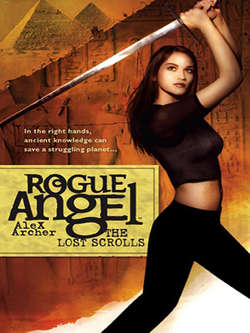

Читать книгу The Lost Scrolls - Alex Archer - Страница 10

6

Оглавление“We’re still waiting,” the fresh-faced Mormon guy said. Although his hair didn’t seem to be receding he managed to show a lot of forehead in the late-morning sunlight. His forehead bulged, somehow.

“For what?” Jadzia asked.

Seagulls wheeled over the Bay of Naples in the bright blue morning sky, complaining of fate. The Mediterranean wind stirred the scrubby pines dotted across the hillside and rattled dust and small porous pebbles against larger rocks and randomly rearranged them in clumps at the bases of the wiry plants. The square smelled of dust and ancient dressed stone and not-so-ancient hot asphalt from the parking lot. Annja felt the weight of time and mortality as she and Jadzia walked with their attentive guides through the ruins of Herculaneum.

Which was a familiar and pleasant feeling for the archaeologist.

The two women were being escorted through a ghost town of pallid stone by several researchers from Brigham Young University and a few employees of the small Herculaneum museum, which, like the site as a whole, was closed to the public at the moment. Annja and Jadzia were getting a personal tour as a professional courtesy.

The researchers seemed excited to meet Annja, a genuine television celebrity, and one from their field—one moreover who might somehow be able to bring the manna of airtime or even coveted television-network dollars to their project. But Jadzia they actually seemed to regard with awe. It was as if a rising baseball superstar were visiting another team’s locker room.

“For the permission by the Italian government,” said Pellegrino. In his early thirties, he was the oldest of the museum crew. He was short and wiry, if a bit bandy-legged. He wore a horizontally striped red-and-blue jersey over shorts. “Further excavation has been held up until the ministry decides whether to give priority to a conservation strategy first.”

“Or until the Americans come up with a bigger bribe,” said Tancredo, a tall young man with a shock of straw blond hair, blue eyes and a Lombard accent.

The volcano-doomed Roman village perched on the warty flank of the mountain that killed it, alongside the modern village of Ercole. This part of the Bay of Naples was postcard-pretty, and seemingly placid despite the volcano’s vast gray dome hulking overhead. But it sported a history almost as long and dense as the land Annja and Jadzia had just left on the other side of the Mediterranean.

“There are legitimate issues at stake!” yelped Tammaro, the third and youngest of the museum crew, who was very short indeed and looked as if he hadn’t shaved in three days. The locals had all been speaking Italian. Now Tammaro, stung by the blond northerner’s suggestion, bubbled into expostulating in the local dialect, quite different from standard Italian. Annja could barely follow.

The Mormon, whose name was Tom Ross, shrugged. He spoke in English. Still, from his body language Annja guessed he had followed the Italian conversation about as far as she had. He had told the visitors he had done his mission in Italy before returning to Brigham Young University, where he was a graduate student.

“A few of us keep on keeping on here,” he said, causing Annja to wonder if this cheerful straight-arrow had any inkling of the phrase’s origin in the drug-happy sixties. “The ministry’s been promising to get us word ‘any time now’ since about February.” BYU, it seemed, wasn’t wasting any full professors on a prospect as tenuous as an Italian ministry doing its job.

Pellegrino scowled and said a word Annja was unfamiliar with. She guessed it was a curse of some sort. Her guess seemed confirmed when Jadzia burst into loud high-pitched giggles. Tammaro hunched his head between his shoulders like a startled turtle and scowled ferociously, an effect somewhat spoiled by the fact that he also turned beet-red.

They walked through a broad courtyard or smallish plaza between the stone faces of excavated buildings, some two stories tall. A palm tree waved badly weathered fronds, half of them dead and brown, in the insistent breeze. The empty doorways and windows looked like openings into skulls, and the sense of desolation was palpable despite the fact they walked through what amounted to a very vital modern city. Maybe it was the sudden and horrid fashion in which so many lives had been snuffed at once by one of Mother Nature’s better-known disasters.

Or perhaps it was the brooding presence of the mountain itself, the two-humped saddle shape, taller Vesuvius separated from ancient Somma by the Valley of the Giant. The old killer lay dormant now, although it had smoldered some a few decades ago.

Annja had studied enough geology to know that a sleeping volcano could wake quickly. It had been realized in her own lifetime that extinction wasn’t necessarily forever, where volcanoes were concerned. And over four hundred thousand people lay in harm’s immediate way if Vesuvius should suddenly take a mind to take up his bad old ways.

“What about equipment to read the scrolls?” Jadzia asked, yanking Annja somewhat guiltily back to the subject pressingly at hand. Merely our own survival, she reflected glumly. “I understood you were going to obtain the equipment to read the carbonized scrolls from the Villa of the Papyri.”

“You mean the machines necessary to perform multispectral imaging and CT scans?” Tancredo asked. “Sorry. Hasn’t happened yet.”

Tom shrugged. “We have an American patron bankrolling much of this operation,” he said. “He’s real generous. But his generosity sort of hits Pause when it comes to shelling out millions of dollars for an undertaking that might take years before it can actually get started. If ever.”

Annja’s lips peeled back from her teeth in a grimace. She could feel Jadzia approaching a boil. But neither said anything.

“But it is a most important question,” Tammaro said, back to speaking intelligible Italian again, “whether to concentrate our efforts on preserving the ancient treasures of Herculaneum and Lucius Piso’s villa, or exploit them for the curiosity and profit of soulless—”

“Oh, put a sock in it, do,” Tancredo said in startling English. “It’s all about the bribes our wealthy patron can be held up for, and the whole bloody world knows it!’

Pellegrino showed a wavery smile to Annja and Jadzia. “Welcome to Italy,” he said.

“WAIT,” Annja said, as the taxi rattled down a fairly rural road carved into the cold lava skirts of Vesuvius, where the picturesque gnarled evergreens and palms of the southeastern, seaward side of the mountain gave slow way to stands of alders and birch trees. Their driver, a stout, sweating man with a mustache and a touring cap, had informed them before lapsing into silence that they must detour to avoid some kind of traffic lockup on the main road that ran along the curve of the bay. “You’re telling me if I don’t believe aliens are visiting the Earth in flying saucers then I’m buying into a conspiracy theory?”