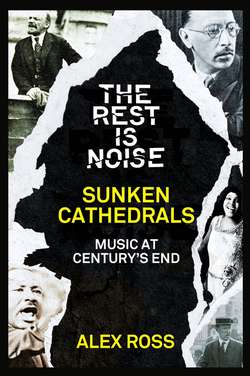

Читать книгу The Rest Is Noise Series: Sunken Cathedrals: Music at Century’s End - Alex Ross - Страница 7

After the End

ОглавлениеThis has been a book about the fate of composition in the twentieth century. The temptation is strong to see the overall trajectory as one of steep decline. From 1900 to 2000, the art experienced what can only be described as a fall from a great height. At the beginning of the century, composers were cynosures on the world stage, their premieres mobbed by curiosity seekers, their transatlantic progress chronicled by telegraphic bulletins, their deathbed scenes described in exquisite detail. On Mahler’s last day on earth, the Viennese press reported that his body temperature was wavering between 37.2 and 38 degrees Celsius. A hundred years on, contemporary classical composers have largely vanished from the radar screen of mainstream culture. No one whispers “Der Adams!” as the composer of El Niño walks the streets of Berkeley.

From a distance, it might appear that classical music itself is veering toward oblivion. The situation looks especially bleak in America, where scenes from prior decades—Strauss conducting for thousands in Wanamaker’s department store, Toscanini playing to millions on NBC radio, the Kennedys hosting Stravinsky at the White House—seem mythically distant. To the cynical onlooker, orchestras and opera houses are stuck in a museum culture, playing to a dwindling cohort of aging subscribers and would-be elitists who take satisfaction from technically expert if soulless renditions of Hitler’s favorite works. Magazines that once put Bernstein and Britten on their covers now have time only for Bono and Beyoncé. Classical music is widely mocked as a stuck-up, sissified, intrinsically un-American pursuit. The most conspicuous music lover in modern Hollywood film is the fey serial killer Hannibal Lecter, moving his bloody fingers in time to the Goldberg Variations.

Seen from a more sympathetic angle, the picture is quite different. Classical music is reaching far larger audiences than it has at any time in history. Tens of millions show up from night to night in opera houses, concert halls, and festival grounds. Huge new audiences have materialized in East Asia and South America. While the repertory is preternaturally resistant to change, it is being permeated by twentieth-century music. Stravinsky’s Rite, Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, and Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony are beloved orchestral showpieces; works of Strauss, Janáček, and Britten have joined Mozart and Verdi in the opera repertory. Young audiences crowd into small halls to hear Elliott Carter’s string quartets or Xenakis’s stochastic constructions. Living composers such as Adams, Glass, Reich, and Arvo Pärt have acquired a semblance of a mass following. And a few farsighted orchestras have put modern repertory front and center: in 2003, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, under the visionary direction of Esa-Pekka Salonen, inaugurated Walt Disney Concert Hall with a program that included Ligeti’s Lux aeterna, Ives’s The Unanswered Question, and, naturally, the Rite. As the behemoth of mass culture breaks up into a melee of subcultures and niche markets, as the Internet weakens the media’s stranglehold on cultural distribution, there is reason to think that classical music, and with it new music, can find fresh audiences in far-flung places.

There is little hope of giving a tidy account of composition in the second fin de siècle. Styles of every description—minimalism, post-minimalism, electronic music, laptop music, Internet music, New Complexity, Spectralism, doomy collages and mystical meditations from Eastern Europe and Russia, appropriations of rock, pop, and hip-hop, new experiments in folkloristic music in Latin America, the Far East, Africa, and the Middle East—jostle against one another, none achieving supremacy. Some have tried to call the era postmodern, but “modernism” is already so equivocal a term that to affix a “post” pushes it over the edge into meaninglessness. In retrospect, modernism, in the sense of a unified vanguard, never existed. The twentieth century was always a time of “many streams,” a “delta,” in the wise words of John Cage. What follows is an aerial tour of an ever-changing landscape.

Composing remains, as Thomas Mann’s Devil says, “desperately difficult.” Although vast quantities of music are being written down day by day—national websites display lists of 450 composers in Australia, 650 composers in Canada, several thousand in the Nordic countries—few of them have found an audience outside a relatively limited clique of new-music fanciers. Some specialize in “music for use,” writing for church choirs or collegiate wind bands or the soundtracks of video games. The majority make a living by teaching composition, and their students usually become teachers themselves. They may sometimes ask, with the title character of Hans Pfitzner’s Palestrina, “What is it for?” They have read in books that their fore-bears humbled kings, electrified crowds, forged nations. Sooner or later they realize that modern popular culture has no place for a composer hero. The most celebrated composers are sometimes the unhappiest; György Ligeti, in his last years, was reportedly haunted by the feeling that he would be forgotten after his death, that he had outlived the age in which music mattered.

Perhaps Ligeti was right; perhaps classical composition is being sustained past its date of expiration by the stubborn determination of those who perform it, those who support it, and, above all, those who write it. More likely, though, a thousand-year-old tradition won’t expire with the flipping of a calendar or the aging of a baby-boom cohort. Confusion is often a prelude to consolidation; we may even be on the verge of a new golden age. For now, the art is like the “sunken cathedral” that Debussy depicts in his Preludes for Piano—a city that chants beneath the waves.