Читать книгу Conversations with Diego Rivera - Alfredo Cardona Peña - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

IN SEPTEMBER OF 1948, Diego Rivera escaped being lynched by a mob of hotheads stoning his house in Coyoacán. In his mural at the Prado Hotel, in Mexico City, the artist had reproduced a phrase by the liberal writer Ignacio Ramírez (1818-1879) sufficiently strong to ignite the ire of malcontents.

The phrase that provoked the riot read, in bold letters: God doesn’t exist. The hotel management, frightened, ordered the mural to be covered up. The title of the mural was, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central Park. The then archbishop of Mexico, Doctor Luis María Martinez, for his part, refused to bless the new hotel and the clergy attacked Rivera from the pulpit. The word spread that the building was damned and destined to burn. Rivera was delighted.

Many years before, when the artist was in Toledo, Spain (1907), the legend spread among folk that “he fed on the bones of children.” That may have been what led to the famous attempt on his life.

He shook up the newspapers twenty years ago spreading the version that he was a cannibal. I heard him say, to a group of students in the state of Puebla, “human meat has a slightly sweet taste, superior to that of any edible animal.” The students were horrified. Diego laughed to himself.

When his third wife, Frida Kahlo, that extraordinary painter, died, her wake was held in the Palace of Bellas Artes, as a proper homage to her work. Diego arrived and ordered the unfurling of a flag with the hammer and sickle, and the Communists, headed by him, sang “The Internationale.” Such was the scandal that it led to the downfall of the director of the National Institute of Bellas Artes, the writer Andrés Iduarte. Rivera rubbed his hands in glee.

One time I asked him, “how would you decorate the Mexico City Cathedral?” The reply was devastating: “The day that Mexico’s cathedral is turned into a useful building, no longer the provider of opium to the people, and it is turned into a discussion center, a popular museum, a garrison, a library or grain cellar, I would love nothing more than to decorate it. If Mexican Catholics had any sense, they would ask their bankers of the Committee on Decorum to hire José Clemente Orozco or myself to work on a series of works that would turn the cathedral into a visual center of such importance that those hotels whose investors are the same bankers from the Committee, would do the most fantastic business of their lives.”

Because of such views, Diego Rivera was continuously insulted in the press, in public when he ventured to espouse one of his radical theories, and privately when traditional notions were offended by his declarations, manifestos or communications.

But when the government organized the exposition of his complete works, celebrating his fifty years of artistic labor, he was declared “one of the greatest painters in the history of Mexico and one of the few authentic world-wide greats of the present time.” The select minorities who witnessed the exhibition backed up that declaration as being no exaggeration.

When the papers announced the news of his death, the 25th of September 1957, the people, now en masse, put in an appearance before his remains. Multitudes invaded Bellas Artes where a funeral chapel was set up. Men of all ideologies and social position made the long trek from the center of town to the Dolores Cemetery, where he was buried in the Rotunda of Illustrious Men.

For three days, Diego Rivera owned the eight columns that newspapers reserve for sensational news. Columnists, editorialists and graphic artists paid him homage, praising his work. The same press that had hounded him now praised him unanimously. And Diego Rivera, the “dangerous Communist,” went to his grave covered by the national flag in the midst of the consternation of the whole country.

Rivera initiated the mural movement in our time, giving the work of art a public destiny since it is realized, not on the canvas of private collectors, but on the walls of buildings that are the property of the nation.

In 1922, he finished his first mural at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City with a philosophic theme he entitled The Creation. From that year to the year of his death, the measurement of the surfaces he painted comes to 30,000 square meters, an amount not realized by any other artist in the world.

The mural work represents the culmination of his experiences in the field of art, the maturity of his life, and the synthesis of the various schools of painting that he knew and mastered.

In his early youth, when he was a student at the San Carlos Academy, he quickly broke with the academic tradition and looked for the free expression of his ideas. He took up Spanish realism, was immensely moved by Cezanne, and managed to conquer, successively, the techniques of all modern tendencies: Impressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism, all of which he enriched with new contributions during his travels in Europe, especially in Paris, where he exhibited at the Salon des Independents and the famous Salon d’Autumne.

He had a surprising capacity for work; in 70 years of professional life he was able to finish several thousand pictures: watercolors, oils, ink drawings, pastels, pencil items, frescoes, etc., involving, all together, hundreds of millions of dollars in value.

When I asked him how many hours a day he spent at work he replied, “The time varies a lot, but almost always I go for the longest possible amount, generally from 10 to 14 hours a day.”

I was able to verify this affirmation seeing how in 1950 he started work on his fourth mural at the National Palace, representing a scene with the agricultural god Yacatecuhtli. He began on a Thursday at seven a.m. and he didn’t rest until nine o’clock the next morning, with the exception of a seven-hour break, after which he worked the night through until close to dawn Saturday.

Everything about Diego Rivera was monstrous: the way he worked, the way he’d insult, love and suffer. But his monstrousness originated deep down in the flame of his heart, the bottomless tenderness of genetic clay. He is comparable to Luther. The two come from downtrodden social classes, proud to be “sons of peasants.” Their fathers were both miners connected to the middle classes. Rivera and Luther are “energies erupting from the earth, like craters suddenly exploding,” according to the expression of Alfred Weber when referring to the father of the German Reformation.

Diego Rivera springs like a geyser out of the Mexican soil and starts to paint the way an Aztec god would do it in the days of human sacrifice, bloodied and filled with amazing vitality. D. H. Lawrence compared Rivera with the terrible Tezcatlipoca, solar and ecumenical deity of ancient Mexico.

In truth, we can identify this painter with each of the deities that form the Aztec pantheon: with Tlaloc, god of water; with Quetzalcoatl, beneficent god of light; with the profound Coatlicue, goddess of earth and death, portrayed with eagle claws and a skirt of snakes.

The writer Fernando Benítez tells how, after being up on a scaffold for three days working on the hands of a colossal figure, Diego Rivera fell to the ground and was taken home more dead than alive. Explaining this accident, his assistants said he had been pushed by the hands of the god he had just finished painting. Once, referring to pre-Hispanic idols he said, “They are my nourishment.”

One day, talking with him about his family, I learned that it had included “bandits, priests, military men and revolutionaries.” Diego Rivera was born on the 8th of December 1886, from that severe mix, at eight o’clock at night, in the mining town of Guanajuato, Pocitos Street number 8.

It’s necessary to look at the initial branches of his genealogy. His grandparents come from many places: Italy, Russia, Portugal, Holland, from Veracruz and San Miguel de Allende.

His paternal grandparents were Anastasio de la Rivera Sforza, an Italian Jew born in Russia from an unknown mother, and Inés d’Acosta, a Portuguese Jew who emigrated to Holland. His maternal grandparents were Juan Barrientos, originally from Alvarado, Veracruz, and Nemesia Rodríguez Valpuesta, from San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico. His parents were Diego Rivera, dead from cancer at age 75, and María Barrientos y Rodríguez Valpuesta, dead at 63, also from cancer.

Diego Rivera contains in his blood a cocktail of maps whose olive is Mexico. It should be imbibed slowly to avoid sudden intoxication.

As one of his critics has said, “He was born under the sign of events with contradictory symbolism: just as, in Mexico, General Porfirio Díaz reelects himself to a second term in office, in New York, the Statue of Liberty is inaugurated at the mouth of the Hudson.”

• • •

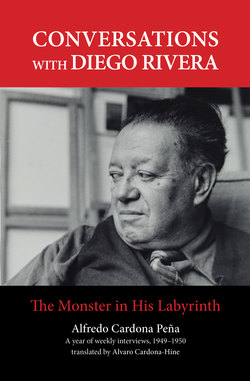

The artist was 63 years old when I began interviewing him. He was then a corpulent man, with a big belly, wearing huge pigskin shoes, overalls, coats of ordinary material and checkered wool shirts. He was careless in his attire but moved with delicacy and elegance, with a smile on his face that could pass for mockery, irony or sadness. He weighed more than 90 kilos, and he carried that weight high up scaffolds, working whole days without coming down, struggling like a demon.

His breakfast consisted of bananas, pears, apples and a cup of green tea while in the evening he’d eat the standard Mexican meal: noodle soup, meat stew and dessert. He opted for an oriental way of eating, and in his last years he went from using knives and forks to chopsticks. I always thought that in some recess of his being there was a hidden bonze or a lama who “hung up his Himalayas” and came to America, perhaps in a Viking ship.

Ramón Gómez de la Serna, in a much admired article about the master, said that when he showed up in Madrid, “he had the look of an authentic living Buddha, with the sumptuous fatness of the Buddha,” and that his eyes evoked “the awful look of one of his forebears.”

That is true. The first thing that impressed one about his face were those bulging eyes, ready to pop out of their orbits. From so much absorbing light and the colors of the world, those windows of the soul had been damaged a bit so when the morning would stream in, they’d redden and weep. These pathetic eyes seemed to swing free of their location and follow the attentive observer. In his self-portraits, Rivera emphasized their condition, which is why those faces he came up with are so tremendously intense.

His right eye was operated on in 1934 because of an atrophied ulcer caused by a streptococcus infection. The lachrymal gland in the upper section of the orbit was removed so that thereafter it was unable to retain any fluid; it would tear from time to time. After many hours working with the strong colors he preferred, that sick eye needed rest but the painter wouldn’t give in. It is no exaggeration to say that when Rivera painted he wept.

In his eyes the passion for art was stigmatized. It was only after he died that his eyes settled back to a normal position, shrouded now by the darkness they may have always yearned for.

Rivera detested cigarette smoke. He papered his studio with huge posters stating the familiar “No Smoking, Please.” He worked in the midst of great shafts of light, and when it was artificial it was so strong as to be blinding when one first entered the room.

We shall always remember those “bug eyes, held back by bloated, salient lids like those of a batrachian,” as Frida Kahlo used to say.

• • •

In 1949, the Mexican president opened the Diego Rivera exposition at the Museum of Plastic Arts at the Palace of Bellas Artes to commemorate fifty years of Rivera’s work. Hundreds of works were shown on that occasion, starting with his first drawing, (The Railroad, 1889) made at age three, and ending with photographs of his last murals from the National Palace.

Diego Rivera was revealed to his people, unfamiliar as yet with him, as a true master of all historical styles of art. Ignorant men, who are legion, used to call him “a nobody.” One of them, a boorish gentleman, decided one Sunday to visit the much talked about exposition and was struck dumb. He understood nothing, of course, but underwent a shift of consciousness. He had to take off his hat before an artist so often maligned.

• • •

When it comes to technical matters, we shall refer only to his experiments and research into wax painting, better known as encaustic painting, whose most notable exponent was Delacroix (Lateral chapels of the Church of Saint Sulpice in Paris).

Rivera himself, following the exposition, discussed his own research into encaustic and al fresco techniques with the Mexican painter Juan O’Gorman. Here is the crux of the matter, revealing of the scientific and humanistic fervor of the artist: “I began to get interested,” he told his friend, “with wax and resin color around 1905, above all with the idea of substituting it for oil color, as Raphael did. In those days that was the novelty and excitement among painters working with the neo-impressionist tendencies, like the great Seurat and the Swiss-Italian Segantini. Nobody had found the procedure to cauterize and arrive at the proper encaustic means. So I resolved to go to the sources, which were Greek, Coptic, Egyptian and Roman, but these kept the secret of such painting a mystery. And so it was. There was nothing else to do but take recourse in Pliny’s writings on natural history. There is one chapter where he talks of painting methods. Montavert, Delacroix and others had consulted Pliny without success so I, with the audacity of one who knows nothing and lacks respect for classic authors, thought it might be a question of how to interpret the Latin text, and went to look for it at the National Library in Paris. Montavert said that Pliny mentioned encaustic as ‘an oil of pine and stone.’ Of course, nobody understood what that was all about. When I came upon that specific passage in Pliny I could hardly believe what I was reading. The key word was petroleum. Petroleum in Pliny’s time could only be obtained through exudation or in natural springs. What Pliny meant was really ‘hide,’ which Montavert had translated as ‘pine.’

“Then I remembered that in the Caucasus and Asia Minor, way before Pliny, petroleum was obtained by placing the hide of lambs on fields exuding petroleum. But there was another issue pending, the most important: how to cauterize it. About this Pliny said ‘For fine work, painters use the torches of gold and silversmiths.’ That reminded me of the silversmiths of my childhood in Mexico, how they used a lamp loaded with petroleum, blowing into its flame with a metal blowgun and sending it to a base of clay where the metal they wanted to melt lay. In other words, the mysterious torch that confused Leonardo da Vinci was nothing other than a common lead blowgun. I tried this approach over ground colors in an emulsion of copal oil and wax dissolved in an essence of petroleum and was able to obtain the result used by the old masters, reincorporating the encaustic procedure into modern art.”

What about the aesthetics of his painting? Let us hear what the philosopher Samuel Ramos has to say:

“Diego Rivera’s aesthetic begins with the assumption that art must be the expression of an ideological content determined by the social conditions of the moment in which the artist lives. The notion of art for art’s sake is, for Rivera, a mask hiding the pursuit of interests other than artistic. The political basis he has given his work blinds his opponents, keeping them from seeing and judging its plastic values. As a human being, Diego Rivera has involved himself in the social struggles of our time; he has actively joined leftist causes. His painting involves a political thesis. His entire mural achievement is the visual objectification of a socialist idea based on Mexican history. It is not proper to discuss his political notions when considering Diego Rivera’s painting. What can be discussed is whether the procedure of using painting as the instrument of an ideological expression can be legitimized from an aesthetic point of view.

“If someone looks into Rivera’s work for the ideal of beauty as formulated at a certain period of European art, which has been turned into a kind of universal model, that person is wasting his time. It seems to me that the true universal conscience of art ought to be one that denies the right to grant privileges to a specific form of beauty at the expense of others, recognizing the existence of multiple forms through which different epochs, different peoples and diverse individuals, have found that same spiritual pleasure that confers unity to the perception of what we call beauty. What distinguishes Rivera’s painting from its European counterpart is precisely an original manner of seeing and grouping the diverse plastic elements provided by a reality as peculiar as that of the Mexican people, heretofore unknown in the world of art. Its aesthetic value is realized by the authenticity with which the painter has known how to capture the personal features of his people and his environment, as well as by the fidelity of the artist to his own manner of seeing and thinking.”

Relating to the initial influences on Rivera, his spiritual connection to the great masters and the discovery of his own world, let us see what Germaine Wenziner has to say:

“No sooner had he arrived in Europe than he visited the museums, diving into Assyrian and archaic Greek art. He stopped in front of the blues of Fray Angelico, wandering long among the primitives. He leaped into the sobriety of Courbet, yet surrendered more deeply to the charm of the Moulin de la Galette, was unsettled by the musical structures that Renoir had created between the palpitating life in his drawings and his vibrant chromatics. Every art manifestation shook him. He suffered the authoritarian presence of David’s portraits, returned to the impressionists, the neo-impressionists. Afterwards, discovering Seurat, he thought he’d go crazy. Nevertheless, it was Cézanne who made the deepest impression. What affects one the most in studying the life of Diego Rivera during that period is his extraordinary expenditure of energy and the excitement in this foreign painter ready to discover everything that the pictorial universe could be hiding. His genius was like a demon punishing him without respite.”

Crespo de la Serna lists some key moments when Rivera found his creative conscience. Certainly his encounter with the work of Cézanne at the boutique of Ambroise Vollard, “an impact that in spite of his flight to other artistic premises and his devotion to El Greco, left an important mark on his spirit and even more on the on-going gestation of his art.” His dealings with Cubism “in which he managed to attain a clear presence and which he later transformed into a constructivist system based on previous experiences.” His visit to Italy (frescoes from the Renaissance, the work of the primitives, etc.) “from which he derived his resolve to paint murals in the future.” Lastly, “his re-discovery of the Mexico intuited in his childhood and adolescence, when he returned to his country for the second time in 1921.”

After his cubist period, Rivera left Paris a mature artist.

“Fifteen years away from his homeland,” says Wenziner, “had made him a more absolute Mexican than he had ever been. Like Flaubert, who, during a trip, conceived Madame Bovary as a type of woman different from those of other places, in the same way Diego Rivera, during his stay in Paris, meditated and conceived his great Mexican masterpieces.”

This re-discovery of Mexico gave the painter a unique originality, thanks to which he reached the stage of a definitive awareness as an artist, painting his land with a chromatic and incomparable force. So, this entire process, all this evolution from his beginnings to the time of his major conceptions, was presented in the exposition of 1949, the supreme triumph of his life in front of his people. He actually filled all the salons of the Palace of Bellas Artes. The amazed public went from one period to the next, confirming silently the total revelation of his genius. Afterwards…afterwards came what we may call an evening with the sun on the horizon. Rivera gave himself up to painting with the fury of the possessed, just painting, painting. He painted at all hours of the day and night, at home, in his studio, in the street, in villages. He continued the frescos at the Palacio Nacional, developed projects, scenographies, jottings…you name it! It was like an antediluvian waterfall, that enormous fountain that emerges from the cracks of creation, a mastodontism of paint.

Suddenly, the giant swayed. The logical breakdown arrived, the first cancerous manifestations. He said nothing, just went on working. Nevertheless, he made a trip to the Soviet Union, seeking a cure. In the USSR he was overwhelmed by tributes and brought back with him a new exposition, which he exhibited successfully in his own home. He declared that he had been cured and that he had never felt better. On December 8, 1956, he celebrated his seventieth birthday, and his admirers proclaimed him “the greatest genius in contemporary plastic art.” There was a popular gathering in front of his “Pedregal Pyramid” [the place where he lived and worked, —Tran.], and people brought flowers and song. Children, old folks, workers, professionals from all disciplines, came to congratulate him. In the middle of the twentieth century, people climbed up and down the stone steps of that imitation of an Aztec temple. It was exciting. It looked as if all the demiurges of the Mexican Valley had made a date to meet at that place. The museum-pyramid of Rivera, located in the Pedregal of San Pablo Tlepetlapa, is a monumental structure of vast proportions, an actual materialization of Rivera’s spirit. The ground floor is dark; one wanders through it as in restless dreams, those dreams that tell us things we can’t remember but feel afterwards. The palaces of the princes of the Anahuac must have been like this, colossal, depressing, full of a threatening, rocky solidity. But as one goes up to the floors above, one receives the consolation of light and, witnessing the smiling landscape, a confrontation with limitless beauty.

Everywhere, from corbels and niches craftily located, the visitor is faced by the horrendous visages of ancient deities. One touches with one’s eyes the huge past in a magical act of extreme simplicity.

Today that sumptuous tomb, that Mexican Gizeh is empty, as if without substance. It contains more than 40,000 sculptures, but it is missing its key treasure: the body of Diego Rivera. It is a castle without ghosts, a legend without the dead; something unimaginable because it doesn’t project a shadow. But the day will come when, from the Rotunda of Illustrious Men (where municipal pride deposited his remains) the great artist will be moved to the atrium where he definitely belongs by his own right. The residential neighborhood of the illustrious has residents like Amado Nervo, and complications could arise. On the other hand, in the pyramid of Tlepetapa, the remains of Rivera could rest beside his beloved shadows.

• • •

On the 12th of August, 1949, I headed for the Villa of San Angelín, a few kilometers from Mexico City, where Diego had his studio. The object was to interview him on the basis of his Exposition at the Palace of Bellas Artes.

I lost most of the day. Rivera showed up late and had to deal with several people who had arrived before me. Most were tourists, the kind that touch his hands and prove to themselves that geniuses still exist.

I wanted to talk with him face to face, to observe him and obtain a private sense of his personality. I hadn’t made any concrete plans, not even formulated a special set of questions since experience had taught me that an initial contact involving a spontaneous chat can yield the most faithful impression of an individual.

On the way to San Angelín it occurred to me to ask Rivera the simplest things, the most humble, that which being known is ignored. Like, “What is a painter?” “What is a painting?” and “How do you make a mural?” It hadn’t occurred to anyone, facing Rivera, to technically take advantage of that childish restlessness when a child arrives at that tremendous age of “why this, why that.”

“Father, what is a car?” “What are trees made of?”

Really, the matter was settled. I would interview Rivera about the most fascinating issues of the craft with the greatest simplicity. I would face the monster in his own labyrinth and stretching my hand past the bars of his intimacy, ask him for the facts of his life.

On the way there, I decided to wander about a while around his castle, that Aztec castle where one feels and senses the palpitating heart of the past. The studio-home of Rivera, intact at this date, is different from the other buildings in the area. To the right are the servants’ quarters, and to the left the three-story studio connected to the main building by a cement bridge. On the top floor is a workroom reached by an outdoor stairway. In front, making do as a barrier, is a row of cacti, the representative plant of Mexico.

Rivera’s studio presented the typical disorder of an artist’s dwelling, but all working materials were in their place, most carefully guarded by Manuel, his faithful servant.

In a corner of the room one could see a shelf with pre-Hispanic sculptures, but the best of the priceless, 30,000-piece collection was on the first floor, from where they were transported to the pyramid at the Pedregal, where he planned to be interred with his treasures, like the famous pharaohs of Thebes.

For years, Rivera invested large amounts of money collecting pre-Hispanic pieces and he had at his service an army of Indians in charge of finding him monoliths or Aztec deities from anywhere in the republic. He was the most conspicuous visitor of tombs in America; his nails were black with earth thousands of years old.

The study had little furniture, but in his private rooms he had an astonishing collection of highly colorful silk shawls, which he used on his models when he was ready to paint them. Also to be found there were stuffed birds, Andean and Tibetan caps, stone pipes, and musical instruments. But the things that caught a visitor’s attention the most were the Judases, colossal dolls made from cardboard and sticks created by anonymous artists, to be burned after Easter. Among these figures were also devils to be found; and Death herself, the perennial beloved of the Mexican people, who used to adorn pre-Hispanic temples thousands of years ago. Rivera loved these products of popular art passionately.

In this room we are describing, so well protected from street noises, the painter would work twelve to fourteen hours daily. There he painted naked women, African blacks, famous artists, indigents and beggars. Clara Bow and Paulette Goddard posed there for hours. The man who was then Treasury Minister, Ramón Beteta, the Canadian poet Phileas Lalane, Mrs. Rubenstein, the Mexican movie star María Féliz, they all sacrificed whole days of immobility just to be painted by Rivera. No one forgets to this day the scandal provoked by the painting of the poet Guadalupe Amor, of Mexico City, when she appeared on canvas totally naked in a local gallery.

When the artist was at work, only people he trusted could gain entrance to his inner sanctum. He would admonish his servants severely if they allowed someone in not previously announced, or anyone he didn’t know. I saw government functionaries, professors and American students waiting for hours without being received by the San Angelín dictator.

At eight p.m. the night of August 12, a slow, heavy-set, parsimonious Diego came in to where I was, speaking his Guanajuato version of English and kissing women’s hands. I was able to explain my idea to him and he was immediately interested. He invited me into his studio, and while taking off his jacket, said, “Ask me…”

And I asked one, two, twenty…I don’t know how many questions ‘til the small hours of the night, with him answering from memory, with an incredible accuracy, without pausing, without worrying much about what he might be saying, all of it spilling out in an unconscious and magical manner.

Since the material I obtained was so abundant, the next day I decided to divide the interview into three parts for the newspaper El Nacional, where I was a collaborator. I was finishing the third and last part, when the Satan of journalists tempted me. Rivera was able to talk without respite for weeks and weeks on end on life issues, his art, the violent and passionate world in which he lived. Why not take advantage of that mental machine, so full of delicious sound bites, beautiful, human, including contradictory notions of atheism and ferocity? Darkness and lightning bolts inhabited his soul, larger than life passions, thick as jungle vines, tenderness, unconformities and revelations. All that besides his work, his gigantic achievements…. Wasn’t this divine liar one of the most interesting artists on the continent, not to mention the many scandals accompanying what he did? Didn’t he practice the art of lying in an exquisite manner never heard of before? Weren’t his cape and sword scandal itself, his political radicalism and his demon the flame of the savage past? All of this meant that I had to arm myself with patience.

I got in touch with him by phone, telling him that I wanted to continue our chats, and he agreed. He was delighted to accept, of course, because now he’d have a loudspeaker to propagate his views, unburden himself, criticize, theorize, and unwrap before a sharp mirror his life as an artist, so intense and vital that today, even as a dweller of the night, he casts no shadow.

This is the way my newspaperman’s task began, one I thought would last one day and ended up taking fifty-two weeks; each Sunday for a whole year. El Nacional kept publishing everything and when Rivera was out of town I’d make the interview up, at my own risk, talking at him.

I wrote the articles at all hours, in different places and ways: in cabarets, at my desk, in busses, up on scaffoldings, in private cars and taxis, using pencils, pens, typewriters, telephones and television. Rivera would dictate without moderation, vertiginously, without pausing, sometimes without breathing. Other times he’d dictate reluctantly. My job at such a time was limited to placing my hands on a little table without nails and invoking the spirit. The table would move and I would interpret its movements. The development of the talks was my own, all questions were my inspiration. I’d present him with specious questions to trip him up and have him reveal some invaluable confidence. But I would do it with respect for his person and admiration for his genius.

All this with the joyful anticipation of someone beneath an apple tree, waiting for the fruit to fall in bunches, for whole sentences would come from his mouth one after the other, and I would have to grab them as they went by. What a way to speak! Without the least sense of what a limit might be, or a pause. He loved his notions and would speak like a deranged orator, like a medium, like an oppressive loudspeaker spewing its propaganda. But what a difference between a logomaniac without sense and this precious disorder of the aesthetic lover, of a Rivera presenting himself! I had to write down his words with idiomatic mendacity, jotting down theories, observations, and the names of foreign personages and artists whose correct spelling would cause endless problems. When transcribing my notes I would be in serious trouble until I could take refuge in encyclopedias and reference books.

Rivera appears in my texts like a storm of leaves.

Every word in this book is a footprint of his enormous vocal leaps, footprints he pressed against my ears like someone stepping on wet cement. I have gathered them, heavy, rough, poorly schooled and profound, the footprints of a fat man who doesn’t equivocate. The soles of his shoes had nails but I never saw myself as a rug. I have respected the raging of this centaur ready for a fight, the invectives out of place, his venting, the tremendous guffaw of his irony. Had I suppressed those aspects, ignitions of his nature, I’d be presenting a false Rivera, a Rivera subject to the conventional. That would be a crime against fidelity.

Nor have I had to rearrange the style too much, convinced that the task of an interview is to retain the energy of a conversation. These pages obey the speed of lips, so to speak, with the need to finish before a deadline. Perhaps the paragraphs filling these pages capture eternal moments, sketching his temperament more accurately than careful and overworked treatments.

Many people will like this basic way of presenting Diego Rivera, but others will inevitably feel the words of the artist as a sudden sting, like the hives produced by certain shellfish. I am sure they will feel a need to refuse the violence used, a desire to argue with his notions directly. Unfortunately, Rivera is incapable of replying personally. Only his work remains, and in it, forever shining, is the testimony of his human truth.