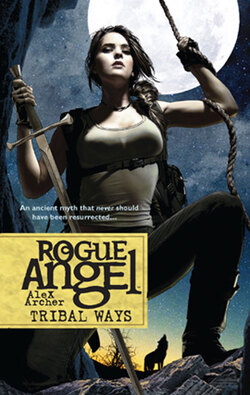

Читать книгу Tribal Ways - Alex Archer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеStanding in the open door of the RV with a mug of coffee steaming in his hand Paul Stavriakos cursed the freezing wind and wondered why he’d ever moved to the Great Plains.

“Either go or stay, but shut the damn door,” Allison York called from the bed. “That wind is freezing.”

Paul sighed and stepped down to the grass, still dry and tan from winter. He shut the door behind him. The wind howled around him.

Dawn was still a drizzle of red along the horizon. Clouds hid the stars overhead.

The land was all tilted planes. It was flat, in a way, but flat that tipped this way and that in big plates furred in yellow-brown grass. There wasn’t much relief; but it was deceptive land, with more hollows and heights than first struck the eye.

“Not enough to cut the damn wind, though,” he muttered to himself.

Lights appeared in the trailer that Donny Luttrell shared with TiJean Watts. The battered Toyota pickup with the camper shell belonging to Dr. Ted Watkins from the State Archaeological Division was rocking on its suspension more than the wind’s buffeting would account for. Paul hoped he was pulling on his jeans. The muffled swearing coming from inside seemed to support that thesis.

“Ever wonder why those old Indians picked a miserable spot like this to make their camp?”

Paul turned. Eric James was swinging off the back of his old buckskin gelding. He wore a sheepskin coat and a battered felt cowboy hat. The hair hanging in thick braids to either side of his head was gray as slate. The wide face between, the color of Oklahoma clay, had a tough and weathered quality but was barely lined. A full-blooded Comanche and full-time rancher, he owned the land where they stood.

He returned to his saddle for a moment, then turned back to Paul. He held white bags with a colorful logo in each hand.

“Brought doughnuts for you kids,” he said. “Hope you make decent coffee. Wasn’t carrying that in my saddlebags.”

Paul smiled. It felt as if ice was cracking off his face. The digging season seemed to start earlier each year. The ground wasn’t fully frozen. That was about all you could say for it.

Then again, he thought, it’s getting harder and harder to beat the protestors out here. Digging in colder and worse weather was one way of keeping them at bay as long as possible. Even so, they’d be out there with their signs and their shouting as soon as the day warmed up.

The trailer door opened. TiJean started down the steps wearing jeans and a T-shirt. He let out a yelp and popped back inside like a startled prairie dog. The door banged behind him. A second-generation Haitian from Miami, he didn’t quite get winter. Even if it was supposed to be spring on the Great Plains.

Like an unlovely butterfly from its cocoon Ted emerged from his camper. Unlike their host his face looked as if each of his fifty years had stomped it hard on the way out the door. He was skinny, with long dark-blond hair hanging out from his grimy Sooners ball cap, white stubble sticking out of his long chin and gaunt cheeks. He wore a drab plaid lumberman’s jacket. He completed his ensemble with faded blue jeans over pointy-toed cowboy boots.

“Another lovely day in western Oklahoma,” he muttered. “Christ.”

Paul winced as the older man unwrapped a piece of gum and popped it into his mouth. Ted was trying to quit smoking. Apparently gum was his designated substitute crutch.

Allison started out from the RV. Like the trailer it was owned by their employer, the University of Oklahoma at Norman. Unlike the trailer it was at least relatively modern. Since Paul and Allison were the assistant professor and graduate student on the dig, they claimed it by right of rank. Allison had a red wool knit cap pulled down over her long, straight blond hair and a white Hudson’s Bay blanket with big bold stripes of blue, yellow, green and red wrapped around her slim frame. Gray sweatpants showed below the bottom of the blanket above fleece-lined moccasins.

“Hey, Ally,” Paul called softly. “Could you make more coffee?”

He didn’t speak loudly, partly out of consideration for Allison, but mainly to keep his own head from cracking open. They probably shouldn’t have drunk quite so much last night, he thought. Indeed, they shouldn’t have been drinking inside the RV at all, since it was contrary to university policy.

Not that it’s the only rule we’re breaking, he thought. And what the hey? We have proud archaeologist traditions to uphold.

Allison scowled. The spanking of the cold wind was making her cheeks red and her blue eyes water. “Why me?”

“Because you’re still mostly inside where it’s warm,” he said, “and we have the only coffeemaker that works.”

“Chauvinist,” she said. “Did your girlfriend who’s coming to visit make you coffee?” She turned and went back inside, banging the door.

“She’s not my girlfriend,” he shouted at the door. “She’s just an old friend.”

Actually, Annja Creed was a young friend. She was a year or two younger than Paul. They’d met on a dig four years ago. Sparks had flown; the fire they kindled flamed up and flamed out. The end.

Now she was a semifamous cable-TV personality and globe-trotting archaeologist, coming out at his request to touch bases and look the dig over. Inviting her hadn’t even been his idea. It had been at the department’s request, in the probably unrealistic expectation that the resident expert on Chasing History’s Monsters might bring some good publicity their way.

“Women,” Donny said. He had emerged from the trailer to stretch and yawn, like an outsize nearsighted cherub with his dark curly hair and beard, his thick-lensed glasses and his belly sticking out between his green-and-white University of North Dakota T-shirt and sweatpants. He was a cold-weather guy and liked to show off his indifference to low temperatures. He wore sandals on otherwise bare feet. “You can’t live with them, you can’t—”

“We Numunu have an old tradition,” Eric said, interrupting him, using the Comanche word for his people. “We kill anybody says a cliché. Scalp ’em, too.”

Paul tried not to wince. Native Americans on campus usually believed, or at least said, all the right things. Outside the university those he met almost to a man and woman defiantly called themselves Indians and expressed contempt for political correctness in any form. You just had to get used to it. And for what it was worth Eric seemed genuinely friendly.

For one thing he let them dig his land—invited them to, when he accidentally unearthed the paleo-Indian site—in the face of rising rumblings of opposition from some of his people. For another he brought doughnuts. Even if they were bad for you.

Paul looked to Eric. “Really nice of you to be okay with us diggin’ up your ancestors, dude.”

“Not my ancestors,” their host said. “We didn’t live here then. Either we or the Kiowa ran off the people whose ancestors these were around three hundred years ago.”

He shook his head. “Well, one good thing about this damn cold wind—it’ll keep the professional Indians inside by their space heaters for a while. As much money as I give to the Nation every year the loafs-about-the-fort got nothing better to do than send me death threats and try to trespass so they can picket me on my own land.”

“Are you crazy, man?” TiJean’s voice, muffled by the layers of clothing he had donned before venturing forth again, rose perilously near to cracking. He was a freshman, only nominally out of adolescence. “Why don’t you got nothin’ on your feet?”

He was staring in horror at his roomie’s feet.

“Jesus, TiJean,” Donny said. “What, are you dressed to scale Everest?”

“For Sweden,” Ted added. The Floridian undergrad wore a blue-and-yellow parka with the fur-clad hood over his head.

Allison emerged from the RV bearing a tray with a pot of coffee and an assortment of chipped and colorful mugs. “All right, you big, strong, helpless men. The woman comes to the rescue.”

“Ah,” Ted croaked. “The stuff of life itself!”

Allison held the tray while the rest crowded around.

“Best leave some for me,” she said ominously, “if you don’t want to wind up wearing it. Whoa, does anybody hear a hissing?”

“Wow! Doughnuts!” Donny exclaimed, his eyes belatedly lighting on the two paper bags Eric had left on the grass.

“Yeah,” Paul said after a beat. “I do. Strange.”

Midway to the doughnuts Donny froze. “Don’t tell me there’s a snake?”

TiJean crowed laughter. “Who’s a wimp now, Eskimo Boy? Afraid of a little bitty old snake.”

“Whoever heard a snake hiss that continuously?” Allison asked.

“Or that loud, to hear it over this wind,” Paul said.

“Wait,” Donny said. “Did you guys see a shadow move? Off there to the left—”

“Shadow?” Paul said, feeling an inexplicable chill that had nothing to do with the wind.

“Yeah,” Allison said. “I thought I saw something out of the corner of my eye. Like a dog or something.”

“Shit,” Donny said, “that’d be a big dog.”

They were all turning and staring around. Paul felt a little woozy. Maybe he was turning too fast, getting dizzy.

“We should all chill,” he said. Then he noticed that Eric James had drawn the slab-sided .45 automatic he wore on his hip and was holding it two-handed with its muzzle tipped toward the unfriendly sky. His face was the consistency of stone.

“This is starting to freak me out—” Donny began.

Allison’s scream, sharp as glass, made Paul spin toward her. As he did something hot splashed across his face.

For a moment he thought she’d thrown scalding coffee on him.

Then the darkness hit him.