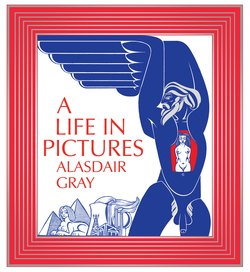

Читать книгу A Life In Pictures - Alasdair Gray - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Three: Miss Jean Irwin, 1945–52

ОглавлениеIN 1945 WE came home to Riddrie. In Wetherby I had played with other boys of my age, climbing trees, making dens in bushes, damming streams. I had a mental map of what was then a small market town on the Great North Road after it crossed the River Wharf, with the hostel my dad managed, racecourse to the east, the school and church on a cross-roads to the west. From walks and cycle rides I knew the countryside around it with the villages Bilton and Bickerton. I was now old enough to discover that Riddrie was one suburb of a huge smoky industrial city where my family was an unimportant detail – Glasgow was too big for me to mentally grasp.

Dad’s unsuccessful efforts to get a better job than cutting boxes on a machine, Mum’s worry about money and the future were also depressing. He found relief most evenings in unpaid secretarial work for the Camping Club of Great Britain (Scottish branch) and in weekend climbing and camping excursions on which he would have loved to take us all. Mum could no longer enjoy these. I could but usually refused to go because I hated being guided by his greater knowledge and experience of open-air life. I also had the excuse of very bad bouts of mainly facial eczema alternating with asthma attacks. These enabled me to stay at home in the small bedroom, at the small version of a senior executive’s desk my dad had made when his hobby was carpentry. Here I sat scribbling pictures and illustrating stories of magical worlds where I was rich and powerful, fantasies nourished by escapist literature borrowed from Riddrie Public Library, early Disney cartoon films, BBC radio dramatizations of Conan Doyle’s Lost World and H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds.

One day Mum put some of my scribblings in a handbag and took me by tram to Kelvingrove. She had read in a newspaper that Miss Jean Irwin held an art class on Saturday mornings in Kelvingrove, and I believe she hoped (though she never said so) that this class would get me out of the house and give me more friends. Children in it were supposed to be recommended by teachers, but my mum was an independent woman. A half-hour tram ride brought us to Kelvingrove, not yet open to the general public, but she swiftly got admission from an attendant who explained where to go. We went up broad marble stairs and along to a marble-floored balcony-corridor over-looking the great central hall, and I heard exciting orchestral music. At the top of more steps we saw twenty or thirty children busy painting at little tables before very high windows, painting to music from a gramophone, as record players were then called. I drifted around looking at what these kids painted while Mum showed my scribbles to Miss Irwin, who let me join her class.

Miss Irwin’s class , circa late 1940s

For the next five years Saturday mornings were my happiest times. This once-a-week sense of unusual well-being partly came from dependence on appliances like those in most British homes which, apart from the lighting, were mostly pre-electric. Our hot water taps drew on a tank behind the coal fire that warmed our living room. Baths were not taken casually and Friday was my bath night. Mum washed clothing in a deep kitchen sink, rubbing it a piece at a time on a ribbed glass panel in a wooden washing board, squeezing water out by passing it with one hand through a small mangle (which we called The Wringer) into the shallower sink, while turning with the other a handle that made the cylinders revolve. Bedclothes were then hung to dry on our back green clothes lines, other clothing on the kitchen pulley or a clothes horse before the living-room fire. After that she ironed them. Washing machines only became common in Britain halfway through the 1950s. Mum may have worked hard enough to give me a change of clothes twice a week, but I only remember how fresh newly laundered socks, underwear and shirt felt when I dressed on Saturday morning.

If the day was warm enough to go without a jacket I felt the whole city was my home, and that in Kelvingrove I was a privileged part of it. The art class children came an hour before the public were admitted, I was always earliest and could therefore take the most roundabout way to the painting place, starting with a wide circuit through the ground floor.

I first turned right through a gallery with a large geological model of Strathclyde near the door. It had a pale blue river, firth and lochs, and layers representing rocks painted to show how the valley and hills had been laid down in prehistoric times – pink sandstone predominated. Beyond were glass cases of fossils, including an ichthyosaurus, and uncased models. The tyrannosaurus was most impressive, and a great ugly fish with two goggle eyes near the front of his head instead of one each side, and big human-looking buck teeth. I left that gallery by an arch under the skull of a prehistoric elk with antlers over six feet wide.

The Three Wise Men , 1950, ink and gouache on paper, 41 x 51 cm

Then came modern natural history, the shells and exoskeletons of insects and sea-beasts, a grotesque yet beautiful variety showing the unlimited creativity of the universe. Some I hardly dared look at and would have preferred them not to exist. A spider crab had legs splayed out as wide as the antlers of the elk. Then came stuffed birds and animals in cases with clues to their way of life. I seem to remember a fox bringing a pheasant’s wing in its mouth to small foxes under a shelf of rock or under a tree root. Big animals were in a very high gallery behind large glazed arches. An elephant with its young one, a giraffe and gazelle had a painted background of the African veldt; an Arctic scene had walrus, seal and polar bear with fake snow and ice floes. A Scottish display had stag, doe and fawn, capercailzie and grouse among heather.

I have no space to describe my delight in the sarcophagi, ornaments, carvings and models of the Egyptian gallery – the splendid model samurai seated in full armour before the ethnography gallery with its richly-carved furniture, weapons and canoe prow from Oceania and Africa – the gallery full of large, perfectly detailed models of the greatest ships built on Clydeside. The ground floor displays assured me that the world had been, and still was, full of more wonderful things than I could imagine for myself.

After these wonders there was relief in the long, uncluttered floors of upstairs galleries in one of which our art class was held, but I always approached it through as many others as possible, so became familiar with the paintings on permanent display, though my preferences were distinctly juvenile. I loved two huge Salvador Rosa landscapes with biblical titles (one of them The Baptism in the Jordan) showing rivers flowing between rocky crags overhung by wildly knotted trees. I wanted to jump into this scenery and play there when the tiny figures of Jesus, saints and apostles had cleared out.Noel Paton’s The Fairy Raid delighted me too by mingling the Pre-Raphaelite details of a moonlit woodland with several sizes of supernatural races, from courtly fairies almost human in scale down through dwarves and goblins to elves smaller than toadstools. In those days there was a whole wall of Burne Jones paintings, at least four, showing the adventures of Perseus which I had read in Kingsley’s The Heroes. In 2008 the only one exhibited shows Danae standing sadly while behind her the brass tower is built for her imprisonment. When 17, on a visit to Glasgow City Chambers, I saw the rest on the walls of a corridor, so Glasgow town councillors still enjoy them or they are in storage. I admired the glowing detail of Dutch still lives but did not know why people who could enjoy real fruit, flowers et cetera wanted pictures of them; nor did I see the beauty of Rembrandt’s butchered ox hanging in a cellar, and would likely have agreed with Ruskin that Rembrandt painted nasty things by candlelight. Twenty years passed before I saw that a great draftsman and equally great colourist had painted that ox in a range of subdued tones far beyond my capacities.

Scylla and Charybdis, 1951, gouache on paper, 36 x 28 cm

Young Boy and Paint Box , 1951, ink on paper, 33.5 x 25.7 cm

What of the art class and its teacher? Jean McPhail, a fellow pupil in those days, describes her thus: Jean Irwin was an unmarried woman, belonging to the World War One generation which lost its men on the battlefields of Europe. Early in her career she became deeply interested in developing the creative talents of children and she set up and ran a free art class on Saturday mornings for children, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. I did not know that anyone in the class was disadvantaged, but like every teacher whose help I appreciated she gave me materials and let me do what I liked with them. After the first two classes I cannot remember painting any subject she gave, unless she suggested a Christmas nativity scene, thus inspiring the picture of the three wise men, which shows my cynicism about wisdom when it beholds a miracle. She may also have suggested my ink drawing of the small boy at a desk facing mine. I tackled any theme that excited me, painting free-hand in poster paint without a preliminary sketch, or else making an ink drawing and tinting it with watercolour. Craving miracles and magic I illustrated episodes from Homer’s Odyssey, Greek legends and the Bible and am sorry to have lost pictures of Christ walking on water, Penelope unweaving, Circe making pigs of her guests and a Jabberwock unlike Tenniel’s. I drew and painted with a freedom I have hardly ever enjoyed since. Soon each new picture had a difficult beginning, starting with my efforts to unite Beardsley’s crisp black and white areas with Blake’s mysteriously rich colours. In the library of Dad’s pal Bill Ferris I found a book of Hieronymus Bosch’s pictures in colour, and was entranced by his Hells, and sinister Eden, and huge Garden of Earthly Delights. From then on any state bordering on Hell or Paradise fascinated me as a pictorial subject.

In taking my prolonged private excursion through the galleries to the class one morning I found three or four upstairs rooms hung with all the greatest paintings and prints of Edvard Munch which I have since only seen in books. Munch painted Hell in the rooms and streets of Oslo, a city I saw was very like Glasgow, where very often the richest colours were in sunset skies. Munch, like adolescent me, was obsessed with sex and death. All his people, even those in crowds passing along pavements, looked lonely, all the women seemed victims or vampires. His white suburban villa, shown at night by street lighting, was appallingly sinister but not fantastic. He proved that great art could be made out of common people and things viewed through personal emotion.

The City: Version One , 1950, gouache on paper, 42 x 30 cm

Glasgow Art Gallery and Museums Exhibition Poster , 1952

Two Hills – originally called The City – combined parts of Glasgow that had come to excite me. I loaded the nearer hill with a kirk, school, tenements, towers I had seen on Park Circus, and tied them by a railway line to a further hill with a housing scheme beneath a dark factory based on Blochairn Iron Foundry near Riddrie. In those days the soot-laden skies over Glasgow on moist, cold, windless days often seemed like a grey ceiling, with the sun an orange or crimson disc in the centre. (In the autumn of 1951 for several days a pair of sunspots were visible on it.) My Two Hills city picture, painted freely in poster colour, led to my only disappointment with Miss Irwin. She wished to reproduce it on the cover of the class yearly exhibition catalogue, and before it was photographed for reproduction a friend persuaded her to repaint the foundry roof so that it appeared seen from above like smaller buildings before the chimney stacks. This stopped the angle of the dark foundry roof sloping toward the sun and towers beyond, ruining the composition. I had combined two different perspectives, sometimes called viewpoints. In the 15th century Ghiberti and Donatello invented a perspective ruled by a geometrical vanishing point, since when most western artists before the 20th century found it useful. Good ones still made pictures combining many views that did not conform to single vanishing point perspectives, while ensuring most verticals and horizontals did; but academic art teachers taught the rule as if it should never be broken. At Whitehill, my ordinary day school, schoolteachers had taught me that rule without insisting on it. Later, at Glasgow Art School, I met teachers of painting who did – they belonged to a late 19th-century academic tradition that urged everyone to paint like Velasquez with some early Impressionist freedom of brushstroke. One of them thought modern art had started going wrong with Cézanne’s still lives, which flagrantly broke the single viewpoint rule – he had not noticed the landscapes behind the Mona Lisa did so too, and that the ceiling and floor of the room where Jan Arnolfini and his wife stand have different vanishing points. In the Two Hills city picture I had combined different vanishing points instinctively. From then on I did so deliberately. The final version of the picture is the result of two reworkings, made years later by repainting some areas and taming most by drawing round them in ink.

The City: Version Two , gouache, pen and ink on paper, 1951, 42 x 30 cm

Seeing how much she had shocked me Miss Irwin apologized, and was too good a friend for me to bear a grudge. She lent me a big book with colour plates of work by the great Flemish masters which delighted me as much as the visions of William Blake. How different they were! Blake’s men and women are gods and goddesses acting in mysteriously colourful universes lit by impossibly huge suns, and enact glorious, sombre or terrifying mental states. Blake, like Michelangelo his teacher, thought elaborate clothes and furniture were devices commercial painters (like Sir Joshua Reynolds) used to flatter wealthy patrons. I agreed with him before I started enjoying the well-lit landscapes and rooms of the Van Eycks, and Van der Weyden and Memlinc with floors of beautiful tiles, well-laid planks and richly-woven carpets, yes, and panelled walls and carved furniture, richly-woven tapestries and views across gardens and bridges to houses and towers of grandly built cities. The people occupying these spaces usually wore rich robes, but often had the careworn faces seen even among prosperous citizens in a big city. The great Flemish painters were then portraying a mercantile society in which even the wealthiest folk appreciated how the goods they enjoyed were made. The separation between owners and craftsmen was not the gulf it became in the time of Rubens, whose main patrons were monarchs. The Flemish masters taught me that anything or anyone in the world, carefully looked at and drawn, is a good subject for art and therefore (as I still believe) beautiful. The artists of the Sienna and Florence republics could have taught me the same, but I liked the ordinary-looking Flemish folk more than the graceful Italians. Study of Van Eycks’ reproductions left me knowing that every detail of furniture and ornament in a room can appear beautiful if painted with a loving care that, years later, I brought to some pictures of domestic interiors, but only had time to complete a few of them as I wished.

Jonah in the Fish’s Belly now only exists in a black and white photograph, though the original was an ink drawing tinted with watercolour. I wanted to emulate Blake’s Book of Job illustrations by also making a biblical book one of mine, so naturally I began by reading the shortest, and was delighted to find the Book of Jonah had less than three pages, and was the only Old Testament book where God shows himself both merciful and humorous. The photograph was reproduced in the Glasgow Evening Times newspaper above the caption, Artist Alasdair’s Whale of a Picture, giving me a taste of that intoxicating publicity which turns stale as fast as it fades.

Jonah in the Fish’s Belly , 1951, pen and watercolour on paper, photograph of original work, now lost, 42 x 30 cm