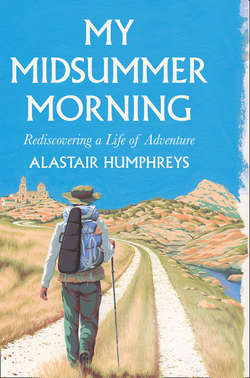

Читать книгу My Midsummer Morning - Alastair Humphreys, Alastair Humphreys - Страница 17

Into Spain

ОглавлениеI SAT ON THE harbour wall, gritty and warm, with my face tilted to the sun. Sea salt and engine diesel in the air. Halyards clanking and gulls circling. Back in 1935, Laurie’s ship docked in Vigo, a quiet corner of northwest Spain. Now I was here, too, at last. It was the first meeting of our paths since I had drunk in Laurie’s old village pub, the Woolpack, while dreaming of this trip. I envied how vivid this arrival must have been for Laurie, setting eyes on abroad for the very first time. ‘I landed in a town submerged by wet green sunlight and smelling of the waste of the sea. People lay sleeping in doorways, or sprawled on the ground, like bodies washed up by the tide.’

Here we go again, I thought: the start of an adventure. It had been far too long since the last one. I remembered the familiar belly-mix of nerves, melancholy and anticipation. After all the turmoil I had been through, I was jubilant that this was actually happening. I had thought these days were over. Laurie exclaimed, almost in disbelief, ‘I was in Spain, and the new life beginning. I had a few shillings in my pocket and no return ticket; I had a knapsack, blanket, spare shirt, and a fiddle, and enough words to ask for a glass of water.’ I had less money than Laurie, but more Spanish.

I picked up my rucksack and set off to explore Vigo. Graceful buildings flanked broad shopping streets, wrought-iron balconies on every storey. Meandering narrow alleys were hewn from rougher blocks of stone. A pail of water sloshed like mercury across the cobbles from a café opening for business, and I breathed the scent of geraniums. The waiter placed ashtrays on the wine barrels used as tables. Even after 20 years of travelling, I still cherish first mornings in a new place when every detail is fresh. Laurie described it as the ‘most vivid time of my life, the most free, sunlit. I remember thinking, I can go where I wish, I’m so packed with time and freedom.’

It was mid-morning, but Spain still slept. The streets were so quiet that I said ‘Buenos días’ to each person I passed. I climbed up to Vigo’s old fortress and peered down from its mossy walls. Terracotta rooftops jumbled higgle-piggle down to the harbour. Wooded hills curved green embracing arms around the blue bay, sprinkled with islands. Earlier, boatloads of carefree beach-goers had departed for those islands, laden with picnic baskets. I had watched Africans trying to flog them sun hats, their wares spread on tarpaulins for ease of fleeing should the police appear. I sympathised with the urgency of their hustle, the immigrant’s need to be enterprising. Like them, I had no money. I had been hard up before, but I’d never had nothing until today. Unlike the hat sellers, however, I was voluntarily penniless, so any comparison was absurd. I had a passport and permission to be here. At sunrise I had piled the last of my money into a small pyramid of coins on a park bench and walked away. I wished that I had bought a sun hat instead.