Читать книгу Why Scots Should Rule Scotland - Alasdair Gray - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

THE GROUND OF ARGUMENT

READERS WHO LIVE in Scotland but were born elsewhere may feel threatened by the title of this pamphlet; I must therefor explain that by Scots I mean everyone in Scotland who is able to vote. This definition excludes a multitude who live and vote abroad yet are Scottish by birth or ancestry, yet includes many who feel thoroughly English yet manage Scottish farms, hotels, businesses, industries and national institutions. It includes second or third generation half-breeds like me whose parents or parents’ parents were English, Irish, Chinese, Indian, Polish, Italian and Russian Jewish. It includes seventy-two members of parliament who mainly live and work in London and some absentee landlords who occasionally visit ancestral Scottish estates to shoot, hold family parties and vote. This book is aimed at all voters north of the Solway–Tweed boundary because, whether born here or recently arrived, it is they who should elect the government of Scotland. But they don’t.

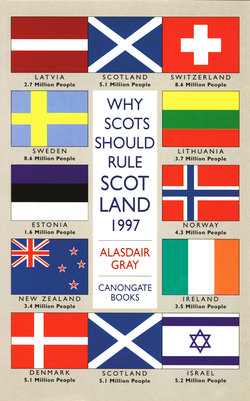

I argue that by being in Scotland you deserve a government as distinct from England as Portugal from Spain, Austria from Germany, Switzerland from the four nations surrounding her. My argument is not based on differences of race, religion or language but geology. Landscape is what defines the most lasting nations. The big rice-growing plain of eastern Asia explains why the Chinese nation is the largest, most peopled and most ancient. Another highly self-centred nation was made possible by successive layers of limestone, chalk and clay forming a saucer of land with Paris in the middle. The Baltic Sea explains why such close neighbours as Norway, Sweden and Denmark have different governments though similar languages and populations which, if united, would be less than two fifths of England’s.

But no natural barrier can contain human curiosity, greed and desperation, so invasions and migrations have kept national boundaries expanding and contracting like concertinas. Roman geographers were first to map two big islands they called Britannia. They saw that, like Gaul, these were naturally divided into three parts which they named Albion, Caledonia, Hibernia. Albion was the south part of the biggest island: very woody and marshy yet offering few natural barriers to the march of the Roman legions. The tribes of Albion combined to repel the legions and were defeated. South Britain got planted over by Roman camps joined to each other by well-built roads and to Londinium, Britain’s first capital city. The biggest camps were sited in the most fertile places and at the best places to bridge the rivers. They grew to be the centres of towns which thrive to this day: Bath, York, Lincoln, Carlisle and every city whose name ends in chester or caster. The geography which helped the Roman occupation explains why the English Catholic and Protestant Churches have been officially ruled from Canterbury since AD 596; why the English state has been ruled from London since 1066, and has two ancient universities in what were market towns near the capital.

The legions later marched into Caledonia. The Pictish tribes here also combined to repel them and were defeated, but Caledonia was hard to keep and expensive to administer. Firths, sea lochs, chains of high moorlands and mountains made north Britain like a cluster of big islands jammed together in the east and coming apart in the west. Soil which could be cultivated lay in districts cut off from each other. The natives, though defeated, had secure wildernesses from which to counterattack. As Edward Gibbon put it:

The native Caledonians preserved their wild independence for which they were not less indebted to their poverty than their valour. Their incursions were frequently repelled and chastised, but they were never subdued. The masters of the fairest and most wealthy climates of the globe, turned with contempt from gloomy hills assailed by the winter tempest, from lakes concealed in a blue mist, and from cold and lonely heaths, over which the deer of the forest were chased by naked barbarians.

The geography which helped to repel Rome explains why the Scottish Church, Catholic and Protestant, had no locally based archbishop or single official to command it; why Scotland had no single capital city before James VI emigrated to London in 1605, but four ancient universities in very different cathedral towns.

Gibbon says the Romans calculated the number of legions and ships they would need to conquer Hibernia but decided conquest there would also be too much trouble. The only part of that island convenient to the British mainland was the north-east corner nearly touching Caledonia. This explains why the only part of Hibernia now belonging to mainland Britain is the north-east corner, despite seven centuries of trying to subdue the whole island by frequent doses of indiscriminate massacre. The strangest thing about Hibernia is that Christianity took root here outside the Roman enslavement system and produced a highly literate monastic culture among small tribal kingdoms. The Hibernian tribes were called Scots in those days. Caledonia belonged to the Picts, though Norwegians sometimes occupied her northern and western shores.

It sometimes seems that every nation in Europe has had a spell of bossing others in defiance of natural boundaries, yet every empire is at last undone by the appetite for home rule and inability to rule ourselves well while bossing neighbours or foreigners. The Roman legions were returned to Italy in AD 404 because their slave-based empire was being attacked by nomadic tribes out of northern Asia. The Britons of Albion were almost immediately raided by Scots from the west, Picts from the north and German pirates from the east. Am I boring you?

PUBLISHER: (apologetically) The reader may be wondering how this ancient history helps the argument. You began by saying Scotland’s geology – the lie of the land – made her a different nation.

AUTHOR: It does, but like every other European land a great mixture of folk has poured into this irregularly shaped national container, a mixture to which people still add themselves. I am partly writing to persuade incomers to think of themselves as Scots by explaining why earlier incomers came to think so. The force that pressed or stirred a mixture of races here into a self-governing nation was often trying to shake it apart. That force was so often English that I cannot start my argument without saying how the English came to south Britain and Scotland to the north.

PUBLISHER: But in this size of pamphlet the result will be a kind of children’s history!

AUTHOR: I hear that nowadays many children and adults too have been taught little or nothing of history. It is adults I want to teach so here goes.

When the Romans left south Britain it was almost immediately raided by Scots from the west, Picts from the north and pirates from the east. The pirates were pagans from north Germany where they had farmed land in forest clearings, defended their crops with their swords and worshipped Thor and Woden. Pressure or example of the nomad invasions was moving them westward, so Britons invited them in to help expel the Picts and Scots. They expelled them so completely that in two centuries the natives of Albion had also been killed, enslaved or expelled into Cornwall, Wales and Strathclyde. These settlers eventually called themselves English, and the completeness of their conquest is astonishing if we recall that the folk they conquered were descended from builders of Stonehenge and tribes the Romans had not easily defeated. The explanation is that by finally submitting to the Romans (who historians consider a civilizing people despite their use of torture and massacre as public entertainments) the Britons grew too weak to preserve their own culture.

The English had little use for the Roman towns and military strongholds, thinking them causes of slavery. They lived in self-supporting farm communities ruled by councils of elders. When a warlord was needed for defence the elders joined neighbouring councils to elect a king. Kings were continually needed. As the settlers drained marshes and cleared forests the land attracted more Germans and Scandinavian invaders. Soon England contained six warlike pagan kingdoms with Northumbria one of the greatest. It spread up the east coast from the Humber, and the fewness of natural barriers made it possible for Northumbrians to occupy the most fertile part of Pictland up to the Firth of Forth. That is how the English language entered Caledonia.

While Britain was being Anglicized from the east some Scots sailed from the top right-hand corner of Hibernia and made a kingdom in the western islands and peninsula of Argyll. This new Scottish kingdom had Christian priests who read, wrote and built upon Iona the first British monastery outside Ireland. For five centuries Scottish, Irish and Norwegian kings were buried there. Priests trained in Iona brought Christianity to Picts in the east, Strathclyde Britons to the south, thus helping the Scots kingdom to spread through all these lands, though conquest, intermarriage, alliances against English and Scandinavian invaders also helped. In 846 a Scot ruled all Caledonia except the Northumberland part south of the Forth. Gaelic speakers called the Firth of Forth the English Sea because it separated them from Sassenachs.

It is good to know that language difference did not stop Scottish missionaries entering England and Christianizing it through Northumbria while the missionaries of Pope Gregory were doing that from Canterbury. The first vernacular poem in English literature, Caedmon’s Genesis, was dictated in a Northumbrian monastery founded by Gaelic monks. Which proves that different cultures can combine creatively.

PUBLISHER: Fascinating, perhaps. Is it relevant?

AUTHOR: Yes, because I can now explain why the English north of the Tweed became Scottish. They were driven to it by an oppressive new government centred on London. This turned them into defenders of a frontier which again separated different governments though not different languages. These English helped to make Edinburgh a Scottish capital city.

PUBLISHER: Do you hope that the English who have recently settled in Scotland will help to do the same?

AUTHOR: Yes. Scotland needs all the help she can get, The though London rule has not quite reduced her to the Ground state of Britain under Rome.