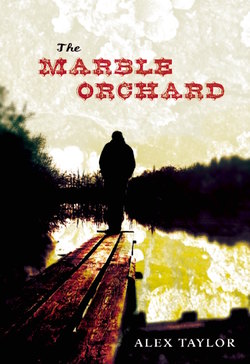

Читать книгу The Marble Orchard - Alex Taylor - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеII

WEDNESDAY

A damp morning. Rain had begun in the deep of the night and fallen steadily until dawn and at sunrise scraps of mist lay in the bottom country like shorn husks. The Gasping flowed quick and sudsy, its brown churned waters carrying driftwood and other debris downstream, crossties and bridge timbers, stray john boats and car doors, milk jugs and paint cans. There were strange catches in the locust trees, tires and saddle blankets and other such garbage, and a lacy negligee like a bawdy ghost dripped from a thorn bough and from some lowland grave a rosewood casket unearthed by the deluge floated downstream and spun in an eddy before the current took it on, and in the darker woods beyond the roar of the river was the slow ping and drip of water so that this world seemed cold and cavernous and in unceasing plummet.

Sheriff Elvis Dunne drove the cruiser slowly along the river road, the brake discs steaming as the tires pushed through the ponded rainwater. He was a small man with clean hands. In middle age, his face had acquired the grooved, vaguely scuffed look of old furniture, though his hair had grown to a dark chestnut brown that gave credence to the rumor that he had it dyed. However, he was otherwise known as a man without vanity.

He was fond of antiques, a collector. Those who called on him at home usually found him stowed in a room of urns and carafes, tapestries and gilt mirrors, his hands working linseed oil into the stained wood of a footstool, and though he had a fondness for the aged and dusty, he wasn’t a man opposed to progress.

“In ten years,” he said to his passengers, “I’d like to see all the county paved.”

The two riding beside him were state troopers by the names of Donaldson and Pretshue. Water dripped from the clear plastic rain ponchos they wore. Both men kept still and quiet, giving each other brief sideways glances at the lilting rasp of the sheriff’s voice.

“Ten years,” Elvis said. “There won’t be any gravel roads left around here by then. No more washouts and hang-ups. People will have a lot easier time of it then.”

Donaldson pushed a cigarette between his lips and lit it with the cruiser’s lighter. Beyond the windshield, the world was a dim smear. On the north side of the road were bottoms filled with white cattle, some standing belly-deep in sedge grass. On the south side was the Gasping River.

“That’s all fine and good, Elvis,” Donaldson said. “But what I want to know is when you plan to fix people from winding up drowned in your rivers. Believe this is the third one this year.”

Elvis kept his eyes on the road. The wipers squelched over the dirty windshield. “I’ll guess we’ll fix that long about the time the boys down at Eddyville figure out how to keep their cons from going AWOL,” he said.

Donaldson gnawed the butt of his Winston and chuckled, but Pretshue said nothing.

“There’s not much way to fix folks doing each other in,” said Elvis. “What I’ve found anyway. I talk to a lot of these old timers around here and they say it’s worse now than before, but I don’t believe it. Ask me, they’re all just sorry they can’t get out and do awful like they used to.” He wiped a finger over his teeth, scratched the plaque away with his thumbnail, then wiped his finger against his trouser leg. “They just don’t like being benchwarmers,” he said. “That’s all it is.”

“Old timers,” Donaldson said, slinging water from the brim of his hat. “You’re about to be one yourself aren’t you, Elvis?”

“If I live long enough.”

“Old timers,” repeated Pretshue. “What the fuck do they know?”

Elvis cracked his window and the rain flitted in. “One thing I do know is how much I hate this weather,” he said.

The cruiser topped a rise and Elvis let it coast to the bottom before pulling under a stand of cottonwoods where several other cruisers were parked already. An ambulance idled there also, as well as the county coroner’s burgundy Buick. Beyond the trees, the Gasping rolled by, its waters swollen from the recent rain. Men stood on the shore. Elvis’ deputies, shrinkwrapped in raincoats. At their feet, a body bound with logging chain.

“Reckon that’s our boy wrapped up in those?” Donaldson asked.

“I hope to hell it is,” said Pretshue. “That fucker has been trouble and I hope he’s drowned. That’d solve my headaches.”

All three men exited the cruiser. Elvis went first down the steep bank, followed closely by the two troopers. The deputies nodded to him as he approached, but only gave cold glares to Donaldson and Pretshue.

When Elvis reached the river bank, he squatted beside the body. The fishes and turtles had been at it and some of its fingers were missing and a wet reek like carpet left too long in a cellar hung in the air.

“Whoever did it, Elvis, they weighed him down with this.” The coroner toed a three foot section of railroad track lying in the mud. He was a tall thin man with a dark complexion and under the blank sky he seemed like a streak of ink running out of the clouds. He spoke with a deep wet croak. “It wasn’t enough,” he said. “Two old boys out running trot lines come on him this morning. Just floating. I’d say he’s been under for a day at the most and probably not even that long.” The coroner propped his boot on the section of track and wiped both hands against his trousers and then through his hair. He wore no raincoat. “What I mean is, I’d wager he was put in there last night.”

Elvis nodded and scraped at his chin. “Looks like somebody gave him a swat to the head there,” he said, pointing to the puckered wound on the dead man’s brow. “This your boy, Donaldson?”

The trooper stepped closer and leaned in, stowing his hands on his knees.

“I don’t know. Hard to tell from what the river’s done to him.” Donaldson stood up, running a thumbnail over his belt. “I thought you would know him, Elvis.”

“Me? Why would I know him?”

“Well, this is your county. You run him in when he had the wreck and killed that woman. I thought you’d know him.”

Elvis sighed. He dragged his hat lower on his brow. “That,” he said, “was nine years ago.”

Pretshue pushed his hands into his pockets. The plastic poncho rattled around him, and his nostrils flared as a green tint rose under his cheekbones. “Hell,” he said. “If you don’t know him, then who does?”

Elvis stood up and looked at the covey of deputies. “Where are those old boys at that found him?”

Someone pointed downstream.

Under a red gum stood two men, each dressed in ball caps and shiny rubber hip-waders. They drank coffee from Styrofoam cups. Their johnboat was hitched to a sycamore root jutting from the bank, and they watched it closely as if it were a nervous horse they expected to bolt at any moment.

“He was out there,” one of them said when Elvis and the troopers approached. The man raised his coffee cup and pointed to the river with his pinky, but the world before his finger was unmarkable and without definite origin, an empty spill before windbraided trees, and he might have meant any place in all that wide coursing surge. “We brung him to shore then called you boys down.” He looked past Elvis at the body lying in the sandy mud. “Dead as a drownt cow.”

“Yes.” Elvis nodded. He took a small steno pad and pen from his shirt pocket and began running the pen nervously over the notebook wires. “He is.”

The man who’d spoken snuffled and drew a sleeve under his nose. His friend, features honed like a hatchet blade, put his hands in his pockets and rocked on his boot heels. “You know who it is, don’t you?” he asked.

Elvis flipped the steno pad open, holding the white page under his hat out of the rain. “No. Do you?”

“Course. That’s Paul Duncan. The one stole that car and hit that Cliver lady about ten years back. The same one busted out of Eddyville a few days ago.” The man drained his coffee cup and swallowed. “That’s Loat’s boy.”