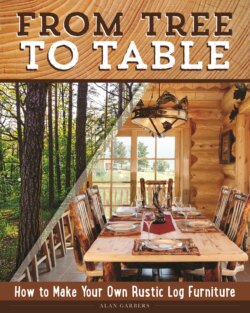

Читать книгу From Tree to Table - Alan Garbers - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Selecting Trees

ОглавлениеStarting out, select trees that are as straight as can be found. The straighter and more cylindrical a log is, the easier it is to work with. It will make designing and building furniture much easier. As you gain skill and experience, you can use less-perfect logs that will give your furniture wonderful character.

I often start off into the woods with a project in mind and I want to see if I can find the wood to support the idea. I usually carry bright surveyor’s ribbon to mark the trees I think I want. That makes it much easier to find the right trees when I return with a saw.

While selecting trees, we need to realize what size of logs we need for the project. Two-inch-diameter (50 mm) logs work great for bar stools. Four- to six-inch (100–150 mm) logs are about right for bedposts. Three-inch (75 mm) logs work well for crosspieces on a headboard. Small saplings of various sizes work well for braces and decorative members.

Bear in mind that humans like symmetrical things. We like to see things that match in color and size. A bar stool with varying sizes of legs is going to look awkward, and a set of them is going to be even worse. My point? Be sure to cut enough wood of matching size to do the project. In fact, cut extra wood. Why? Because it takes a long time for wood to dry, and running out of wood can delay a project for a year or more.

I made a mistake years ago. A lodge owner wanted me to make a set of bar stools, but he wanted to see one first before he committed to the deal. I went to work and made one heck of a bar stool, which included a forked hickory stick in the backrest. It was my way of showing off what I could do and a way to use up something I had been saving for that “special” project. Dang it if the lodge owner didn’t love the bar stool and wanted all of them to have forked sticks in the back! Do you know how hard it was to find three more forked hickory sticks of the same size for the backs? Do you know how hard it was to get the sticks dry and on the stools in the allotted time? I learned my lesson.

I can’t say this enough: Cut lots of extra wood. Some trees are very prone to rot that can’t be seen from outside; sassafras is notorious for this.

Avoid heavy branching. Trees that grow in the open are notorious for this. Each branch is a knot you have to deal with. If you insist upon using a tree with lots of branches, cut and peel it in the early summer so the bark will be easier to remove around the branches.

Another issue is bark or wood coloration. Again, sassafras can be a nightmare for color differences. Sassafras is a wood that looks best with the bark on but sanded to reveal the redwood-colored bark underneath the weathered bark. The color variation can be maddening, but somewhat predictable if attention is paid to how old the tree is. Young, fast-growing trees have a lighter, yellowish red bark without much in the way of vulgs. Older trees have a bold, beautiful red with moderate vulgs. Old trees have a deep, dark red with deep vulgs. In case you’re wondering, vulgs are the deep splits that are made in the bark as the tree grows.

The last thing you want to happen is to run out of wood. Your projects will suffer for it.