Читать книгу Walks in the Cathar Region - Alan Mattingly - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

This castle hath a pleasant seat; the air

Nimbly and sweetly recommends itself

Unto our gentle senses.

Macbeth, Act I

There is a point on a walk in this book where, after an hour or so’s steady walking uphill on a track which winds through fields and woods rich in wild flowers and fungi, you emerge into a large clearing on high ground.

Imagine that you are standing there now. To the north, the ground falls and rises in a series of valleys and ridges. It is a warm, sleepy, thickly wooded landscape, rural France at its most rural. These are the foothills of the eastern Pyrenees. They ripple northwestwards towards the cathedral city of Toulouse and northeastwards to the medieval spires of Carcassonne. At their far eastern end they meet the coastline of la grande bleue, the Mediterranean Sea.

In places, movements in the earth’s crust in recent geological times thrust skywards immense slices of these foothills. Later, powerful torrents, fed by melting ice during colder millennia, sculpted from these blocks steep-sided peaks and razor-edge ridges. Much later, human beings seeking protection from their neighbours, bandits and invaders built fortified settlements on many of the high, isolated locations which natural processes bequeathed to this region. Their owners constantly restored and strengthened those fortresses.

By the early medieval period this region was known as Languedoc. It was divided into a large number of near-independent baronies whose lords each possessed one or more castles. Many of those fortresses are today celebrated throughout the world as ‘Cathar castles’. From your imaginary position, you are about to understand why the castles have achieved such fame.

Over your right shoulder, the ground rises again, to a hill covered in beech forest. Your footpath curves in the direction of that hill, and as you turn to cast your eye along its route, you may see white mist rushing up the left-hand side of the hill from far below. If the mist then starts to clear, be prepared for your jaw to drop. For what will emerge from the cloud, just beyond the beech-covered hill, is the sight of one of the most awesome and evocative rock pinnacles in Europe. There, soaring into the sky like a gigantic upright megalith, its craggy limestone slopes gleaming white, looms the 1200m Pog de Montségur (pog comes from the Occitan language, and means hill or mountain – see Montségur, section 9). On the very summit of the pog sit the formidable remains of the most renowned fortress in Cathar castle country.

It was here in 1244, after a siege lasting several months, that the principal mountain stronghold of the ‘heretical’ Languedoc Cathars fell. It was taken by the far superior forces of the French Crown and the Catholic Church. Shortly afterwards, 200 Cathars were burnt alive at the foot of the mountain.

Who were the Cathars?

The term ‘Cathar’ was not used by the followers of this faith – who referred to themselves simply as Christians – but was employed by the Catholics when labelling this particular group of heretics. It may originally have been a term of offence, meaning cat-lover – that is, a sorcerer or witch. The Cathars’ ‘priests’ – women as well as men – were referred to by their Catholic opponents as ‘Perfects’, meaning perfect (that is, complete) heretics. But they were known by their followers as simply good Christians, or Bons Hommes and Bonnes Femmes.

Monument to the Cathars who were burnt at the stake below Montségur castle, 16 March 1244 (Section 9)

However, they had profound theological differences with the Catholic Church. In particular, they had a belief – dualism – that good and evil spring from different sources. Therefore the material world – which they saw as plainly evil – could not have been created by the God of the Bible. Such a belief was totally at odds with Catholic doctrine. The Cathars even saw the Catholic Church itself as the work of the devil. The broadcasting of such opinion was not a good strategy for surviving the heretic-burning years of medieval Europe.

The Cathar faith took root in Languedoc in the 11th century. The Bons Hommes and Bonnes Femmes who preached it were ascetic; they worked in the community as, for example, craftsmen; they preached in a language that everyone could understand; and they levied no taxes. Not surprisingly, their popularity spread rapidly among the independent-minded people of Languedoc. The region’s ‘nobility’ (its warlords) protected them; indeed, many members of ‘noble’ families in Languedoc were themselves Cathars.

From the outset, the Catholic Church saw the Cathars as a threat to its very existence. The French Crown, whose territory at that time was confined to the northern part of what is now France, became eager to take possession of Languedoc. These two irresistible forces, Church and Crown, together met head-on the immovable object of the Cathar faith. They launched against the Cathars a crusade just as cruel and bloody as those dispatched to ‘save’ the Holy Land. After a long struggle, the Cathar church was exterminated and the French Crown seized Languedoc.

After the crusade, the border of France moved south to Cathar country. It needed strong fortification against France’s Spanish neighbours, so the French rebuilt and strengthened several of the castles in which the Cathars had once taken refuge. In the 17th century the border moved south once again, after a war that ended in triumph for the French. That left many of the ‘Cathar castles’ a long way north of the new border. The castles thus lost their strategic importance; most were demolished or abandoned, and then fell into ruin.

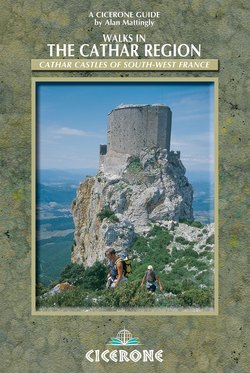

And thus the ‘castles in the sky’, now symbols of the Cathar faith and its demise, were bequeathed to posterity. The sometimes romantic, sometimes forbidding castles such as Montségur, Quéribus, Puilaurens, Peyrepertuse and Lastours became the centrepieces of fantastic fables and, in our time, tourist attractions of international repute.

The citadels we see today would have mostly been unrecognisable to the Cathars; in the majority of cases, the remains are of structures that were built after the Cathar period. But no matter: what is beyond dispute is that the castles offer stunning sights and are fascinating places to visit. They are irresistible focal points for fine walks in a lovely part of the French countryside. They will also forever be linked to the thought-provoking story of the Cathars, which touches everyone who visits this region.

Walking and thinking go together. Cathar castle country offers profound opportunities for both.

Languedoc, the ‘Cathar castles’ and the Pays Cathare

In medieval times, Languedoc was a large region in what is today south-central France. Its name was derived from the language spoken by its inhabitants (the langue d’oc – see below). The region was not a single administrative unit; its unity was based principally upon its language. The main city was Toulouse, in the west. Languedoc extended north towards the Dordogne, east towards the Rhône valley and south towards the Pyrenees.

Languedoc was invaded and occupied successively by the Romans, the Visigoths, the Moors and the Franks. In the 10th century it was divided up into feudal principalities, the biggest of which was the domain of the Count of Toulouse. Those principalities were not part of the French kingdom.

The Cathars propagated their beliefs in Languedoc from around the 11th century. In the middle of the 13th century, following the crusade that was launched to crush them, Languedoc became part of the French kingdom.

Today, the name ‘Languedoc’ survives in the title of the administrative region known as Languedoc- Roussillon, covering the administrative departments of Aude, Gard, Hérault, Lozère and the Pyrénées-Orientales. But medieval Languedoc was much bigger than today’s Languedoc-Roussillon region.

The langue d’oc was a collection of Roman dialectics spoken in much of what is now southern France. It is in contrast to the langue d’oïl, the collection of Roman dialects which was spoken in the northern half of France and which formed the basis of the French language. The term langue d’oc is synonymous with ‘Occitan’. It was a major language of culture in the Middle Ages and is still spoken today. Occitan is also used as an adjective, meaning of or from the area where the Occitan language is spoken.

The so-called Cathar castles are the medieval fortifications (or, more often, just the remains) that are found in Languedoc and located in places where the Cathars lived, preached or sought refuge. Many were built on vertiginous cliffs, crags or steep-sided pinnacles. They are striking in appearance and are loaded with sombre history and mystery. Today, these castles attract pilgrims, tourists, historians, archaeologists, writers, painters, treasure-hunters and charlatans with one of the most powerful magnetic forces of its kind in Europe.

Many of the castles were substantially reconstructed after the time of the Cathars. Little is known about how most of them looked when the Cathars inhabited them. However, they are located on sites with strong historical connections with the Cathars. ‘Cathar castles’ is a therefore a perfectly acceptable title.

A little information about each of the castles is given in the walk descriptions. The emphasis here is on walking rather than monuments, so this book does not offer detailed accounts of history, archaeology and legends. Plenty of literature covers those topics, much of it in English; books, leaflets and other publications are offered for sale at many of the castles, and in shops and information centres round about (see Appendix 2).

An entrance fee is charged for access to most of the Cathar castles featured in this book. Subsequent chapters give general indications of the times of the year when these are open to the public. Detailed information about current opening times can be obtained from local tourist information offices (see walk descriptions and Appendix 1). If you plan to visit several castles and other monuments in the area it is worth buying a carte inter-sites, which gives a discounted entrance fee to 16 places.

Bear in mind that some castles merit a long visit; you could spend half a day exploring the nooks and crannies of the extensive remains of Peyrepertuse. At the other end of the spectrum, there is very little left of the castles at Montaillou and Minerve. However, the latter are worth seeing, as they provide a tangible link to poignant historical events.

Looking down on Foix from a viewpoint on the Foix walks (Section 4)

Anyone who visits the area will see Pays Cathare (‘Cathar country’) signs along the way. The French department of Aude, centred on Carcassonne, refers to itself as the Pays Cathare. However, this name is used by public and commercial organisations over a much wider area than that covered by Aude alone.

The Sentier Cathare long-distance footpath runs east–west across Cathar castle country, from Port-la-Nouvelle on the coast to Foix. It is a popular route, and sections of it are incorporated in some of the walks in this book. The Aude department’s Pays Cathare logo appears on signposts along much of the Sentier Cathare.

That logo is used widely throughout Cathar castle country. It is a curious emblem which apparently depicts the sun (or maybe the moon) rising above the land. In doing so it represents the influence that the Cathar religion radiated over this country. The sun/moon is divided into a black sector and a white sector, representing the dualism of the Cathar faith. The slightly scribbled appearance of the motif is said to denote the ‘cuts’ that were inflicted on this region by the painful events of the crusade against the Cathars.

Subtle the Pays Cathare logo may be, but the extent to which the Cathar theme is exploited to attract tourists is the antithesis of subtlety. Signs and advertisements for enterprises with names like ‘Cathar-ama’, ‘le relais Cathare’, ‘Cathare Immobilier’ (an estate agent) proliferate. A 20th-century motorway (the A61 west of Narbonne) has been named ‘le chemin des Cathares’, and a sign at an exit from the A9 coastal motorway even offers you a welcome to ‘the beaches of the Pays Cathare’.

The Pays Cathare logo seen here on an information board near Quéribus castle

When you are in the country of the Cathars, you can count on being frequently reminded of your whereabouts.

‘CATHAR CASTLE COUNTRY’

This term has been coined simply for the purposes of this book, and the area so defined lies in a part of Languedoc that is southeast of Toulouse. Béziers is in the northeast corner; the Mediterranean forms its eastern border; the southern border is a line running roughly between Perpignan and Ax-les-Thermes; and the Ariège valley, which runs through Foix, forms the western border (see the Overview Maps). Most of the best-known Cathar castles are found within Cathar castle country.

However, it should be remembered that the Cathars were based over a much wider area than that defined as ‘Cathar castle country’. The Cathars’ main centre was Toulouse; their influence extended far to the north of Carcassonne, to Albi and beyond. The name often given to the crusade launched against the Cathars – the Albigensian crusade – is derived from the Cathars’ association with Albi. The Cathars were also numerous in other parts of western Europe, including northern Italy and the Rhineland; but in all these places they were sooner or later ruthlessly crushed by their enemies.

Getting there

It is possible to reach Cathar country by plane and/or train from many parts of Britain in a day.

By air

There are major international airports at Toulouse, Montpellier, Marseille and Barcelona with direct scheduled flights from a number of places in Britain (for example, at the time of writing Easyjet has flights from several British destinations to Barcelona, and from London to Toulouse and Marseille). From each of those airports there are rail connections and motorways giving relatively fast connections to, for example, Carcassonne, Béziers and Perpignan. Rail and road connections from Toulouse south to Foix are also good.

Ryanair has flights from London to Carcassonne, Montpellier, Nîmes (not far from Montpellier) and Perpignan; from Liverpool to Nimes; and from several British cities to Girona. (Girona airport is northeast of Barcelona, and gives easier access than Barcelona airport if you are then driving north to France). Flybe has flights from Birmingham, Southampton and Bristol to Toulouse and, in the summer, from Birmingham and Southampton to Perpignan.

By rail

If you travel all the way from Britain by train, via Eurostar’s Channel Tunnel service to, say, Béziers, try to change trains in Lille rather than Paris. That way you only have to cross to another platform, not to the other side of a city.

The ‘Cathar knights’ – huge modern sculptures by Jacques Tissinier – overlook the A61 motorway near Narbonne. The knights greet many visitors who travel from the north to Cathar castle country.

By road

You can get to Cathar castle country by coach, but London–Perpignan takes around 24hr. For information contact Eurolines (tel: 08705 143219; www.nationalexpress.com).

If you travel by road, you can cross France on autoroutes (motorways) all the way – bear in mind that these are toll roads. They can be extremely busy in school holiday periods, especially in July and August. There are often long hold-ups in high summer on the A7 autoroute between Lyon and Orange, which funnels holiday traffic down the Rhône valley.

General travel information

Information can be obtained from: French Travel Centre (see Appendix 1); French Railways (tel: 0870 8306030; www.raileurope.co.uk); British Airways (tel: 0870 850 9850 within UK; tel: 08 25 82 50 40 within France; www.britishairways.com) and Ryanair (tel: 0871 246 0000 within UK; tel: 08 92 55 56 66 within France; www.ryanair.com).

For SNCF, the national French railway service, contact www.sncf.com. It has an English version and gives times and prices of rail services in France.

The Thomas Cook European Timetable for trains across Europe is worth consulting if much of your travelling to and around Cathar castle country is by rail. A new edition is published every month, and it is widely available in British bookshops for around £10.

Getting around

Main roads and railway lines within Cathar castle country are shown on the location map (see the Overview Maps). There are two main east–west transport axes:

Narbonne–Carcassonne– Toulouse corridor, followed by the A61 autoroute and by good rail and bus services.

Perpignan–Quillan–Foix corridor, followed by a main road, the D117 (single carriageway for most of the way). Bus services run along this corridor, but they are infrequent (more frequent at the eastern end). A summer tourist train service, the Train du Pays Cathare et du Fenouillèdes, operates between Rivesaltes (north of Perpignan) and Axat (just south of Quillan) – see http://www.tpcf.fr.

There are three main north–south transport axes:

Béziers–Narbonne–Perpignan corridor, parallel and close to the Mediterranean coastline; followed by the A9 autoroute and good rail and bus services

Carcassonne–Quillan corridor, along the Aude valley. This is also followed by a main road, the D118 (single carriageway for much of the way). There are reasonably good rail and bus services between Carcassonne and Quillan

Toulouse–Foix–Ax-les-Thermes corridor, along the Ariège valley. The main road through this corridor is the N20 (partly double and partly single carriageway). There are good rail and bus services along the corridor.

The Bassin des Ladres in the centre of Ax-les-Thermes – a good base for exploring much of Cathar castle country. (The pool is fed by a hot spring and has been here since the time of the Cathars; sore feet love it.)

Elsewhere public transport services are scarce. Buses serve several towns and villages away from these main transport corridors, but these are often mainly designed to get children to and from school. They are therefore infrequent and may not run during the school holidays.

Other roads, of intermediate and minor status, wind across the hills and valleys and carry relatively little traffic. They can be pleasant to drive or cycle along if you are not in a hurry, but you do have to be constantly on the alert for fast-moving vehicles that may suddenly come hurtling towards you around the bend just ahead.

Accommodation

Places to stay are plentiful, from simple campsites to swanky hotels. Some advice is given later in this section about how to locate and reserve the sort of accommodation that you want. If in doubt, good starting points for making enquiries and seeking relevant literature are the French Travel Centre in London or a relevant tourist information office in Cathar castle country (see Appendix 1). Many bookshops in Britain also sell guides to accommodation in France.

Most hotels, gîtes, campsites, and so on are open from Easter to October. Many, especially those in or near cities and large towns, are open for all or most of the year. It is highly desirable to check room/bed availability in advance and to reserve accommodation. This is especially so for July and August, when many establishments are fully booked, and for those places near the coast or in internationally renowned tourist sites like Carcassonne. In addition, several establishments in the countryside are closed for all or most of the winter months.

Many establishments, in all price ranges, have not only e-mail addresses, but also websites giving information about their facilities and inviting you to book accommodation online. It will soon be the norm for accommodation providers to offer an online booking facility.

Gîtes d’étape are rather like youth hostels. They are reasonably priced and most towns and sizeable villages have at least one. Many are run as private enterprises, but often they are managed by the local commune. Like youth hostels, they vary a good deal in size, comfort and facilities. You can’t always count on getting meals, but there is usually a café, restaurant or grocer’s nearby. See www.gite-etape.com. The website www.gites-refuges.com is another useful source of information about gîtes and other types of simple accommodation.

There are four youth hostels in the area: Carcassonne, Bugarach, Quillan and Perpignan. The French Youth Hostels association is at 9 rue de Brantome, 75003 Paris; tel: (00 33) (0)1 48 04 70 30; www.fuaj.org.

Gîtes rurals are self-catering houses, cottages or apartments in the countryside or along the coast. These too vary considerably in size and facilities, but quality is generally good and they can offer excellent value for families or small groups who want to establish a base for a week or two and go out on day excursions. You can get particularly good bargains if you book out of the main holiday periods. Contact Gîtes de France: La Maison des Gîtes de France et du Tourisme Vert, 59 rue Saint-Lazare, 75439 Paris Cedex 09; tel: (00 33) (0)1 49 70 75 75; www.gites-de-france.fr.

There are plentiful chambres d’hôtes, the French equivalent of bed and breakfast establishments (indeed, an increasing number are advertising themselves as ‘bed and breakfast’). Gîtes de France also promotes chambres d’hôtes and is a good source of information. Bed & Breakfast in France 2004 (£12.99) is a co-publication by the AA and the French Gîtes de France which lists over 3000 bed and breakfast establishments around France.

Hotels are not quite so abundant, but you won’t have any trouble finding one if you stay in towns like Carcassonne and Quillan, or head for large villages like Montségur and Cucugnan which are close to the best-known Cathar castles. Hotels which bear the Logis de France label seem to be invariably reliable and good value. The Logis de France guidebook to its recommended hotels is sold in some bookshops in Britain and France and is worth buying; for central reservations tel: (00 33) (0)1 45 84 83 84; see also www.logishotels.com. The famous Michelin red guide to hotels in France can also be invaluable. Lists of hotels in and near particular towns can be looked up on www.viamichelin.com.

Auberge is a term adopted by a wide variety of establishments. Some are gîtes d’étape, others are hotels. What they generally have in common is that there is a restaurant of some sort on the premises.

Campsites abound; for information see www.campingfrance.com.

Stocking up

There are many towns and large villages along the main transport corridors where you can count on finding at least one store, like a supermarket or épicerie (grocer’s-cum- general store), open on most days throughout the year. Bear in mind that, like almost everything else in France (apart from restaurants), they will probably be closed for two or three hours from midday. Most such places also have a chemist (pharmacie – look out for a flashing green cross), a boulangerie (bakery) and other shops.

Banks and post offices are more widely spaced out. The opening hours of many banks may be restricted (for example, mornings only). If you can’t find a post office and you only want a few stamps, try a tobacconist – they usually sell them.

Stock up when you can. Several farms along the way sell excellent produce, as here on the Pech de Bugarach walk (Section 16).

Distances between petrol stations can be quite considerable, even along the main transport corridors. When they are not staffed, some operate automatically with credit card machines – but the machines may accept only French credit cards. Remember too that some of the simpler accommodation establishments will not accept payment by credit card. That can also be the case in many small shops, bars and restaurants that will only accept payment by French cheque or cash.

Away from the main transport corridors, many villages are now without permanent shops, bakery and even bars. Some have such facilities, but they are only open in the peak holiday periods. Local residents may rely upon ‘travelling shops’ – vans and lorries loaded with food and everyday items, which tour villages, acting as a mobile épiceries.

Along long-distance paths and other well-used walking routes, farms will often sell cheese, milk, honey, fruit and so on to passers-by.

It’s a good idea to keep well stocked-up with essential foodstuffs (if you are on a cross-country trek), with petrol (if you are motoring), and with cash – however you choose to travel.

Maps

The sketch maps accompanying the walk descriptions in this book are intended only to offer an indication of the key features in the areas crossed. It is strongly recommended that walkers also equip themselves with the relevant 1:25,000 maps published by the Institut Géographique National (IGN), the French equivalent of the Ordnance Survey in Britain. These excellent maps contain very detailed topographical information. Each walk description specifies the 1:25,000 map (or maps) which cover the relevant area.

There are two types of 1:25,000 map. Maps in the Serie Bleue series each cover an area of about 15km x 20km. Maps in the Cartes topographiques TOP 25 series vary in size but typically cover an area of about 27km x 22km.

Always keep a map in your pack (seen here below Puilaurens castle, Section 11)

The TOP 25 maps show long-distance paths, local walking routes and a lot of other valuable tourist information, much of which is not shown on the Serie Bleue maps. They cover coastal, mountain and other tourist areas. In Cathar castle country, most of the 1:25,000 maps are in the TOP 25 series.

A grid of numbered kilometre squares covers the maps of newer editions of both 1:25,000 series. The newer editions can also be used with global positioning devices (a GPS symbol is shown on the front). At the time of writing, about two-thirds of the 1:25,000 maps referred to in this book are GPS-compatible. The newer editions of all 1:25,000 maps are also being marketed as Cartes de randonnée (walkers’ maps).

Many newsagents, bookshops and supermarkets in France sell IGN maps. TOP 25 maps cost around 10 Euros each (about £7), while a Serie Bleue map costs around 8 Euros.

The publisher Rando éditions has produced a series of 1:50,000 maps covering the French Pyrenees and their northern foothills, using IGN cartography and also called Cartes de randonnées. In this series, no 9, Montségur, covers an area between Quillan and Foix and is useful for planning walks in the area. It costs around 10 Euros.

The IGN also produces a series of 1:50,000 maps, but these are not usually available in shops and, for walkers, are no adequate substitute for 1:25,000 maps.

For route-planning purposes the IGN’s series of 1:100,000 maps (the Cartes topographiques Top 100 series, or Cartes de promenade) is very helpful. Nos 71 (St-Gaudens Andorre) and 72 (Béziers Perpignan) cover most of Cathar castle country.

IGN’s 1:250,000 maps (Cartes régionales series) are also designed for route planning by road. Cathar castle country is covered by Midi-Pyrénées (R16) and Languedoc- Roussillon (R17). In France, the 1:100,000 and 1:250,000 maps currently cost around 5 Euros each.

IGN’s website is www.ign.fr (in French only). Their maps and other products can be bought via that website using a British credit card. But, with the additional postage and cost of currency transfer, their final prices seem to work out a little higher than those charged by British suppliers of the same maps.

BRITISH MAP SUPPLIERS

Stanfords, 12–14 Long Acre, Covent Garden, London WC2E 9LP; te1: 020 7836 1321; sales@stanfords.co.uk; www.stanfords.co.uk.

The Map Shop, 15 High Street, Upton-upon-Severn, Worcs WR8 OHJ; te1: 01684 593146. (Freephone: 0800 085 4080); themapshop@btinternet.com; www.themapshop.co.uk.

Weather, equipment, risks

On the whole, the weather in Cathar castle country is very agreeable. Nevertheless – although the Mediterranean is not far away – don’t imagine that this region is similar to torrid Andalusia or bone-dry Crete. Rather, the weather is like that of Kent – only more so. Winter days are often cold and blustery, but springtime starts earlier and the summers are hotter and last longer. There are more sunny days throughout the year.

However, the climate has a great capacity to catch you out. A hot day in summer can start sunny and clear but a tremendous thunderstorm can suddenly build up in the early afternoon. Typically, that storm could – but not always – vent its fury in less than 30min. In winter there might be weeks of mild, dry weather followed by a day in which half a metre of snow is suddenly dumped on higher ground.

The occasional fierce and unrelenting winds may also surprise. One such wind is the tramontane, which comes from the northwest. Its often-cold temperature can be guarded against with adequate warm clothing and, insofar as it may blow away the clouds and let the sun shine through, it can be welcome. But take great care if you are walking on a hill or mountain ridge when the tramontane is at full blast.

WIND TURBINES

You will often see lines of wind turbines stretched out across high plateaux, now almost as characteristic of Cathar castle country as the castles themselves. None of the walks in this book passes beneath or very close to these.

Weather: usually sunny and warm, but be ready for occasional surprises (this was the summit of the Pech de Bugarach on an abnormal day in mid-April)

The climate also varies a great deal from east to west. On any given day, the weather in the east may be hot and dry, while in the west conditions could be cooler with occasional showers. The vegetation shows corresponding differences. For example, in the east you will find dry, open plateaux covered in garrigue vegetation – scented, often spiky Mediterranean shrubs and herbs. By contrast, in the west there is much humid deciduous forest, where beech trees grow to regal proportions.

Less surprisingly, the climate also changes with altitude. The walks in this book vary from a canal towpath walk at near sea level to a rugged mountain hike at an altitude of over 2300m. For the former, light clothing and trainers will be perfectly adequate, even on some winter days. For the latter you should wear walking boots and carry adequate warm and waterproof clothing at all times of the year.

It is difficult to generalise about the sort of clothing and equipment that you should take with you on these walks. If, for example, you are planning to walk between Easter and early autumn, and undertaking a wide range of walks (including the mountain routes), bring the same range of clothing and equipment that you would pack for, say, a summer walking tour of any upland range in England. Make sure that includes light clothing (T-shirts and shorts) because – if you are lucky with the weather – you may find that you wear little else.

If you already have some experience of walking in various types of terrain in Britain, you won’t need to be told that you should always carry a good map and a compass, especially if going into the hills. Make sure you are equipped with the relevant map(s) and carry a compass – and are capable of using it – when attempting any of the walks described in this book. If you have not done much upland walking before coming to Cathar castle country, read up about it beforehand – get hold of a copy of Cicerone’s The Hillwalker’s Manual by Bill Birkett.

Two things, however, do need to be stressed.

On a day’s walk in this region, at any time of the year, you will almost certainly build up much more of a thirst than you would when walking in Britain. Drinking water is sometimes available at natural springs or drinking taps. But it is best to assume that you will not come across any, so always carry plenty of drinking water with you.

Carry (and apply liberally!) effective sun lotion. In that respect this region does bear comparison with Andalusia and Crete.

A few other warnings are called for (see below), but don’t let these deter you from visiting Cathar castle country. It is, on the whole, a pretty safe place.

The sudden storms mentioned above can cause rivers to rise with amazing rapidity; dry streambeds can become raging torrents with a matter of hours. If your walk includes a stretch of dry riverbed, or a key river crossing, be aware that those sections may become impassable after very heavy rainfall. In the walk descriptions advice is given about possible options.

The storms may be accompanied by lightning. If you can shelter in a mountain refuge (or an orri, an old drystone shepherd’s hut) while a storm rages, well and good. But the likelihood is that the storm will break before you can reach one. Sit on your rucksack in open ground after laying aside anything metal (such as walking poles). You will get very wet, but you will minimise the risk of being struck by lightning. You should dry out quickly in the sun once the storm has passed.

Lightning may also cause fire. Fortunately, this part of France suffers much less from fires in forest and undergrowth than does hotter, drier Provence, further east. If you find yourself anywhere near an uncontrolled fire, get away from it as quickly as possible. Flames can move across the ground with startling speed, especially when fanned by a strong wind. Needless to say, walkers should take great care not to start a fire themselves.

If you are walking anywhere in this region from September to February, don’t be surprised to hear the occasional sharp crack of gunfire, probably from hunters tracking down wild boar or, on the higher ground, deer. You may also see signs alongside footpaths warning you that shooting is taking place in the area. It is very unlikely that you will be shot; the hunters have to comply with strict safety regulations, including not firing across footpaths. Stick carefully to the waymarked path and offer a cheerful bonjour as you go past.

You have even less cause for concern if you ever actually see a wild boar. The sight of anything resembling Homo sapiens will cause it to turn on its heels and dash off without a second’s hesitation. Wolves and bears live in Cathar castle country, but in extremely small numbers. They do eat sheep and other livestock for breakfast (in 2004 a bear polished off a couple of pigs in Niort, just south of Quillan, before being chased away), but your chances of meeting one of these creatures is infinitely small.

Pyrenean sheep dogs – big, beautiful, white-haired creatures – are often employed by farmers to guard flocks of sheep and goats while they graze. These dogs are usually unaccompanied by shepherds. They may utter a few warning barks in your direction, but present no danger to walkers. If you have a dog with you, keep it well under control (as in all circumstances). Pyrenean sheep dogs are trained to issue summary justice to bears, wolves and stray dogs which threaten their flock, so don’t give them reason to take issue with your pet.

Sheep and cattle are often fenced in. Even high up on open country you will come across wire fences. They rarely present an insuperable barrier, but always be careful how you cross them; they might be electrified. Some electric fences are powered by solar panels.

As caterpillars descend, plants shoot up. In spring and early summer undergrowth can rapidly become exceptionally dense, especially in the western part of the area. The paths followed on the walks described all seem popular, so the passage of walkers should keep most of them clear. But one or two sections were overgrown when the walks were surveyed. Where this may be a problem a suggested alternative route is given.

Finally, take a note of emergency telephone numbers, posted up in information offices, gîtes, hotels, and so on. If you ever need to telephone for help or to report an accident or a fire and are not sure who best to call, ring 18 (the French fire service, the sapeurs pompiers, which deals with many types of emergency). However, bear in mind that mobile telephones will not always work in remoter areas of countryside. Always ensure that you have adequate insurance in case you have to be rescued or need emergency medical treatment.

LOOK OUT FOR…

Snakes are rarely sighted, and the majority are not poisonous. Perhaps the most ‘dangerous’ creature that you are likely to encounter is – surprisingly – a caterpillar. In the early spring, especially beneath or near pine trees, you may see curious, worm-like lines of hairy brown caterpillars winding across the ground. These are processional caterpillars, that overwinter in a cotton-wool cocoon high up in a pine tree. They chomp on the pine leaves and can leave whole forests devastated. In spring they come down to earth, form head-to-tail chains and wander around looking for somewhere to bury themselves. Don’t touch them or get too close – they have a nasty sting. Above all, keep your dog well away, or you could be facing a distressing trip to the nearest vet.

Processional caterpillars: possibly the region’s most dangerous creatures

Waymarked walking routes

In Cathar castle country, where green tourism is flourishing, most communes (roughly equivalent to parish councils) have one or more waymarked walks in their territory. Often a notice board in the square of the main village will display these, and publications describing them may be available from the local tourist office or town hall (mairie).

It is becoming common practice for adjacent communes to band together as communautés de communes. Those joint organisations often take responsibility for planning, waymarking and publicising local walking circuits in the area they cover. An example in Cathar castle country is the Communauté de Communes Pays d’Olmes, based in the town of Lavelanet, east of Foix. It has developed a fine network of local waymarked circuits. Sections of those circuits have been incorporated in walks described in the Roquefixade and Montségur sections of this book. Later sections and Appendix 2 contain information about relevant publications covering local walks.

The Fédération Française de la Randonnée Pédestre (FFRP) has also published several Topo-guides for local walks (www.ffrandonnee.fr). These are for PR paths, Promenades Randonnées, which roughly means walks that can be completed in a day or less. Like the FFRP’s series of Topo-guides for GR (Grande Randonnée) long-distance paths, the PR Topo-guides have a uniform format. The maps, illustrations, route descriptions and complementary information are of a high quality.

Local walking circuits are usually waymarked in yellow – as on this signpost above Montségur (Section 9)

Relevant PR Topo-guides are referred to in Appendix 2 and in various walk descriptions. The local walks described in these guidebooks are waymarked with painted yellow rectangles. Most other local walking circuits in Cathar castle country are also now indicated by yellow waymarks (but not always: for instance, a section of the hill walk described in the Montaillou section is indicated by red waymarks).

GR paths carry red and white waymarks. A few – the GR7, GR36 and GR77 – cross Cathar castle country. Regional GRP (Grande Randonnée de Pays) paths carry red and yellow waymarks. There are a few of those in the area too, such as the Tours du Pays d’Olmes, near Roquefixade. The Sentier Cathare carries red and yellow waymarks for much of its route in Ariège, but blue and yellow waymarks in Aude.

It should be noted that where a section of a local walking route (normally indicated by yellow waymarks) coincides with the route of a GR or GRP path, the waymarks of the latter may take priority. The GR/GRP waymarks may thus be the only waymarks along that section of the local circuit.

For each walk there are notes on what kinds of waymarks to look out for, and (where appropriate) on which ones to ignore. For example, you may see waymarks consisting of a triangle and two adjacent discs, indicating the routes of mountain bike circuits. For the most part, they are best ignored.

Local walking circuits are susceptible to modification at any time. Please bear in mind that the routes of some of the walks described may be amended in the future. If in doubt, follow the routes indicated by any new waymarking on the ground.

The walks described in this book

The 16 walk sections describe several walks in Cathar castle country. All the walks follow waymarked and well-maintained routes. They can all be accomplished in a day or less. Several of the walks are circular; some are out-and-back walks, which return to the starting point by the outward route. A couple follow figure-of-eight circuits; one is a linear walk.

Each of the walk sections describes one or two walks. In a few cases, a variant of a walk is also suggested, giving the option of lengthening or shortening that particular walk.

Walks from other books and guides have not been simply copied (although the author is grateful to the French authors of other publications for the ideas and inspiration that they provided). Sometimes a section of one local walking circuit has, for example, been joined with a section of another. Elsewhere, a section of a long-distance path has been combined with part of a local circuit. All the walks have been selected for their quality and interest, for the absence of significant problems in following them on the ground, and have been carefully checked.

The waymarking varies from walk to walk. On the whole, the waymarking symbols used on the ground are self-explanatory. Simple rectangles or discs indicate that you should carry straight on. Symbols that bend or point to the right or left indicate that you are approaching a path turning. A cross usually indicates a route that you should not take.

The routes avoid road walking as much as possible. Where this is unavoidable, the roads concerned usually carry little motor traffic. But don’t be lulled into a false sense of security by the apparent tranquillity of the route. Listen and look out for approaching vehicles.

Each of the walk sections has a focal point. Most are Cathar castles, including the most renowned, such as Peyrepertuse and Quéribus. The walk (or walks) pass by, or are in sight of, the castle. In most cases there will be enough time to complete a walk and visit the castle on the same day. In a few cases it would be tiring and possibly impracticable to do, in which case you must save your castle visit for another day.

The order in which the walk sections are presented broadly follows an anticlockwise circuit around Cathar castle country (see the information box below), beginning in Béziers (where the crusade against the Cathars began) and ending on the summit of the Pech de Bugarach. It is hoped that this sequence will assist anyone who is touring the area. It also follows chronologically the story of how Catharism in Languedoc was crushed in the 13th and early 14th centuries. Each walk section contains a short commentary on the historical associations of the area with the Cathars.

How to use this guide

At the start of each walk section there is a summary of the following walk (or walks) and the area’s terrain. Next comes a look at relevant events in the Cathar story (‘Cathar history’) that relate to the focal point of the section – a Cathar castle or other location.

Foix castle: a famous emblem of Cathar castle country, and the finishing point of the walks in Section 4

You will then find practical information relating to the walk(s), including:

How to get to the starting point(s)

Points concerning navigation (with particular reference to waymarking).

A detailed route description of each walk then follows, starting with:

Estimated distance, altitude, walking time and relevant maps (including any variant).

Following the route description are:

A summary of any variant

A box containing points of interest along or near the route, and advice on how much time to allow for visiting the castle and/or other nearby places of interest and where you can obtain further information.

Please note the following:

Estimated visiting times, distances and altitudes are approximate (apart from a few specific spot heights).

‘Time’ is the estimated time spent while actually walking, including short breaks (for example, to take photographs and recover breath). It doesn’t cover longer periods for lunch, an afternoon siesta, and so on. Figures are based on the pace of a moderately fit and experienced walker who is alone or in a small party.

The description of the route contains bracketed numbers that correspond to numbered locations on the relevant sketch map.

For the most part, the description concentrates on route directions. Points of interest are highlighted in bold, and covered in more detail at the end of each walk description.

Sketch maps of the routes accompany the text.

Where two walks are described, there are sometimes two separate sketch maps; in other cases, both walks are marked on the same sketch map (in different colours).

Where a variant is described, only those sections that differ from the route of the main walk are shown on the sketch map.

Bonne promenade!