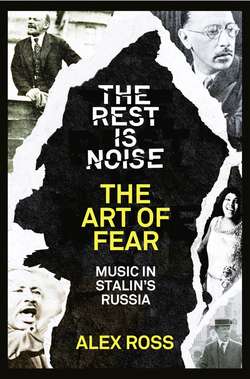

Читать книгу The Rest Is Noise Series: The Art of Fear: Music in Stalin’s Russia - Alex Ross - Страница 6

ОглавлениеTHE ART OF FEAR

Music in Stalin’s Russia

On January 26, 1936, Joseph Stalin, the general secretary of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik), went to the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow for a performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The Soviet dictator often attended opera and ballet at the Bolshoi, where he made a show of being inconspicuous; he preferred to take a seat in the back row of Box A, just before the curtain rose, and positioned himself behind a small curtain, which concealed him from the audience without obstructing his view of the stage. Phalanxes of security and a general heightening of tension would signal to experienced observers that Stalin was in the hall. On this night, Shostakovich, the twenty-nine-year-old star of Soviet composition, had been officially instructed to attend. He sat facing Box A. Visible in front were Vyacheslav Molotov, Anastas Mikoyan, and Andrei Zhdanov, all of them members or candidate members of the Politburo. According to one account, they were laughing, talking among themselves, and otherwise enjoying their proximity to the man behind the curtain.

Stalin had lately taken an interest in Soviet opera. On January 17 he had seen Ivan Dzerzhinsky’s The Quiet Don, and liked it enough to summon the composer to his box for an interview, commenting that Soviet opera should “make use of all the latest devices of musical techniques, but its idiom should be close to the masses, clear and accessible.” Lady Macbeth, the tale of a vaguely Lulu-like Russian house-wife who leaves a string of bodies in her wake, did not meet these somewhat ambiguous specifications. Stalin left the hall either before or during the final act, taking with him Comrades Molotov, Mikoyan, and Zhdanov. Shostakovich confided to his friend Ivan Sollertinsky that he, too, had been hoping to receive an invitation to Box A. Despite vigorous applause from the audience, the composer left feeling “sick at heart,” and he remained so as he boarded a train for the northern city of Arkhangel’sk, where he was scheduled to perform.

Two days later, one of the great nightmares of twentieth-century cultural history began riding down on the nervous young composer. Pravda, the official Communist Party newspaper, printed an editorial with the headline “Muddle Instead of Music,” in which Lady Macbeth was condemned as an artistically obscure and morally obscene work. “From the first moment of the opera,” the anonymous author wrote, “the listener is flabbergasted by the deliberately dissonant, muddled stream of sounds.” Shostakovich was said to be playing a game that “may end very badly.” The last phrase was chilling. Stalin’s Terror was imminent, and Soviet citizens were about to discover, if they did not know already, what a bad end might mean. Some would be pilloried and executed as enemies of the people, some would be arrested and killed in secret, some would be sent to the gulags, some would simply disappear. Shostakovich never shook off the pall of fear that those six hundred words in Pravda cast on him.

A few weeks before “Muddle Instead of Music” was published, a familiar face appeared again in Moscow. Sergei Prokofiev, who had been living outside Russia since 1918, arrived with his wife, Lina, to celebrate New Year’s Eve. According to Harlow Robinson’s biography, Prokofiev attended a party at the Moscow Art Theatre and remained there until five in the morning. Since 1927, the former enfant terrible of Russian music had returned many times to his native land; now he decided to live in Moscow full-time. He was well aware that Soviet artists were subject to censorship, but he chose to think that such restrictions would not apply to him. He was, at this time, forty-four years old, at the height of his powers and in good health. He, too, would endure a long string of humiliations, and was not granted the satisfaction of outliving Stalin. In a twist that would seem too heavy-handed in a novel, Prokofiev died on March 5, 1953, about fifty minutes before Stalin breathed his last.

The period from the mid-thirties onward marked the onset of the most warped and tragic phase in twentieth-century music: the total politicizing of the art by totalitarian means. On the eve of the Second World War, dictators had manipulated popular resentment and media spectacle to take control of half of Europe. Hitler in Germany and Austria, Mussolini in Italy, Horthy in Hungary, and Franco in Spain. In the Soviet Union, Stalin refined Lenin’s revolutionary dictatorship into an omnipotent machine, relying on a cult of personality, rigid control of the media, and an army of secret police. In America, Franklin D. Roosevelt was granted extraordinary executive powers to counter the ravages of the Depression, leading conservatives to fear an erosion of constitutional process, particularly when federal arts programs were harnessed to political purposes. In Germany, Hitler forged the most unholy alliance of art and politics that the world had ever seen.

For anyone who cherishes the notion that there is some inherent spiritual goodness in artists of great talent, the era of Stalin and Hitler is disillusioning. Not only did composers fail to rise up en masse against totalitarianism, but many actively welcomed it. In the capitalist free-for-all of the twenties, they had contended with technologically enhanced mass culture, which introduced a new aristocracy of movie stars, pop musicians, and celebrities without portfolio. Having long depended on the largesse of the Church, the upper classes, and the high bourgeoisie, composers suddenly found themselves, in the Jazz Age, without obvious means of support. Some fell to dreaming of a political knight in shining armor who would come to their aid.

The dictators played that role to perfection. Stalin and Hitler aped the art-loving monarchs of yore, pledging the patronage of the centralized state. But these men were a different species. Coming from the social margins, they believed themselves to be perfect embodiments of popular will and popular taste. At the same time, they saw themselves as artist-intellectuals, members of history’s vanguard. Adept at playing on the weaknesses of the creative mind, they offered the seduction of power with one hand and the fear of destruction with the other. One by one, artists fell in line.

Untangling composers’ relationships with totalitarianism is a tricky exercise. For a long time discussion of Shostakovich revolved around the issue of whether he was an “official” composer who produced propaganda on command or a secret dissident who encoded anti-Stalinist messages in his scores. Likewise, people have pondered whether Prokofiev knowingly aligned himself with Stalinist aesthetics in order to advance his career or returned to the Soviet Union in a state of unknowing naïveté. Similar questions have been posed about Richard Strauss’s murky, unheroic behavior in the Nazi period, but they are the wrong ones to ask.

Black-and-white categories make no sense in the shadowland of dictatorship. These composers were neither saints nor devils; they were flawed actors on a tilted stage. In some extra verses for “Die Moritat vom Mackie Messer,” Bertolt Brecht wrote, “There are those who dwell in darkness, there are those who dwell in light.” Most dwell in neither place, and Shostakovich speaks for all.

Revolution

Lenin, the prototype of the twentieth-century dictator, had favorite authors and composers, but he was too rigorous a materialist to bother much with art. He had little patience for the avant-garde, and once had a fit when futurists painted May Day colors on the trees in the Aleksandrovsky gardens. Music he regarded as a bourgeois placebo that covered up the sufferings of mankind. In a conversation with Maxim Gorky, he extolled the power of Beethoven, but added, “I can’t listen to music too often. It affects your nerves, makes you want to say stupid nice things, and stroke the heads of people who could create such beauty while living in this vile hell.” Nevertheless, he tolerated the activities of various avant-garde factions, which lent a veneer of sophistication to the thuggery of Bolshevism in its early days.

Lenin’s chief artistic functionary was Anatol Lunacharsky, who from 1917 to 1929 headed the Commissariat of Enlightenment. Lunacharsky was not unlike Leo Kestenberg in Berlin—a peculiarly smart and broad-minded bureaucrat with a poor understanding of political reality. A philosopher by training, an observant critic of Dostoevsky and other authors, something of a mystic, Lunacharsky believed that a revolution in society should go hand in hand with a revolution in art. Communism, in his view, was a new kind of secular rite, for which art should supply the chant, icons, and incense. The poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, among the first to join Lunacharsky’s crusade, joined him in believing that Communism could wipe out the “old aesthetic junk.” Mayakovsky’s poetry railed against bourgeois art in all its manifestations: “Spit on rhymes and arias and the rose bush and other such mawkishness from the arsenal of the arts … Give us new forms!” The epoch-making actor and director Vsevolod Meyerhold, who had dismantled the artifice of naturalistic theater shortly after the turn of the century, hoped that the revolution would breathe life into his dream of a “people’s theater.” As in Weimar, artists embraced Communism because it promised to cut the throat of a common enemy, the de cadent bourgeoisie.

To lead Muzo, the music section of the Commissariat of Enlightenment, Lunacharsky appointed Arthur Lourié, a bohemian composer who was writing dissonant, spiritually charged music in the manner of Alexander Scriabin. Under the aegis of these two unlikely bureaucrats, a period of “anything goes” ensued. Russian composers of the twenties produced some of the wildest sounds of the time, in many cases out-cacophonizing their Western European counterparts. Alexander Mosolov’s orchestral sketch The Iron Foundry used grinding beats and layered rhythms to mimic the action of a factory. Nikolai Roslavetz composed according to a “new system of tone organization,” building dense chromatic textures from “synthetic chords.” Lev Theremin pioneered the eerily wailing electronic instrument that later bore his name. Georgi Rimsky-Korsakov, grandson of the great Rimsky, formed the Society for Quarter-Tone Music. The pièce de résistance of the era was Arseny Avraamov’s Symphony for Factory Whistles, which achieved a memorable performance in the port of Baku in 1922: “The Internationale” and “La Marseillaise” were sounded by an orchestra of factory sirens, artillery, machine guns, bus and car horns, shunting engines, and the foghorns of the Caspian Fleet.

Lunacharsky’s notion of Communism as an artistically enhanced mass religion violated Leninist thought, and the Bolshevik arts utopia inevitably ran into difficulties. Experimentalism proved to have no propaganda value, except when it came to advertising Soviet culture to the West. Various factions of self-styled proletarian artists attacked the modernist tendency and demanded simple, popular entertainment in its place. Lunacharsky pleaded for multiple perspectives and freedom of expression—“Let the worker hear and evaluate everything, the old and the new”—but he steadily lost ground as the twenties went on. The Commissariat of Enlightenment crumbled into a morass of competing bureaucracies, and the Party eventually shunted the arts apparatus into the ideology and propaganda section.

When Stalin assumed sole power in 1929, artists found themselves in a more conspicuous and also more dangerous position. Recent biographies, such as Simon Sebag Montefiore’s, have emphasized Stalin’s intelligence and charm alongside his well-known cunning and brutality. He was a well-read man with a taste not only for canonical literature but also for the modern satires of Mikhail Bulgakov and Mikhail Zoshchenko. Although Stalin detested the radical styles that had prospered during the Lunacharsky period, he promoted the idea of a “Soviet modernism,” a school of art that would embody the power and prowess of the new proletarian state. His musical tastes were narrow but not vulgar. He patronized the Bolshoi, listened to classical music on the radio, and sang folk songs in a fine tenor voice. He monitored every recording made in the Soviet Union, writing judgments on the sleeves (“good,” “so-so,” “bad,” or “rubbish”), and accumulated ninety-three opera recordings.

Stalin liked to use the telephone, and had an unnerving habit of calling artists in the middle of the night. Sometimes, like a Roman emperor in an indulgent mood, he would grant his petitioners an extraordinary favor. Others would be told to expect a call that never came, and they would interpret the silence as an omen of disaster. Soon might come the dreaded knock at the door—“sharp, unbearably explicit,” wrote Nadezhda Mandelstam, in her great memoir Hope Against Hope—which heralded the arrival of the NKVD. Stalin’s manipulations created a new species of fear. “The fear that goes with the writing of verse has nothing in common with the fear one experiences in the presence of the secret police,” Mandelstam wrote. “Our mysterious awe in the face of existence itself is always overridden by the more primitive fear of violence and destruction.” As her husband, Osip, used to say, in the Soviet era the second kind of fear was all that was left.

Young Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich made a nerve-racking first impression. His face was ashen in hue, his eyes darting furtively behind thick glasses. His body constantly twitched, as if something were struggling to escape from it. When he talked, his speech doubled back on itself, phrases repeating themselves like anxious mantras. In intimate gatherings, with the aid of a favorite vodka, Shostakovich showed another side of his personality—antic, caustic, passionate. He was capable of puppy-dog-like tenderness and also of forbidding anger.

Laurel Fay, in her authoritative Shostakovich biography, quotes a verbal portrait that Zoshchenko made of the composer in the early 1940s: “It seemed to you that he is ‘frail, fragile, withdrawn, an infinitely direct, pure child.’ That is so. But if it were only so, then great art (as with him) would never be obtained. He is exactly what you say he is, plus something else—he is hard, acid, extremely intelligent, strong perhaps, despotic, and not altogether good-natured (although cerebrally good-natured) … In him, there are great contradictions. In him, one quality obliterates the other. It is conflict in the highest degree. It is almost a catastrophe.”

Shostakovich was born on September 25, 1906. From an early age he showed an astounding aptitude for music, grasping basic theory and notation almost without formal instruction. In 1919, at the age of thirteen, he enrolled in what was then called the Petrograd Conservatory, where his abilities mesmerized Alexander Glazunov, the alcoholically dilapidated but still formidable head of the institution. Glazunov made sure that the young man stayed well fed during the lean years of Lenin’s New Economic Policy. In exchange, Shostakovich’s father supplied Glazunov with beverages illegally obtained from the Bureau of Weights and Measures.

There was a history of radical-left commitment in Shostakovich’s family, and his parents welcomed the Russian Revolution in its initial stages. But they were not Bolsheviks, and took fright when Lenin’s forces swept aside the more liberal government of Alexander Kerensky. Shostakovich, then eleven, imitated his parents’ politics. In the early weeks of the revolution he wrote a Funeral March in honor of fallen anti-tsarist fighters, but the following year he either renamed that piece or wrote a new one in memory of two early victims of Bolshevik terror. Even in prepubescence, it seems, he was ambiguous.

As a teenager, Shostakovich developed a taste for the iconoclastic poems of Mayakovsky, but not necessarily for the politics behind them. Only toward the end of his studies at the conservatory did Shostakovich finally come face-to-face with the absurdities of Soviet ideology: when a fellow student was asked to explain the socio-economic dimensions of the music of Chopin and Liszt, Shostakovich burst out laughing. Later, once he had become a prominent figure in the music-education system, Shostakovich would go out of his way to help students who flailed about when confronted with the political portions of the syllabus. At one oral exam, Shostakovich found himself sitting beneath a large poster that said, “ ‘Art belongs to the People.’—V. I. Lenin.” With a helpful upward tilt of the head, he posed the question “To whom does art belong?”

Shostakovich was never politically naive. While still a student in Petrograd, or Leningrad, as it was renamed in 1924, the composer gained an influential ally in Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a Red Army hero who was infamous in Tambov Province for having employed poison gas against anti-Bolshevik peasants. According to Shostakovich’s friend and chronicler Isaak Glikman, Tukhachevsky was “a man of great education and intelligence” who assiduously attended concerts, played violin, and made instruments by hand. He offered to find the young composer a room and a job in Moscow. Fortunately, perhaps, in view of Tukhachevsky’s eventual fate in the Terror, Shostakovich elected to remain in his home city.

Shostakovich’s youthful assurance blazed forth in his First Symphony, which the Leningrad Philharmonic introduced to frenetic applause on May 12, 1926. It is a work of unusually gripping narrative drive, careening from one vertiginous climax to the next. The musical language is mobile and flexible, making intermittent use of a system that the Russian theorist Boleslav Yavorsky had set forth in his 1908 book, The Construction of Musical Speech, whereby various modes, ranging from the familiar diatonic scale to Rimsky’s octatonic scale, and so forth, are played off each other. The symphony quickly found an international audience, and none other than Alban Berg wrote the composer a congratulatory letter.

By way of reward, Shostakovich received a well-paying commission from the Department of Agitation and Propaganda of the State Publishers’ Music Section for a grand choral-orchestral work to honor the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. The piece was initially titled To October, and later became the Second Symphony. The opening section evokes prerevolutionary days with a snapshot of economic chaos: the strings are divided into seven parts, each moving in an independent rhythm. A little later nine caterwauling winds go every which way, perhaps representing the Silver Age intellectuals. Then a factory whistle (F-sharp) signals the arrival of Bolsheviks, and high-modern complexity gives way to elemental hymns. Although the text is banal, Shostakovich whips up a militant frenzy that anticipates the most potent of Hanns Eisler’s “battle songs.” The Third Symphony, subtitled “The First of May,” follows the same template, redeeming abstraction with bombast.

Despite the slow decline of Lunacharsky’s system, the Soviet musical scene remained varied and vibrant throughout the twenties. Without leaving Russia, Shostakovich was able to soak up various foreign influences, because the West came to him. Hindemith, Krenek, Berg, and Milhaud all paid visits to the new Soviet paradise; Der ferne Klang, Wozzeck, and Jonny spielt auf were staged; and Sam Wooding’s Negro revue Chocolate Kiddies toured Russia in 1926, giving Soviet avant-gardists a taste of jazz. On a brief visit to Berlin the following year, Shostakovich experienced the magic of Weimar culture first-hand. He was soon echoing the antisentimental, “objectivist” tone of Hindemith, Weill, Bartók, and middle-period Stravinsky. Shrill winds, curt brass, and jangling xylophones cut through the traditional luxuriousness of Russian strings.

Shostakovich also absorbed the unconventional narrative strategies of Soviet artists and theorists of the period, delighting in effects of discontinuity, montage, parody, self-conscious artificiality, and the “estrangement” of familiar styles and forms. Meyerhold, the titan of radical theater, recognized the young composer as a kindred spirit and asked him to write music for several of his productions—notably for his 1929 staging of Mayakovsky’s play The Bedbug.

In the same year, Shostakovich began what would turn out to be a lifelong collaboration with Grigori Kozintsev, who, together with Leonid Trauberg, had launched an avant-garde theater and film collective called Factory of the Eccentric Actor, or FEKS. In typical twenties fashion, FEKS aped the madcap pacing of the circus, the variety theater, and American movies, and Shostakovich followed suit. His score for Kozintsev and Trauberg’s silent film New Babylon, a politicized love story set in the period of the Paris Commune, avoided direct illustration of on-screen action and jarred the viewer with bizarre juxtapositions. For example, when the Communards are killed by firing squad at the end, Shosta kovich responds with a distorted version of the high-kicking can-can from Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld. Such paradoxes fulfilled an idea that Sergei Eisenstein and colleagues had advanced in the summer of 1928: “The first experiments in sound [in film] must aim at a sharp discord with the visual images.”

Shostakovich’s radical period culminated in the opera The Nose, based on Nikolai Gogol’s story of an appendage that walks away from its owner and assumes an exalted social rank. Percussion interludes, trombone glissandos, and grotesque dance rhythms are deployed in what purports to be a mockery of bourgeois values, although the composer’s dependence on the stock devices of the Western avant-garde undercuts the message. If Shostakovich had moved to Berlin at this time, he might have had trouble standing out from the general throng of spiky young composers.

It was after the premiere of The Nose—in concert form, in June 1929—that Shostakovich found himself first accused of “formalism.” The word was Soviet shorthand for any style that smacked too strongly of Western modernism. The strike came from the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM), which had made it its mission to extirpate all remnants of bourgeois musical culture. The Nose vanished from Soviet stages, not to be seen again on Russian soil until 1974. Shostakovich buried himself in film and theater work, dutifully using his music to portray the eternal battle between good Soviets and their “class enemies.” The ballets The Golden Age and The Bolt expose, respectively, the decadence of Western competitors at a football match and the nefarious activities of “slackers,” “tipplers,” and “saboteurs.” The films The Golden Mountains and The Counterplan unmask capitalist bosses and wreckers of industry. Kozintsev and Trauberg’s film Alone follows a Leningrad schoolteacher into farthest Siberia, where landowning peasants are obstructing the Soviet experiment. Stalin approved these films for wide release in late 1931, and Shostakovich’s name probably first came to his attention at the screenings. The dictator is known to have loved “The Song of the Counterplan,” which went on to become one of the iconic melodies of the Soviet age.

In November 1931, Shostakovich made what seemed a brave move. Fed up with the agitations of the proletarians, he issued a manifesto, “Declaration of a Composer’s Duties,” stating that demands for songfulness in Soviet music and theater were having a ruinous effect on composers. In fact, as Shostakovich may well have been aware, the Party was about to disavow the proletarian line; the following April, RAPM was dissolved, and the new Union of Soviet Composers took its place. You can sense a certain cackling quality in the music that Shostakovich wrote for Nikolai Akimov’s irreverent 1932 production of Hamlet, which opened in Moscow a month after the demise of RAPM. In Act III, Scene 2, Hamlet accuses Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of trying to play him like a pipe, and in the Akimov production the prince dramatized his contempt by lowering a flute to his buttocks. At that moment, Shostakovich had a piccolo in the orchestra pipe out Alexander Davidenko’s mass song “They Wanted to Beat Us, to Beat Us,” a favorite of the proletarian faction.

After years of collectivization, industrialization, and famine, the Soviet populace was feeling rebellious, and in the early thirties Stalin tried to placate his subjects by promising new comforts and freedoms. Artists were deputized to broadcast the message that “life is getting better,” as Stalin eloquently put it. To this end, artists’ lives were made better, at least in the material sense. The Union of Soviet Composers supplied composers with health plans, sanatoriums, and a cooperative building in Moscow. At an October 1932 gathering at Maxim Gorky’s Moscow mansion, Stalin mused aloud that writers should be “engineers of human souls,” and the writers debated among themselves what he meant. From the meeting emerged the concept of socialist realism, according to which Soviet artists would depict the people’s lives both realistically and heroically, as if from the standpoint of the socialist utopia to come. Established nineteenth-century forms such as the novel, the epic drama, the opera, and the symphony were deemed suitable vehicles of expression, although they required thorough renovation in line with Soviet thought. The Party theorist Nikolai Bukharin, at the Writers’ Congress of 1934, offered a more elaborate definition of socialist realism, calling for stories of “tragedies and conflicts, vacillations, defeats, the struggle of conflicting tendencies.”

Shostakovich’s first contribution to the new phase in Soviet art was Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The libretto, based loosely on a story by Nikolai Leskov, tells of Katerina Ismailova, a strong-willed woman in a provincial town in 1860s Russia. Variously bored and oppressed by the men in her life, she finds it convenient to dispose of them. She first kills her father-in-law, Boris, whom Shostakovich identified as a “typical master kulak,” or wealthy landowning peasant, in order to save herself from his repulsive advances. She then connives with her lover, Sergei—a “future kulak”—to kill her jealous, abusive husband, Zinovi. The last act takes place in a Siberian prison camp, to which the lovers have been consigned. When Sergei’s eyes wander to another woman, Katerina drowns herself in a river, taking her rival with her.

What made this scenario politically timely was that in 1929 Stalin had launched a genocidal campaign of “liquidating the kulaks as a class,” whether by execution, imprisonment, or deportation. Shostakovich himself gestured toward the subtext: “In Lady Macbeth I wanted to unmask reality and to arouse a feeling of hatred for the tyrannical and humiliating atmosphere in a Russian merchant’s house-hold.” These “petty,” “vulgar,” “cruel,” “greedy” merchants are Soviet counterparts to the hook-nosed banker Jews who appeared in Nazi cartoons of the same period. Robert Conquest estimates that three million people died as a result of the “dekulakization” program.

Seen from one angle, then, Lady Macbeth is nearly an opera in the service of genocide. In other ways, however, it is anything but a propaganda work. The composer called it a “Tragedy-Satire,” and that ambiguity sets the tone; nothing can be taken entirely at face value. Extending Eisenstein’s notion of discord between sound and image, Shostakovich uses cartoonish musical stereo types to undermine rather than illustrate the action onstage. The attempted rape of Katerina’s cook, Aksinya, for example, plays out against a manic galop worthy of Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies. Boris’s lust for Katerina is represented by a drunken Viennese waltz. As the opera goes on, hard-hearted grotesquerie gives way to spells of confession and lamentation. When Boris is killed in Act II, the musical reaction is at first icily unsympathetic, but after a priest offers to say a requiem for the merchant, the orchestra takes the stage with a grandiose dirge in the form of a passacaglia, rather plainly modeled on the D-minor threnody in Berg’s Wozzeck. The dramatic function of this music is obscure. Is it, unexpectedly, a statement of sympathy for the awful Boris? Does it express internal turmoil on the part of Katerina? The general grinding operation of fate? What ever it means, it fails to advance the stated program of stirring hatred for the kulaks.

The opera makes more sense as a fable of the madness of love, of the disorienting power of sexuality. It was written under the spell of the physicist Nina Varzar, whom Shostakovich married in 1932; the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya thought that Katerina was an exaggerated depiction of Nina’s passionate nature. But the madness may really have been Shostakovich’s own; two years later, he would fall in love with the young translator Elena Konstantinovskaya, precipitating a crisis in his marriage, and his romantic life would display tragicomic aspects ever after. The writer Galina Serebryakova recalled: “[Shostakovich] was thirsting to re create the theme of love in a new way, a love that knew no boundaries, that was willing to perpetrate crimes inspired by the devil himself, as in Goethe’s Faust.” Katerina is too consumed by her desires to register the absolute corruption around her; instead, like Salome, she exposes the insanity of her world by embodying it to excess. In this sense, the opera becomes an altogether darker kind of monument to Stalin’s world.

Terror

Shostakovich was not the first Soviet composer to be censured by the state. In 1935, Gavriil Popov, a greatly gifted artist who had studied alongside Shostakovich at the Leningrad Conservatory, unveiled his First Symphony, an immensely forceful hour-long work to which Shostakovich’s subsequent symphonies owe a more than minor debt. After the premiere, a censorship board denounced Popov’s symphony as a work of “class-enemy character” and banned further performances. With Shosta kovich’s support, Popov succeeded in having the ruling overturned. But the renewed assault on musical and artistic formalism in 1936 meant that the piece was taken out of circulation again. Popov began a long descent into alcoholism and mediocrity. The difference between his fate and Shostakovich’s says much about the latter’s power of endurance, his ability to preserve his musical self under potentially annihilating pressure.