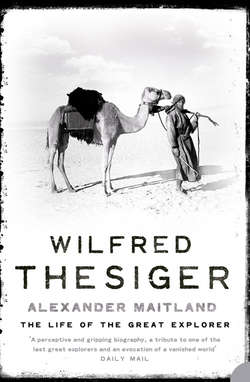

Читать книгу Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of the Great Explorer - Alexander Maitland - Страница 10

FOUR ‘One Handsome Rajah’

ОглавлениеIn the heart of the British Legation’s dusty compound at Addis Ababa, Wilfred Patrick Thesiger was born by the light of oil lamps at 8 p.m. on Friday, 3 June 1910, in a thatched mud hut that served as his parents’ bedroom. The following day his father wrote to Lady Chelmsford, the baby’s grandmother: ‘Everything passed off very well and both are doing splendidly. He weighs 8½lb and stands 1ft 8in [corrected in another letter to 1ft 10in] in his bare feet and his lungs are excellent…He is a splendid little boy and the Abyssinians have already christened him the “tininish Minister” which means the “very small Minister”. We are going to call him Wilfred Patrick but he is always spoken of as Billy. He has a fair amount of hair, is less red than might have been expected and has long fingers.’1

On 12 July Thesiger was christened at Addis Ababa by Pastor Karl Cederquist, a Swedish Lutheran missionary. Count Alexander Hoyos and Frank Champain were named as godfathers; his godmothers were Mrs John Curre and Mrs Miles Backhouse, the wives of two British officials. Captain Thesiger reported proudly: ‘The man Billy [whom he called ‘a jolly little beggar’] grows very fast and puts on half a pound every week with great regularity. I think he is quite a nice looking baby. He has a decided nose and rather a straight upper lip, his eyes seem big for a baby and are wide apart.’2 Frank Champain had accepted his role as the baby’s godfather with reluctance. He would write to Wilfred in 1927: ‘Sorry to have been such a rotten Godfather. I told your Dad I was no good…I can’t be of much use but if I can I am yours to command.’3

Thesiger’s good looks, inherited from his father, were strengthened by his mother’s determined jaw and her direct (some thought intimidating) gaze. As a baby he was active, alert and observant. His adoring parents took photographs of him at frequent intervals from the age of one month until he was nine. They preserved these photographs in an album, the first of four similar albums they compiled, one for each of their sons. Some of the earliest photographs show Billy cradled in his mother’s arms or perched unsteadily on his nurse Susannah’s shoulder, grasping her tightly by her hair. Susannah, a dark-skinned Indian girl, stayed with the Thesigers for three years, working for some of the time alongside an English nurse who proved so incapable and neurotic that Wilfred Gilbert felt obliged to dismiss her. To the devoted, endlessly patient Susannah, little Billy could do no wrong. ‘When my mother remonstrated with her,’ Thesiger wrote, ‘she would answer, “He one handsome Rajah – why for he no do what he want?”’4 Thesiger may have heard his mother tell this story, mimicking Susannah’s broken English.

Though he walked at an unusually early age, Thesiger admitted that he had been slow learning to speak. He said his mother told him that his first words were ‘“Go yay” which meant “Go away” and showed an independent spirit’.5 One day the Thesigers found Billy in Susannah’s hut, lying on the earth floor surrounded by the servants, who bent over him performing a mysterious rite. Susannah reassured the astonished couple: ‘We were just tying for all time to our countries.’6

The child’s birthplace, a circular Abyssinian tukul of mud and wattle with a conical thatched roof, like an East African banda or a South African rondavel, could scarcely have been a more appropriate introduction to the life he was destined to lead. Thesiger realised this, and used to talk about being born in a ‘mud hut’, which implied that the circumstances of his birth were more primitive than they had been in reality. He also liked to stress any extraordinary adventures during childhood which helped to explain his longing for a life of ‘savagery and colour’7 In his early fifties Thesiger confessed that he had probably exaggerated his preferences and dislikes – his resentment, for instance, of cars, aeroplanes and twentieth-century technology foisted on remote societies he called ‘traditional peoples’. He wrote in The Marsh Arabs:

Like many Englishmen of my generation and upbringing I had an instinctive sympathy with the traditional life of others. My childhood was spent in Abyssinia, which at that time was without cars or roads…I loathed cars, aeroplanes, wireless and television, in fact most of our civilisation’s manifestations in the past fifty years, and was always happy, in Iraq or elsewhere, to share a smoke-filled hovel with a shepherd, his family and beasts. In such a household, everything was strange and different, their self-reliance put me at ease, and I was fascinated by the feeling of continuity with the past. I envied them a contentment rare in the world today and a mastery of skills, however simple, that I myself could never hope to attain.8

Thesiger did not experience this sense of easy harmony among remote tribes at Addis Ababa, nor indeed for many years after he first left Abyssinia. Throughout his childhood and his teens, even as a young man in his early twenties, he lived in a European setting, with European values imposed by his family. He had felt instinctively superior by virtue of his background, education and race. Until the 1930s, he admitted, he was ‘an Englishman in Africa, travelling very much as my father would have travelled’.9 He fed and slept apart from the Africans who accompanied him. In 1934 in Abyssinia he read Henri de Monfreid’s book Secrets de la Mer Rouge, and afterwards sailed aboard a dhow from Tajura to Jibuti. Sitting on deck, sharing the crew’s evening meal of rice and fish, Thesiger realised that this was how he wanted to live the rest of his life. During the next fifteen years he accustomed himself to living as his tribal companions lived, in the Sudan, the French Sahara and Arabia. Meanwhile, reflecting on his influential childhood in Abyssinia, he said: ‘When I returned to England [with my family in 1919] I had already witnessed sights such as few people had ever seen.’10

Aged only eight months, early in 1911 Thesiger was taken by his parents on home leave. Carried in a ‘swaying litter between two mules’,11 the baby travelled three hundred miles from Addis Ababa to the railhead at Dire Dawa, and from there by train and steamer to England. A few months later this long journey was repeated in reverse, following the same route Thesiger’s parents had taken in November 1909. ‘The water for his baby food on these treks had to be boiled and then strained through gamgee tissue; his nurse hunted out the tent for camel ticks before he went to bed at night.’ Once, when Thesiger’s nurse had carried him a short distance from camp, they found themselves face to face with a party of half-naked warriors. ‘But she need not have worried, the warriors were just intrigued by a white baby; they had never seen such a sight before.’12

In 1911, to avoid the hot weather, Thesiger and his mother, escorted as far as Jibuti by an official from the Legation, travelled to England ahead of his father, who arrived there on 15 June with members of an Abyssinian mission representing the Emperor at the coronation of King George V. The second of Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen’s sons, Brian Peirson Thesiger, was born at Beachley Rectory in Gloucestershire on 4 October 1911. Wilfred Gilbert had bought the house, with its large overgrown garden overlooking the Severn estuary, to provide his expanding family with a home of their own in England. Billy and Brian became inseparable. Sixteen months older, Billy dominated his younger brother, who seemed content to follow his lead. Those who knew the two elder Thesigers affirmed that this continued for the whole of Brian’s life. Whereas Wilfred Thesiger and his youngest brothers, Dermot Vigors (born in London on 24 March 1914) and Roderic Miles Doughty (born in Addis Ababa on 8 November 1916), had inherited their parents’ looks, Brian bore little obvious resemblance either to the Thesigers or to the Vigors. From his mother’s side no doubt came his reddish fair hair and his freckled, oval face – colouring and features which set him apart from Wilfred, Dermot and Roderic. In his late twenties Brian’s face showed more bone structure, but even then he bore little resemblance to his brothers. Lord Herbert Hervey’s successor as Consul at Addis Ababa, Major Charles H.M. Doughty-Wylie, nicknamed Brian ‘carrot top’ because of his red hair.13 Roderic Thesiger was named after Charles Doughty (who had changed his name to Doughty-Wylie before he married, in 1907, a rich and ‘capable’ widow, Lily Oimara (‘Judith’) Wylie).

Thesiger’s childhood recollections from the age of three or four were clear, lasting and vivid. He remembered his father’s folding camp table with Blackwood’s Magazine, a tobacco tin and a bottle of Rose’s lime juice on it. He remembered, aged three, seeing his father shoot an oryx, the mortally wounded antelope’s headlong rush, and ‘the dust coming up as it crashed’.14 How many animals he saw his father kill for sport we don’t know. The only others he recorded apart from the oryx were two Indian blackbuck, ‘each with a good head’,15 and a tiger his father shot and wounded in the Jaipur forests in 1918 but failed to recover. Such sights as these had thrilled Thesiger as a boy; they fired his passion for hunting African big game, most of which he did in Abyssinia and the Sudan between 1930 and 1939. He continued to hunt after the Second World War in Kurdistan, the marshes of southern Iraq and in Kenya. By the time he arrived in northern Kenya in 1960, however, his passion for hunting was almost exhausted, and he only shot an occasional antelope or zebra for meat.

In 1969 Thesiger told the writer Timothy Green how as children he and Brian sat up at dusk in the Legation garden, waiting to shoot with their airguns a porcupine that had been eating the bulbs of gladioli. ‘Before long Brian, who was only three, pleaded “I think I hear a hyena, I’m frightened, let’s go in.” “Nonsense,” said Wilfred, “you stay here with me.” Finally, long after dark, when the porcupine had not put in an appearance, Wilfred announced, “It’s getting cold. We’ll go in now.”’16 Thesiger’s conversation shows how, aged less than four and a half, he was already taking charge in his own small world. He went on doing so all his life. A born gang leader, Thesiger dominated his brothers, just as, as a traveller, he would dominate his followers.

He was aware of this tendency, and in later years he strove to play it down. In My Kenya Days, he stated: ‘Looking back over my life I have never wanted a master and servant relationship with my retainers.’17 A key to this is his instinctive use of the term ‘retainers’: literally ‘dependants’, or ‘followers of some person of rank or position’. Throughout his life he surrounded himself with often much younger men, or boys, who served him and gave him the companionship he desired. Many of them, initially, owed Thesiger their liberty, or favours in exchange for financial assistance he gave them or their families. These favours affected their relationship with him, in which the distinction between servant and comrade was frequently blurred.

As a child Thesiger had ruled over his younger brothers, even using them as punchbags after he learnt to box. The ‘fagging’ system at Eton encouraged his thuggish behaviour, which was tolerated only by friends who realised that he had a gentler side, which he kept hidden for fear of diluting his macho image. It was characteristic of him, from his mid-twenties onward, that he would choose ‘retainers’ younger than himself, over whom he exerted an authority reinforced by the difference between their ages, as well as by his dominating personality and his position or status – for example, as an Assistant District Commissioner in the Sudan, and in Syria an army major ranked as second-in-command of the Druze Legion. In contrast, Thesiger’s relationships with his older followers were seldom as close or as meaningful. The same applied to his young companions in Arabia and Iraq after they became middle-aged and, in due course, elderly men. Thesiger reflected: ‘I don’t know why it was. They were just different. We had travelled together in the desert and shared the hardships and danger of that life. When I saw them again, thirty years later, they lived in houses with radios and instead of riding camels they drove about in cars. The youngsters I remembered had grey beards. They seemed pleased to see me again, and I was pleased to see them; but something had gone…the feeling of intimacy, and a sense of the hardships that once bound us together.’18

At the Legation, Thesiger’s parents encouraged the children to play with pet animals, including a tame antelope, two dogs and a ‘toto’ monkey his mother named Moses. Kathleen wrote: ‘Altho’ we kept [Moses] chained to his box at times, we very often let him go and then he would rush away and climb to the nearest tree top, only to jump unexpectedly from a high branch on to my shoulder with unerring aim. Every official in the Legation loved my Moses and he was so small that they could carry him about in their pockets. He was accorded the freedom of the drawing room [in the new Legation] and I must confess that I still have many books in torn bindings [which] tell the tale.’19

Thesiger remembered Moses and the tiny antelope wistfully, with an amused affection. He commented in My Kenya Days: ‘My father kept no dogs in the Legation,’20 but this was a lapse of memory. Later he remembered: ‘Our first dog in Addis Ababa was called Jock. The next dog had to be got rid of because Hugh Dodds [one of Wilfred Gilbert’s Consuls] thought it was dangerous. This was about 1916…As a child, I was afraid of nothing but spiders…When we were at The Milebrook, the first dog I owned was a golden cocker spaniel, and it died of distemper. I had only had the dog for about a year.’21

In The Life of My Choice Thesiger pictured his childhood at Addis Ababa against a background of Abyssinia in turmoil. This was the chaotic legacy of the Emperor Menelik’s paralysing illness and his heir Lij Yasu’s blood-lust, incompetence and apostasy of Islam. The turbulent decade from 1910 to 1919 gave the early years of Thesiger’s life story romance and power, and enhanced the significance of his childhood as a crucial influence upon ‘everything that followed’.22 As a small boy he was no doubt aware of events he described seventy years later in The Life of My Choice, however remote and incomprehensible they must have appeared at the time. In reality his life at Addis Ababa had little to do with the Legation’s surroundings – except for its landscapes, including the hills (Entoto, Wochercher and Fantali) and the plain where Billy and Brian rode their ponies and went on camping trips every year with their parents. On these memorable outings Mary Buckle, a children’s nurse from Abingdon in Oxfordshire, accompanied the family. Mary, known to everyone as ‘Minna’, had been engaged in 1911 to look after Brian. Thesiger wrote in 1987: ‘She was eighteen and had never been out of England, yet she unhesitatingly set off for a remote and savage country in Africa. She gave us unfailing devotion and became an essential part of our family.’23 Just as he idealised his father and mother, Thesiger idealised Minna, whom he admired as brave, selfless and indispensable. He wrote affectionately in The Life of My Choice: ‘Now, after more than seventy years, she is still my cherished friend and confidante, the one person left with shared memories of those far-off days.’24 This statement was literally true. Thesiger, a confirmed bachelor, respected strong-willed, practical women, mother figures whose common sense and devotion tempered their undisputed authority. Thesiger’s occasional travelling companion and close friend Lady Egremont later remembered visiting Minna with him at Witney in Oxfordshire. She watched as he smoothed his hair and straightened his tie, ‘like a twelve-year-old schoolboy on his best behaviour’,25 as they waited for Minna to open her front door.

Every morning after breakfast, Billy and Brian would find their ponies saddled and waiting with Habta Wold, the Legation syce (the servant who looked after the horses), who usually accompanied them. The boys had learnt to ride by the time they were four. They rode most mornings, and sometimes again in the afternoon. On a steep hillside five hundred feet above the Legation there was a grotto cut into the rock. From there Billy and Brian had tremendous views, to the north over Salale province and the Blue Nile gorges, southward to the far-off Arussi mountains. There, one day, Billy would follow in his father’s footsteps and hunt the mountain nyala, a majestic antelope with lyre-shaped horns. Aged four, he had been photographed with a fine nyala trophy head.

After their morning ride Billy and Brian did schoolwork, which consisted of reading, writing and arithmetic; sometimes they drilled with the Legation’s guard. After lunch they rode again or tried to shoot birds in the garden with their ‘Daisy’ airguns. Thesiger wrote: ‘Had it not been for the First World War I might have been sent to school in England, separated indefinitely from my parents, as was the fate of so many English children whose fathers served in India or elsewhere in the East. I must have had some lessons at the Legation, though I have no recollection of them, for I learnt to read and write.’26 The idea of very small children being sent away to school did not appeal to Thesiger, who spoke out strongly against it; but he approved of preparatory boarding schools and, of course, segregated public schools, for older children.

Because he was so obviously fond of children – and, indeed, very good with little girls and boys – he was often asked why he had never married and had a family of his own. In his autobiography, the phrase The Life of My Choice, selected for the book’s title, occurs in a paragraph where Thesiger affirms his attitudes to marriage and other ‘commonly accepted pleasures of life’. He wrote: ‘I have never set much store by them. I hardly care what I eat, provided it suffices, and I care not at all for wine or spirits. When I was fourteen someone gave me a glass of beer, and I thought it so unpleasant I have never touched beer again. As for cigarettes, I dislike even being in a room where people are smoking. Sex has been of no great consequence to me, and the celibacy of desert life left me untroubled. Marriage would certainly have been a crippling handicap. I have therefore been able to lead the life of my choice with no sense of deprivation.’27 He later added: ‘The Life of My Choice was the right title for the book I wrote about myself. It gave you everything. I had lived as I wanted, gone where I wanted, when I wanted. I travelled among peoples that interested me. My companions were those individuals I wanted to have with me.’28

Thesiger’s impossible dream had been to preserve the near-idyllic life he had known as a boy in Abyssinia. He viewed change dismally, as a threat to the tribal peoples he admired, and to himself as a self-confessed traditionalist and romantic who ‘cherished the past, felt out of step with the present and dreaded the future’.29 Such a reactionary outlook had been doomed from the start, and Thesiger knew it. And, of course, without a sword of Damocles hanging over it, the life he dreamt of would have been spared the impending threat of corrosive change, perhaps of annihilation – a fate later exemplified by the destruction of the marshes in southern Iraq. He took an aggressive pride in being the ‘last’ in a long line of overland explorers and travellers, a refugee from the Victorians’ Golden Age. In a romantic fit of self-indulgent melancholy, he yearned for an irretrievable past summed up by the robber-poet François Villon’s poignant query: ‘Où sont les neiges d’antan?’30 – ‘Where are the snows of yesteryear?’ Ironically, from Thesiger’s bachelor-explorer viewpoint, this quotation, taken from ‘Le Grand Testament: Ballade des Dames du Temps Jadis’, lamented not the vanishing wilderness or its tribes, but the sensual, white-bodied women Villon had slept with during his dissipated youth, in fifteenth-century Paris.

Thesiger’s father and mother were supremely important figures during his early childhood, and took pride of place in his idealised (and romanticised) memories of those halcyon days. He wrote of his father: ‘Inevitably at Addis Ababa he was busy for most of the day, writing his despatches, interviewing people or visiting his colleagues in the other Legations…it was perhaps in the camp where we went each year from the Legation for an eagerly awaited ten days that I remember him most vividly. I can picture him now, a tall lean figure in a helmet, smoking his pipe as he watched the horses being saddled or inspected them while they were being fed; I can see him cleaning his rifle in the verandah of his tent, or sitting chatting with my mother by the fire in the evening.’31

The camp’s setting was remote, perfect: ‘an enchanted spot, tucked away in the Entoto hills. A stream tumbled down the cliff opposite our tents, then flowed away through a jumble of rocks among a grove of trees. Here were all sorts of birds: top-heavy hornbills, touracos with crimson wings, brilliant bee-eaters, sunbirds, paradise flycatchers, hoopoes, golden weaver birds and many others. My father knew them all and taught me their names. Vultures nested in the cliffs and circled in slow spirals above the camp. I used to watch them through his field glasses, and the baboons that processed along the cliff tops, the babies clinging to their mothers’ backs. At night we sometimes heard their frenzied barking when a leopard disturbed them. Several times I went up the valley with my father in the evening and sat with him behind a rock, hoping he would get a shot at the leopard. I remember once a large white-tailed mongoose scuttled past within a few feet of us.’32

Thesiger’s lifelong interest in ornithology dated from visits to this ‘enchanted’ enclave among the hills. As a boy he continued to shoot birds, and went on shooting them for sport and scientific study; but from then on he began to see and to recognise birds not as mere targets, but as living things that were fascinating as well as beautiful. The juvenile diaries he kept in Wales and Scotland between 1922 and 1933 contain detailed observations on local birdlife. During his Danakil expedition in 1933-34, Thesiger shot and preserved no fewer than 872 bird specimens, comprising 192 species, and three sub-species new to science which were named after him.

The chubby, smiling baby grew up as an extremely good-looking if rather sombre child who, his father noted, seemed very shy in the company of adults other than his parents.33 As a boy of six he had thick brown hair tinted with his mother’s auburn, and large, expressive eyes. His mouth, like Kathleen’s, was wide, with small, slightly uneven teeth shielded by a long upper lip (like Wilfred Gilbert’s) which were hardly seen except when he was speaking energetically or laughing. In those days his nose was long and quite straight. Only after being broken three times did it acquire the misshapen, craggy character that led his oldest friend, John Verney, to describe him as ‘a splendid pinnacle knocked off the top of a Dolomite’34 Although they went about protected from the hot sun by large sola topees, Billy and Brian must have had permanent tans which no doubt set them apart as creatures secretly to be envied by the pale-skinned little boys at their English preparatory school. The healthy outdoor life they led made the brothers fit and strong, with muscular arms and legs, and without an ounce of spare flesh on their lean brown bodies.

The Emperor designate, Lij Yasu, was one of three Abyssinian boys who, then and later, played roles of varying significance in Thesiger’s life. The other two were Asfa Wossen, the baby son of Ras Tafari, Abyssinia’s Regent after 1916 and the country’s future Emperor; and a nameless child, nine or ten years old, who had fought with Tafari’s army at Sagale. Abyssinia’s political chaos worsened from 1911 when Lij Yasu, aided by Menelik’s commander-in-chief Fitaurari Habta Giorgis, seized the palace and took control of the country. Lij Yasu was never crowned. This had been impossible during his grandfather’s lifetime, and after Menelik’s death in December 1913 a prophecy stating that if he were crowned he would die may have discouraged him. Lij Yasu meanwhile embraced Islam, and lived for long periods with the warlike Danakil (or Afar) tribes, hunting and raiding villages for provisions. An arrogant, cruel youth, he took pleasure in watching executions and floggings. To satisfy his blood-lust he massacred Shanqalla Negroes on the Abyssinia–Sudan border, and slaughtered three hundred Danakil, including women and children, in Captain Thesiger’s opinion ‘simply because he liked the sight of blood’.35 Besides these atrocities Lij Yasu was rumoured to have himself killed and castrated a page at Menelik’s palace; and according to one of his officers, when a girl refused to have sex with him, Lij Yasu sliced off her breasts after watching her being gang-raped by his soldiers.

The Life of My Choice – described by Thesiger as ‘a fragment’ of autobiography36 – tends to bury its subject under an avalanche of impersonal details. Though absorbing, these details are far more comprehensive than the often meagre infill of Thesiger’s life history requires. As well as exploiting its historical context to the full, Thesiger used the wealth of factual information about his life to produce a ‘treasure galleon’ of a book, written ‘with much distinction and honesty’,37 yet offering few noteworthy revelations about its author. Nowhere in The Life of My Choice is this more apparent than in the opening chapters, describing Thesiger’s background and his early upbringing in Abyssinia and England.

In 1913–14 Thesiger’s father trekked from Addis Ababa to Nairobi to discuss with the Governor of British East Africa (later Kenya) border issues created by Abyssinian slavers, ivory raiders and the large populations of Boran and Galla tribesmen who migrated to East Africa from Abyssinia after Menelik had conquered their territory. Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger noted in 1911 that the Abyssinians had occupied the Turkana territory in British East Africa and Karamoja in Uganda, although the Abyssinian frontier established in 1907 lay to the north of these territories. In his teens Thesiger was fascinated by books such as Major H. Rayne’s The Ivory Raiders (a fourteenth-birthday present) and Henry Darley’s Slaves and Ivory, which provided an exciting background to his father’s mission. As a boy of three and a half, however, he remembered only vaguely the journey with his parents and Brian to the Awash station, the next railhead that replaced Dire Dawa until the Chemin de Fer Franco-Ethiopien’s line from Jibuti had progressed as far as Addis Ababa, its ultimate destination. Almost fifty years later he wrote in Arabian Sands that his attraction to ‘the deserts of the East’ might lie ‘in vague recollections of camel herds at waterholes; in the smell of dust and of acacias under a hot sun; in the chorus of hyenas and jackals in the darkness round the camp fire’. Such ‘dim memories’38 as these derived from this and other journeys with his parents. They suggest that even as a child Thesiger was unusually observant and receptive to the sights, scents and sounds of the African bush and of the Abyssinian highlands where he lived for almost nine incomparably happy years. In 1914 Kathleen, who was pregnant once again, returned to England, and by the time Wilfred Gilbert joined her there at the end of March, the Thesigers’ third son, Dermot Vigors, had been born.

On his way to Nairobi Captain Thesiger wrote to Billy and Brian in London from camps at Laisamis and the Uaso Nyiro river, places which the younger Wilfred would often visit during his travels in Kenya. He treasured his father’s letters, written in pencil on coarse grey paper, illustrated with lively drawings of giraffes, lion and warthogs. Wilfred Gilbert may have got the idea of illustrating his stories with thumbnail sketches of big game from Sir Percy Fitzpatrick’s South African classic Jock of the Bushveld. First published in 1907, the book was illustrated with hundreds of drawings, and many half-tone plates, by Edmund Caldwell. The earliest impressions of Jock had Caldwell’s uncorrected sketch of a dung beetle pushing a tiny ball of dung with its front, instead of its back, legs. Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen each owned a first edition of the book, and Thesiger remembered his father reading from it in the evenings, sitting on the entrance steps of the Legation. Later, Wilfred Gilbert gave Billy his copy, which the little boy inscribed proudly in pencil: ‘W P Thesiger – from Daddy Adiss-Ababa – Abysinia’. (In 1995 Thesiger sold his mother’s copy, inscribed by her, rebound, with more of his child’s pencilling erased from it, but still perfectly legible.)

Thesiger often emphasised how his father never talked down to him, but instead gave him ‘a happy sense of comradeship’ and ‘shared adventure’.39 His father’s letter from Laisamis, he said, ‘could have been written to a boy of seven; I was only half that age’.40 This was a harmless exaggeration, like Thesiger’s suggestion that he alone had been the recipient of the letter; whereas it was addressed, using the children’s euphonic pet names, to both Billy and Brian. The Laisamis letter began:

My dear Umsie [Billy] and Wowwow [Brian]

Daddy has been having a very good time hunting…daddy shot [a rhino] in the shoulder & he turned round & wanted to charge but we shot him again and soon he was quite deaded…41

As she read Wilfred Gilbert’s letter aloud, Kathleen must have pictured her husband in his khaki shirt and riding breeches, smoking his pipe in the shade of his fly-tent or under a shady tree; writing with meticulous care on official paper ruffled now and then by the wind; sketching wild animals he described to bring his words alive. His account of shooting a female rhino clearly illustrates the dramatic change in our attitude to wildlife since the days when big game hunting was viewed uncritically (indeed, was strongly justified and admired) as sport. Nor was the episode by any means untypical of hunting adventures at that period. ‘Last night,’ he wrote, ‘two of our soldiers were out at night & they were attacked by an old mummy rhino which had a baby one with her and they had to shoot but they had not many cartridges & did not kill her & then they had to whistle for help & we all took our guns & ran out & daddy shot her and she fell but got up again & we all fired again until she was deaded & then we chased the baby one in the moonlight & tried to catch him but could not as he ran too fast.’42

As a small boy Thesiger was thrilled by stories such as these. As he grew older he memorised tales of lion hunts and of fighting between warlike tribes told by his father’s Consuls. Arnold Wienholt Hodson, a Consul in south-west Abyssinia, hunted big game including elephant, buffalo and lion. Aged six or seven, Thesiger pored over Hodson’s photographs of game he had shot, and listened spellbound to his stories. Later he read Hodson’s books Where Lion Reign, published in 1927, and Seven Years in Southern Abyssinia (1928). Introducing Where Lion Reign, Hodson wrote: ‘In this wild and little-known terrain which it was my mission to explore, lion were plentiful enough to gladden the heart not only of any big game hunter, but of all those whom the call of adventure urges to seek out primitive Nature in her home among the savage and remote places of the earth.’43

By then Wilfred Thesiger was at school in England. As a teenager yearning to return to Abyssinia, his birthplace and his home, he drank in like a potent elixir Hodson’s words, which defined precisely the life he aspired to, the life he was determined one day to achieve.