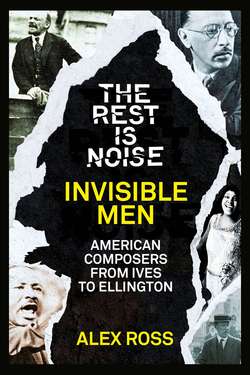

Читать книгу The Rest Is Noise Series: Invisible Men: American Composers from Ives to Ellington - Alex Ross - Страница 6

Оглавление4 INVISIBLE MEN

American Composers from Ives to Ellington

To understand the cultural unease that gripped composers in the Roaring Twenties, one need only read the work of Carl Van Vechten, the American critic, novelist, and social gadfly who, in the 1920s, more or less defected from classical music to jazz and blues. The writer started out as a second-string music critic at the New York Times, dutifully chronicling the city’s concert life in the years before the First World War. During an extended stay in Paris, he warmed to the European moderns and witnessed the riot of the Rite in the company of Gertrude Stein. By the end of the war, though, Van Vechten was getting his kicks chiefly from popular music, and in a 1917 essay he predicted that Irving Berlin and other Tin Pan Alley songwriters would be considered “the true grandfathers of the Great American Composer of the year 2001.” Finally, he pledged his allegiance to African-American culture, writing off concert music as a spent force. In the controversial 1926 novel Nigger Heaven, he observed that black artists were in complete possession of the “primitive birthright ... that all the civilized races were struggling to get back to—this fact explained the art of a Picasso or a Stravinsky.”

The writings of Van Vechten, Gilbert Seldes, and other rebellious young American intellectuals of the twenties show a paradigm shift under way. They depict popular artists not as entertainers but as major artists, modernists from the social margins. In the twenties, for the first time in history, classical composers lacked assurance that they were the sole guardians of the grail of progress. Other innovators and progenitors were emerging. They were American. They often lacked the polish of a conservatory education. And, increasingly, they were black.

One nineteenth-century composer saw this change coming, or at least sensed it. In 1892, the Czech master Antonín Dvořák, whose feeling for his native culture had inspired the young Janáček, went to New York to teach at the newly instituted National Conservatory. A man of rural peasant origins, Dvořák had few prejudices about the social background or skin color of prospective talent. In Manhattan he befriended the young black singer and composer Harry T. Burleigh, who introduced him to the African-American spirituals. Dvořák decided that this music held the key to America’s musical future. He began plotting a new symphonic work that would draw on African-American and Native American material: the mighty Ninth Symphony, subtitled “From the New World.” With the help of a ghostwriter, Dvořák also aired his views in public, in an article titled “Real Value of Negro Melodies,” which appeared in the New York Herald on May 21, 1893:

I am now satisfied that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called the negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States ... All of the great musicians have borrowed from the songs of the common people. Beethoven’s most charming scherzo is based upon what might now be considered a skillfully handled negro melody ... In the negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music. They are pathetic, tender, passionate, melancholy, solemn, religious, bold, merry, gay or what you will. It is music that suits itself to any mood or any purpose. There is nothing in the whole range of composition that cannot be supplied with themes from this source.

At a time when lynching was a social sport in the South, and in a year when excursion trains brought ten thousand people to Paris, Texas, so that they could watch a black man being paraded through town, tortured, and burned at the stake, Dvořák’s embrace of African-American spirituals was a notable gesture. The visiting celebrity didn’t just urge white composers to make use of black material; he promoted blacks themselves as composers. Most provocative of all was his imputation of a “Negro” strain in Beethoven—a heresy against the Aryan philosophies that were gaining ground in Europe.

Black music is so intertwined with the wider history of American music that the story of the one is to a great extent the story of the other. Everything runs along the color line, as W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk. Still, it’s worth asking why the music of 10 percent of the population should have had such influence.

In 1939, a Harvard undergraduate named Leonard Bernstein tried to give an answer, in a paper titled “The Absorption of Race Elements into American Music.” Great music in the European tradition, young Bernstein declared, had grown organically from national sources, both in a “material” sense (folk tunes serving as sources for composition) and in a “spiritual” sense (folkish music speaking for the ethos of a place). Bernstein’s two-tiered conception, which acknowledges in equal mea sure music’s autonomy and its social function, makes a good stab at explaining why black music conquered the more open-minded precincts of white America. First, it made a phenomenal sound. The characteristic devices of African-American musicking—the bending and breaking of diatonic scales, the distortion of instrumental timbre, the layering of rhythms, the blurring of the distinction between verbal and nonverbal sound—opened new dimensions in musical space, a realm beyond the written notes. Second, black music compelled attention as a document of spiritual crisis and renewal. It memorialized the wound at the heart of the national experience—the crime of slavery—and it transcended that suffering with acts of individual self-expression and collective affirmation. Thus, black music fulfilled Bernstein’s demand for a “common American musical material.”

What Dvořák did not foresee, and what even the cooler-than-thou Bernstein had trouble grasping, was that the “great and noble school of music” would consist not of classical compositions but of ragtime, jazz, blues, swing, R & B, rock ’n’ roll, funk, soul, hip-hop, and whatever’s next. Many pioneers of black music might have had major classical careers if the stage door of Carnegie Hall had been open to them, but, with few exceptions, it was not. As the scholar Paul Lopes writes, “The limited resources and opportunities for black artists to perform and create cultivated music for either black or white audiences ... forced them into a more immediate relationship with the American vernacular.” Soon, jazz had its own canon of masters, its own dialectic of establishment and avant-garde: Armstrong the originator, Ellington the classicist, Charlie Parker the revolution-ary, and so on. A young Mahler of Harlem had little to gain by going downtown.

Separateness became a source of power; there were other ways to get the message out, other lines of transmission. Black musicians were quick to appropriate technologies that classical music adopted only fitfully. The protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s epochal novel Invisible Man sits in his basement with his record player, listening to “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.” He says, “Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of being invisible.” The invisible man broadcasts on the “lower frequencies” to which society has consigned him. Incidentally, Ellison once thought of becoming a composer. He took a few lessons from Wallingford Riegger, an early American admirer of Schoenberg. Then, like so many others, he stopped.

To tell the story of American composition in the early twentieth century is to circle around an absent center. The great African-American orchestral works that Dvořák prophesied are mostly absent, their promise transmuted into jazz. Nonetheless, the landscape teems with interesting life. White composers faced another, far milder kind of prejudice; their very existence was deemed inessential by the Beethoven-besotted concertgoers of the urban centers. They tried many routes around the intractable fact of audience apathy, embracing radical dissonance (Charles Ives, Edgard Varèse, Carl Ruggles), radical simplicity (Virgil Thomson), a black-and-white, classical-popular fusion (George Gershwin). For the most part, the identity of the American composer was a kind of non identity, an ethnicity of solitude.

Aaron Copland, whose story will be told in later chapters, once pointed out that the job of being an American artist often consists simply in making art possible—which is to say, visible. Every generation has to do the work all over again. Composers perennially lack state support; they lack a broad audience; they lack a centuries-old tradition. For some, this isolation is debilitating, but for others it is liberating; the absence of tradition means freedom from tradition. One way or another, all American composers are invisible men.

Will Marion Cook

The early history of African-American composition, at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, is full of sorrowful tales. Scott Joplin, the composer of “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer,” spent his last years in a futile effort to stage his opera Treemonisha, which vibrantly blended bel canto melody and rag rhythm. Syphilis invaded Joplin’s brain, and he died insane in 1917. Harry Lawrence Freeman, the found er of the Negro Grand Opera Company in Harlem, wrote two Wagnerian tetralogies with black characters, only one part of which was ever staged. Saddest of all, perhaps, was the case of Maurice Arnold Strothotte, whom Dvořák singled out as “the most promising and gifted” of his American pupils. Arnold’s American Plantation Dances was played at a National Conservatory concert in 1894 to much applause. The conductor-scholar Maurice Peress has shown that Dvořák’s familiar Humoresque borrowed from an episode in Arnold’s work. The conservatory concert was, unfortunately, the high-water mark of the young man’s career. He continued writing music—an opera titled The Merry Benedicts, music for silent films, an American Rhapsody, a Symphony in F Minor—but performances were few. Instead, he made a living conducting operetta and teaching violin. Like the hero of James Weldon Johnson’s Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, he apparently stopped identifying as black, living out his final years in the heavily German neighborhood of Yorkville. Oblivion engulfed him all the same.

Other stories had happier endings. The little-known life of the violinist, composer, conductor, and teacher Will Marion Cook serves as a useful case study in the development of African-American music from 1900 to 1930. If this charismatic, obstinate personality ultimately failed in his quest to conquer the classical realm, he did experience moments of triumph, and blazed a separate trail for many black artists who followed him. Among other things, he forms a direct link between Dvořák and Duke Ellington.

Cook’s biography, sketchily documented, has been pieced together by the scholar Marva Griffin Carter. Born in 1869, Cook grew up in Washington, D.C., the son of middle-class parents. When his father died, he went to live with his grandparents in Chattanooga, where his arrogance created the sorts of disciplinary problems that are often noted in youngsters of unusual talent. He used to go to the top of Lookout Mountain, outside Chattanooga, to plot his future fame. In his unpublished autobiography, he wrote: “I would ... remain there till late at night, planning my whole life, how I would study, become a great musician, and do something about race prejudice ... Somehow I felt that such music might be the lever by which my people could raise their status. All my life I’ve dreamed dreams, but never more wonderful or more grandiose dreams than those inspired by Lookout Mountain.”

Cook was then accepted into Oberlin, one of very few American colleges where black students could enroll alongside whites. A professor noticed his skill as a violinist and advised him to study with Joseph Joachim, who headed the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin. With some assistance from the slave-turned-orator Frederick Douglass, who belonged to Mrs. Cook’s social circle, the boy gained admittance to Joachim’s academy.

The Kaiser’s Berlin proved surprisingly welcoming. According to the autobiography, titled Hell of a Life, Joachim took the young African-American under his wing, expressing a liking for his passionate playing and his untamed personality. “You are a stranger in a strange land,” the violinist supposedly said. “We are going to become friends. Come to my house for lunch Sunday.” At Joachim’s gatherings Cook could have met or glimpsed many of the leading personalities of German music, including Hans von Bülow and the young Richard Strauss. In the winter of 1889, none other than Johannes Brahms came to the Hochschule to celebrate Joachim’s fiftieth anniversary as a performer. In all, Cook seems to have enjoyed his time in Germany; the sight of a black violinist was apparently too exotic to arouse racial fears.

Compare the experiences of W. E. B. Du Bois, who began studying economics and history in Berlin just as Cook left. According to David Levering Lewis’s biography, Du Bois “felt exceptionally free” during his Berlin sojourn—“more liberated ... than he would ever feel again.” On a train ride to Lübeck, Du Bois sang Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy”—“All men will be brothers”—and dreamed of a better world. The young philosopher also became enamored of the Wagner operas, gaining from them an appreciation of how art could inflame national and racial spirit. In his story “Of the Coming of John,” which appeared in The Souls of Black Folk, a Southern youth named John Jones attends a performance of Lohengrin and feels in it the contours of a better life: “A deep longing swelled in all his heart to rise with that clear music out of the dirt and dust of that low life that held him prisoned and befouled. If he could only live up in the free air where birds sang and setting suns had no touch of blood!” Then—here Du Bois reveals his “double-consciousness,” his awareness of how even the most “cultured” black man is perceived—an usher taps John on the shoulder and asks him to leave.

That tap on the shoulder, metaphorical or not, Will Marion Cook came to know well when he returned to America. He tried to make his name as a violinist, advertising himself improbably as a “musical phenomenon performing some of the masterpieces upon his violin with one hand.” Making little headway, he then formed the William Marion Cook Orchestra, with Frederick Douglass as honorary president. At around the same time, Cook wrote, or began writing, an opera based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Most significantly, in 1893, he went to Chicago to participate in the World’s Columbian Exposition, a momentous event at which America declared its new status as a world power. In an effort to counteract the stereo types of black savagery that figured in some of the fair’s displays—crowds flocked to watch and hear the African drummers of Dahomey Village—Douglass organized a Colored People’s Day, which aimed to affirm the nobility of the black American experience. Newspapers mocked Douglass by speculating that watermelons would be sold in bulk.

Colored People’s Day was to have featured excerpts from Cook’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but the singer Sissieretta Jones failed to receive the travel advance that she needed to make the trip, and the performance was canceled. Yet the exposition wasn’t a total waste for Cook. He obtained a letter of introduction to Dvořák, who evidently invited him to study at the National Conservatory. ( Jeannette Thurber, the found er of the conservatory, had a policy of admitting Negro students free of charge.) There is little record of what Cook did during his first years in New York, but circumstantial evidence suggests that racism put a quick end to his dreams. One anecdote is cited in Duke Ellington’s memoir, Music Is My Mistress. Cook makes his Carnegie Hall debut, and a critic hails him as “the world’s greatest Negro violinist.” Cook barges in on the critic and smashes his violin on the man’s desk. “I am not the world’s greatest Negro violinist,” he shouts. “I am the greatest violinist in the world!” Marva Griffin Carter finds no evidence that such an incident took place, but yelling matches probably ensued as the temperamental Cook made the rounds of the concert halls.

Barred from the classical world, Cook got work where he could find it. In 1898 he collaborated with the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar on a musical revue titled Clorindy; or, The Origin of the Cakewalk, which opened on Broadway with an all-black cast. This was, at first glance, yet another self-denigrating minstrel show full of talk of “coons” and “darkeys.” But, as Carter points out, the lyrics often have a hidden sting, making “confrontational jabs” at white listeners. The hit number “Darktown Is Out To night” delivers a prophecy of the coming sovereignty of black music:

For the time

Comin’ mighty soon,

When the best,

Like the rest

Gwine a-be singin’ coon.

When Cook’s mother came to the show, she was distressed to see his Berlin education going to this end. A Negro composer should write just like a white man, she told him. Yet the composer could look back on Clorindy and its successor, In Dahomey, as examples of a black composer finally finding his own voice. “On Emancipation Day,” In Dahomey’s big number, repeats the prophecy of “Darktown” in even starker terms:

All you white folks clear de way,

Brass ban’ playin’ sev’ral tunes

Darkies eyes look jes’ lak moons . . .

When dey hear dem ragtime tunes

White fo’ks try to pass fo’ coons

On Emancipation day.

The first chords of the overture, which recur at the beginning of “On Emancipation Day,” echo the opening of the Largo of Dvořák’s New World Symphony.

Cook’s musicals, sophisticated in technique and assertive in tone, anticipated the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance, which came into its own around 1925. Since the beginning of the century, W. E. B. Du Bois had been calling for a “Talented Tenth” of black intellectuals and artists to lead the masses to a better place in society. The upsurge of artistic activity in Harlem in the twenties fulfilled Du Bois’s prophecy, although the elitism implicit in the phrase “Talented Tenth” would prove problematic. Music was essential to the Re naissance spirit, and Du Bois, the philosopher Alain Locke, and the poet James Weldon Johnson all argued that black composers should avail themselves of European forms, even as they explored the native African-American tradition. Cook himself wrote in 1918: “Developed Negro music has just begun in America. The colored American is finding himself. He has thrown aside puerile imitations of the white man. He has learned that a thorough study of the masters gives knowledge of what is good and how to create. From the Russian he has learned to get his inspiration from within; that his inexhaustible wealth of folklore legends and songs furnish him with material for compositions that will establish a great school of music and enrich musical literature.”

Still, Cook could not break into “straight” composition. In the second de cade of the century, he became a bandleader, putting together a sharp group called the New York Syncopated Orchestra, which later toured Europe under the name Southern Syncopated Orchestra. Although Cook never felt comfortable with jazz—improvisation grated against his conservatory training—he highlighted the new sounds that were emerging from New Orleans, and hired the young clarinet virtuoso Sidney Bechet as his star soloist. The conductor Ernest Ansermet, who took an avid interest in jazz just as it was developing, heard Cook’s orchestra play in 1919 and, with an alertness that has won him a place of honor in anthologies of jazz writing, acclaimed Bechet as a “genius” and Cook as a “master in every respect.” Back in 1893 Anton Rubin-stein had predicted that Negro musicians could form “a new musical school” in twenty-five or thirty years. Twenty-five years later, Ansermet perceived in Bechet’s and Cook’s performances “a highway that the world may rush down tomorrow.”

Cook was hardly the only black musician to turn from classical study to a popular career. Many classically trained black musicians played significant roles in early jazz, giving the lie to the simplistic and racist idea that it was a purely instinctive, illiterate form. Will Vodery worked as a librarian for the Philadelphia and Chicago orchestras in his youth and showed promise as a conductor, but his career took off only when Florenz Ziegfeld, the master showman of Broadway, hired him to arrange music for his Follies. James Reese Europe trained on the violin but found no work when he arrived in New York in 1903; instead, he began playing bar piano, conducting theatricals, and leading bands. His all-black Clef Club Orchestra and Hell Fighters band introduced a broad audience to syncopated music that was a step or two away from jazz. Fletcher Henderson, Ellington’s future rival for the crown of king of swing, started out as a classical piano prodigy; when he went to work with Ethel Waters in New York, he had to learn jazz piano by listening to James P. Johnson piano rolls. Johnson himself, Harlem’s reigning stride pianist, had compositional aspirations that were only partly fulfilled. In a later generation, Billy Strayhorn, destined to win fame as Ellington’s chief collaborator, shone as a composing prodigy in his youth and wowed his high-school classmates with a Concerto for Piano and Percussion.

The same scenario kept repeating. Middle-class parents would send their sons and daughters to Oberlin or Fisk or the National Conservatory, hoping that they could achieve the wonderful things that Dvořák had forecast for African-American music. Hitting the wall of prejudice, these young creative musicians would turn to popular styles instead—first out of frustration, then out of ambition, finally out of pride. The youngest players embraced jazz as their birthright; they gave little thought to Dvořák’s old fantasy of Negro symphonies. Cook, however, never forgot the ambitions that he had nursed as a boy, when he stood on Lookout Mountain. He still dreamed of a “black Beethoven, burned to the bone by the African sun.”

Charles Ives

Inscribed above the stage of Symphony Hall in Boston, one of America’s great music palaces, is the name BEETHOVEN, occupying much the same position as a crucifix in a church. In several late-nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century concert halls, the names of the European masters appear all around the circumference of the auditorium, signifying unambiguously that the buildings are cathedrals for the worship of imported musical icons. Early in the century, any aspiring young composer who sat in one of these halls—a white male, needless to say, blacks being generally unwelcome and women generally not taken seriously—would likely have fallen prey to pessimistic thoughts. The very design of the place militated against the possibility of a native musical tradition. How could your name ever be carved alongside Beethoven’s or Grieg’s when all available spaces were filled? The fact that so many American composers still came forward is a tribute to the willfulness of the species.

Charles Ives was one such stubborn youth. He came from a distinguished New England family, the descendant of a farmer who arrived in Connecticut fifteen years after the voyage of the Mayflower. His grand parents George White Ives and Sarah Hotchkiss Wilcox Ives had connections to the Transcendentalists, the royalty of American intellectual life; Emerson himself supposedly once spent a night in their Danbury house. Ives’s father was the bandleader George Ives, about whom little is known beyond Charles’s not always reliable recollections. Whether the father really anticipated the son’s experiments is impossible to determine, but one famous tale is corroborated by eyewitness testimony: the bandleader once marched two bands past each other for the simple joy of hearing them in cacophonous simultaneity. Ives also remembers that he and his brothers were directed to sing Stephen Foster’s plantation tune “Old Folks at Home” in the key of E-flat while George played the accompaniment in C.

Charles attended Yale College, where he studied composition with Horatio Parker, under whose tutelage he produced an expert, Dvořákian four-movement symphony. In 1898 the young composer went to New York, where he worked a day job at the Mutual Life Insurance Company and played the organ and directed music at the Central Presbyterian Church. (He had been an expert organist since his teens, using the instrument to experiment with spatial effects and multiple layers of activity.) In 1902 Ives attracted positive attention with a cantata titled The Celestial Country. The Musical Courier detected “undoubted earnestness in study and talent for composition”; the Times called the new work “scholarly and well made,” “spirited and melodious.” Ives seemed poised for a distinguished career. First he would study with an important name in Europe, then he would find a position on an Ivy League faculty.

Just one week after the successful premiere, however, Ives suddenly resigned his church position, and subsequently vanished from the musical scene. Why he did so remains a mystery. Perhaps he had been expecting a more ecstatic reception to his debut; tellingly, he later scrawled the words “Damn rot and worse” over one of the reviews of The Celestial Country. Biographers have added speculation that this athletic young male, Yale’s “Dasher” Ives, had a sort of macho hang-up with respect to American classical-music culture, which, to his eyes, appeared to be an “emasculated art,” controlled by women patrons, effeminate men, and fashionable foreigners (“pussies,” “sissies,” “pansies,” and so on). More prosaically, Ives may have lost faith when an acquaintance was picked to teach at Yale as Parker’s heir apparent.

Instead, Ives chose to make his living in life insurance, at which he proved remarkably adept. He was a proponent of the hard sell, skilled at getting people to buy policies that they didn’t know they wanted. He didn’t go door-to-door himself; his job was to think up sales techniques that could be passed along to a network of freelance brokers. Ives codified his innovations in the pamphlet The Amount to Carry, which laid out a sales pitch “simple enough to be understood by the many, and complex enough to be of some value to all!” Ives told each salesman to plant himself firmly in front of a potential customer’s door and “knock some BIG ideas into his mind.”