Читать книгу Game Changers: Inside English Football: From the Boardroom to the Bootroom - Alan Curbishley, Alan Curbishley - Страница 8

Chapter 2 Player

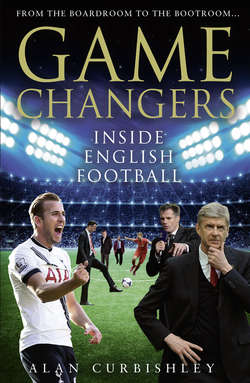

ОглавлениеHarry Kane, Mark Noble

When fans go to watch their favourite teams and see the players walk out onto the pitch before the start of a game they are probably unaware of the different paths those footballers may have taken to get to that point in their lives. Being a first-team player doesn’t just happen, and it certainly doesn’t happen overnight. It has usually involved years of dedication, years of having to prove themselves and years of having to cope with the ups and downs the game will inevitably throw at anyone who wants to earn their living as a professional footballer.

Becoming a regular Premier League player can now offer financial rewards beyond most fans’ dreams. Players are lucky to be playing in an era that offers these rewards, but they don’t just walk into a top club’s first team. There’s a very long road that they have to travel that will test them mentally and physically, and even when they are part of a first team, it’s up to them to keep proving themselves week in, week out. Very few players can afford to feel totally secure about their place in a team. Of course, you’d expect Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo to be the first name on the team sheet each week, but even they are not immune to injuries, and an injury can not only mean time out of a side – it can, in some sad cases, mean the end of a career.

Top players these days are the new rock or movie stars. They become household names, and are on the backs – and fronts – of newspapers. A lot of players get stick for the amount of money they earn and for not having the connection with the fans that players in earlier eras perhaps had. It’s true that some of them don’t do themselves any favours with the way they behave on occasion, but they are by no means the majority; a lot of players are hard-working, decent individuals who recognise how fortunate they are to be playing at a time when the game is awash with money for those who reach the top.

Our top division, the Premier League, has benefitted from all the big money, and there have been some big-name foreign stars who have graced the league and continue to do so. The temptation for clubs to widen their net when looking for talent has never been greater. The attraction of the Premier League means there are more than enough foreign players who are willing to play here, but that fact has also had a knock-on effect for young English talent, making it harder for our own youngsters to break through and reach the top. Later on in this book you will read about the dwindling number of English footballers playing in the Premier League, and one of the consequences of this trend is that there are fewer and fewer local kids who make it through to the first team with their local clubs and, more importantly, manage to stay there. In the past it was often the case that your club would have a few players in the side who had come through the ranks. They might even have been players who came from the same area you’re from. That sort of thing seems to be happening much less now, and it’s inevitable when you think of the footballing environment top clubs have to operate in. It’s sad in many ways, but it’s a fact of life.

So when you get players like Harry Kane and Mark Noble rising to the top, playing for the clubs they supported as kids and becoming local heroes, I think it’s worth hearing about just how they managed to do so, and the trials and tribulations they had to overcome in order to get there. They strike me as being similar in many ways. They are honest boys from ordinary backgrounds who had the drive, determination and inner-belief to make it into their respective first teams and stay there. It goes without saying that they also had to have talent in the first place, but talent will only get you so far – there are plenty of stories to illustrate how some very good young footballers don’t make it to the top.

I know Mark quite well because I was his manager for almost two years at West Ham, but until recently I had never met Harry Kane. Like lots of other people I’d watched his rise to the top with Tottenham and England during the past couple of years, and was delighted to see it happen. He seemed to be a class act both on and off the pitch, with the talent and character that would take him a long way in today’s game, and with that inner belief that helped him come through some trying times before he became the star name he is today.

‘It was tough at times,’ Harry admits. ‘I first started training with the first team when Harry Redknapp was manager, and you think you’re doing well and trying to get into the team, but in their eyes they’re probably not even thinking about playing you any time soon. Football these days, with more foreign players that are being brought in, as a youngster you can feel you’re on the cusp and then they might go and buy someone and you’re back training with the reserves. For me it was just a case of being patient. I went out on loan. The first couple of loans – at Leyton Orient and Millwall – were good, and when I came back from them I thought I might have a chance of getting a run in the team, but it didn’t really work out.’

Harry made his debut for the Tottenham first team in a Europa League match at White Hart Lane against Hearts five years ago and played a few more games in the competition for them. By that time he’d already had his loan spell with Orient and at the end of 2011 went on loan to Millwall. In the summer of 2012 Harry Redknapp left Tottenham and the club appointed André Villas-Boas in his place. A new manager presents a new challenge for any player because they naturally want to impress, especially if you’re a young, nineteen-year-old striker, as Kane was at the time.

‘I came back from the Under-19 Euros,’ he recalls. ‘AVB kind of said he wanted three strikers – two main strikers and another one – and he wanted me to be that third striker. I thought that would be perfect. I thought if I had a good pre-season I’d hopefully be in the squad for the Premier League games, maybe get some games and work my way into the team. But after pre-season I didn’t really get into the team. He said it was probably better if I went on loan, which was a kind of setback. They also bought Clint Dempsey on the final day of the transfer window, so that was his third striker, and from my point of view it was probably another year where I wasn’t going to be playing. And that’s when I went to Norwich on loan.’

It was supposed to be a season-long loan but it didn’t work out that way. As so often happens, Harry, like other players before him, had to deal with a season that produced some difficult times for him. He went to Norwich and got injured, breaking a metatarsal bone, which meant he went back to Tottenham for treatment before returning to Norwich. Then Spurs decided to recall him early from the loan spell, but after less than a month back at the club he was on his way again, this time to Leicester in the Championship for another loan period until the end of that season.

‘That loan started okay, but then I found myself on the bench and that was tough,’ he admits. ‘It was the first time I was living away from home and it was the first real time I hadn’t been playing. I was on the bench. My aim was always to go back as a Tottenham player and the loan was experience for me. But there were times when I was at Leicester that I thought, “I’m not even playing at Leicester. What are the chances of me playing in the Premier League any time soon?” There were doubts then that crept in, but I’m quite strong-minded and I thought to myself, “Look, be patient. You’re young and things can change in football so quick.” Even at that age I’d seen some careers go right up and then down. Some others had started slow and then come up, so I just knew I had to ride the wave and be patient.

‘The season after that, which was AVB’s second, I went on a pre-season trip to Portugal with the reserves and the first team went to Hong Kong, so I knew he wasn’t looking to put me in his plans that soon. The trip to Portugal was one of the best things that happened to me. I went with Tim Sherwood, Les Ferdinand and Chris Ramsey, got really fit and played a couple of games out there, then came back and had a really good pre-season. I surprised AVB and he said to me that he wanted to keep me there, but then they sold Gareth Bale and were buying player after player. From my point of view it was tough, because you’re doing well and thinking, “This might be my chance,” and then they get all that money and start spending it on new players. It’s another time where it tests your patience and how strong you are, how strong-minded you are. You could see all the players coming in, but I said to myself, “This is the season for me, I want to stay here and I want to prove that I’m good enough to be here. I don’t want to go on loan.” I didn’t want to just go, take the easy option and get a few games. I wanted to stay and battle it out – so I did, and it was the best I’d ever trained. I was on fire. I had other first-team players coming up to me saying, “You’ll be playing,” but I wasn’t getting any time. I was in the squad, but I was always nineteenth man. It was tough. I’d come home, talk to my family, talk to my agent. I’d think, “What else can I do? I’m the best player in training every day.”

‘My biggest fear was going on loan, and then someone getting injured and I’m not there. At the start of that season Emmanuel Adebayor was there, Jermain Defoe was there, Roberto Soldado had been bought and Dempsey was still there. AVB played one striker – you had four top strikers and they were big names as well. So never mind me not being happy to sit on the bench. None of them were going to be happy sitting on the bench! There were four strikers in my way, but I was adamant that I could get in front of them from what I saw in training. I knew that if I kept doing what I was doing, the older I got and the more physical I got, I was going to catch them up quicker than people thought. And that’s sort of what happened.

‘Adebayor wasn’t really getting in the squad, so it left Defoe, Soldado and Dempsey. Obviously, I’m not stupid. I know what it’s like when you’re at a big club. I know they have the choice of who they’re going to play – a £26 million player like Soldado, or me. I spoke to AVB about it. He was a nice bloke and I got on well with him, but he kept saying, “You’re doing well. Keep doing what you’re doing, you’re young, just keep working hard.” I’d heard that sort of thing before, but then things turn around quick, and it did that season. AVB left the job in the December and Tim Sherwood came in, who I’d spent a lot of time with. Him, Les and Chris came in, and I’d been with Chris since I was in the Under-15s and had a really good relationship with him. I was just coming back from a stress fracture of my back when Tim got the job, but I was obviously quite excited because it was a fresh start and Tim knew me. Whenever I’d spoken to him, he’d said, “You’re good enough to be in the team,” so I was excited. I was on the bench for a game at Old Trafford against Manchester United and he brought me on for the last ten minutes. I thought, “Here we go!” but although I got a bit of game time, even with Tim I struggled to get in the squad.’

At the end of that season Tim Sherwood was replaced by Mauricio Pochettino, who joined Tottenham from Southampton. I’d seen his Southampton team play and saw how he liked his sides to press high up the field. Tottenham by this time had sold Dempsey and Defoe, so when he first took over at Spurs my first thought was that Adebayor and Soldado would not be able to play the way he liked his striker to play. It just wasn’t their sort of game, and that fact eventually proved crucial for Harry.

‘When he came in I thought it was my chance,’ he admits. ‘There were only two strikers in front of me. I’d seen the way Southampton played, and thought, “That’s me.” I knew I suited his philosophy. I had a good pre-season – everyone was playing half a game, and I scored goals – but once again I couldn’t get in that Premier League team. I played in the Europa League and was scoring goals, but I couldn’t get in that Premier League side. I was getting minutes here and there, but then I came on in the game at Aston Villa in November and that was kind of the start of it.

‘I’ve spoken to the manager about what happened at the start of that season and he asked me, “Why do you think you weren’t playing?” I said, “I don’t know, but obviously Adebayor was a big-money player, and they’d spent a lot on Soldado.” He said that wasn’t the reason. He told me that he knew I was scoring goals and doing well, but he didn’t want to just throw me in ahead of Adebayor and Soldado and have people asking why they weren’t playing. So he gave them the chance to play. They weren’t doing what he wanted, so he brought me in. He said that Soldado and Adebayor couldn’t then knock on his door and say, “Why are you playing this young kid in front of me?” He gave everyone a chance to play, but he always knew that I was going to be the one that he wanted playing. Because for him there was no rush. It wasn’t like he’d come in and got six months to change everything. He knew he was building a team over two, three, four years. He’s a great manager, the best I’ve worked under. People will say I would say that because he gave me my chance, but it’s not that. It’s the kind of all-round person he is. He’s very smart. He’s brave. He’s not afraid of big-money signings, and he gets in and plays who he thinks is best. We’ve got a young team and I can only see us getting better. We’re moving to a new stadium in a couple of years, so the future’s very bright.’

Having finally made that breakthrough into the Tottenham side, Harry seemed to get better by the week, scoring goals for fun in that first season, getting thirty-one in all and twenty-one of them in the league, and taking seventy-nine seconds to score for England in his full debut against Lithuania. Not surprisingly he very quickly became a firm favourite with the Tottenham fans, with them singing the now-famous song about him, ‘Harry Kane, he’s one of our own’ – that seems to be exactly what he is and why the supporters can so readily identify with him. To go from the relative obscurity of being a squad player with Tottenham to being their main man within the space of a less than a season could easily have had an unsettling effect on a young player, but that’s not the case with Harry. He is a very down-to-earth individual who is both happy and grateful to be in the position he finds himself in.

‘I’m a normal person and a big football fan,’ he insists. ‘I have a good family, good friends and a good agent. I always wanted this dream and I’m quite level-headed. There were times when it was tough, but to be in the situation that I’m in now is what I wanted. What it’s about now is maintaining it, not taking my foot off the gas because I’ve got a nice house and I’m playing every week. I want to go on and win trophies. For me it’s always about getting better and better. But it’s different for me now, even walking down the street and people stopping you. Your life changes so quickly – and when you hit the international stage and you play for England, it doubles. But for me it’s always been about getting better. It’s having that inner drive and it’s never been about the money – it’s about winning trophies and playing on the big stage.

‘There are rich teams out there and they pay their youngsters a lot of money. You do see youngsters who get ahead of themselves and you think, “What have you achieved to be doing this or that, to be driving around in that car?” If you’re good enough and you’re playing and doing well, you’ll get more money than you could ever imagine anyway. You can’t, as a fifteen-, sixteen- or seventeen-year-old be thinking, “I’m going to get loads of money,” because to get that you’ve got to be doing well on the pitch. It’s common sense that if you perform on the pitch and get better and better, money’s not going to be a problem.

‘Things are different for me now to when I first made my debut. Back then you didn’t really know what to expect, walking out at White Hart Lane for the first time playing for the first team, and you want to impress and maybe you overdo things or try too hard. Now I’ve played plenty of games, and when I walk out there now I’m at home. It’s about getting experience as a young player, which is why I think the loans were important. I didn’t just come from reserve football to playing under the lights in a big stadium in front of big crowds.’

Having had such a good first season for Tottenham and at international level obviously meant there was pressure on him to perform right from the start of the 2015–16 season. There were comments and whispers about him possibly suffering second-season syndrome and not being able to turn it on again in the way that he had when he burst on the scene. Harry had to put up with mutterings about him being a one-season wonder from some people, and when he began the new season and failed to score in the league for Tottenham until the end of September there were whispers from some, questioning whether he was the genuine article. I never had any doubt that he was, and what impressed me about his play during that barren spell for him was his overall play for the team. He never hid or shirked his responsibilities, and because he has the ability to drop off and play as a number 10 he’s able to allow his teammates to go past him and can set up other people in the team. So even when he wasn’t scoring he was influencing the game.

‘It was always in the back of my mind – even at the end of that first season – that if I didn’t score for two or three games, at the start of the next one people would say, “Second season. He’s not going to do it again.” Sometimes it was difficult,’ he admits, ‘when you’re reading things maybe online or on social media, with people saying, “He’s not as good as he was last year. He’s not the same player.” But I knew I was still playing well; it was just the goals that were the difference. I was doing well for the team, I was working hard for the team, so for me not a lot had changed except for the goals. I stayed positive and it wasn’t like I was under pressure from the manager to score. He was happy with the way I was playing. I’ve always scored goals at any level I’ve been at, so I knew the goals were eventually going to come.

‘Then things clicked and I managed to score quite a few in a row. It was a good moment for me – to prove everyone wrong and show that it wasn’t just a one-season thing. I knew that I wasn’t going to let that happen, but I did have something to prove and I stayed positive. But it does hurt you when people say, “Oh, he’s not good enough. He’s rubbish. It was a one-off season.” It does hurt you – it would hurt anyone – but it gets that fire in my belly going and it makes you want to prove them wrong. When it did happen I wasn’t going to say, “I told you so.” I just got on with my business. I’d come home sometimes when I wasn’t scoring and I’d be angry. I’d talk to my girlfriend and she would say all the right things, and I’d talk to my family and they would tell me to keep going, but that’s what you need. You need to be able to let it out, and when things are going well you’re all there together enjoying it. It’s something I want to keep, and it’s important to me to keep it throughout my career. There are bumps along the way that you’ve got to overcome, and having people who are close to you is important.

‘A lot of people also talked about tiredness and having a rest after that first season, but I’m a player and I’d play every day if I could. In the summer when I went to the Under-21 Euros it was something I wanted to do for experience. It was the chance to go away in that sort of environment – the hotel life, the training, playing a game every three or four days – so for me it was getting experience for what was hopefully going to follow with England in Euro 2016. Obviously the Under-21 tournament didn’t go as well as we would have wanted, but it was good experience and I never felt tired. I think a lot’s down to the manager and staff at Tottenham, because they’re very good at knowing when the time’s right to have a rest and when to train hard. We’re probably one of the only clubs to do double sessions throughout the season, but the staff and management keep me fresh and healthy. It would take quite a lot to stop me going out and playing. I feel like if I didn’t play because of a little injury I’d be letting people down and letting the team down.

‘I want to play in every game, but obviously if the manager rests me and puts me on the bench he has his reasons. I would never say to him, “Look, I want to be playing.” It’s his decision and I go with it. When I’m on the bench I think about what it was like at Leicester – I’d be on the bench and used to think that if I got the chance to go on I’d have to change the game. You’ve got to have that mentality – to make an impact when you come on and make a difference.’

One of the things I’ve noticed with Harry’s goals is the way a lot of them come because he gets his shots off so quickly. He doesn’t take an extra touch that a lot of strikers do, and because of that defenders – and more particularly, goalkeepers – don’t have a chance to get themselves set. I wondered where he’d got the technique from.

‘That was Defoe,’ he says. ‘He was the best I’ve seen at that in training. He was unbelievable. We’d play little games or five against five, and he’d get the ball, touch and finish! He used to score so many goals by doing it. If defenders closed him down and got tight, he had the ability to skip past them. I think it’s important for a striker, especially in the Premier League, to get shots off early, because defenders will get back in time and block the ball, and keepers these days are so good they’ll see it coming and block it.’

Like all strikers, and despite his all-round team play, Harry lives for goals. His path to the top, and the way he had to persevere and believe in himself, should be an inspiration to youngsters out there who are trying to battle their way through and are suffering some inevitable knockbacks along the way.

‘I hope what happened with me can give younger players that drive and that goal to go and get in the first team,’ he says. ‘Things can change so quickly for you in football, and for me patience is a big thing. There are probably times when you think you should be playing in the first team, but being patient and not letting it get to you is a big part of it. I do see myself as quite an older figure at the club even though I’m still young. But we have a young team and a lot of younger players coming through. You can see times when they get frustrated, when they get left out of squads and things like that. I’ve said to a couple of them, “Just be patient, your time will come, you’ll get your chance. Just be ready.”’

Harry’s connection with the club and with the Tottenham fans is genuine and something that he is happy to have. There is nothing better for a fan than to see one of the club’s youngsters make it all the way to the first team and be successful, because so often over the years that has not been the case and, as I have mentioned, the competition for young English players to make it all the way to the top has never been fiercer. So it’s good to see a success story like Harry’s and it’s fantastic for the Spurs fans to know they are watching ‘one of their own’ who is delighted to be playing for the club.

‘I’ve been at the club so long, since I was eleven years old,’ he says. ‘I’ve been to games – I was a fan watching games before I was a player – and I know what it’s like to be a football fan. I’m a big football fan. I think the fans appreciate the way I work for the team and put in my all every game, and you get that connection with them. Obviously they sing the song about me, and I just try to give something back to them. Fans are a big part of football. If you don’t have fans you don’t have football. So I think it’s important you take time out for them. It’s got to work both ways – they come and support you, and you’ve got to support them as well. You have that connection and that feeling with the fans, where you probably wouldn’t want to go anywhere else. You have that good feeling. Every game they’re singing your name and cheering you on. Why would you want to go and start somewhere else? If you’ve got that connection, that’s what you want in football.’

Having that sort of connection with the fans was something I witnessed first-hand when I was Mark Noble’s manager at West Ham, and it was no surprise that his was the biggest-selling shirt in the club shop. Like Harry Kane, he had to go out on loan and then had the belief and strength of character to say no to another loan in order to battle it out and earn himself a place in the first team. That was when I first came across him as a young player.

‘I’d been out on loan at Hull and at Ipswich,’ he recalls. ‘The manager at the time was Alan Pardew and I was eighteen years old. I went up to Hull and didn’t enjoy it. I did my back in the first training session I had with them. I carried on and played some games for them, but I didn’t enjoy it. The next season I went out on loan to Ipswich and I loved that, and I remember coming in from a training session one day and seeing that West Ham had signed Carlos Tevez and Javier Mascherano and thinking, “Where has that come from?” I came back from that loan and went to see Pards in his office. He said, “I’m going to send you out on loan again,” and I said I didn’t want to go. If I’m honest, the team were in trouble and it looked like he was going to get the sack. So I thought, “I don’t want to go on loan for three months, he gets the sack, and then when I come back nobody knows who I am.” So I took a chance and stayed.’

Alan Pardew did get the sack, and I was the man who took over. Mark had played a handful of first-team games before I arrived but wasn’t an established first-team player. He impressed me when I got to West Ham – he was in my face every day, desperate to be in the team, and he trained the way he played, giving everything. I began to play him in the team as we successfully battled against relegation, winning seven of our last nine league matches, and Mark then became an established member of the first team during my time at the club.

‘I always believe the decision I made to say I didn’t want to go out on loan again saved my career at West Ham, for sure,’ he says. ‘That decision was probably the best I’ve ever made and I’ve now played more than 330 games for the club and I hold the record for Premier League appearances for them, as well as having been through some amazing times with them. I think what happens with so many players now is that they haven’t got the self-belief. They go out on loan, and the next minute they’re forgotten about. They might play in the Championship and forget about what it means to be a Premier League player. I think you can go out and you’re happy, but you sort of lose that will to say, “No, I’m going to play in this team.”

‘One of my proudest achievements as a player is that I’ve had five or six different managers during my time at West Ham, all with their different ideas and different ways of playing – and from different cultures – but I’ve started every season in their teams. I know I’m not the greatest player in the world, but I know I’m a good player. I know I’ve got ability, but I know my enthusiasm, hard work and commitment to playing probably outweigh my ability in some ways. I class myself as a good Premier League player who’s played a lot of games and knows what the league is about. When a new manager comes in to the club you have to reinvent yourself in some ways and think about how he wants you to play, and then get on with it. That’s where your mental strength and willingness to learn come in. That’s when you have to impress the manager and say, “Right, I’m going to be in your team.” I think that kind of thing is born in you, having that self-belief, and I’ve always wanted to play for the club.

‘I think it has a lot to do with how you’re brought up and where you’re brought up. I was born in Newham General Hospital, a golf shot away from Upton Park. I went to school in east London and used to go and watch games at West Ham before I ever played for them. I’ve seen loads of players with the natural ability to get to this level and play in the Premier League but who mentally can’t cope with what you have to do, especially once you get into the team. So to get there and stay there and to keep playing at that level, to overcome a bad game or a 3–0 loss, or getting abused by the fans, you have to be mentally able to cope with that – and not a lot of people can.

‘You speak to players now and a lot of them say, “You’ve got to get a move to earn the money, to get appreciated.” Obviously when I was young I wanted to earn money, like every young kid does when they’re a player, but I’ve always really enjoyed that fight, that challenge of saying, “They’ve bought him or him, but there’s no way he’s playing me out of the team!” I use it as motivation. I always think, “Right, it’s my spot and you’re not taking it.” You get some players out there and they don’t play and they’re fine with that, but I’ve never been able to enjoy not playing. To be honest, I’ve never really been able to enjoy life if I’m not enjoying football. It’s probably wrong, because at the end of the day it’s a job and I work for West Ham. It’s a great job, but if we lose on a Saturday everything’s affected for me. Everything. For a lot of players it doesn’t affect them, but it affects me – you just ask my wife. It affects the way you live, especially me. If I don’t play well or we get slaughtered, it’s horrible.’

Mark has been playing in the West Ham first team for ten years now, and the fact that he has maintained his place in the side under so many managers is testimony to how much each of them have rated him. His consistent performances make him one of the first names on the team sheet each week, and he has proved himself to be a quality player operating in one of the best leagues in the world. He has seen quite a lot of change in the game during his time at the club and believes that players like him may soon become a dying breed in the Premier League.

‘I talked to my teammate Aaron Cresswell last season and said that players like us – who are not really that fast, not really that strong, not really that tall and not really that athletic, but are good English footballers – we’ll be gone soon! The reason is that clubs can go and buy a foreign player for £2 million. If you look at me now, I’m twenty-nine years old and I might be worth, say, £8 million in the transfer market. So if a club were looking, would they spend that money on me or someone like me, or would they go abroad and get four players for the same price? There’s a much bigger pool for clubs to look at when they want a player now to the way things were even ten years ago. Probably ten or twenty years ago West Ham might have had a European scout. Now we’ve got scouts all around the world looking at players. No player who’s doing well goes unnoticed.’

Mark’s strong connection with the area the club are based in and with the fans has made him a firm favourite with them. But I know from personal experience that it isn’t always easy for local lads. I regularly used to go out for a meal with a couple of friends, Glen and Lee, who I first met when we were all apprentices. I was at West Ham, Glen was with Ipswich and Lee was at Chelsea. We’re still friends to this day, but when I was manager of West Ham and we were battling against relegation when I first took over, they told me they couldn’t go for one of our regular get-togethers because the restaurant we went to was in the heart of West Ham territory – and they knew the evening could be spoiled by me getting stick from fans! Mark has had to deal with that sort of thing throughout his career, but knows it goes with the territory.

‘I’ve got four or five close mates from school and they’re still mates now,’ he says. ‘When you’re brought up in the area then everyone you know is an East Ender and all their friends are from the East End as well. Sometimes someone will ask for twenty shirts to be signed and you can’t really say no, because they’re friends of friends – or you’ll get asked for twenty tickets for a match. Sometimes when it’s not gone right, and believe me there have been times at West Ham when it’s not gone right, you’ll see people in the street and they’ll be wanting to know what’s gone wrong and what’s going on at the club. I’ve always answered questions straight and I’ve never thought about not going somewhere because I might get pestered. It’s because people love their football so much that they want to know what’s happening. The game is so big now and every match in the Premier League is televised. So if you misplace a pass or make a mistake, that’s highlighted three or four times during the week.

‘I love being a footballer, and for me it’s a pride thing not a money thing. Some fans might see you lose 3–0 and think, “Look at the amount of money they’re on. I’d lose 3–0 every week for that amount!” But it’s not the money. If you care, like I do, it’s pride. I want to be able to walk down the high street and have fans say to me, “Well done, Mark. Good game on Saturday.” You want that instead of hearing them asking you what the hell is going on at the club and telling you to sort it out. It’s a pride thing, and the money doesn’t come into it for me. Of course, it’s great that I’ve got nice things now – and I’ve worked hard for them – but when we lose on a Saturday I don’t walk off thinking, “I get paid next month.” That doesn’t come into your mind. You think about the next game and you want to get a result from that game. You think about winning. You might lose four on the bounce, but then you get a win and you start thinking, “We’re all right!”

‘Once I’ve stopped playing and I look back at what I’ve achieved, I know I’ll be pleased. I’ve gone from being a little kid growing up in east London to being the West Ham player with the most Premier League appearances for the club, being involved in some big games for them like the two play-off finals, having a testimonial last season and captaining them in probably the biggest year in the club’s history as we move from Upton Park into the new stadium. I know I’ll be proud of what I did as a player.’