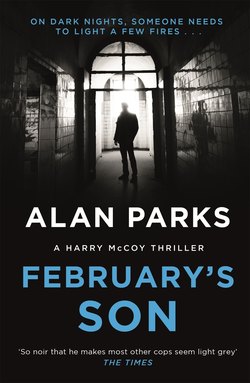

Читать книгу February's Son - Alan Parks - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

McCoy stopped for a minute, had to. He put his hands on his knees, bent over, tried to catch his breath. Could feel the sweat running down his back, shirt sticking to him under his jumper and coat. He looked up at the uniform. Another one of Murray’s rugby boys. Size of a house and no doubt thick as shit. Same as all the rest.

‘What floor is this now?’ he asked.

The big bastard wasn’t even breathing heavily, just standing there looking at him, raindrops shining on his woollen uniform.

‘Tenth, sir. Four more to go.’

‘Christ. You’re joking, aren’t you? I’m half dead already.’

They were making their way up a temporary stairway. Just rope handrails strung between scaffolding poles, stairway itself a series of rough concrete slabs leading up and up to the top of the half-built office block.

‘Ready, sir?’

McCoy nodded reluctantly and they started off again. Maybe he’d be doing better if he hadn’t just finished two cans of Pale Ale and half a joint when the big bastard had come to get him. Him and Susan were laughing, dancing about like loonies, Rolling Stones on the radio, when the knock on the door came. Big shadow of the uniform behind the frosted glass. Panic stations. Susan trying to open the windows and fan the dope smell away with a dishtowel while he kept the uniform talking at the door for as long as he could. Just as well they’d decided against splitting the tab he’d found in his wallet.

They climbed a few more storeys, turned a corner, and at last McCoy could see the night sky above them. It was grey and heavy, moon appearing every so often through the clouds and the falling rain. He stood for a minute, taking in the view, getting his breath back. Glasgow was laid out beneath him, dirty black buildings, wet streets. He walked to the side and looked out, didn’t want to get too close, no walls up here, just more rope handrails. Worked out he must be facing west, the dome of the Mitchell Library was right in front of him, university tower behind it in the distance. Below them the new motorway they were building cut through what was left of Charing Cross, a wide river of brown mud and concrete pilings. He heard footsteps behind him and turned.

Chief Inspector Murray held out his hand. ‘Sorry it’s a day early but Thomson’s away until Monday. Need someone working this soon as.’

For some reason Murray was wearing a dinner suit under his usual sheepskin car coat. Full shebang: dickie bow, cummerbund, silk stripe on the trousers. Only thing spoiling the dapper effect was the pair of black wellies he’d tucked the trousers into.

‘Lord Provost’s Dinner,’ Murray said, noticing him looking. ‘North British Hotel. Food was bloody swill. Never been happier to be called away to a murder in my life.’

‘Still trying to get you to take that Central job?’ asked McCoy.

‘Still trying, still not getting anywhere. No matter how many fancy dinners they invite me to.’ He took the unlit pipe out his mouth, pointed into the darkness. ‘Follow me, good pilgrim, for I am not lost.’

A path of damp stamped-down cardboard boxes led towards the far corner of the roof. There must have been ten or so people up here already, uniforms milling about, two technicians carrying the tent, even Wee Andy the photographer, almost lost in his duffle coat and a big woolly scarf. He could hear distant sirens; saw two ambulances crossing the river over to their side, blue lights spinning. Meant it wouldn’t be long until the press boys were here. Was hard enough to keep a murder quiet, never mind this one. A body found at the top of an unfinished office tower only a couple of minutes’ walk from the Record office? No chance.

‘Quite a view from up here,’ said Murray pointing. ‘Can see the cathedral. If it wasn’t pissing with rain you’d even be able to see the People’s Palace.’

‘Great,’ said McCoy. ‘Well worth climbing up fourteen bloody storeys for.’

Murray shook his head. ‘And here was me thinking leave might have changed you, but no, still the usual moaning-faced bastard that you are. How’d it go anyway? You go and see him?’

He had. Three two-hour sessions in a draughty back room in Pitt Street. Question after question.

How did you feel when you pushed him off the roof?

How did you feel when you saw the dead body?

How did you feel, really feel, inside at that point? Did you feel guilty?

What he’d really felt was an overwhelming desire to lean over the desk and punch the bastard in the face but he knew if he did he’d never get signed off so he sat there saying as little as possible, watching the clock. It was only when he got home he’d started thinking about the last thing the bloke had said to him.

Do you still feel happy being a policeman? Is it what you really want?

McCoy nodded. ‘Statutory three appointments all attended. Signed off. Psychologically fit for duty.’

Murray grunted. ‘How much did you have to bribe him?’ ‘So what have I missed?’ McCoy asked. ‘What’s the big news from—’

‘There’s the boy!’

They turned and Wattie was walking towards them, anorak, bobble hat and a pair of Arran wool mittens. He looked more like an enthusiastic toddler than a trainee detective.

He took a mitten off and pumped McCoy’s hand up and down. ‘Thought you weren’t due back until tomorrow?’

‘I’m not. Couldn’t keep away. Well, not when there’s some big bastard at your door telling you Murray needs you now.’

Wattie grinned. ‘Did you miss me? Because fuck me, I didn’t miss—’

‘Watson!’ Murray had had enough. ‘Get this crime scene secured now! Stop acting like a bloody schoolboy!’

Wattie saluted and walked back through the rain towards the lights being set up on the far corner of the roof.

‘How’s he getting on?’ asked McCoy, trying to fasten the top button of his coat, not easy with numb fingers.

Murray shook his head. ‘Bright enough, but he treats everything like a bloody game. Need you to knock some sense into him.’

‘What’s the story then?’ McCoy asked, looking round. ‘How come we’re freezing our balls off on the top of this building?’

‘You’ll see soon enough. C’mon,’ said Murray.

McCoy followed him along the cardboard path leading towards the other side of the roof. Three steps behind Murray again, just like always. Was like he’d never been away. Cardboard beneath his feet already starting to dissolve with the rain and the amount of people walking on it. Two uniforms were huddled over in the corner, big umbrellas being held over them not doing much to keep the water off. Both of them were fiddling with the battery packs, trying to connect them.

‘Fucking bastarding thing,’ said one, then noticed Murray. ‘Sorry, sir, just give us a minute.’ He grunted and finally managed to push a plug into the socket in the side. ‘Should be all right now,’ he said, putting his fingers into his mouth, trying to suck some feeling back into them.

‘Well then,’ said Murray. ‘What are you waiting for?’

The uniform nodded and clicked the switches down. Bright white light bounced back up off the wet roof. McCoy held his arm over his face, peered out through half-closed eyes. He’d never been good with the sight of blood, any blood, never mind this much. He took an involuntary step back. Edge of his vision was starting to blur, he felt dizzy. He shut his eyes, took deep breaths, tried to count to ten. He opened them again, saw the red everywhere, and turned his head away as fast as he could.

‘Christ! You could have warned me, Murray.’

‘Could have but I didn’t,’ said Murray. ‘Need to get over it. Told you a million bloody times.’ He looked over at the illuminated corner of the roof and grimaced. ‘Mind you, this is bloody hellish.’

It was. The blood was everywhere. Splattered up the half-finished walls, dripping from a flapping tarpaulin. Some of it had started to freeze already, red ice crystals glinting in the light from the big lamps. But most of it was still sticky and wet, giving off the familiar smell of copper pennies and butcher shops.

McCoy pulled his scarf across his mouth, told himself he was going to be okay and tried to concentrate. There wasn’t any way round it. To get any closer to the body he was going to have to step into the big puddle of blood. There was more cardboard laid down in it but it had half soaked up the blood, wasn’t going to make much of a difference. He put his foot down gingerly, felt the congealing blood tacky against the sole of his shoe. A tarpaulin snapped in the wind and he jumped, heartbeat going back to normal as he watched it break free and float off over the side of the building into the darkness.

He took a few deep breaths and stepped in, folded the edges of his coat over his knees and squatted. Tried to block out the cold and the rain, the sheer amount of blood, and tried to think about what he was looking at. It was a young man, late teens, early twenties. He’d been sat up against a pile of metal scaffolding poles, legs pointing out in front of him, arms hanging down by his sides. His left leg ending in a mess of tangled blood and bone, foot just attached.

Whatever he had been wearing had gone. All he was left with was a pair of underpants, pale skin of his legs and torso bluish in the bright lights. The words ‘BYE BYE’ had been cut into his chest, blood running down his torso.

McCoy counted down another ten like the doctor had told him and looked up into the man’s face. Despite everything, his hair was still combed into a neat side shed, raindrops on it glistening in the big lights. Below it, one of his eyes was completely gone, socket empty, some sort of vein emerging out of it, dried blood sticking it onto his cheek. His jaw was hanging slack, broken it looked like. There was something stuffed into his mouth. McCoy knew what it was going to be before he looked. He looked. Wasn’t wrong.

He stood up, ran for the side, feet sliding as he went, just made it to the edge before he was sick. When he’d finished he spat a few times, trying to clear his mouth of the taste of stomach acid and flat lager, watched it spiral down.

A tap on his shoulder and Murray handed him a hip flask. He took a deep pull, swirled the burning whisky round his mouth and swallowed it. Murray was shaking his head at him, looking at him like he was a uniform on his first day. He handed the flask back and Murray looked at him disapprovingly.

‘Give us a break, Murray. That your idea of fun, eh? Switch the big fucking lights on when I turn up? Christ, they’ve even stuck his cock in his mouth.’

‘Aye, that’s right, McCoy. This whole murder scene’s been arranged just to give you a fright.’

McCoy nodded over at the body. ‘How did we know he was here?’

‘Anonymous phone call into Central,’ said Murray.

‘From whoever did it?’

Murray nodded. ‘Who else? No other bugger would know he was up here.’

‘Sir?’

They turned. Wattie was standing there with a clear evidence bag. ‘One of the uniform boys found these.’ He handed the bag to Murray.

Murray took out his torch, switched it on and pointed it into the bag. Three used flashcubes, bulbs fizzled and spent, and two Polaroid backs, the cardboard left when you peel the picture off. He turned the bag and they could see the ghost photo on them. Reverse images of the man’s destroyed face.

‘Christ,’ said McCoy. ‘Pictures for later. Lovely. Might be fingerprints on them?’

Murray nodded.

‘What do you mean for later?’ asked Wattie.

McCoy made a wanking gesture. Wattie groaned.

‘Mr McCoy, nice to see you back.’

He turned and Phyllis Gilroy the police pathologist was standing there. Seemed to have some sort of tiara thing on under her Rainmate, pearls round her neck, bottom of a pink chiffon dress poking out beneath her black rain slicker.

‘North British?’ asked McCoy.

She nodded. ‘Mrs Murray was indisposed so Hector kindly invited me along as his partner. Unfortunately we didn’t get to stay very long. Had to leave before the turn. Moira Anderson. Pity, she has an excellent voice, I think.’

‘You look very . . .’ McCoy searched for the word. ‘Dressed up.’

‘I’ll take that as a compliment,’ she said, ‘of sorts.’

‘Did you have a look?’ asked Murray.

‘Indeed I did.’

‘And?’

‘Provisionally?’ she asked. As always.

Murray sighed. As always. ‘Provisionally.’

‘Gunshot to the front of the head, specifically the left eye. As you will have noticed, that had the effect of pretty much removing the back of the head. There is another gunshot wound to the left ankle which seems to be post-mortem. Other than that he’s been knocked around a bit, scratches and scrapes and cuts. And of course, the amputation of the . . .’

She hesitated for a second.

‘The penis.’ Carried on. ‘The words on his chest look post-mortem too but I’ll have to double-check . . .’

‘Why no clothes?’ asked McCoy.

‘That, Mr McCoy, is a question for you rather than me, I fear. However, were I to conjecture I’d say he wanted the BYE BYE on the chest to be on display, first thing one would see, but as I said it’s only conjecture. Now, if Hector will give us the go ahead I’ll get the ambulance boys to start packing him up?’

Murray nodded, and she walked off across the roof, gesturing to the ambulance men that they were good to go.

McCoy watched her go, looked at Murray and grinned. ‘Hector is it now? Didn’t know you and the esteemed Madame Gilroy were so pally.’

‘Secret weapon. She’s perfect for fending off the top brass. She’s cleverer, richer and posher than the lot of them put together. I just hide behind her and smile. Stops them pressuring me about Central.’

McCoy blew into his hands. He was freezing, driving rain had pretty much soaked him through. Icy wind blowing round the top of the building wasn’t helping much either. ‘Do we know who he is? Nightwatchman, something like that, maybe?’

Murray held up a clear plastic bag with a bloody wallet in it. ‘Don’t know, but this was sitting next to the body. Whoever did it wanted him identified quickly.’

McCoy took the bag off him, fished out the wallet, trying not to get too much blood on his fingers. He flipped it open, managed to read the name on the driving licence.

‘No,’ he said. ‘No way.’

He dug further in the wallet, found a folded-up bit of newspaper. He unfolded it. Read it. Couldn’t believe it.

‘Christ, it is. It’s him.’

He held up the newspaper. Murray peered at it, too dark for him to read. Got his torch out, pointed it at the clipping. Illuminated the headline.

DREAM DEBUT FOR NEW CELTIC SIGNING