Читать книгу Pointing at the Moon - Alexander Holstein - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

RECENTLY, I have been asked many questions by people wanting to know what Ch'an is. The problem is that describing Ch'an is not an easy task. It is something that can be neither talked about nor expressed in written words; the moment language is used, we are no longer dealing with the true spirit of Ch'an. Ch'an goes beyond all words.

However, Ch'an cannot be left unexpressed. In order to introduce the reader to the world of Ch'an, there is no alternative but to resort to the use of language. That is why there are so many books written on Ch'an.

What is Ch'an? Ch'an is the abbreviated form of the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit term Dhyana (meditation). Better known to the West by the Japanese pronunciation "Zen," it is translated as "quiet contemplation." However, Ch'an has almost nothing to do with the practice of Dhyana.

As stated above, it is rather difficult to describe what Ch'an is through the medium of words. Some people say that Ch'an is mysterious experience, the realm of mystery, or simply mysticism.

If Ch'an is mysterious experience, then Ch'an is the direct realization of the original nature of the self. If it is the realm of mystery, Ch'an is the substance of true emptiness. If it is mysticism, Ch'an is the cornerstone of all doctrines and teachings, the source of all ideas. To define what Ch'an is in this way is admissible on paper, but it is absolutely inadequate as a means of transmitting the Truth.

In fact, Ch'an is neither the experience nor the realm, less still the ism." Ch'an is only Ch'an, neither more nor less. Realizing the true essence of Ch'an, one can attain it in the same manner as one attains the Enlightened mind of Buddhahood. This means the extensive realization of Lord Buddha Sakyamuni, of perfect mind and pure feeling, who, at thirty-five years of age, sitting quietly under a Po-ti tree, realized that the way to release oneself from the chain of rebirth and death lay not in asceticism but in moral purity.

Most people think that Ch'an is something subtle and mysterious, that it is so profound that it cannot be measured and is too high to be reached. These are the feelings of those who observe Ch'an from the outside. But Ch'an is everywhere. It is something that can be found within every one of us. As a religious practice, most certainly, Ch'an is something absolutely personal, wherein for the development of one's own individual consciousness, one is led toward universality.

The first important condition for universality is to organize oneself, summoning up one's full energy and free will. That is why a practitioner of Ch'an, in every waking moment, has to correct his or her own experience, making it bright and free from impurity. Otherwise, a dangerous tendency to take an extra-subjective point of view can be developed. The only way to prevent this is to use the method of self-examination in order to constantly see the real nature of the self. On the other hand, it is not possible to reach Enlightenment through intellectual effort alone. Since it is something that has no face, and no world, Enlightenment does not lend itself to detailed explanations, so people have no way of transmitting or interpreting it. Complete realization (Enlightenment, Awakening) and its testimony can be grasped only intuitively. The Ch'an masters understood wisdom not as rational knowledge but as intuition. For this wisdom, it is very important to reach a point of "absence of thought." The mind should free itself from the influence of the external world, bring itself into sharp focus, and be alert in order to intuit the Truth everywhere, instantly. To this end, special methods have been devised to throw off intellectual work and imagination and allow the pure mind to make its own discovery.

The most commonly used method, especially from the eighth through the eleventh century, has been the "public case" (kung-an in Chinese, koan in Japanese). This method of questioning and eliciting responses may consist of scolding, beating, or constant preoccupation with strange and objectively untenable mind utterances. The task is to wake up, shock, and sensitize a person's mind so as to stimulate him or her to seek the truth on his or her own. This was the first stage, the "hard way" of educating through enigmatic words, gestures, and acts, to make the disciple of a Ch'an master cultivate himself or herself. Later, the questions and answers were set not so much as stumbling blocks for the intellect but as the means or signs of intuition. They were used by the Ch'an masters in order to test or to verify whether their disciples had achieved realization or not. In the modern sense, this could be seen as a kind of examination. The only difference is that its form and content change according to the individual, the time, and the place. There are no uniform answers. Neither is it passed through thinking or rationalization. That is why it is sometimes very difficult to understand the reasoning of the Ch'an sayings.

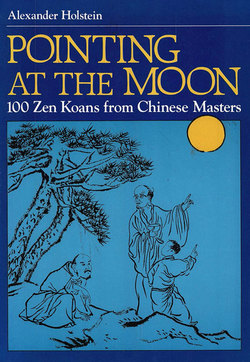

This book comprises one hundred brilliant examples of the Ch'an masters' questions and answers from the following four treatises of the Ch'an tradition: A Selection From the Five Books of the Ch'an Masters' Sayings, The Light of the Ch'an Sayings Recorded in the Year of Developing Virtue (A.D. 1004), The Ch'an Sayings Recorded During the Moonlit Meditation, and An Anthology of Ch'an Sayings, through which, we hope, the reader can find his or her Ch'an mind.