Читать книгу East of Acre Lane - Alex Wheatle - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION BY PAUL GILROY

ОглавлениеAlex Wheatle and I belong to the same small and highly exclusive club. Like him, I once livicated a book to the memory of Reggae’s crown prince, Dennis Brown – a philosophical hero and visionary. It is not a spoiler to tell you that his rootical anthem ‘Deliverance Will Come’ is among the tunes that feature in the story you’re holding. That particular Jamaican classic opened the epoch-making 1978 album Visions of Dennis Brown. It matched the honeyed anguish of Dennis’s melodious vocal to Lloyd Park’s rugged bass and some positively rude rockers drumming. ‘Deliverance Will Come’ remains a big tune because it captures the historical texture of the vexed period covered by this rich and rewarding novel. Even now, Dennis’s exquisite projection of the sufferers’ utopian imagining of a world transformed is powerfully evocative. His words offered an invitation to join a collective process of reasoning that promises to bring a better world closer and contribute to repairing all the damage done in this one by the works of Babylon. Alex Wheatle’s novel enacts the same upful possibility.

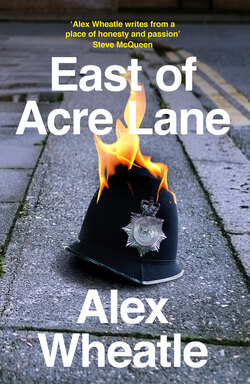

East of Acre Lane is not about music, but reggae music flows through it, supplying the vital fluid to its pressured veins. Wheatle uses that sound and song to open a spot in time and to identify the moral conflicts and boundaries of the community that provided him with this pageant of characters. During this pivotal period, Dub reached its creative peak. Music was still more than merely entertainment. It afforded ethical guidance and delivered precious, useful access to ancestral, I-thiopian truths that could be applied to the dilemmas and conflicts generated in and around black life by exploitation, marginalization and oppression. The social, cultural and moral roles of music became more significant as the bitterness that had built up over the previous decades eventually began to flare. The dance was a place of instruction, of healing, and potentially, of insurgency, constantly surveilled and regulated under the watchful eyes of the police, as corrupt as they were brutal.

This novel’s historical and geographical setting should be carefully specified. It can be defined by the immediate aftermath of the New Cross Massacre, which occurred 18 January 1981 and claimed the lives of thirteen young people. That terrible tragedy had been met with governmental indifference and judicial hostility. The traumatised victims were treated as criminals, and the stories callously spun about them in the press by the police studiously and provocatively ignored the history of racist attacks and fascist organizing in the area.

The New Cross Massacre Action Committee supported the victims and denounced the empty response of the authorities. They called the Black People’s Day of Action on 02 March and galvanized Britain’s black communities into action. They formed a unified political body that carried a welcome glimpse of positive future possibilities. Thousands marched northwards in the rain from New Cross Rd., through an attempted police blockade at Blackfriar’s Bridge, and headed up Fleet Street where they were showered with contempt and hostility delivered from the headquarters of the newspapers that had orchestrated the criminalization of a whole generation.

After that initial fightback, South London’s notorious ‘nigger-hunting’ police were determined to exact symbolic revenge upon the local youth who, we’re told, had been emboldened by the triumphant day of action. To put them back in their proper, lowly place, Brixton police launched their ‘stop-and-search’ response: Operation Swamp 81 on 06 April. Its heavy-handed aggression precipitated unprecedented outbreaks of collective violence that came eventually to express the bleak predicament of all of this country’s young people. The eruptions were certainly the culmination of a longer conflict between the police and the militant layer of rebel youth, an explosive instance of the black communities’ bitter struggles against the habitual racism of Britain’s criminal justice system.

The burning and looting extended from April until July. They spread from Brixton to encompass the whole country, which was changed in profound and lasting ways as a result of what the violence revealed. As we approach the fortieth anniversary of those riots, it is important to reflect upon the meaning, character and importance of them, especially given the current conditions are not always hospitable to historical sensibility. Wheatle’s tale is set in the recent past. His history links with present circumstances, which have in turn been shaped by it. Contemporary conditions are in some ways better and in some ways worse. We look at the present in relation to the past, which is recast here, in the words of Dennis Brown, as ‘the half that has never been told’.

The official statistics say that at that time there was 50 per cent youth unemployment among young black people in Lambeth. However, the nationwide arrest data from 1981 show that participation in the riots was far from narrowly confined to what were then called ‘ethnic minorities’. The Economist trumpeted that the scale of those events conclusively demonstrated the failure of Britain’s welfare-state settlement. In July, the New York Times published a notably more accurate and considered interpretation of the disturbances than any that the British press could muster:

Spreading urban violence erupted in more than a dozen cities and towns across England yesterday and early today as policemen and firemen fought to control thousands of black, white and Asian youths on a spree of rioting, burning and looting. A senior Government official said that the disturbances, which came as the epidemic of violence in the dilapidated inner cities entered its second week, were the most widespread to date. In some cities, he said, “we are facing anarchy.” By 5 A.M., most of the violence had been brought under control, but sirens and burglar alarms could still be heard through the streets of London, and palls of smoke rose from half a dozen districts. From Battersea and Brixton in the south to Stoke Newington in the north, and from Chiswick in the west to Walthamstow in the east, rocks and shattered glass littered at least ten multiracial neighborhoods.

(R. W. Apple, ‘New Riots Sweep England’s Cities; “Anarchy” Feared’, New York Times, 11 July 1981)

Mass antipolice violence clustered around the carnival in Ladbroke Grove had first exploded in 1976. Five years later, because the rioting continued for so long, and could apparently unfold anywhere, the national mood became increasingly anxious and fearful. Perhaps the race war so apocalyptically predicted by the populist Conservative politician Enoch Powell, in his 1968 bid to become party leader, appeared more plausible after the scale of rioting had shifted from smoldering quotidian resentment against police harassment to more spectacular varieties of resistance.

The riots were rooted in young people’s experiences of inequality and injustice. They were also configured by youth’s slowly dawning sense of the chronic character of the crisis that engulfed them and of the unholy forces unleashed by accelerating de-industrialization of urban zones. Once the flames and the adrenaline subsided, the sense of hopelessness was pervasive. Here again, music supplied healing, reparative therapy. There is a balm in Gilead. This was not a crisis of identity but rather the steady birth of a particular dissident culture assembled with love and care from fragments donated by Black Power, Rastafari livity and the combative, insolent resources found in local working-class life.

It is difficult now to judge whether those events should still be considered contemporary. Social life in Britain has evolved. Amplified by the internet, the gaudy dreamscape of consumer culture has discovered new value in iconized and celebrity-faced diversity. Convivial interaction across the axes of class, gender and marginality is often unremarkable. In sharp contrast, the political imagination of the most recent rioters has supposedly contracted to the point that their assaults on power and injustice brought only the transient pleasures of wholesale shopping without money. So we must ask whether changes in the politics of race, and in the way that racism conditions both culture and politics, have been sufficient to draw a line – to create a strong sense of a before and an after. That possibility is pending in this novel.

Remembering this period in the city’s life has become difficult not least because the neoliberal moods that hold sway these days require a disaggregation of the past. It deteriorates into an undifferentiated, abstract sense of history which can be glimpsed intermittently, in fragmentary form, on YouTube, but does not appear to be connected to the world we inhabit. If history reappears at all, it is likely to be no more than an aimless plethora of firmly localized ‘back stories’ that lack an overarching narrative apart from some half-articulated notion of inevitable progress towards a fairer and richer way of life enhanced perhaps by a new generation of technological toys. Those very mechanisms of mass distraction obstruct the insurgent operations of countermemory. This is where the imaginative work accomplished artfully by East of Acre Lane comes in.

It is sometimes easier, more popular and even remunerative for black writers to dwell on the injuries and injustices that result directly from racial downpression than to open up the difficult and painful questions that surround the hurt that downpressed people routinely do to one another. These different dimensions of racialized life in difficult circumstances are knotted together. It takes a special bravery and responsibility imaginatively to enter and explore their entanglement. In his poetic, Fanonian surveys of the conditions that gave rise to bitterness and violence, another Brixtonian, Linton Kwesi Johnson, has described the lateral violence found among racism’s victims as merely the first, transitional phase of their reaction against the institutional power that demeans and confines them. They turn on those they love and vent the effects of racial stress into the vulnerable lives of their nearest and dearest. Wheatle heads straight into the unforgiving territory located beyond the options of protest and affirmation. Armed with an ear for the language of the streets and a refined appreciation of its comic aspects, he mines that unsettling space and has unearthed a gem.