Читать книгу A Life of Pride - Alan G Pride - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 12

The Joys of Motorbikes and Girls

ОглавлениеPart of the attraction of Adelaide was our discovery of GIRLS. I don’t recall any proper sex education back then, it was probably just advice to abstain. But once hormones hit, most of us would no more have ‘saved ourselves for marriage’ than do today’s teens.

I’d already been propositioned, by an attractive young married neighbour. I was about 15 and she was probably bored and lonely, but I was too embarrassed to go along with it. Came 16 or so, though, my friends and I started chasing girls our own age.

And they laid down the law; “If it’s not on, it’s not on!” Condoms were the only reliable contraceptive for us, but getting them could sometimes be embarrassing. One of my friends wanted some, so I went with him to the chemist. Broken Hill being a town where lots of people knew each other though, it wasn’t easy. The first chemist had a girl behind the counter whom we knew, so we awkwardly bought sweets and kept going. The next chemist said in an outraged voice: “This is a Catholic establishment! We don’t sell that sort of thing here!” Even more red-faced, we hurried out. I think we had luck at the next one, but not surprisingly we sometimes turned to 'Tiger', a friend who was cheeky enough to buy boxes of condoms and resell them individually, at a huge profit.

And then, where to keep them so that our parents wouldn’t find them? I remember one weekend when we were planning to race off to a dry, sandy creek- bed out of town with our girlfriends for an evening’s bliss (our families probably thought we were at the cinema). My friend’s girl had agreed that this would be THE TIME – but where could he store the vital rubber ‘till then? I suggested: “Put it in your bike headlamp!” So off we went, each couple taking a blanket to their private love-nests along the creek. But when we regrouped later, he and his girlfriend were in a terrible mood – he’d forgotten the vital screwdriver to re-open the headlamp!*

I soon had the luxury of two girlfriends in Adelaide, as well as one in Broken Hill. One of the Adelaide girls was a lovely nurse who only had the weekend off occasionally. We’d go on hill-climbs, or rides, visit motorcycle shops, or race our bikes (I still have the certificate for winning a motorbike race at Sellicks Beach in 1950, a ‘Three Mile Event at an Average Speed of 95 Miles per Hour’ on my 500cc Triumph.) This probably wasn’t great entertainment for the girls, but I was very self-centered.

Other weekends I’d spend in the town of Mildura, about 260 k’s south of home, with my Broken Hill girlfriend.

The road then was mostly dirt and potholes. I had my 1916 Harley Davidson, an old-style bike with no proper pillion. It only had a luggage carrier on the back, so I strapped one of my mother’s cushions onto it and off we went. We bumped through Sandpar sheep station about 60 k’s out of Broken Hill, and stopped at the shop there. A bit after this we started hitting an area full of sandhills, a very tough ride. I’d charge up the sandhills with my girl clinging on behind, we’d just reach the top, then I’d lose traction and skid down the other side. Eventually, the dunes got so tall that she would have to jump off and push while I revved the engine. Not very pleasant, because she’d be getting sprayed with a rooster-tail of sand from the wheel! As soon as I got traction I had to keep the bike under power to reach the dune crest, so I’d be sitting there with the engine idling, waiting for her to catch up. No way to impress a girl! She was doing the same sort of job I’d done on the trip to Quinyambie station, minus the shovel and roll of carpet. Why she kept going out with me, I don’t know.

The main attraction of Mildura, when we’d finally arrive, was the chance to be together away from the goldfish bowl environment of Broken Hill, staying at a nice boarding house run by the broad-minded Mrs Lamprey. She'd feed and house an obviously unmarried young couple without criticism. Once, we’d set off for home on a Sunday and ridden a long way, before realising that we’d left a condom under the bed! Crimson-faced, we raced back on the pretext of having forgotten something. She smiled at us and said, “Don’t you worry dears, I took care of it.”

*This bloke was quite a comedian. He had a fox-terrier which he'd taught to walk on its forelegs with its bum in the air, so that when people asked him why the dog walked like that, he could answer, “Isn't it obvious? It's so's I can use his arse for an egg-cup.”

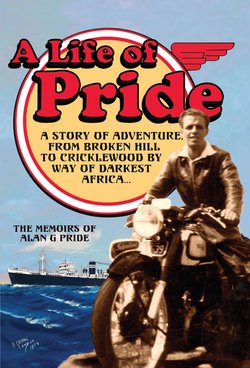

With one of my girlfriends. (The photo damage is explained in Chapter 24!)

1946 to 1951 were such a busy five years, I wonder how I crammed in so much. Working at the mine Monday to Friday, technical studies five nights a week and some Saturday mornings, buying and selling, riding, driving and socialising. In those years I owned at least 12 motorcycles and 3 cars. My first bike taught me not to buy any car or bike in pieces, because if it’s missing just one obscure piece, it would (long before the internet) take forever to find that piece. The 1934 BSA I kept for 5 months, making a profit on the £6 it cost me, by simply fixing its oil leaks. Then the 1916 Harley, followed by a 1929 Harley 750 with an overhead inset and 9 side valve exhaust – for 12 months.

At that time I was going to dances at the North Broken Hill community hall. I was chauffeuring my girlfriend of the time home, she wearing a long dress she was very proud of. Perched on the luggage-rack cushion, she gathered the skirt folds into her lap. Well, we hit a big bump and she lost hold of the skirt, the wind caught it and it blew straight into the chain, where it was doused in oil and shredded to bits! That was the end of our affair, I don’t think she even stopped to say good-bye. Oh well, so many girls, so little time!

My next bike was a £15 BSA Y13, a very rare bike today, and I know why. I reckon they all got junked, because this was a pig to ride. A 750 cc V-twin overhead valve, single carburettor and terrible oil leaks; it looked nice, long and low with a shiny green and chrome finish, but I only kept it a couple of months. I spent a bit of time polishing it up and sealing the leaks, doubling my money when I sold it.

After that came the all-time worst bike I’ve ever owned: a 1924 Royal Enfield with one of the last hand-change or one of the first foot-change gearboxes. I never went out on it without it breaking down. On one occasion, I was about 50 k’s north of Broken Hill on the Tibooburra road. I’d gone through Steven’s Creek and had a lime spider at the pub there, then onto the corrugated gravel road before Yanco Glen - when the Enfield stopped. I tried all the usual things to no avail; looked to the points, took out the spark plugs and so on. It wouldn’t start. So I just had to sit there by the empty road, wondering how long it would be before anyone came past. The silence out there in the desert is something you can’t appreciate, until you’ve been stranded in it. I thought of a young motorcyclist who'd disappeared after going out for a ride alone; months later, his shattered skeleton was discovered next to the wreck of his bike...

Eventually, though, a log truck came along and stopped. Since the greenbelt had been planted around Broken Hill, no one was allowed to cut down trees close to town, so woodcutters went further out. A full load of logs filled the back of the truck and I wondered if there was even room for my bike. The owner of the truck was a bloke called Kelly Staker and beside him was his young assistant, Laurie Heath, who would later become a good friend of mine.

So Kelly and Laurie climbed onto the top of this huge pile of wood and threw down a rope, so we could hoist the bike atop the logs.

We tied the bike down on its side, with petrol and oil leaking everywhere, and all three crammed into the cabin made for two. On the way back to Broken Hill, we talked about the wood-cutting business and for a while I toyed with the idea of getting a truck and going into the business. This would not have pleased my parents – they wanted a better career for me.

I think I sold the bike to Pro for £20, no more than I’d paid for it.

Next came an Ariel Square 4, a 1936 model with a 600 cc overhead cam and distinctive forward-pointing carburettor. It had nice silver panels and a chrome tank. Nowadays it's a rare and expensive bike: I paid £60 back then. It ran well and didn’t suffer from the Ariel’s common problem of overheating, because of their pre-war iron engine cylinders. I kept it for months, riding to Adelaide and back several times.

Once I went out alone on a weekend ride to Oodla Wirra, intending to stay overnight in the pub there and head back home on Sunday. I was a few k’s from Mingary, a tiny town with an old railway fettlers’ camp, a store and a service station. It was a very hot summer day, in the midst of a rabbit plague. The bunnies had bred up during wet weather, then as the scrub dried out they were on the move, looking for food. Suddenly the bike’s front tyre went flat. I put it up on the stand; tools out, tyre off – a torn tube! I had no spare and there was no other traffic on the road. So I stuffed the tyre tightly with dry grass, which would keep it in shape as I rode towards town. The grass soon crushed down to powder and the tyre started to smoke. Twice I had to stop, let it cool and restuff it, before finally getting into Mingary. The service station was just a tin shed with some 44-gallon drums of petrol outside, tarpaulins keeping the boiling sun off them. A big bloke in a blue dust-coat came out and asked, “Whadda you want?”

I explained about the wrecked front tube, now obviously leaking shredded grass. It just so happened he had a replacement, had had it around for years. He chucked it towards me, followed by a hand-pump to inflate it and didn’t offer to help as I wrestled it on. Only then did he tell me that he wanted £3 and I could take it off again if I didn’t like it. That was a huge rip-off, but I had no choice and he knew it. I paid – more than an apprentice’s weekly wage – and rode off fuming.

With all this delay, I was now heading into the evening and the rabbits were out in force. I couldn’t avoid them as they streamed across the road. So many went under the wheels that I almost fell off the bike: it was like sliding around on roller- skates! Then they started to jam up between the bike’s front forks and the wheel spokes, their heads banging against the bike as they raced everywhere. Dead ones were strewn all over the road from car and truck impacts and I couldn’t avoid adding to them. That’s what the rabbits were like then, before myxo and Kalesi virus were introduced to thin them out. I got to Oodla Wirra in one piece anyway, and spent the night there for less than that replacement tube had cost me.

Several months later, I decided to sell the Ariel. None of my friends were in the market for a bike just then, so I advertised it in the Barrier Daily Truth for £80 – 20 more than I’d paid, having done some work on it. A bloke called Jack Griffiths rang asking about it, and when he turned up, who should it be but the blue dust-coat who’d sold me that tube! He looked the bike over grimly for a while.

“You want it?” I asked at last.

“Yes, I’ll give you £80.” He started to count the money out of his wallet.

“No,” I said. “For you, that’s £83. Full stop.”

He glared at me. He hadn’t forgotten the tube rip-off either, so he knew full well what I meant, but it was pay up or go all the way back to Mingary without the bike. So he shoved £83 at me and I had my sweet revenge.

The next bike was a 1936 Panther, 600 cc with girder forks and overhead valve. The fault with this one was its coupled brakes (like Moto Guzzis’ have now), meaning one lever for front and back brakes – not a good idea.

I was coming back from a ride to Mt. Gipps, about 60 k’s north of Broken Hill, when I made the mistake of squeezing the brake lever hard on a gravelly bend. The brakes locked up and the bike jack-knifed, hurling me onto the road. I wasn’t badly hurt, but I got painful gravel-rash on the knees and decided to sell the Panther as quickly as possible.

I’d paid £90 for it, some of that borrowed from a bloke called Jack Wyatt, who worked with my father. Dad had long since guessed about the bikes and wasn’t happy. Somehow he found out about the loan too, and harassed poor Jack. So, longing for ever newer and better bikes – more than I could afford on my ‘prentice’s wage – I took out a loan from a finance company, persuading my hapless mother to act as guarantor.

This was a bad idea, but I was too young and self-centred to let it stop me. My mother had no income (Dad kept her short of even grocery money, as I’ve said,) but she doted on me and signed the papers without telling him. And the results were eventually worse for her than for me. The bike I craved this time was a BSA B33, my first new one and almost my last. I rode it for about a year, to Adelaide and Wilcannia, on Menindee Lakes camping trips, to the Mildura boarding-house, and to work.

One morning I was heading to the mine, running late and speeding to make up for it. So I raced up to the top of South Hill. There, at the T-intersection from the South Mine, was a lady in a brand new Hillman Minx, pulling out straight in front of me! The bike smashed right into the car’s side, I sailed over the top of it and in those days of no crash helmets, my scalp was ripped open. I was taken to the mine and laid on a bench to wait for an ambulance, blood everywhere. Quite a few stitches were needed – I have a scar to this day.

Well, of course the proverbial ‘hit the fan’ at home. The driver of the Minx was a lady called Mrs Lennox. The name sounded familiar and I realised that her husband owned the main bus company in town. He hired a solicitor to pursue the case and try to find out who was at fault. I knew I was, but luckily I’d left no skid marks on the road before the impact, so the police weren’t able to work out how fast I’d been going. But the BSA was a write-off, with its forks driven back right into the engine. I still had to keep paying it off and my father was furious.

“You’ll end up driving the SHIT-CART and nothing else, the way you’re going!” he roared at one point.

The worst thing was the trouble this caused between my parents. Dad hated debt and disobedience: Mum had gone guarantor for me behind his back, using ‘his’ money, as he saw it. He’d never been demonstrative or indulgent with her – when challenged as to why he never took her out or went on holidays, he replied: “You don’t chase a bus once you’ve caught it.” I think he was also jealous of the way she doted on me. (Having her mother living with them didn’t help either, as they had little privacy. At least Sophia provided company, Dad being the workaholic he was.) So they drifted apart. I planned to fly the coop as soon as my apprenticeship was finished, but Mum was stuck there.

The next bike I owned in Broken Hill was my favourite, an International Norton. I had so much fun and adventure on this bike! It was powerful and reliable, built, I reckon, from the plans of a road-racing bike, a smaller brother of the Manx Norton. That really is a racing bike; the difference being its full set of lights and lower compression engine.

I did thousands of miles on it over the next 18 months. Its first long trip was down to Victoria, including the Great Ocean Road, a demanding route that weaves back and forth along the coast. In places it’s cut into the cliffs far above the sea; and back in the 1940s, it was mostly dirt and gravel, with no fences or armco barriers between me and a long drop. I concentrated hard as the Norton slid on the gravel - it was like riding over marbles.

It was on this trip that I had another of my Lucky Escapes. I was en route from Adelaide to Melbourne via the Coorong, a vast length of straight, flat, dirt road beside the sea. My mind wandered in the late afternoon and my speed crept up. A big rear-engine bus was chugging along in front of me, throwing up blinding clouds of dust. Absent-mindedly I pulled out to pass it, needing a minute to draw level with the bus. Then through the dust I saw a huge truck, barrelling head-on towards me! I couldn’t drop back behind the bus in time to avoid crashing into the truck, or the trees on my right, so I leaned flat on the bike, squeezed every last bit of speed from it, and swerved in front of the bus just a second before the truck roared past.

I never forgot that moment of absolute terror, but it didn’t put me off riding, nor did the dust and discomfort of the trip. Indeed, I was so pleased with the bike’s performance that I could hardly wait to ride it all the way to Perth when the mine shut down for three weeks at Christmas. Several friends promised to ride with me, but it was going to be the height of summer and one by one they wimped out. Everyone assumed that I wouldn’t do such a long ride alone – thousands of k’s each way – but this just made me more determined.

In preparation, I bought a set of knobbly tyres which could better handle gravel and dirt, though they made the bike look clumsy. I made and fitted a frame over the back wheel to hold a gallon (4.6 litres) container for petrol on one side, a gallon of water and a pack of tools on the other. A haversack was fastened over the rear wheel. On my back I carried a rolled-up swag - a blanket and piece of canvas. Off I went.

It was a hard but very satisfying ride. From Broken Hill down the Barrier Highway to Peterborough, across to Port Augusta, then down the Lincoln Highway to Port Lincoln and up the Flinders Highway to Ceduna. Then the 1200 kilometre run along the Eyre Highway from Ceduna, across the Nullarbor Plain to Norseman, and finally a 700 k meander into Perth.

The roads were mostly dirt and sand, hot and deserted. The Nullarbor was the worst. It had originally been made with a grader, but the distances were so vast that no council could keep it in repair. So drivers would just make their own roads, by driving alongside the original once it had become impossibly potholed and corrugated. Along the way I’d pass abandoned cars, many in good condition apart from broken axles or crankshafts. Even though cars were much dearer then than they are now (compared to a weekly wage) it just wasn’t worth getting them towed out. I remember one Vanguard which, but for the dust, looked as though it had just come out of the showroom.

Mile after mile I rode, with the ocean of the Great Australian Bight on my left and the flat desert on my right. A breakdown or accident on that long empty road in summer could have been fatal, but of course I had a teen’s feeling of invulnerability. I fell off the bike many times, luckily without serious damage. At night I’d sleep on the ground, digging a hole for my hip and unrolling my swag, using my boots for a pillow.

I rode into Perth so covered in dust, I must have looked like a ghost. Digging into my filthy haversack, I found my camera and a startled young woman pushing a pram agreed to take a photo of me sitting there, in the centre of Perth (much more a country town than it is now) to prove I’d made it.

I spent a few days there before making the return trip, and by the time I set my feet back down in Broken Hill I’d had enough of dirt roads to last a lifetime. The Norton had performed brilliantly, though.