gracefully, hanging on invisible threads; they open their fingers, turn over, revolve, close. They really look like the hands of lovely women recently severed—several of them, moreover, have blood still dripping from the wrist, chopped off on the block with one stroke of a well-sharpened axe.

And the decapitated heads too—I had not noticed it at first—are bleeding profusely, those of the assassinated presidents, but all the rest even more: the lawyer’s head, the psychoanalyst’s, the car salesman’s, Johnson’s, the waitress’s, Ben-Saïd’s, the trumpet-player at “Old Joe’s” this week, and the head of the sophisticated nurse who receives patients for Doctor Morgan in the corridors of the subway station of the line I then take to get back home.

On my way upstairs, as I reach the second-floor landing, I happen to drop my keys, which ring against the iron bars of the banister before falling on the last step. It is then that Laura, at the end of the corridor, begins screaming. Luckily, her door is never locked. I walk into her room, where I find her half-naked, crouching in terror on her rumpled bed. I calm her by the usual methods.

Then she asks me to tell her about my day. I tell her about the example of arson which has destroyed a whole building on One Hundred and Twenty-third Street. But since she soon starts asking too many questions, I change the subject by telling her the story—I saw it myself only a little while later—of that ordinary couple who visited the mask-maker on the advice of the family physician: they each wanted to order the other’s face, in order to be able to act out in reverse the psychodrama of their conjugal difficulties. Laura seems amused by this situation, to such a degree in fact that she forgets to ask me what I was doing in such a shop and how I could have managed to hear what was said. I do not tell her that the shopkeeper works with us, nor that I suspect him of being a cop. Nor do I tell her about JR’s disappearance and the investigations into her case which have taken up most of my working time.

It is at the office that I hear the news. I have already told how this office works. To all appearances, it is a placement office of the United Manichean Church. But in reality, the domestics by-the-month, lady’s companions or various slaves, the part-time secretaries, the high-school-student baby-sitters, the call girls paid by the hour, etc, are so many information agents—of organized crime and propaganda—which we thereby manage to introduce into the establishment. The rings of call girls, high-class prostitutes and concubines obviously constitute our best cases, since from them we get both irreplaceable contacts with men in office and also the larger part of our financial resources, not to mention the possibility of blackmail.

JR had been placed as a baby-sitter the week before, in answer to a tiny advertisement in The New York Times: “Unmarried father wants young girl, pleasant appearance, docile character, for night sessions with rebellious child.” The child in question actually existed, despite the oddly promising text of the advertisement: the words “docile” and “authoritarian” figuring, as is well known, high on the list of specialists’ code words. In principle, what was involved should have been the participation in the training of a novice mistress, giving her if need be a good example of submission.

Therefore we sent JR, a handsome white girl with a fine head of auburn hair which always creates a good effect in intimate scenes, who had already handled similar cases on several occasions. She arrives that same evening at the address given, on Park Avenue, between Fifty-sixth and Fifty-seventh Streets, wearing a very short, close-fitting green silk dress which has always given us good results. To her great surprise, it is a little girl of twelve or a little older who opens the door; she is alone in the apartment, she says in answer to JR’s embarrassed question, her name is Laura, she is thirteen and a half, and she offers JR a glass of bitter lemon while they chat, to get to know each other …

JR insists: “I really wanted to see your father …” But the little girl immediately declares, quite offhandedly, that in the first place that is impossible, since he’s gone out, and besides, “you know, he’s not really my father…,” these last words whispered in a much lower tone, confidentially, with a tiny smothered laugh to end the sentence in a very good imitation of polite embarrassment. Having absolutely no interest in the problem of adopted or illegitimate children, JR would have been ready to leave right away, if the opulence of the house—the avant-garde millionaire style—hadn’t made her stay after all, to satisfy her professional conscience. So she drank the lemon the little girl served her in a kind of boudoir where the seats and little tables were inflated by pressing on electric buttons. To make conversation, and also because it might be a useful piece of information under other circumstances, she asked if there were no servants.

“Well, there’s you,” Laura answered, with her prettiest smile.

“No, I mean, to do the housework, the cooking …”

“You don’t plan to do any housework?”

“Well, I … I didn’t think that was what I came for … There’s no one else?”

The little girl’s expression now contrasted with her previous simperings of a child pretending to be the lady of the house. And in a very different tone of voice, remote and as though filled with melancholy, or despair, she finally said, as if with great reluctance: “There’s a black woman, mornings.”

Then neither of us said another word for what seemed to me quite a long time. Laura sipped her bitter lemon. I decided she was unhappy, but I wasn’t there to deal with that question. And at that moment, there were steps in the next room, heavy and determined steps on a creaking floorboard; at first I didn’t think of how old it was to have that kind of floor in such an apartment building. I said: “Is there someone next door?”

The child answered: “No,” with that same remote expression.

“But I just heard someone walking … Listen, there it is again! …”

“No, it can’t be, there’s never anyone there,” she answered, in her most stubborn manner, against all appearances.

“Then perhaps you have neighbors?”

“No, there are no neighbors. This is all the apartment!” And with a sweeping gesture, she included the vicinity of the boudoir in all directions.

Nonetheless she got up from her pneumatic chair and took a few nervous steps to the large bay window which seemed to open onto nothing but the unvarying gray sky. That was when I noticed how silent her own footsteps remained on the white carpeting thick as fleece, even when she tapped on the floor with her little black patent-leather shoes.

If little Laura’s intention had been to drown out by her movements the noises of the adjoining room, it was a miscalculation in any case, especially since they continued all the louder behind the partition, from which came now the quite recognizable echoes of a struggle: trampling, furniture knocked over, heavy breathing, clothes ripped, and even, soon after, groans, muffled pleas, as though uttered by a woman who for unknown reasons dares not raise her voice, or is materially prevented from doing so.

The little girl, too, was listening now. When the moaning assumed a more particular character, she gave me a sidelong glance, and I had the impression that a fugitive smile passed across her lips, or at least between her half-closed eyelids which had perceptibly winked. But then there was a fierce scream, so violent that she made up her mind to go and see, though without seeming in any way surprised or alarmed.

Having left my seat at the same moment, in an instinctive movement, I saw the door close behind Laura; then, since there was nothing more to be heard, I turned my head toward the sheet of glass. I was thinking, of course, of the fire escape; but aside from the fact that no such thing exists on any building of recent construction, I would have been very reluctant to use, once again, this convenient means of regaining the street, the subway, my abandoned house … In a few meditative steps, however, I reach the huge bay window, and raise the thick tulle curtains covering it.

I am then amazed to discover that the room we were in overlooks Central Park, which seems to me quite impossible, given the position of the building JR entered a few minutes earlier. It would have required, in other words, that the complicated route she took to the apartment door from the entrance lobby, by various elevators and escalators, made her pass under at least one street. But now these topographical reflections divert me to a scene which is taking place at the very bottom, between the bushes, not far from a streetlamp casting a dim light over the figures, distorting their shadows.