Читать книгу Stuart: A Life Backwards - Alexander Masters, Alexander Masters - Страница 16

7

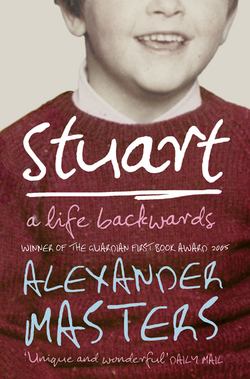

Оглавление‘Stop asking why, Alexander. I don’t know why. I was so off-key, half the time me mind had a head of its own.’ … Psycho! Aged 29

Lion Yard Car Park is a boat of a place. Its cargo hold, nine concrete storeys of smog and tyre burns, is topped by the glass-covered, centrally heated magistrates’ court – the galley, so to speak. The prow of the boat – an eighth of a mile further south, under the Holiday Inn – thrusts towards the university museums of geology and anthropology.

Stuart aged 29 fetched up in this car park after leaving his mother’s pub, meeting Asterix and Scouser Tom, being kicked out of Smudger’s flat and messing up his chances at Jimmy’s and the day centre. He’d been told that ten to fifteen people ‘skippered’ there every night, but wherever he looked he couldn’t find a single one of them. He took his blankets and rags and walked up the circular staircase to the top storey, just under the magistrates’ court, where the pigeons sleep. It took him four days to find the place for people.

Between the magistrates’ court end and the Holiday Inn end of the building are ramps and an aerial walkway, plus a mezzanine basement dug, it seems, into pure concrete. HUMANS NOT ALLOWED indicates an accompanying sign. Another notice reads TO LEVELS A-B-C-D. A little stick man with a ping-pong head marches behind the letters in an encouraging manner, guiding you along a narrow pavement. Grey drops of chewing gum splatter the way, congesting towards a stair door and lift door at the other end. Then Ping-Pong Head pops up again, on a sign hurrying back towards TOILETS. The pillars supporting the ceiling here (we are now under the Holiday Inn) are stencilled with the letter A. IS THIS [A]RT MUMMY? someone has scrawled around one.

By the lift other signs fight for attention. A bewildering list of charges. More funny round-headed stick figures explaining how to stand in a lift. ‘Get into your car or get a move on,’ they appear to say. ‘Stop being such an uncertain quantity.’ A dulled brass honorarium:

To Commemorate the Opening

of the

Lion Yard Car Park Extension

by

The Right Worshipful the Mayor

COUNCILLOR DR GEORGE REID

on

Friday 10 August 1990

Dr Reid, the main university force in our campaign to release Ruth and John: a fine humanitarian, conservative to the ends of his toes (which have gout).

The lift is boarded up. Recently, a student leant against these doors, they opened accidentally and he plunged into the dark down the shaft.

‘PLEASE BE AWARE,’ declares a bill on the door by the stairs, ‘if approached in this car park by someone claiming to need money for petrol or to replace a broken car key please do not give them any money and immediately contact a member of staff at the exit.’

On the other side of the door is the concrete staircase: cinder grey, regular. The banister is red. The smell is dust and disinfectant. Go down two flights. The walls still show the grain of the plywood moulds that once held them when they were poured. If you peer hard through the dark perspex window in the door of this floor – Level B – you can often spot something interesting. Couples kissing passionately in the front seats, couples in the back seats, couples shouting. Depth, in this building, quickly gives a conviction of privacy. Down two more flights and Level C begins to show the strain. The walls are laterally cracked, like an exposed vein of a leaf. Occasionally, the smell loses its warm chemical hint and a waft of urine insinuates itself instead. There are still currents of air.

Down the final two staircases, forty feet under ground, to the lowest subterranean floor. You could take off all your clothes and do handstands down here and you’d be safe any time between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m.

The cleaners have been at this piece of graffiti with their scrubbing brushes many times. Six inches to the right, beneath a picture of a falling bomb, some more:

Above you, the noises could be of people just leaving the staircase at the top; or, equally, stomping across the floor directly above. Sound is impossible to place.

Push through this door, out of the stairwell into Level D, and you will see in front of you 15,000 square feet of car park that is completely empty.

This is where the homeless sleep.

‘’Ere, Jonny, stop pissing on that bloke, he’s trying to snooze.’

‘Can I have another sarnie, pleaaase? I’ve only ’ad three …’

‘Coffee with five sugars, love, ta.’

‘Jonny! Get over here and tell Linda …’

This is where the homeless sleep.

‘Aww, that’s not fair. Penny’s had six. And she’s nicked a burger and chips from that geezer outside Gardenia. Gooo on, jus’ one more …’

‘Is that five? You sure? Put another one in, just in case, pet.’

‘JONNY! He don’t want ketchup poured over him neither! He’s not a frigging hot dog! Come here, it’s important, tell Linda about Psycho. Honest, Linda, not joking, he’s a nutter – he’s taking over Level D. A danger to everyone. Giving us a bad name. Like, we don’t even dare go down to Level D no more. You don’t know him? Where have you been the last five months? JONNY!’

Linda was one of the two members of the Cambridge Homeless Outreach Team in those days. Her job was to walk round the city streets in the evenings talking to anyone who looked homeless: i.e. anyone selling the Big Issue or three months away from a bath or stationed in public spaces at lower than a standing position. On Tuesdays and Thursdays she ran the soup kitchen in the market square. This service is gone now, but in the late 1990s it was not only a charitable provider of food and hot drinks to rough sleepers, it was the best way to learn street gossip.

That evening, after the soup kitchen was locked away, Linda met up with her work colleague, Denis Hayes, an ex-film cameraman, and went to seek out Psycho.

For outreach workers, the best way down to Level D is by the car ramps, because it brings each floor gradually into view – allows them to assess the situation slowly and not to pounce in on it through small yellow stairway doors at one end.

‘I always think if I wanted to do a film again, the scene that night would be the opening shot,’ remembers Denis. ‘I’ll never forget that image. It was, like, coooold. Me and Linda go right down until we get to the last bit, Level D, and that would be how I’d start. Coming down the ramp from Level C above, panning slowly across this eerie, vast space. Empty car park. Left to right: not a car, not a car, not a car, nothing, nothing, and then … Psycho!

‘What he reminded me of was an IRA hunger striker. Skeletal, in his cell, all his things around him. He was like that man in Birdie, crouched on the end of his bed. Nobody could make him up to look how he did at that moment. Angry as hell. Hated me. Hated Linda. Hated everything from the fucking dust upwards.’

Psycho!