Читать книгу 1 Recce - Alexander Strachan - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

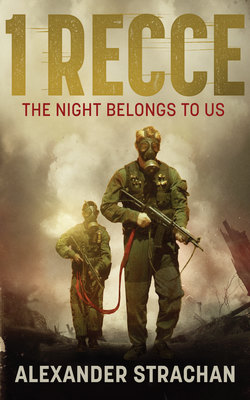

‘The night belongs to us’

ОглавлениеMoving stealthily, Hannes Venter’s group stalk the Shatotwa 1 base. In the bright moonlight, their surroundings are clearly visible. Their weapons are cocked, the safety catches set on ‘fire’. As they come closer, they see the grass roofs of the huts gleaming in the moonlight. It is ominously quiet; not even the sound of a dog barking. It worries them – the thought that no dogs are barking. Surely every camp has a dog or two; why aren’t the dogs picking up their scent?

With everything shrouded in total silence, the group anxiously lie waiting for first light, that brief grey period between daybreak and sunrise. It is a pleasant winter night, though, as expected, somewhat cool. The closer it gets to morning, the more the temperature drops. But when the Recces took off their backpacks, their backs were dripping with sweat. In the chilly breeze they are now starting to feel cold.

In front of them, the sleeping Swapo base is waking up. The silence is suddenly broken by sounds of motion, men coughing and grunting as they get up and stretch their bodies after the night’s sleep. Muted muttering and dry coughs can be heard from all sides. The guards at the entrance to the base – barely 40 m from the attack force – light cigarettes and start chatting unsuspectingly. But there is always the risk that something may alert them to the presence of the Recces on their front stoep.

At a distance of some 300 m, Charl Naudé’s group lie waiting. Positioned about 20 m from the Shatotwa 2 base, they are waiting for Hannes to ‘spring’ the attack on Shatotwa 1 at first light. The moment Hannes and his team start firing, Charl’s group will attack. According to their information, there are about 120 soldiers at each of the two Swapo bases.

As they wait for Hannes to launch the attack, someone steps out of a hut right in front them. It is a Swapo fighter without his gun, heading towards the concealed Recces. He is walking straight towards Lt. LC Odendal, who has dug himself in next to a metre-high bush. The rest of the team shift slightly and then they are again stock-still. But every AK-47 is now firmly trained on the approaching man. Adrenaline pumps through the operators’ veins. They hold their breath, their hearts in their mouths.

The man stops right in front of LC. He is evidently still half asleep, for the next moment he urinates on top of LC without spotting him. This is too much for LC, and he shoots the man dead there and then.

The moment the shot rings out, everyone simultaneously opens fire on the base with AK-47s and RPG-7s. At the same time all hell breaks loose 300 m away, where Hannes’s team bombard Shatotwa 1 with AK-47s, RPG-7s and mortars.

Their first target is the guards at the control point and sentry post. They were either killed instantly or have fled, as they stop returning fire after a few moments. Some of the Recces’ RPG-7 rockets hit the huts. At least three right ahead of them catch fire, creating a wall of flames 15 m in front of the attack force that brightly illuminates the Recces’ own positions. Above their heads, tracers and ordinary bullets pierce the air with sharp banging sounds.

Shots are now also being fired from the main base in the direction of Charl’s group. This fire is not really noteworthy since the whole camp has clearly been caught asleep. At Shatotwa 1, Hannes’s force now all rise from their positions and start advancing. Immediately they come under fire from light machine guns (LMGs). The LMG positions are in the north-western section of the base and fairly close to the Recces.

Hannes’s force continue their attack with fire-and-movement tactics. They do not run as usual, however, but execute the attack at a rapid walking pace. Walk and shoot, walk and shoot without stopping so that the group maintains its momentum. RPG-7 rockets and mortar bombs are exploding everywhere in the base and ripping it apart. The Recces shoot with lots of tracer bullets in their magazines, which causes the dry grass to catch fire. Eventually the whole camp is ablaze. In the glow of the flames they see the Swapos running and zigzagging to dodge the bullets.

The base has been caught so off guard that most of the Swapo soldiers’ weapons are still in their huts. The Recces mow down a great many of them with PKM machine guns, AK-47s and RPG-7s, with the mortars delivering overhead fire from a short distance. In the early-morning serenity of the bush, the roar of the explosions and machine-gun salvoes is deafening.

Tracer bullets whizz through the air trailing bright streaks of light a metre above the ground, and people wilt before the onslaught like blades of grass. The Recces continue to advance.

Perhaps the battle lasted only some minutes. Afterwards, it was impossible to recall the duration. To some Recces it might have felt like hours, but after a few minutes they had already moved through the objective.

Then the deathly quiet that is so characteristic of firefights set in. Their ears buzzing, the Recces did not even know whether or not Swapo kept returning fire, they were too focused on their own task. In the din of battle, they would not have been able to hear the enemy fire anyway. But now, in the silence, for the first time they become aware of the groans of the injured Swapo fighters.

* * *

As in the case of the above attack, the men of 1 Recce often used the cover of night to maintain the element of surprise against a numerically superior force. (The full story of the attack on the Shatotwa bases is told in chapter 12.) Accordingly, their motto was ‘The night belongs to 1.1 Commando’. For the Recces, the night was the ideal time to conduct their operations – it rendered them invisible to the enemy and to other prying eyes that might betray their presence. During daytime they preferred to lie motionless in their hide. From that concealed position they would scan the environs with an eagle eye to gather information about what was happening around them.

Inconspicuousness was the watchword, and the team would not betray their presence through sounds, smoke, smells or tracks. Maintaining the element of surprise was crucial. The operators employed advanced tactics such as anti-tracking to avoid detection – they erased their own tracks behind them so that the enemy would not even know they had entered the area.

The Recces conducted prior reconnaissance operations to identify their target, and in some cases higher authority (e.g. Military Intelligence) initiated the deployment. Depending on its sensitivity, the operation would be authorised by the Chief of the Defence Force or by the minister of defence – in some cases by the state president himself.

The Recce team’s leaders would plan an operation in the strictest secrecy with as few people as possible involved. At unit level, the Recce commander was responsible for the planning. Only after the plan had been rehearsed in the finest detail over weeks or months would the Recce teams be deployed on the mission under their unit commander.

Inside enemy territory, the team would lie up in one place during the day and then, just after last light (the period between sunset and darkness), move out of their hide under the cover of night. The objective was now to infiltrate the target they would attack at an appropriate time (midnight, for instance). Their withdrawal plan would have been worked out to the last detail, with all possibilities having been considered: on foot, from the air, or by sea.

Depending on the circumstances, they would be picked up by a helicopter after the operation. If not, the team would first put considerable distance between themselves and the target before again concealing themselves in a daytime hide before first light (between dawn and sunrise). There they would wait for darkness before moving to a predetermined landing zone where the chopper would pick them up. With each operation, the target, the terrain and enemy movements would inevitably determine what procedure would be followed.

When 1 Recce operators were deployed in foreign countries, they knew full well that their presence there was unwanted and illegal, and that they would be hunted down mercilessly if they were discovered. To avoid this possibility, they were preferably deployed clandestinely in smaller teams. But they could also be deployed as part of a larger attack force such as Unita, which had lots of firepower. Larger groups were more defiant and the task would be executed aggressively, after which the force would return to safety. In such cases (where there was a strong offensive capability) it would indeed be possible to move during the day with scouts.

Night work and nightime operations were second nature to the members of 1 Recce, as they were schooled in this from the outset. Their training during the rehearsal phase’s night-work programme would be done at exactly the same time as that scheduled for the execution of the operation. If the target had to be attacked at 02:00, for example, the rehearsal would also take place at 02:00 so that the operators could become accustomed to the conditions under which they were going to work.

Almost all operations were conducted at night, preferably during dark-moon periods. In fact, the night and foul weather conditions were the 1 Recce operator’s greatest friend and ally. Years of employment under such conditions made him a master of night warfare.

A well-trained soldier moves more easily at night with the stars as direction indicators. It is cooler, too, and there are fewer eyes that may spot you; you can relax more and focus better. Aids such as night-vision goggles could be used to improve visibility in the dark. But at the most basic level the Recce operator ‘saw’ with his ears and nose at night and let himself be guided by these senses.

The person who looks at light from the darkness at night has an advantage – his eyes have adjusted to the dark, and the target is clearly visible. On the other hand, it is much harder to look from light at an object in the dark.

At night you can also get much closer to the target without being spotted; this is vital in the case of reconnaissance work and intelligence gathering. In daytime, by contrast, the playing fields are level: both sides can see and react equally well, all the more so if the enemy is entrenched in a base or building.

The Recces regularly used ‘black is beautiful’ camouflage cream to mask their identities, but the disguise was only effective from a distance; at close quarters, the enemy would recognise their true features through the camouflage cream. The blackening of their skins did give them an advantage when they and the enemy ran into each other unexpectedly in the bush. The momentary confusion on the part of the enemy made them hesitate before firing. The South African team could then swiftly jump into action with small arms and RPG-7s.

In the same way that the Recce operator regarded the night as his confidant, he treasured the African bush as a precious ally. While outsiders experienced the bush with its wild animals, reptiles and impenetrability as hostile, the Recces saw it as a friendly and supportive environment on which they depended for their survival. They existed in total harmony with the bush and used its waterholes, shadows, shelter, food and vegetation to survive from day to day in a war situation.

Hence the young Recce learnt from very early on not to rebel against the bush or try to fight it. The bush was neutral, not hostile towards you, and your relationship with it was determined exclusively by your own attitude. It was only once you had learnt to notice the cobwebs and umbrella thorns from your subconscious that you knew you had finally merged with the bush – from now on you were at one with it. Now every twig became a toothbrush, every berry a sweet to suck on, every seemingly dry riverbed an inexhaustible water source.

By now you knew that the hot sun on your cheek could enable you to determine direction and stay on course without consulting your compass; also that the direction in which an anthill sloped at the top showed you where north is.

The sweat on your body had dried and you now smelt like the veld, like the dust, the trees, the leaves and the creepers. Once you experienced this level of comfort you did not survive in the bush, you thrived in it, as a seasoned Recce operator has rightly remarked.

At this level of situational awareness, every spoor sent out a signal, every sound helped to fill in the bigger picture. Your actions were subconsciously calculated, your feet moved effortlessly over the dry branches without making one snap. You slipped soundlessly through the shadows and melted into the dark patches. You smelt the grass, you smelt the dew, the soil was soft and accommodating. Your ears were constantly cocked and you heard the crickets, and then, when they abruptly fell silent, you knew …

1 Recce was primarily an airborne unit, which meant that parachute capabilities played an integral role. The three daggers on the 1 Recce shoulder flash signified land, sea and air, while the compass rose indicated that operations could be conducted in all directions, by day and by night (hence the black-and-white shoulder flash). Prospective operators were exposed to all the techniques during their training.

For a typical airborne attack, the Recces would be transported to the target area in a camouflaged C-130/C-160 aircraft. It flies at a low altitude, barely above the treeline, to evade detection by enemy radar. In the dark it is invisible to the naked eye. The heavily armed 1 Recce operators on board have been rubbed in with ‘black is beautiful’; their static-line parachutes are attached to the overhead cable, and the chutes and equipment have been checked. Now just a few red lights are on inside the plane. Only when it is very close to the target will it bounce up to the jump altitude of about 183 m above ground level, when the dispatchers open the jump doors. The wind immediately rushes noisily into the cargo hold and tears at clothes and equipment.

Then the aircraft bounces up to the jump altitude. The sudden upward thrust presses the jumpers floorwards until the aircraft stabilises at the new altitude. The red light above the open door goes on, and the dispatchers call out: ‘Stand in the door!’ As soon as the green light switches on, the Recces jump out in quick succession. Their parachutes deploy, and suddenly they hang in absolute silence. In the available moonlight they see the other parachutes around them and the aircraft flying off.

The low jump altitude means that the earth approaches very rapidly. Then they land one after the other on the unmarked drop zone. Here and there branches creak as some of the jumpers fall through trees. Now it is completely quiet, and the group is ready for action.

The attack force would lie motionless for a short while to listen for any enemy movement. Then they swiftly roll up the parachutes and move to a predetermined rendezvous point, where the chutes are usually first cut up and then concealed. Thereafter, still under the cover of night, they move stealthily towards the target. On completion of the night attack, the team move to a pick-up point from where, if possible, they will be extracted by a chopper before first light. The longer they remain on the ground, the higher the risk becomes.

In the case of reconnaissance and smaller sabotage teams they could reach the target by alternative means, namely high-altitude infiltration methods. The C-130/C-160 aircraft would then fly the same route and at the same altitude as civilian aircraft (10 668 m) to avoid attracting attention and to evade radar detection. They would usually also fly at the same times as the commercial airlines’ flights.

In such cases there would only be a very small group of Recce operators in the large aircraft. They wear specially designed jump helmets and masks that are connected to an oxygen system. The operators are camouflaged with ‘black is beautiful’, their backpacks heavily laden with rations, water, explosives and other items for the mission deep behind enemy lines that may last a few weeks.

Ten minutes before jump time the parachutes and equipment are checked by the dispatchers. All lights have been switched off; only a few red lights are on. Three minutes before jump time the flight engineer opens the loading ramp at the rear of the aircraft. The wind noise is so loud that everyone now communicates only by means of hand signals. One minute before jump time the jumpers activate their oxygen bottles and disconnect them from the aircraft’s system.

The team move towards the ramp and prepare for the HAHO (high altitude high opening) jump. It is bitterly cold. At 10 668 m the temperature is around -54 degrees Celsius, depending on the atmospheric conditions. All the operators can see is the black void in which not even fires on the ground are visible. Despite the freezing cold, the men are dripping with sweat under their specially designed suits because of all of the adrenaline.

Then it is P-hour, the moment that the first jumper has to exit the aircraft. The green light flashes and the Recces dive out of the plane into the dark unknown. After about three seconds the parachutes are opened, and the team form up in a stack to stay together in the air. It is quiet, each jumper hears only the sound of his chute’s stabilisers flapping in the wind. The other chutes are faintly visible. The long descent to the landing zone has started.

It is always unbearably cold during a HAHO jump; hands and feet feel as if they have turned into blocks of ice. The team leader navigates his team with his GPS towards a landing zone that may be as far as 20 km from the jump area.

At an altitude of about 3 660 m above the ground the men uncouple their oxygen masks on the one side and lift the freefall goggles as they try to see the ground. The terrain gradually becomes more visible. When the ground finally comes into view, they look for a suitable landing zone. It is hard to accurately determine the wind direction, but this aspect is vital in ensuring a safe landing with the heavily laden backpacks and weapons.

Just before landing the jumpers turn their parachutes against the wind in an attempt to make a soft landing. Trees, stones, rocks and other objects pose the biggest danger. The team members also have to land as close to each other as possible. Suddenly the earth is approaching fast, and it feels as if it is rushing up to meet the jumper. As he hits the ground, his cold-numbed feet and legs do not really feel the impact of the landing.

After a brief wait they roll up the parachutes and carry them some distance away to be stashed, usually inside an old aardvark hole. If the chutes are not going to be recovered, they first cut them up quickly. In the dark the team now move to a predesignated lying-up position from where they will observe the previous night’s drop zone throughout the day. In particular, they watch out for movements that may indicate whether the enemy has caught wind of their presence.

In the case of a reconnaissance operation, one of the two operators would remain behind under cover fairly close to the target. The other, dressed in very light clothing and armed with only a silenced pistol, would approach the target painstakingly slowly to conduct the close-in recce. This is an extremely dangerous phase of the operation that is essential for gathering detailed information. On completion of the recce, the team would move stealthily under the cover of night to a predesignated landing zone.

According to schedule they switch on the VHF ground-to-air radio, although no talking will be done. At a given moment, the team leader flashes a code with his infrared torch in the dark in the direction of the approaching helicopter. As soon as the pilot identifies the team’s code, he would say the word ‘visual’ only once over the radio and then land. With the team on board, the helicopter would fly back in the dark at treetop level to the 1 Recce base somewhere in the operational area.

Intense tension usually reigned in the last few hours before an operation began. But as soon as the Recce operator landed in enemy territory, whether by parachute or helicopter, a great calmness set in. The moment his feet touched the ground, he got an almost euphoric feeling of being in total control.

Another thing no Recce operator will ever forget is the absolute stillness in the bush moments before the start of an attack. It was as if time stood still and the birds, the animals and even the plants were holding their breath in anticipation of something terrible that was about to happen. This stillness is reminiscent of the silence that hung around you as soon as your parachute unfolded when you were jumping in an operation.

Likewise, the smell of helicopter fuel during startup stays in your memory. The men who worked on submarines, again, will never forget the distinctive submarine smell. It is a fusty mixture of odours – diesel, engine, grease, sweat and kitchen – that would seep into your clothes and skin if you had spent long periods on board.

Even years after he had left the unit the Recce operator would still remain conditioned not to talk loudly when entering a bushy area. And it disturbs him when others do so – to him, a forest or thicket will always be the place where hand signals replace voices, and where you only communicate in whispers in extreme cases.

The Recces were highly adaptable to working in a variety of conditions, and were also employed in pseudo operations where they took on the guise of the enemy. They would wear the enemy’s clothing and carry their weapons, and talk, walk, eat and think like the enemy. In the process they would become the enemy, physically as well as psychologically.

These operations were more difficult to control, and sometimes friendly forces would exchange fire because one had mistaken the other for the enemy. As a preventative measure, the entire area in which they were due to operate would usually be ‘frozen’, which meant that no one else was allowed to enter it.

A typical pseudo operation could for instance be conducted by two (or more) men. The team usually consisted of a South African leader and a former enemy member who had ‘turned’ and now operated with him against his erstwhile comrades. During infiltration, this team member would walk in front of the team leader so that he could immediately strike up a conversation if they bumped into unexpected elements.

The technique of ‘turning’ an enemy combatant originated with the Selous Scouts in the then Rhodesia. The Rhodesians might have adopted it from the British who had used and developed this concept against the Mau Mau in Kenya. One method was to tell captured soldiers after interrogation that their comrades would be informed that they had cooperated with their captors and disclosed details of secret structures. The fear of reprisal was generally a sufficient deterrent to prevent them from rejoining their own forces.

Access routes to the target would be reconnoitred as well as escape routes, the best direction of attack, and the time and distance between the target and the drop-off point or lying-up position, where the operators lay concealed during the day. They would always make sure that alternative lying-up positions were available.

These positions were usually in thick bush, but not on prominent high ground or terrain where the enemy might deploy their own observation posts. Operators had to be able to camouflage themselves there while at the same time having a good view of their access route. Once they had identified a suitable spot, the team would first move past it and then return in a roundabout way to occupy the lying-up position.

Great emphasis was placed on anti-tracking, and once the position had been occupied, there would be no further movement. Everyone lay in silence, listening and observing. This phase would be nerve-racking for two-men reconnaissance teams in particular. Good camouflage and absolute silence were cardinal. An operator would lie on his back, wearing combat gear (chest rig and magazines) and with his firearm at the ready against his body. Once he was in a prone position, he would cover his body with branches, grass, leaves and soil to camouflage himself.

Members of the local population who came to gather firewood or just wandered around were always a big problem. Also goats, with their odd habit of staring unceasingly at something strange in the veld, could draw unwanted attention to the group. Then there was the ever-present danger of dogs that came sniffing about – for this eventuality, a .22 or .32 silenced pistol was kept on hand. If a dog smelt or discovered them it would be shot soundlessly, after which the operator would cautiously rise from his position and drag the dead animal to a concealed position under bushes. No other movement was allowed in the hide – no one was allowed to eat, make coffee or even take a toilet break. Everyone would lie motionless, waiting for the night to finally welcome them like an old friend.

In the early 1980s, the South African battlefront started changing; the focus now began to fall not only on the bush but also on urban environments, and urban warfare came into play. Inspired by the Israeli Special Forces’ hostage-rescue raid on Entebbe Airport in Uganda on 4 July 1976, a number of operators from 1 Recce were sent to Israel to do a course in urban warfare. The Recces subsequently designed their own courses that were applicable to the conditions under which they worked.

In the same way that the operators used the bush to their advantage, they now exploited the built-up area’s shadows, noises, dress codes and traffic to blend in with the urban environment.

They wore civilian clothes in enemy cities, with firearms concealed under their jackets. They would walk in loose groups, those who were able to would converse with the people in the local language, and they would avoid suspicious movements as well as any military formation. Depending on the operation, the Recce operator might pass himself off as a tourist in search of pubs or nightclubs.

The target in the city was studied in detail beforehand to acquaint the team with the layout, traffic patterns and hiding places. Sometimes tramps and their habits were studied, and the Recces would then dress and act like them without attracting attention.

As the cities were always deep inside enemy territory, the enemy had a false sense of confidence that they were secure and out of reach of action against them. When the first shots rang out and the stun grenades went off, it invariably came as a total surprise.

The objective of the operations was to raid enemy headquarters and hiding places and collect documentation and other sources of information. Thereafter demolition charges were laid in the target to destroy it completely. After the raid the Recces would immediately disappear again in the city among the buildings, dens and streets to make their way to a predetermined point to be extracted.

Successful execution of such an operation depended on a proper prior urban recce. The close-in recce was usually carried out by one man (sometimes two), who would walk or drive past the target once or twice. In the process, an abundance of information would be gathered: what do the doors look like, and in which direction do they open; is there burglar proofing, and how strong is it; are there pipes indicating the presence of gas in the kitchen; and what do the locks on the doors look like?

All these details and many more were thoroughly memorised in passing, and photos were taken with hidden cameras. If vehicles were used, EMLC1 (highly qualified engineers at the Special Forces headquarters) would equip the vehicle with all-round invisible cameras that could be controlled from the inside.

These operations were extremely specialised and operators were sometimes transported to the target by sea, or otherwise inserted by helicopter at a particular point from where they continued on foot. Sometimes Puma helicopters would fly them in with motorcycles on board and drop them about 50 km, depending on the situation, outside the city. The teams would then approach the target on their powerful 500 cc Honda off-road motorcycles. While the operators raided the target, their comrades would keep the motorcycles running.

On completion of the operation, they would pick up the attackers and drive to a predetermined landing zone to be extracted. A typical raid on a target would sometimes last only a minute or two. The attack was always a total surprise, and the team would already be out of the area before the enemy was able to react.

1 Recce was very well trained in urban warfare; in fact, it was one of their major fields of specialisation. Sometimes agents were used to supply vehicles in the target city. In such cases the teams were launched from the sea and met the agents on the beach. They would then drive to the target and return in the same vehicles to the beach to be extracted.

With urban operations, the team used urban noises to their advantage. Heavy traffic or a plane passing overhead would mask the shots of especially silenced MP-5s and AK-47s (submachine guns equipped with silencers). At times the operators would wear specially designed jackets in which weapons and equipment could be concealed. The jackets blended in with the clothing worn by the local population, but had Kevlar reinforcement that protected them against shrapnel and small-arms fire.

Like phantoms, 1 Recce sneaked around in enemy cities in the midnight hours, slipping from one dark patch to another. In emergencies, they would vanish without trace in the underground city structure. Just as they used the African bush to render themselves invisible, the city and all its structures were now employed for the same purpose.

Sea and river operations were also conducted during dark-moon and half- and quarter-moon periods. The operators would approach ports and coastal targets unobtrusively in special boats with low profiles and muffled engines, and infiltrate them. The many dark places in the harbour area were ideal hiding places.

River banks, too, had patches of shadow in which the target could be approached unnoticed. The team would pull camouflage nets over the kayaks and disappear with the silent-rowing technique – with the water as their most valuable anti-tracking ally.

They chose their landing sites very carefully to avoid leaving suspicious tracks on the bank, and wore shoes that were equipped with the enemy’s sole pattern. At times they would wear ‘olifantvoete’ (elephant feet) – a kind of sock made out of canvas – over their boots to hide their tracks. The sole part of the elephant feet contained sponge that left a fuzzy, indistinct oval-shaped track. Some of the men would use their elephant feet as pillows at night. At times the operators would get out of the boats with bare feet, especially if there were many fishermen in the area. Once they reached a safe and suitable spot, they would again put on the boots with the sole pattern of the enemy.

Cooperation between the different Recce units was paramount for them to be operationally effective. Equally vital was the role of the support personnel. Without the right equipment, transport, medical assistance, logistical support and financial peace of mind, the Recce could not focus properly on his mission.

It was also important that his household would keep functioning smoothly in his absence. In this regard, the role of the wives should never be underestimated. They made sure that school attendance, the upbringing of the children and daily maintenance continued, so that the operator could eventually return to a safe and orderly haven. In the success of 1 Recce, the role of the support component was just as integral as that of the operational component.