Читать книгу Not My Father's Son - Alan Cumming - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHEN

You need a haircut, boy!”

My father had only glanced at me across the kitchen table as he spoke but I had already seen in his eyes the coming storm.

I tried to speak but the fear that now engulfed me made it hard to swallow, and all that came out was a little gasping sound that hurt my throat even more. And I knew speaking would only make things worse, make him despise me more, make him pounce sooner. That was the worst bit, the waiting. I never knew exactly when it would come, and that, I know, was his favourite part.

As usual we had eaten our evening meal in near silence until my father had spoken. Until recently my older brother, Tom, would have been seated where I was now, helping to deflect the gaze of impending rage that was now focused entirely upon me. But Tom had a job now. He left every morning in a shirt and tie and our father hated him for it. Tom was no longer in his thrall. Tom had escaped. I hadn’t been so lucky yet.

My mother tried to intervene. “I’ll take him to the barber’s on Saturday morning, Ali,” she said.

“He’ll be working on Saturday. He’s not getting away with slouching off his work again. There’s too much of that going on in this house, do you hear me?”

“Yes,” I managed.

But now I knew it was a lost cause. It wasn’t just a haircut, it was now my physical shortcomings as a labourer, my inability to perform the tasks he gave me every weekend and many evenings, tasks I was unable to perform because I was twelve, but mostly because he wanted me to fail at them so he could hit me.

You see, I understood my father. I had learned from a very young age to interpret the tone of every word he uttered, his body language, the energy he brought into a room. It has not been pleasant as an adult to realise that dealing with my father’s violence was the beginning of my studies of acting.

“I can get one tomorrow at school lunchtime.” My voice trailed off in that way I knew sounded too pleading, too weak, but I couldn’t help it.

“Yes, do that, pet,” my mum said, kindly.

I could sense the optimism in her tone and I loved her for it. But I knew it was false optimism, denial. This was going to end badly, and there was no way to prevent it.

Every night getting off the school bus, walking through the gates of the estate where we lived, past the sawmill yard where my father reigned, and towards our house was like a lottery. Would he be home yet? What mood would he be in? As soon as I entered the house and changed out of my school uniform and began my chores—bringing wood and coal in for the fire, starting the fire, setting the table, warming the plates, putting the potatoes on to boil—I felt a bit safer. You see, by then I was on his territory, under his command, I worked for him, and that seemed to calm my father, as though my utter servitude was necessary to his well-being. I still wasn’t completely safe of course—I was never safe—but those chores were so ingrained in me and I felt I did them well enough that even if he did inspect them I would pass muster, so I could breathe a little easier until we sat down to eat.

My father was the head forester of Panmure Estate, a country estate near Carnoustie, on the east coast of Scotland. The estate was vast, with fifty farms and thousands of acres of woodland covering over twenty-one square miles of land. We lived on what was known as the estate “premises”, the grounds of Panmure House, though by the time we lived there the big house was long gone. In 1955, as one of many such austerity measures forced upon the landed aristocracy, its treasures were dismantled and then explosives razed it to the ground. All that remained were the stables, where on chilly Saturday mornings during hunting season I’d report, banging my wellies together to keep the feeling in my toes, to work as a beater, hitting trees with a stick in a line of other country boys, scaring the birds up into the air so that drunk rich men could shoot at them.

Attached still to the stables was the building that had been the house’s chapel. Now it was used for the annual estate Christmas party and occasional dances or card game evenings for the workers. We lived in Nursery House, so called because it looked out on a tree nursery where seedlings were hatched and nurtured to replace the trees that were constantly felled and sent back to the sawmill that lay up the yard behind us. My father was in charge of the whole process, from the seeds all the way to the cut lumber and everything in between, as well as the general upkeep of the grounds.

It was all very feudal and a bit Downton Abbey, minus the abbey and fifty years later. I answered the door to men who referred to my father as “The Maister”. There were gamekeepers and big gates and sweeping drives and follies but no lord of the manor, as during the time we lived there the place was owned by, respectively, a family shipping company, a racehorse owner’s charitable trust, and then a huge insurance company.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was living through the end of an era of grand Scottish estates, as now, like Panmure, they have been mostly all dismantled and sold off. Looking back on it, it was a beautiful place to grow up, but at the time all I wanted was to get as far away as possible.

I had seen my father’s van parked by the tractor shed as I walked by. So he was home. But maybe he wasn’t actually in the house, maybe he was talking to one of his men in the sawmill or in one of the storehouses or sheds. It was the time of day when they were coming back from the woods and cleaning their tools before going home. I couldn’t see my dad, although I didn’t want to be seen to be looking for him in case he spotted me and he’d know that my fear was guiding my search. That would be his opening. Maybe there would be someone in the yard who’d come to see him, a farmer or even his boss, the estate factor (or manager), who would allow me to get by him without inspection.

I turned round the corner into the driveway of our house at the bottom of the sawmill yard, and I could see there was a light on in his office. My heart sank. He was sitting at his desk in the window and he looked up when he saw me. Immediately I straightened, tried to remember all the things he’d told me were wrong about me recently. I prayed my hair was combed the way he liked it, my school bag was hanging on my shoulder at the right angle, and my shoes were shiny enough. It probably took only ten seconds before I reached the front door and was out of his sight, but in that flash a myriad of anxieties about my flaws and failures had whirred across my mind.

He was on the phone, thankfully. He didn’t come out of his office even until after my mum came home from work, and I always felt a little lighter having her in the house. She finished making our tea while we chatted. Then we heard the noise of him approaching through the house towards us and we were quiet. We both knew it was not a good idea to speak until we had appraised him, and tonight apparently it was not a good idea to speak at all.

My father sat into his chair at the kitchen table and immediately my mother set down his plate of food in front of him. This is how it always happened. Any deviation, let alone any complaint about the food, could start him off. Without acknowledging her or me he lifted his cutlery and began to eat. He ate like an animal, not because he was messy or noisy, but because he tore at his food, with strength and stealth and efficiency. It was terrifying to watch.

My father was silent for a while after my mum spoke, and I hoped that my going to the barber’s during school lunch break the next day would appease him. All I could think of was getting to the end of this meal and upstairs to my homework, or better yet far into the woods with my dog to hide. But my mouth was so dry, and there was a lump of fear stuck at the top of my chest that made it hard to swallow. I had to get some water or I was going to choke, or worse, cry. I got up from the table and moved towards the sink. I picked up a glass off the draining board and began to fill it.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” he said, not quite shouting yet, but still too loud, as though he had been waiting to say it, eager to make the next move, and now here it was.

“Eh? Did you hear me?”

“I need to drink some water,” I gasped.

“Put that glass down!” Now he was shouting.

My mother said very quietly, “Ali, leave him.”

My father rose from his chair and everything went red. At the same time as he began shouting at me he grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and I was being dragged across the kitchen, through the living room, through the hallway, out through the porch and the front door and across the yard to the shed where we kept our bikes. He threw me up on top of a workbench. He was baying now, not just shouting. You couldn’t understand what he was saying but I know it had to do with my hair and my water drinking and how fucking useless and insolent and pathetic I was, but it wasn’t coherent. It was just pure violent rage, and it was directed at me.

There was a lone bare lightbulb hanging from the shed ceiling. I remember looking up at it as he scrambled in a drawer behind me. Soon my head was propelled forward by his hand, the other one wielding a rusty pair of clippers that he used on the sheep we had in the field in front of our house. They were blunt and dirty and they cut my skin, but my father shaved my head with them, holding me down like an animal.

I was hysterical now, as hysterical as he was, but I knew he enjoyed hearing me scream and it would be over quicker if I was quiet and limp. But that was so hard. I was in pain and shock and I still hadn’t had a drink of water and I felt I was going to pass out with trying to catch my breath. All I could do was wait for the end. Eventually it was over. He pushed my head one way, then the other in order to inspect his work, then threw the clippers back in the drawer.

“You get your hair cut properly! Do you hear me?” he said, rage abating, coming down, spent.

“Yes,” I tried not to whimper.

He whacked me across the back of my head and was gone. The shed door banged, and I was left to climb down from the bench. I made sure to clean up the mess. I gathered in my hands the clumps of my hair that had fallen to the floor and took them to the rubbish bin outside. I returned to the shed once more to make sure everything was back to normal, and then switched off that lone lightbulb and headed back into the house. I heard the sound of my dad’s van heading up the sawmill yard and I stopped for a moment, filled with shock and relief that he was gone.

In the bathroom I drank some water from the tap. Bits of hair fell into the sink as I drank and I could feel droplets of blood on my neck. Finally I stood up and stared at my reflection.

I looked like a concentration camp inmate, and I wanted to die. Really, in that moment I wanted to die. My mum tried to tidy up the mess with scissors, to make it look less uneven, but there were patches that actually had no hair left at all, that couldn’t be disguised. I would have to go to school looking like this. I cried all through the night. The next morning my eyes were so red and puffy they were almost closed, but I was glad because they detracted from my head. I told my teachers I had reached up to a high shelf and knocked over a jar of creosote and some had gone in my eyes. When asked about my hair, I said I had tried to cut it myself.

NOW

I have had more hairstyles than most men of my age have had hot dinners.

It doesn’t take a genius to work out that part of the reason I have so enjoyed changing the colour, length and look of my follicles over the years is something to do with reclaiming the power my father took from me in this regard (as well as many others) as a child. My hair has been blond several times, it has been short and spiky, long and floppy, sleek, shaggy, and everything in between. I’ve even faced the clipper demons and shaved my own head more than once.

It took a while to get to this place, though. In my late teens, there were several occasions when I was in a hair salon and would suddenly feel nauseated, and twice I actually vomited, not realising till many years (and quite a lot of therapy) later that my body was manifesting physically what I could not yet cope with emotionally. I clearly had some deeply suppressed and deeply painful coiffure memory. But after I had left home, and was free from my father’s grip, I began to make my hair a symbol of my own freedom. One time at drama school, in a particularly semiotic act of self-assertion, I actually agreed to my youthful locks being dyed purple by an overzealous hairdressing student and went back to the parental home for the weekend with my head held high and nothing, not a word, was said about it. (I did wear a purple sweater as well, in an attempt to divert all the attention, but still, it was ballsy, don’t you think?!)

I suppose what I am saying is . . . I am okay. I survived my father. We all did—my mother, my brother and me—literally as well as figuratively. But as with all difficult things, it was a process. But more of that later.

THURSDAY 20TH MAY 2010

I am standing on the stage of a huge marquee that houses the Cinema Against AIDS Gala in the gardens of the Hôtel du Cap, just outside Cannes. I am looking out at a sea of rich, tanned, chatty French people, all sipping champagne and gossiping to each other and ignoring me and smoking, smoking, smoking.

I should point out that I am not alone on this stage. I am flanked by Patti Smith and Marion Cotillard, and the three of us are just standing there, and absolutely nothing is happening. Luckily, nobody in the audience is paying any of us any attention at all, and it feels like we are trapped in celebrity aspic.

Suddenly the reverie is broken by a sheepish voice that turns out to be my own, saying into the microphone, “Um, sorry about this delay, ladies and gentlemen, we’re, eh, just waiting for Mary J. Blige to return to the stage so we can auction off a duet with her and Patti.”

Patti Smith’s head whipped round towards me so fast I actually felt a draft. Panic made her eyes seem even more otherworldly than I’d remembered when she’d passed me on her way to the stage earlier in the evening. Right now she was the spitting image of one of those girls in The Crucible, fresh from a hellish vision.

“What?” she spat. “What would we even sing together? No one told me about this!”

You may not know it but Patti Smith is prone to spitting. I first met her at a party in a New York City clothing store a couple of years earlier. She sang a few songs as cute young people in black milled around serving canapés and champagne to less cute older people in black. It wasn’t very rock and roll, but then Patti changed all that. In between two of her songs, she spat. Not an “Oops I’ve got a little something stuck on my tongue” kind of spit, but a great big throat-curdling gob of a spit. A loogie as they say in the Americas. And she spat on the carpet. Several times.

No mention was made of Patti’s spitting by anyone in the store, least of all me, when I was taken to meet her after the performance. As we were introduced I could see Patti sizing me up rather suspiciously with her Dickensian eyes.

“You’re the mystery guy, aren’t you?” she said, pupils widening in recognition.

“What?” I said, a little overwhelmed.

“You’re the guy who hosts Masterpiece on PBS, aren’t you?” she said, as though she herself were one of the TV detectives I did indeed introduce as Masterpiece Mystery host. I was just processing the fact that Patti Smith was an avid viewer of Miss Marple and Co. when she dealt me another body blow:

“I’ve always wanted that job,” she muttered wistfully.

I made a pact with myself right there and then never to tell the Masterpiece people this information, as they would surely bump me and make Patti’s wish come true.

Can you imagine Patti Smith coming out of the shadows in a black suit, spouting forth about Inspector Linley or some malfeasance on the Orient Express and ending each introduction with a resounding gob into a specially designed PBS spittoon? I can. It would be a lot more entertaining than that bloke in a suit with the funny accent they have on now.

Meanwhile, Marion had walked to the side of the stage and was shouting to anyone who would listen, “Do something! Do something!!”

I admired her Gallic sense of injustice, but I knew her cries would be in vain. These kinds of events, though seemingly glamorous and sophisticated from the outside, are often organised with the finesse of a nursery nativity play, and one whose teachers are all lapsed members of Narcotics Anonymous.

Patti and I were left centre stage, both numb. She was presumably running through the list of songs she and Mary J. Blige might both know, which can’t have taken long.

I was thinking back to earlier in the evening. I had started the show with a song (“That’s Life”—how sadly apposite it now seemed) and a monologue in which I was purporting to channel the spirit of Sharon Stone, the event’s usual host and whose shoes I was filling, as it were. Alas, the crowd was underwhelmed. The only time the drone of chat slightly faltered was when I briefly made them think Sharon was watching the proceedings via a webcam from the film set that forbade her presence. “So make sure you bid high,” I had warned. “Cos that bitch will cut you.”

A small crowd had gathered at the side of the stage, some offering advice, others offering their services to fill the embarrassing gap. Suddenly Harvey Weinstein, the movie mogul and the man whose genius idea it had been to auction off the duet between Patti and Mary J. in the first place, came rushing in from a side door and blurted out that he had just been ripped a new one by Ms Blige. A visible and voluble tremor rippled throughout the gaggle of glitterati. Harvey does not get dressed down by anyone, ever, let alone a ferocious R & B legend who was on her way home when she heard her name being announced for a duet she also knew nothing about. Harvey had that detached air of someone who had just been mugged. I had a sudden thought that witnessing his encounter with Mary J. would have made a much better auction item than a duet between the two ladies, but I used my inside voice and kept that to myself. Harvey mopped the sweat from his brow and said that Mary had finally acquiesced and would be out in a moment, presumably when she had finished wiping his blood off her Louboutins.

As Mary, Harvey and Patti returned to the stage, smiling as though they had planned all this years before, I fled the tent and sneaked off to the hotel bar to drown my sorrows. I realised I had never actually liked Cannes. Well, I like Cannes, the actual town. What I’m not so keen on are those few weeks every May when the town is marauded by movie folk.

My first ever Cannes was in 1992, when my debut feature film, Prague, premiered there. Looking back, it was all a giddy blur. The only film festival I had ever been to before then was back home in Scotland, when a film I had made in my last term of drama school, Gillies McKinnon’s Passing Glory, had its premiere at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1986. I remember that experience very vividly because it was the first time I had ever seen myself on the big screen and I was horrified by how my nose seemed to appear at least fifteen seconds before the rest of my face. A less confident man might have avoided the camera for life.

But I soldiered on, and here I was, not strolling up Lothian Road and popping into the Edinburgh Filmhouse, but cruising the Croisette and monter l’escalier of the Palais des Congrès! That week I realised for the first time that glamour actually had a smell. But also I was reminded that the industry I was in was show business.

Film festivals are really just business conventions, you see. It could be photocopiers, it could be shower curtains, Cannes just happens to be movies. And I think any business convention, even such a glamorous one as the Cannes Film Festival, can only be interesting for so long because too many people are talking too much about the same thing: their jobs or product— as not just photocopiers and shower curtains but also films are referred to nowadays. Now don’t get me wrong, I love my job, I love talking about films, but if that’s the only topic of conversation available for days at a time, I get a serious bout of ennui.

That night, in my beautiful room in the Hôtel du Cap that looked out onto the stunning terrace that sloped down to the twinkling Mediterranean where the little dinghies of paparazzi bobbed in the wake, I had funny dreams. I dreamed I was back onstage in the tent and Harvey was auctioning off a kiss with me starting at thirty thousand dollars, and nobody was bidding! The fact that this had actually happened to Ryan Gosling earlier that evening only further fuelled the nightmare.

“No, Harvey,” I kept saying. “Be more realistic. Start at a hundred pounds!”

I also dreamed of my mum, feverishly knitting lots and lots of pairs of socks to give as Christmas presents to all the new Asian relations she was about to acquire.

Yes, I’ll run that by you again. You see, the very next day, I was to fly to London to prepare for the filming of an episode of the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are?, a very popular programme in which celebrities have their genealogy investigated, and studious, balding men in tweed jackets with leather patches on the elbows help the celebs pore over ancient parchments wherein family secrets are hidden. But not for long of course, as a hitherto unpredictable secret is revealed, and then the celeb cries.

I had been asked at the end of the previous year if I would be interested in taking part in the show, and had immediately said yes. Then came the rather unnerving few months when the production company people went off and did some initial research to see whether or not my past was worthy of a full hour-long probe. In other words, they needed to determine whether my ancestors were interesting enough. Being an actor, I am very used to the notion of waiting for people to pass judgement on me—audiences, critics, awards juries, fashion police—all do it with such alarming regularity that it has almost ceased to be alarming. But this was different. This time the judgement was not about me, and yet it reflected on me.

And I wanted very dearly to do this show because it would give me the opportunity to get to the bottom of a mystery in my mum’s side of the family, a mystery whose received explanation I had never fully bought and knew would be resolved by the programme once and for all. And hence the dream about my mum knitting socks for all those new family members I imagined I was going to unearth.

Well, actually, there were two family mysteries. The other one involved my dad’s side, the Cumming clan of Cawdor. Yes, that Cawdor, “Glamis thou art, and Cawdor; and shalt be what thou art promised” and so on. Cawdor is a little village surrounded by forest and farmland in the north of Scotland, and Shakespeare had set Macbeth there without bothering to research the fact that the real Macbeths never set foot in the place because they died three hundred years or so before Cawdor Castle was even built. (This lack of attention to historical detail is more grist to the mill for my theory that Shakespeare, if he were alive today, would be writing for TV. But somewhere classy, though.)

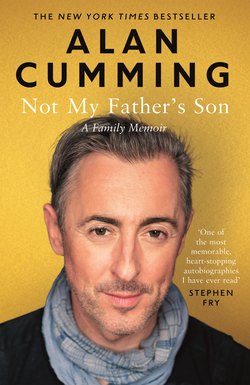

My dad’s family had been Cawdor Estate farmworkers for as far back as anyone could remember. Cut to the 1980s. Like many privately owned Scottish castles, Cawdor’s lairds were feeling the pinch and so opened their home to the public, thus commencing a stream of postcards, sent to me by various friends who had toured the castle, of this portrait . . .

Do you think there might have been a dalliance belowstairs at some point? Perhaps the help gave a little extra? Hello?!

I am startled by the resemblance of this man, John Campbell, the First Lord of Cawdor (painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1778 and hanging in the castle’s drawing room to this day) to myself. I have a postcard of it in my study, and several friends have mistaken it for a still from some period movie I’ve done.

My imagination is pretty vivid and knows no bounds at the best of times, but now it went into overdrive, and I dreamt of future episodes of Who Do You Think You Are? revealing that I was in fact the rightful Earl of Cawdor, and then a special follow-up show detailing the difficulties of trading in my jet-setting Hollywood life for one of a Scottish laird dealing with grumpy American tourists and damp banquet halls.

Of course I knew that aside from going to Cawdor and wrenching a chunk of hair off the present earl’s head for a DNA test—something which was not in the remit of the rather scholarly methods of Who Do You Think You Are?— there would be no way of proving the veracity of my potential claim to minor aristocracy. If some randy laird long ago got a chambermaid up the duff, thereby infusing the Cumming lineage with bluish blood, he would hardly be rushing to the village clerk to have it written in the annals for TV researchers to chance upon centuries later, would he?

No, the real mystery, and the one I was happy to learn that the show was going to focus on, concerned my maternal grandfather, Thomas Darling.

Although my mum, Mary, kept the surname Cumming after her divorce from my father, she is known to me, my brother Tom, and all our friends by her maiden name, Mary Darling. She isn’t Mary, she is Mary Darling. This is mostly because her name so suits her. She is a darling.

I had spoken to her several times that week before I arrived in Cannes, as she had been getting more and more excited about the start of filming. It was her father that the show was going to discuss, after all, a man she last saw when she was eight years old, although he hadn’t died until she was thirteen, five years later, in 1951.

This is what I knew: Tommy Darling was from the north of England, an area known as the Borders for its proximity to Scotland, and was orphaned at age two. He had married my granny and had four children—Mary Darling and her three younger brothers: Tommy, Don, and the now deceased Raymond. He was a decorated soldier in the Second World War. But after the war ended Tommy Darling never came home, ever. He joined the Malayan police force and died there in a shooting accident, and was buried in neighbouring Singapore.

But why had he never returned to his family? And what exactly were the circumstances of this “shooting accident”?

In the run-up to the beginning of filming, my mind raced about the possible outcomes of Tommy Darling’s story, but also about the way a family can have so little knowledge of a relation only one generation away. When little is known and less is spoken about, it’s so easy for glaring inaccuracies to be smoothed over by surmise and assumption. I realised that I had no idea who my granddad was, and neither did my mum or my brother. Mary Darling’s mum, my beloved Granny, had died a few years before, but I never remembered her speaking of him. She had actually remarried after his death, and when her second husband died there was yet more baggage heaped on top of Tommy Darling’s faint shadow.

If Mary Darling was excited, I was agog. I love a surprise, you see. I loved the fact that I would not be told by the production staff where I would be going on this odyssey until the day it actually began, and each day could mean a different country, a different continent even! I had been told only that the first week of the shoot would take place in Europe (pretty vague!) and that I would start in London but would need my passport at some point. I felt like a little boy again, that feeling that I would burst with the waiting and the suspense. And worse, although the show was normally shot in two consecutive weeks, because of my filming schedule the second week and conclusion of the story would not happen for another month. I didn’t know how I was going to manage to contain myself for a whole four weeks! I did know, however, that in two days’ time, on Saturday morning in London, I had an appointment with a doctor to get some required jabs for the second part of the shoot, and after a quick search on the Internet I’d discovered that the countries these inoculations were required for included Singapore, so hey ho, call me Sherlock, I was pretty sure I knew where I was going to end up.

THEN

Memory is so subjective. We all remember in a visceral, emotional way, and so even if we agree on the facts—what was said, what happened where and when—what we take away and store from a moment, what we feel about it, can vary radically.

I really wanted to show that it wasn’t all bad in my family. I tried so hard to think of happy times we all had together, times when we had fun, when we laughed. In the interests of balance, I even wanted to be able to describe some instances of kindness and tenderness involving us all. But I just couldn’t.

I spoke to my brother about this. He drew a blank too.

We remember happy times with our mum. Safe, quiet times. But as a whole family? Honestly there is not one memory from our childhoods that is not clouded by fear or humiliation or pain. And that’s not to say that moments of happiness did not exist, it’s just that cumulatively they have been erased by the dominant feelings that colour all of our childhood recollections.

I can remember us all in a Chinese restaurant in a nearby town. We hardly ever ate out together so when we did it was a memorable occasion. But there is something nagging too, about my memories of that place, something that jabs at my heart when I think of it. I know that at least once in the few times we went there as a family I must have been hit for some flaw my father perceived, must have tried to hide my tears and humiliation from other diners. We surely had some meals there that were free of his mood swings and his tongue and the back of his hand, but they don’t stand out for me.

I can remember when I was very little in the living room at Panmure, at least four or five years old, playing horsey with my father. I see him balancing me on the foot of his crossed leg as he watched TV, and him bouncing me up and down to my squeals of delight. I remember being genuinely filled with joy in those moments. But as soon as a memory like that settles for too long in my mind, another, darker one forces it to slide to the side.

I see a freezing wintry afternoon in the sawmill yard. I am on the red bike I was given for Christmas and my father has decided that today is the day that I must ride it without stabilisers. To this moment, I have never once tried to ride without them. There is ice and snow on the ground and I see my father taking the stabilisers off and pushing me down the driveway, too fast. Every time he does so I panic and fall off, and soon he gets frustrated with my failure and pulls my trousers down and slaps me really hard on my bare bum. It is so cold I have no feeling in my toes, and barely in my fingers; it is sore for me to sit down on the seat, I am scared, I am crying, and yet somehow my father thinks I am going to be able to achieve what he has decided I must do. Each time I fall, despite my pleas and promises that I will practise and be able to ride without the stabilisers soon, I am bent over his knee, feel the blast of freezing air around my genitals, and then severe, painful slaps to my behind.

I don’t remember how it ended. What I do remember is my mum washing me and getting me ready for bed in front of the living room fire later that night, and her gasping as she saw the ring of blue, black, and purple bruises that had appeared. My father came in to say good-bye before he went out for the night, and my mother admonished him for his handiwork.

“He’s all right,” he said, running a comb through his hair as he looked in the mirror.

“You’ve gone too far, Ali,” my mum replied as he disappeared out the door.

Aside from visits to family, our holidays together were mostly to caravan parks in seaside towns in other parts of Scotland. I remember when I was about seven we went to Dunbar on the southeast coast and I got to play on the go-karts.

This is a photo of me, beaming in my shorts and crew cut, looking towards my mother and my father, who most likely took the picture. So it’s not that every second of my childhood was filled with doom. But every second was filled with the possibility that in an instant my father’s mood would plunge into irrationality, rage and ultimately violence. This very feeling, this possibility, is what darkens the part of my mind where my childhood stories live.

It’s hard to explain how much that feeling of the bottom potentially falling out at any moment takes its toll. It makes you anxious, of course, and constant anxiety is impossible for the body to handle. So you develop a coping mechanism, and for us that meant shutting down.

Everything we liked or wanted or felt joy in had to be hidden or suppressed. I’m sad to say that this method works. If you don’t give as much credence or value to whatever it is that you love, it hurts less when it is inevitably taken from you.

I had to pretend I had no joy. It will come as a shock to people who know me now, but being able to express joy was something it took me a long time to be confident enough to do. I’ve certainly made up for it since, and for this, I am proud and grateful.

Like any tyrant, my father was an expert at knowing how to hurt you most effectively and quickly. If Tom or I became too keen on any hobby or person, our father would ensure that they were removed from our lives instantly. Tom was a great football player, and played for a local boys’ club. Eventually he began to receive interest from a professional team’s scouts. Immediately our father banned him from attending the football club altogether. I had a friend from school who lived in a local village, an arty girl who played the harp and whose parents were doctors. My father became convinced, based upon nothing more than a look in her eyes, that she was a drug addict, and I was never allowed to see her again. Both instances, I realise now, screamed of my father’s insecurities—of me mixing with educated people whom he felt he could not relate to, and of Tom succeeding in a field in which our father himself once had aspirations.

His actual violence towards us rarely lasted beyond one or two really hard whacks, the odd kick. I actually think the prolonged period of tension before landing his blows, as we were systematically inspected, chided and humiliated, had a far worse effect than the actual hits. This certainly contributed more to our need to shut down, as we all learned early that the best way to cope in that time when his ire was building and his cruelty unfurling was to give nothing away, to try and become nothing, the nothing he both thought of us and wanted us to remain.

But looking back from the vantage point of adulthood, I see that there was a definite sea change in my father’s behaviour.

I think I was about eight or nine. Something transformed in him. He had always been prone to outbursts of rage, but now a darkness descended upon him that meant the glimmers of light between the outbursts disappeared. It was as though my father was deeply depressed, and now I think perhaps he was. He obviously did not want to be in his marriage, he seemed to be perpetually irritated by the existence of his children, and nothing ever seemed to please him. Indeed, the only signal we got that something did not displease him was his silence, his inertia.

Now began what I remember as a time of constant darkness, silence and fear. Being around him was like navigating a minefield. We could never relax. We were never safe. He began to go out every night. I remember sitting in the living room with my mum, hearing him getting ready upstairs. Eventually the door would open and his head would appear.

“That’s me away!”

But he would be gone before the words had left his mouth, his eyes not even seeing us. It was like he was saying good-night to a pet, and eventually he stopped saying it altogether.

I didn’t understand what had happened, but of course I assumed it must have been something I had done. I was always being told by him how much of a disappointment I was, both in my appearance—my hair, of course, but also my posture, my weight, my nose, my moles—as well as my inability to perform the simplest of tasks, though his lack of detail in explaining what he wanted me to do or the physical enormity of what was entailed guaranteed I would fail. Once he actually demanded I drive a tractor, though I had never done so before nor had any coaching on how to do so by him or anyone else. I tried to reason with him. Often he gave me tasks that were huge and would take till nightfall and beyond, but this was another level. Now he was asking me to actually endanger my life by operating heavy machinery and I became very, very scared. My father began to shout at me and I knew I had to meet his demand. I clambered up on the high seat. My feet didn’t even reach the pedals. Of course I made a mess of it and the tractor lurched into a hedge and stalled. I was hit, and perhaps that was the first time I was relieved by the violence, because it meant the conclusion of an impossibly difficult and stressful experience.

One night, as he popped his head round the door and lobbed his customary “That’s me away”, I asked him, “Where are you going?”

My mum looked up from her knitting; my father stopped in his tracks. There was no malice in what I had asked. I was genuinely curious. But nobody ever questioned my father, and I could see I was on stony ground.

“D’you want to come with me?” my father replied, defensively.

“But where are you going?” I asked again.

“You tell me if you want to come and I’ll tell you where I’m going.”

I considered this for a moment. I knew my father was going out. He was dressed up a bit and he smelled of Old Spice and his hair was Brylcreemed. If he was going to the pub I wouldn’t be allowed in and would have to spend the evening in his van, something I did not want. But I sensed that perhaps there was more to it than that, and I think my parents could tell.

My mum said nothing.

“So are you coming or not?” my father said after a few moments, knowing he had won.

“No,” I replied, meekly.

I can’t remember how I came to know, whether it was kids gossiping at school or something I overheard at home, but soon I understood that the change in my father’s behaviour was because he was seeing another woman, and that Tom and I were a constant reminder of the life that trapped him.

Soon after, one sunny Sunday afternoon, we all went to the beach at Carnoustie. As I’ve said, it was rare we did anything together, let alone anything as carefree and exciting as a trip to the seaside. Summers are short in Scotland and we tend to take advantage of the slightest hint of sun, and that day was no exception. Every time the sun peeped out from behind the clouds we raced over the sand into the freezing North Sea, ducking under the waves for a few moments before rushing back up the beach again to the shelter of our striped windbreak, an essential component of any Scottish beach excursion.

My mum opened the Tupperware box of sandwiches she’d made and we tucked in. Just then, a woman and her son appeared. We knew them locally and they greeted my father very cordially, but I could see that the woman avoided my mother’s eyes. They were invited to sit down and eat with us and they did so. Conversation was stilted, and I did my boyish best to smooth things along. But I knew. This woman was having an affair with my father. That’s why we had taken this rare family outing to the beach. And not only did he have the audacity to arrange this encounter and walk them to their car, leaving Mum and me to finish our sandwiches in shameful silence, but when he came back he pretended that their appearance was a total coincidence. Even worse, he actually documented that sad day, that day when he stepped over the line of respect and made us complicit witnesses to his transgression, by taking this photograph.

FRIDAY 21ST MAY 2010, NOON

By next lunchtime I had left Cannes and was back in Nice airport, slurping down a Bloody Mary (a mandatory pre-flight ritual for me) and checking out the reports of the previous night’s event online. I was happily shocked to read that, although not very forthcoming with their attention, the audience certainly coughed up the cash, as seven million dollars had been raised for AIDS research! Patti and Mary J. must have nailed it.

Mary Darling had left another message earlier that morning. She told me there had been a reporter from the Sunday Mail at her door. This wasn’t unusual. Over the years my mum had encountered several tabloid reporters on her doorstep, trying to get a comment from her about something (or someone!) I had been rumoured to have done or said. Now she was quite an old hand at it. She said that this time the reporter was asking about my father, wanting to find out where he lived so they could ask him for a comment about something I had said in a recent interview for The Times.

My father had been estranged from his family for many years by this point. The British press, particularly the Scottish branch, was fascinated by this estrangement from his celebrity son and had made several attempts over the decades to goad Mr Cumming senior into “having his say” about his lack of relationship with me. This was the usual pattern: a quote from an article I’d done for some other publication would be pounced and elaborated on, and then a suitably hysterical reaction quote would be sought, encouraged or fabricated.

I knew immediately which comments from the Times piece they would have latched on to. I had done an interview in support of The Good Wife, the television show I had recently joined the cast of, originally planned as a feature in the Relationships and Health supplement of the paper. During the course of a very wide-ranging and honest chat, the reporter had asked if it saddened me that I had no relationship with my father.

“Of course,” I had said. “It’s the saddest thing in my life.” And it was. I explained a little of how my brother and I were still waiting for our father to take up our offer to continue a relationship with us.

But I went on to talk of my belief that the way things were now was preferable to the situation that had existed previously, and that my mother and my brother and I were happier now than when there had been contact with my father, and presumably he was happier too.

I’d said this many times before. It was true, but it was also my way of moving the conversation away from “Alan’s pain” and into a more sanguine and healthy admittance that sometimes people do you a favour when they drop out of your life.

And when the discussion turned to health, and I was asked about family illness, I told the reporter that recently when I’d had my first physical with a new doctor he’d asked if cancer ran in my immediate family, and I realised that, as I’d had so little contact with my father as an adult, I didn’t know. I actually knew nothing about him or his health. Then, out of the blue, in the spring of 2010, my father contacted my brother Tom to tell him he was battling cancer, and Tom and I suddenly discovered which strain of that disease’s odds were genetically stacked against us.

As we were finishing, the reporter asked if I thought I would ever see my father again. I said I had thought about this a lot and imagined that the only way we might have any contact would be if he reached out as he was dying.

However, the in-depth interview was scrapped in favour of one of those shorter, pithier “What I’ve Learned” pieces, and a collection of my words was assembled randomly under topic headings that bore little relation to the context in which they were uttered.

“My life is so much better now that my father is not in it. He does have cancer, which apparently runs in the family. Maybe next time I see him he’ll be really ill, or he’ll be dying and I may not see him” is how the Times mash-up ran.

No wonder the Sunday Mail was sniffing about.

Every person in the public eye will have stories of media invasion and misrepresentation. As, sadly, there were no classes at drama school for dealing with these sorts of things, I, like many before me, fumbled my way through the years and finally developed my own way of coping with this part of my job (and my life), mostly by trying to be open and honest. I had tried to be guarded about parts of my personal life in the past, but realised the hard way that doing so came over as coyness and invited speculation.

In 1999 the News of the World, the most vicious of tabloids in both its disdain for facts and its methods of accruing them, ran a story implying that I was accusing my father of sexually abusing me as a child. This was completely false. I had done no such thing, nor had my father.

But again, a comment I’d made about the aftermath of playing Hamlet, in an interview with the American magazine Out a few months prior, had been seized upon, misquoted, sensationalised, and then deemed irrefutable evidence of an accusation of sexual molestation.

Here’s what I actually said:

After Hamlet I just suddenly changed my life. I was not divorced but separated, and I also confronted my dad, with my brother’s help. We went and talked to my father about the things he’d done to us in our childhood. Hamlet was probably not totally the cause of that, but it unlocked boxes in my mind that were locked away in the attic. And they all came out and I had to deal with them. It caused a lot of pain to many people, including myself.

The next day, the Daily Record, sister paper to the Sunday Mail, ran a story with the headline “Father of Bisexual Star Alan Hits Back” in which my father angrily denied my nonexistent accusations.

As you might imagine, all hell broke loose.

I was in New York at the time, about to attend the premiere of a film I was in—a remake of Annie (talk about the universe throwing you a curveball!)— when I got a call from Mary Darling, who’d just had her irate ex-husband on the phone. He was understandably furious: every single person he knew would have seen the story. It transpired that the News of the World had been camped outside his house, and now other publications were ringing his doorbell.

I felt sick. My father had terrorised me, Tom and Mary Darling throughout our lives, and was physically, mentally and emotionally abusive but he was no sexual molester. I was horrified. But my horror was not just about how awful it must be for my father to be falsely accused of such a terrible act, but also that his rage was, right now, directed once more at me. The same fear and anxiety I had lived with as a child suddenly reconsumed my life. I could hear it in my voice as I spoke to my mother. I could hear it in hers. I could feel it within myself.

But worst of all was the fact that my father might think I actually had accused him of these things. My father did not really know me. He had no way of contacting me, as we hadn’t spoken in years at that point. He also had no experience of dealing with the press or understanding of their disregard for reason in pursuit of a scandal.

In New York City, Cumming junior was smiling for the cameras in an Alexander McQueen ensemble between frantic phone calls to see what could be done to calm his father, comfort his mother, take the tabloids to task, and demand an apology for this libel. Cumming senior, at home in Scotland, also did what he felt was right: he talked. To his credit he said he didn’t want to carry on a conversation with his son via the pages of a national newspaper, but of course he was saying that in the pages of a national newspaper.

Eventually I was able to secure an apology from the Daily Record. My publicist had told me that there was no way I could take on the News of the World, which had a renowned huge legal fund purely for quashing lawsuits from the aggrieved subjects of its stories, as well as the knowledge that anyone who wanted to pursue them had to countenance an already painful story being raked through the papers all over again should they go to court.

And although the few contrite lines at the bottom of the Daily Record’s Letters page a few weeks later were a far cry from the screaming headlines of the original story, it was important to me for my father to know I had done all I could to right the wrong. I wanted to show him that I cared about such an intrusion to his private life, that I was doing what I could to protect him.

Of course at the same time I was reminded that my father had never shown those kindnesses towards me, and I wondered how different such an intrusion would have felt if he had known immediately that he could pick up the phone, tell me there were reporters outside his door, and hear my advice and my reassuring words.

So now, back in the lounge at Nice airport, I listened to Mary Darling’s lilting Highland tones and knew what to expect. Probably a gossipy, needling piece in that Sunday’s Mail, no big deal compared with what had come before, but able to churn up old sadness nonetheless.

“But don’t you worry, pet,” she said reassuringly. “I just said I couldn’t help them, had no comment, and smiled and shut the door.”

My flight to London was called. I took a last sip of my Bloody Mary and thought to myself, “Tomorrow’s chip paper!” And it was true: by Monday lunchtime the Sunday Mail would be used for wrapping up greasy bags of chips in fish-and-chip shops all over Scotland.

But by then, the damage would have been done. So much more damage than I could ever have countenanced.

We ascended into a cloudless Mediterranean sky and, as I always tend to do when airborne, I smelled the roses. Maybe it’s the fact that I hurtle through the sky in a metal-fatigued box so regularly and therefore the odds of said box careering to a watery grave must be quite scarily higher than for the average traveller that makes me count my blessings in this way. Or maybe it’s the copious amounts of free booze. Whatever, it’s another inexorable ritual.

But I smell the roses not just to remind myself of how lucky I am, but also to wonder how on earth it all happened. I smell the roses to try and figure out how I came to be in the garden at all.

THEN

Nobody disliked the rain more than my father. All of a sudden nature would not bend to his will, time would not mould to his form. His meticulous plans would have to be altered. Men would have to be redirected to new, hastily created tasks. The rain brought chaos to his carefully constructed realm. And on this particular day, I would become the unwilling, and as usual ill-informed, brunt of his frustration.

This day was the first time I truly believed I was going to die. I looked into my father’s eyes and I could see that in the next few moments, I might leave the planet. I was used to rage, I was used to volatility and violence, but here was something that transcended all that I had encountered from him before. This was a man who had nothing to lose. The very elements were raging against him, and what was one puny little son’s worth in the grand scheme of things? I felt like I was my father’s sacrifice to the gods, a wide-eyed, bleating lamb that he was doing a favour in putting out of its misery.

It was during my summer holidays from secondary school. I was old enough to be working for him full time by then, but not yet fully grown enough to be sent to aid the men with their tasks. So not only was I feeble and weak and inept, I also, in this current downpour, demanded more time and planning and attention due to my inadequacies. It was always like this with the rain. I longed for it as respite from the backbreaking labour, but as soon as it came, I knew I was doomed.

We had been working outside in the nursery, separating the one-and two-year-old spruce saplings that were strong enough to be taken to the forests and planted from the runts of the litter. These, much like me, needed to be cast aside. The rain had necessitated that this work be postponed, and instead all the saplings were transported into the old tractor shed in the sawmill yard, where they could be graded and selected in a dry place. This, I was told, was to be my job. I was sent to the shed to await further instructions.

There was a single bare lightbulb hanging above me. I stood beneath it, surrounded by mounds and mounds of spruce saplings, hearing my father’s voice come wafting through the gale as he ordered his men around.

Finally the shed door opened and a gust of wind and a clap of thunder heralded his entrance. In the lightbulb’s dim hue, his lumbering frame cast a shadow over me and much of the piles of baby trees. I remember the smell of them, so sweet, fresh and moist.

“You go through these,” he said, picking up a handful of saplings, “and you throw away the ones like this . . .”

He thrust out a hand to me, but it was full of saplings of various lengths and thicknesses. With his shadow looming over me I could barely discern the differences between any of them.

“And you put the good ones into a pile over here.” He gestured to his right.

I looked up at him, blinking and windswept.

“How do I know if they’re good or not?” I asked.

“Use your common fucking sense,” he said from the shadows. A second later a shaft of eerie grey-blue light filled the shed, thunder vibrated beneath my feet, and he was gone.

For the next few hours I sifted through the trees like a mole, blinking and wincing in the semi-darkness. After a while the saplings began to blur into a prickly procession, spilling through my fingers. I would check myself and go back through the discarded pile at my feet and wonder if I had been too harsh in my judgement. The pile of rejected saplings seemed to be bigger than the successful ones, and I questioned if my criteria were too harsh. Then pragmatism would win over and I’d tell myself I needed to be ruthless, that this pile had to be shifted and it never would be by prevaricating or becoming sentimental.

Of course my father had not given me much to go on to make my choices. He was usually vague and generalised in his instructions, but incredibly specific when it came time to inspect my work. But today was different. Perhaps because he was so preoccupied with the challenges the weather had created for him and his workers, he had doled out fewer instructions than usual about how I was to proceed. For instance he gave no indication of what ratio of plants should be kept to those that should be rejected. He gave no clues as to the criteria I should use in filtering them, aside from that shadowy fist he had thrust in my face. I was standing in a freezing, damp, dark room surrounded by thousands of baby trees. I began to panic.

I did what I could. When my hands began to get numb I pushed them between my thighs and held my legs close together to bring some life back into them. At times I felt I was on a roll, but then the panic would set in. I would glance down at a mound of discarded trees and realise I had been too hasty in my judgement. They seemed too healthy, too thick, too tall. But I couldn’t save them all, could I?

Every moment of doubt was compounded by the knowledge that I was wasting precious time and before long my father would return. And of course, he did.

I heard him saying good-night to some of his men, and my heart sank. With none of them around, he would have less motivation to rein in his fury. After a while I heard his footsteps and the door opened slowly. He stood for a second, silhouetted, dripping and silent, as though this was how he wanted me to remember him.

I stood up from the bundles of plants and tried to ease back into the shadows.

My father bent down to one of the piles I had made and without looking up at me asked, “What are these?”

“Rejects,” I said, questioningly.

He sifted through them for a moment and then, without warning, he backhanded me across the face. I flew through the air and landed in a heap against the stone wall of the shed. I was breathless and dizzy, the wind knocked out of me. I knew I had to get away. I began to run for the door, but my father grabbed on to my collar with one hand and smashed my mouth with his other. I fell to the ground and instinct told me to stay there. I could tell he had only started.

“What the fuck do you call this?” he railed.

The storm raged outside and it was as though my father was determined to belittle nature with his own wrath.

I could only whimper, “I’m sorry.” I didn’t know what I was sorry for. I didn’t know what he wanted, I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. All I knew was that a line had been crossed. My face was throbbing and the back of my head hurt from where it had landed against the stone wall.

I was on my knees before him and he was throwing plants on me, kicking me and screaming at me. I had apparently rejected perfectly good saplings and at the same time retained puny ones that should have been destroyed. There was no rhyme or reason. All I could do was hope it would be over soon, but he continued to spew insult and bile and his body at me while the crash of the storm covered the sound.

Suddenly there were spikes in my eye and I realised he had kicked me into a pile of saplings, and then I felt the dull thud of his boot against my tailbone and my mouth was full of them too. I wanted to stay there, facedown, curled into a foetal position, and let him finish me off. But the overpowering survival instinct took over, and before he could strike again I turned round and fell to my knees before him, sobbing and beseeching.

“I’m sorry! I’m sorry! I didn’t know! You didn’t tell me!”

I felt pathetic but it stopped him in his tracks.

“I didn’t do it on purpose. I wanted to get it right, but you didn’t tell me. I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. I’m so sorry. Please!”

I was done. Nobody was coming to save me, and nobody cared.

My body began to shudder and heave with such black grief that it surprised even me.

The sound of the shed door banging shut opened my eyes. He was gone. After a while I stopped crying. There were little trees stuck to my hair and in my mouth. My face was throbbing from his blows and my bum hurt from his boot.

In the eaves of the attic room of the shed was a wooden hutch my father had built to house a pair of doves we had once been given years before. For some reason I wanted to go up there. I climbed the stairs and dropped to my knees, staring plaintively into the dark recesses of the empty coop. Time passed. The storm finally subsided. The numbness in my cheek ebbed into a swelling. Darkness fell. Still I sat in a heap in front of the empty birdcage, tears flowing.

I had thought earlier I might die. Now, once again, I wanted to.

FRIDAY 21ST MAY 2010, 5 P.M.

In no time at all I was in my London flat, having a laugh with friends.

I was to be based there for the first week of shooting of Who Do You Think You Are? aside from the mystery trips I would be taking elsewhere. My old friends Sue and Dom were there to greet me and I looked forward to catching up and having a laugh about the insanity of the night before in Cannes, each anecdote more sweet in its telling because it was now just that, an anecdote, and not real life.

I could relate the palpable drama after the auctioneer told Jennifer Lopez her dress made her look like an ostrich, but not have to see it, or feel it. There would be no anxiety that the name of the celebrity I was about to announce would not be the same as the one who walked onstage. There would be no celebrities at all, in fact. Just me and my besties.

Sue and I had met many years ago at the Donmar Warehouse theatre in London. I was there playing Hamlet, immediately followed by my turn as the Emcee in Cabaret that later transferred to Broadway, and we had been best friends ever since. When people ask how we met, Sue likes to tell them she washed my undies, and indeed she did, for then she was a member of that most noble of professions, the theatre dresser. She was also, and is, totally gorgeous. Quite literally, actually. Her surname had originally been Gore, but she changed it legally to Gorgeous, after years of it being her unofficial monicker. The actual document she had to sign to complete the name-changing process was hilarious, asking her to solemnly swear to renounce the name Gore and to be, from that day forth, forever Gorgeous. And she has been. When she married Dom, I and our other bestie, Andrew, were male bridesmaids, stifling our giggles as Sue walked down the aisle to Elvis singing “It’s Now Or Never”.

As the wine flowed and the laughter rose, I felt the feeling I most enjoyed—home. Then, Sue’s phone rang.

“Hi Tom,” she said. “Oh, he’s here. He arrived about an hour ago.” I wondered why my big brother would call Sue and not me to find out my whereabouts. Sue passed me her phone, and immediately I knew something was wrong.

“How are you doing?” Tom asked, a little shaky. Obviously he hadn’t intended to speak to me.

“I’m good. How are you?” I replied, cautiously.

“When am I going to see you then?”

“Tomorrow night, remember? We’re all having dinner,” I said, referring to the plan for him, his wife, Sonja, a bunch of my London friends, and me to meet up in my favourite Chinese restaurant the next evening.

“I really need to talk to you, Alan.”

There was silence for a moment. I tried to process what this meant.

“Well, why don’t you come up a bit early tomorrow and have a drink with me at the flat before dinner?” I said eventually.

“No, I need to talk to you sooner than that.” Tom was trying to hold it together, but the cracks were beginning to show.

“Tom, what’s wrong?”

“I can’t tell you on the phone, Alan.”

“Is it your health?” My mind immediately raced to the worst possible scenarios. My brother is a rock. If he acted like this, it meant there was really something badly wrong. “Has something happened between you and Sonja?”

“No, no.”

I could hear Tom, even in the midst of whatever painful thing he was dealing with, trying to reassure me. It was what he always had done for me.

“Is something wrong with Mum?” But I’d spoken to Mary Darling several times that week and had listened to a message from her just that day. There was no way she could have hidden anything bad from me.

Suddenly, I remembered what Mary Darling had said about the reporter. “Is it something to do with that Sunday Mail guy looking for Dad?”

“It’s all come to a head, Alan,” was Tom’s response. “I need to talk to you tonight.”

It took Tom three hours to get to me. He lives in Southampton and had to catch a train, and what with travel to and from the stations, I had to endure three whole hours of my mind racing and my heart thumping. Sue and Dom tried to distract me, but I could never wander far from the worry. What could possibly be making my brother so upset that he couldn’t even utter it to me on the phone? I was a mess. My mind went to very dark places. The press being involved was a particularly disturbing element.

If I had had the ability at that moment to be rational, I would have realised that there was nothing particularly scandalous about my life that had not been revealed or touched on before now, and I might have taken solace from this added boon of having become an open book. But I was finding it hard to see solace anywhere. I started to get wheezy. I have asthma and one of the times it comes on is during moments of great stress. Sue is luckily a self-confessed hypochondriac and an expert on all homeopathic remedies, so before too long I had a mouthful of pills to distract me. But still the nagging anxiety persisted, and still Tom hadn’t arrived. He kept texting: I’m on the train . . . I’m nearly at Waterloo . . . I’m getting in a taxi.

I kept replaying our phone conversation. Had my father died? Was it something to do with my husband, Grant? He was heading home to NYC now, could something have happened to him? But still at the root of it all was the reporter from the Sunday Mail and the fact that, as Tom had said, it had all come to a head. But what did that mean?

By the time he arrived I felt I had aged ten years. He entered the flat looking remarkably normal. No tears, no visible signs of torment. If anything he looked a little sheepish, as if he were embarrassed by all the fuss he must have known he’d caused by losing it on the phone. For a moment my heart leapt and I thought that maybe this revelation, whatever it might be, was not going to be as portentous and damaging as I’d feared. There were a few awkward moments of small talk and then he looked at me.

“Shall we go upstairs?”

THEN

When I was little, I was bullied by an older boy named David, on the school bus. David’s dad was the head joiner on the estate where ours was the head forester. Tom, six years older than me and a year older than David, had graduated to secondary school by then, and we went our separate ways each morning. Tom went to Carnoustie and the swanky new secondary school, while I went to Monikie and the tiny Victorian stone primary school where there were only six people in my class. The bus I rode looked like something left over from the Second World War, and indeed it was. It was a big, hulking, dark blue military-transport type of thing, with two long benches that faced one another across a vast stretch of floor. The thing about that layout of course was that you could never look away from anyone. Everyone saw everyone else and everything that went on, all the time.

Every afternoon on the way home, and some mornings, I was kicked and pushed and slapped off the seat, my ears twisted back and forth, my books flung around and trodden on, the straps of my schoolbag held so I couldn’t get away, and all the while, through my cries of pain and fear, his taunts that I had no big brother now to protect me were ringing in my (red and sore) ears. Luckily the journey back to the estate gates was a short one, and as soon as the bus stopped I leapt off and made a terrified bolt down the drive, much to the amusement of my tormentor and his little brothers.

It was all very Lord of the Flies, and I was Piggy.

David was a nice enough boy, and I realise now that his bullying of me that summer was just his way of establishing the new world order of the Monikie school bus. My brother had been the undisputed leader till he had ascended to secondary school, and so by terrorising me, David was not only defining himself as alpha male, but also as the new Tom Cumming. How better to show that your former leader’s power is nought than by making his little brother cry?

But then I was mad as hell and I was not going to take it any more. I told Tom. Nothing much was said. Just a tearful confession after he asked me if everything was going okay at school without him. I almost forgot about it until one night we were cycling home from Cub Scouts. David and his siblings were in a gaggle ahead of us. Tom shouted out to David to wait up, and then told me to carry on home.

“What are you going to do?” I asked, suddenly alarmed.

“Just go home, Alan. I’ll be there in a wee while.”

I did as I was told, pedalling fast and whizzing through the estate gates and down the driveway, through the sawmill yard to our house and into the bike shed. My heart was racing; my mind a whirl of what awful torture or bloodshed might be taking place at that very moment on my behalf. My parents didn’t seem to pick up on my nervousness. My mum looked up from her ironing and asked where Tom was when I entered the living room, and my dad kept his gaze on the TV. Minutes later Tom arrived, cool as a cucumber, and gave me a stony look that I knew meant we must never speak of this again.

Five minutes later, the doorbell rang and I raced out to answer it, my heart now in my mouth. I opened the door to find David, weeping and clutching his already bruising eye, being held up by his irate mum.

“Get your father!!” David’s mum yelled.

My father ushered them in. Suddenly out of nowhere our living room was a courtroom, and I was both the smoking gun and the cause of the crime.

“Your son gave my son a black eye,” David’s mum shouted.

“Well, Tommy, is this true?” our father yelled, even though I could tell he was secretly proud.

“Yes, it is!” Tom said, pulling himself up and embracing his sins. “But David’s been bullying Alan on the school bus for months now.”

Everything stopped. David’s teenage shame was now exposed for everyone to see. I felt so sorry for him, this skinny adolescent who had shoved me off my seat and thrown my books around and held me down and whacked me countless times. He had never made me feel as mortified as I knew he now felt.

Suddenly I was shaken from my sympathetic reverie by the realisation that the adults had stopped shouting, David had stopped crying. In fact the whole room had stopped and was now looking at me, waiting for me to bring the whole sorry mess to some sort of conclusion.

“Well, Alan,” my dad said. “Is this true?”

The room fell quiet. I could feel my cheeks burning and everyone’s eyes boring deep, laserlike into mine.

“No,” I said meekly.

Much as I wanted to defend Tom’s tribal quid pro quo, I also felt so sorry for David, snivelling away, the bruise around his eye colouring darker by the second. It was just too much to deal with, and I chose what I thought was the lesser of two evils. As soon as I’d denied he was my tormentor I’d burst into tears, and the adults mercifully realised they were putting a nine-year-old under too much duress, especially when there came no protestation of innocence from David. The Clarks went home, I was comforted, and the matter was never mentioned again. In some way there was an agreement between us all that justice had been served. An eye for an eye. Or more like a black eye for a series of bruises and stinging ears.

I told this story at my brother’s wedding. (His third, incidentally. We Cumming boys love a wedding.) For me it is emblematic of our relationship: Tom always the protective big brother, me in awe of the enormity of his devotion and screwing things up.

FRIDAY 21ST MAY 2010, 8 P.M.

Almost forty years later, Tom is sitting across the table from me on the roof terrace of my flat, visibly shaking and seemingly incapable of beginning the speech that he knows is going to blow my world apart. He stammers and makes several false starts. I beg him to just say it. To just tell me. I am going mad with the waiting.

At first he apologises because he has already told Grant. Again I can’t process what that means. He says he didn’t know how best to tell me and so he called Grant for advice. Everything was whirring—my thoughts, Tom’s voice, the skyline of Soho all around us. He finally manages to get out that our father had called him ten days ago.

“What did he say?” I whispered. I was shaking. I had started to cry. I was in hell. “Please Tom, please . . .”

Tom looked up at me, his blue eyes filled with tears too. He gulped, and finally he said it.

“He told me to tell you that you’re not his son.”

I learned something about myself that night, something I had no idea about. And about a month later, one sweaty afternoon on a terrace in southern Malaysia, I was reminded of it again: when I get really shocking news, my entire body tries to get the hell away as quickly as possible.

Before I had really processed what Tom had said I found myself propelling backwards, knocking over the bench I was sitting on and careening away from my brother. It felt as though I needed to push this incredible information back, give myself the space necessary to even contemplate contemplating it. Downstairs, Sue and Dom thought the sound they were hearing was Tom and me fighting, and that a body had just been flung to the floor.

“What do you mean?” I kept asking.

Tom was holding me now, trying to calm me down. This information was so far from left field it was not even in the field. To say it was the last thing I expected to hear was an understatement of an understatement.

“You’re not his son,” he said again.

Tom was crying too now, but he could see how overwhelmed I was, how much I needed more information, and fast.

“He called me a week ago, weeping . . . ,” he began.

“Dad called you . . . Dad called you weeping?!” I spluttered. Nothing was making sense.

“Yes. He said he was never going to tell you, and was just going to leave you a letter in his will. But he knew you were doing the television show and so he wanted to tell you to stop you being embarrassed in public by finding out that way,” he went on.

Tom was rubbing tears away with his thumb. I suddenly felt so sorry for him. He was still the big brother, my protector. And here we were once again, weeping and scared and clinging to each other. I thought our father had no power over us any more. I was wrong.

“Find out what, Tom?! Please try and tell me quickly. I’m scared. My heart is beating so fast. I think I’m going to have a heart attack.”

Indeed, my heart was pounding so hard I felt the need to clutch both hands to my chest, just to make sure it stayed inside my body.

“You’re in shock,” Tom said. “Take deep breaths.”

He continued. “He called me again this Thursday, and apologised for being so hysterical on the phone the first time. He said he’s on a lot of painkillers for his cancer and he thinks he must have overdone it. But he wanted to assure me, well, to assure you, that it was all true, and he was going to leave you a letter telling you everything in his will, but he wants you to know now and he says if you ask Mum she’ll deny it, but he’s willing to take a DNA test . . .”

“Who is my father then?” I sobbed. “Who is he?!”

Tom said a name. It was not someone I knew, but a name I remembered as a family friend from long ago—from, in fact, the time and the place we lived when I was born. Just hearing that name made everything a bit less abstract. Its familiarity grounded me, and I began to calm down. My breathing became more regulated, my pulse slowed. This was real. It wasn’t just a joke to hurt or scare me, like so many of my father’s edicts from the past. It was real.

“What else did he say?”

“He said that he and Mum were at a dance at the Birnam Hotel in Dunkeld. Mum was gone for a while and this guy’s wife said he was gone too, and Dad and the wife both started looking for them. They went all over the bar and the dance floor and then they went through into the hotel and they saw them, Mum and the guy, coming out of a bedroom together.”

“And then what?”

“And then nine months later you were born,” he added, like he was telling me a really fucked-up bedtime story.

I couldn’t quite believe that my father wasn’t doing this just to hurt me. One last hurrah, if you will, before he died. And the timing of it! How could he possibly think that Who Do You Think You Are? would focus on something so sensational and upsetting and undocumented? And then I remembered my father’s experience of dealing with the media, and it made total sense. Was he actually trying to protect me for once? Of course, I also reasoned, he would also be protecting himself. His cuckolding going public would dent the ego of a man like him immeasurably.

I was not my father’s son.

It wasn’t supposed to have happened like this at all. Tom had discussed it with Grant, and they both felt that I should be told when I was home in New York, with Grant by my side. Tom planned to fly over in a couple of weeks once I had returned from filming in South Africa and tell me in as calm and protected an environment as possible. Poor Grant, therefore, had known this secret for the last few days we were in Cannes, keeping it to himself and never suspecting that events would dictate that Tom would need to tell me so soon.

What had happened was that the reporter from the Sunday Mail had found my father. Once again the tabloid press had managed to cause havoc in our family. Earlier that day, Tom had been driving home when my father called him, fuming and ranting about a reporter outside his front door. It is difficult to express the intensity of my father’s rage. I am sure that even as a dying man it would be terrifying. Suddenly Tom saw a police car parked on the side of the road and so took the phone away from his ear for a moment. When he picked it up again our father was still railing, so Tom assured him he would deal with the matter and hung up. He panicked that our father’s suspicions were correct and that the imminent shoot of my Who Do You Think You Are? had indeed prompted the news of my true lineage to somehow be leaked, and the idea that I might find out the news by seeing it splashed across the front page of a newspaper horrified him. He decided he had to tell me that night and called Sue to find out what time I was arriving.

After he’d spoken to me, he finished his journey home and then called our father back to tell him he’d set the wheels in motion and was on his way to tell me everything before I found out via the press. Of course this is when our father told him that the reporter hadn’t mentioned anything about who my real father was, but had in fact merely wanted a comment about that Times article. Our father’s fury was actually directed at me for having mentioned he had cancer, not that this massive secret had been exposed. Tom was distraught. But now it was too late, and he had no choice but to follow through.

“What about Mum?” I asked. “Did you talk to her about it?”

“Not yet,” said Tom. “I wanted to let her know I was going to tell you but I didn’t get a chance.”

“Don’t!” I blurted. “Don’t talk to her until this is all sorted out in my head.”