Читать книгу Becoming Dr. Q - Alfredo Quinones-Hinojosa - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TWO Faraway

ОглавлениеMisfortune seeped into my family’s existence very slowly at first, almost imperceptibly. Then, toward the end of 1977, when I was nine years old and in the fifth grade, tough times seemed to descend on our household all at once, like a drastic shift in the weather. Even through the foggy lens of memory, I can recall the moment when I understood that we had left behind the simpler, more secure days and were treading upon shaky ground.

The moment of realization arrived when I found my father behind our house, alone, crying desperately. Something was very wrong. My first reaction was to ask Papá why he was crying. But I was too shocked to ask. Here was my father—the strong, stubborn head of our family, highly intelligent though not educated, hardworking, honest, and kindhearted, the colorful, passionate, larger-than-life man who was my hero—crying his eyes out.

For some time, there had been clues that business at the gas station was going poorly, but not until I found him crying did I understand the magnitude of the crisis. Without being told exactly, I figured out that the worst-case scenario for our family—losing the gas station, our primary livelihood and means of putting food on the table—had occurred. The station was our family’s identity—not just where I’d worked since the age of five but a place of business that gave us stature in the community. Even at nine years old, I understood why this loss was such a blow to my father’s sense of self, not the least because his father, Tata Juan, had chosen him to be his partner and then given him this endowment that was to have secured our future well-being.

In the year that followed, I came to better understand the circumstances that had led to this predicament. One factor was the financial downturn in Mexico, which would continue for several years and become a widespread economic depression. Before, we had steadily worked our way up and into the lower middle class. But without the gas station, we tumbled so far from that rung that we had to struggle to obtain the bare necessities—including the money needed to feed a growing family.

This descent was a shock to our system, as it was for much of the country, which had been enjoying relative prosperity and improvement since the 1930s, when American companies and other foreign investors had come in to develop rural areas and outposts like Palaco. The influx of outside investment created jobs and helped lift many families out of poverty. But in many cases when the companies left (or were forced to do so when the laws in Mexico changed to limit foreign-owned business), so did jobs and family security. The middle class sank to lower levels, and the poor became the really poor.

The other factor that contributed to the loss of the gas station only came to light after my father had to sell it for next to no profit. To do so, he had to first turn it over to his brother, my uncle Jesus, in whose name the government had originally issued the PEMEX (Petroleos Mexicanos) permit and who had wisely renewed it over the years—to his credit, since few such permits were available anymore. When Uncle Jesus tried to turn the gas station over to new management, a survey of the property revealed a startling fact. All those years, unbeknownst to Papá, there had been holes in the gas tanks and they had been steadily leaking their contents into the ground. So much gas from the underground tanks had seeped out that everyone’s first reaction was to thank God that no stray lit match or mechanical explosion had ignited an inferno that would surely have swallowed all of us up. During all the years in which we had lived in the apartment at the back of the gas station, we had been unaware that such a horrific event—of a type that was all too common in our area—could have occurred and ended our lives.

Why had it taken so long to realize we were paying more for the gasoline than we were selling at the pumps? It should have been more obvious that the profits were literally leaking away into the earth under our feet.

Papá may have had distractions that kept him from noticing our sinking bottom line. And he was young and inexperienced, never having had the chance to explore the world before settling down, instead going from marriage at the age of twenty to becoming the father of six children within ten years. My father might have been fighting depression, which became more evident as our financial status worsened and as alcohol became a more frequent means of escape, a way to self-medicate.

Looking back, as I try to understand what my father went through, I truly believe that he was destined for great things, as my grandfather had foreseen. But Papá wasn’t on steady ground when sudden misfortune capsized him, so finding his way to terra firma became that much harder. Losing the gas station also represented a decline in our standing in the Quiñones family and in the community—even though my aunts and uncles, as well as my paternal grandparents, maintained a policy of denial about how much trouble we were in. Still, despite our attempts to keep up appearances, they must have known of our struggles.

But within our household, the reality couldn’t be ignored. It is hard to be in denial when your stomach is empty. One scene is burned into my memory: my mother standing over the stove making tortillas, just flour and water and a touch of oil in the pan to feed us children—me at ten years old, Gabriel at almost nine, seven-year-old Rosa, Jorge at about four years old, and baby Jaqueline not yet six months, then asleep for her nap. There we sat at the table, hands folded, waiting quietly to split the tortillas as they came from the pan. Decades later, I can still conjure the smell that told us how delicious every morsel was going to taste. Remembering that near silence in the kitchen, I can still hear the music of the tortilla sizzling in the oil—the most hopeful sound in the world at that time. To this day, the mere mention of the word “hunger” summons that scene to my mind.

That was dinner—flour tortillas with homemade salsa. Gone were the days of eating meat once a week. Gone were the nights of imagining that my father was out somewhere picking up bread or something hearty for our breakfast. Gone were Christmas mornings waking to the smell of my mother’s tamales. Now, as I lay on the roof, instead of looking up at the sky and dreaming of traveling beyond the stars, I dreamt of more practical desires—a piece of pan dulce and a time when we would have beans and potatoes at our table again.

Every now and then, I dreamt of things that I’d like to do or own for myself that weren’t food or family related—like the time I became very focused on owning a pair of Ray-Ban sunglasses. Back then, they were the essence of living la vida loca!

Strangely, it was in this darker period that the nightmares that had plagued me for most of childhood suddenly ceased. Now actual threats to our security occupied my waking thoughts. But instead of feeling helpless, as I sat up on the roof late into the night, I was emboldened by thinking of ways to help. Surely real problems could be met with real solutions.

I was also convinced, as I told Mamá, that the many hours spent in church, as an altar boy and in confession, could be better spent working to help the family. Besides, sitting in church was boring and my attention span was not my strong suit. My mother thought for a moment and then pronounced her decision. “Alfredo, if you continue as you are until your First Communion, after that, it will be up to you to choose whether or not to attend church anymore.”

She had only two conditions: first, I must remain observant and good during Easter week every year; and second, before taking First Communion, I would have to go on my knees from outside of the church into the sanctuary, confessing my sins as I crawled all the way to the altar.

Now I had a tough decision to make. Easter was actually a dark, somber holiday in my estimation. The rituals were strange to me, unlike those of my favorite celebration, Día de los Muertos—the Day of the Dead—when we ate candy, danced, and dressed up in skeleton costumes and skull masks, giving death its respect but mocking its finality. Still, if these gestures meant that much to my mother and I only had to go to church one day a year, this wasn’t a bad deal. The real challenge would be coming clean, in public, about my many misdeeds.

And yet, at ten years old, that’s just what I did. On that long crawl, as I shuffled on my knees up the steps and down the aisle on the cold, hard, marble floor, I asked to be forgiven not just for the past but for future wrongdoing as well. These sins of mine were not generic or abstract; they weren’t extreme, but they weren’t inconsequential. They included the little pyrotechnic experiments I had conducted in the fields with my investigative team in tow, as we created geysers of flame high in the air. As I had admitted to our priest in previous confession, I also had a habit of not telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth when interrogated by my elders. Though I didn’t lie outright, I had found a way of avoiding the truth by saying nothing—like the time when I was seven or eight years old and my father questioned me about a particular boast that I had made to the older boys out in the schoolyard.

Rather than asking me if it was true that I had bragged that I was so fast I could run around and pull up girls’ dresses without their realizing it, my father asked, “Are you behaving yourself at school?”

I was outraged. “Of course!” This was true when discussing my behavior in the classroom, where I was an angel. Out in the yard, a little devil got the better of me.

“Tell me the truth, Alfredo, were you trying to look up girls’ dresses?”

“What?” I put on a disgusted, shocked look. Very convincing, I thought. “Who said I did that?”

“Never mind. I’m asking if you did or didn’t. Well?”

“And I’m saying that is a terrible accusation, and whoever made it must not have known what they were talking about!”

We could go on like this for hours. As long as I wasn’t caught in the act, I figured, I couldn’t be convicted. But I knew deep down that my action counted as a sin by omission and confessed to the priest soon afterward. The priest seemed more upset that I had looked up girls’ dresses than that I had lied. Clearly, I wasn’t living up to the moral standards of the church or showing the kind of character that honored my family and my parents’ values.

While crawling on my knees from outside the church, I expressed true remorse again for that episode. And there was more. Besides having a sharp tongue and sometimes lashing out with sarcastic comebacks, I had been known to tell a dirty joke or two. Or three.

For these sins and more, I asked forgiveness all the way to the altar. Even though I had no reason to feel responsible for the loss of the gas station, just in case, I begged for forgiveness if anything that I had done or not done had contributed to our misfortune. More important, I also asked to be given the responsibility and the strength to help relieve the problems, along with the understanding to make sense of what was happening to us.

Thus ended my relationship with organized religion. From then on, though I attended church occasionally, I communed with God wherever and whenever I chose: at night under the stars or on my walk to and from school or to various jobs. There were times when my one-on-ones with God led to some heated questioning: why was there so much suffering, how could a merciful Supreme Being allow poverty, illness, injustice, and misfortune to exist, and what had my innocent baby sister Maricela done to be taken from the world? The explanations were rather hazy, although my faith that I would one day come to understand these mysteries was not.

In the meantime, my source of inspiration in coping with our earthly difficulties was my mother. Unafraid, without complaint, Mamá made up her mind that she was going to hold her family together, in spite of the already strained relationship between my parents and even with our ongoing challenges that had no easy remedy.

Already resourceful, Flavia now expanded her activities. In addition to buying and finding used goods to refurbish and sell, she soon set up a little secondhand shop in a market area outside Palaco. Forty miles south of the border fence that ran between Mexicali on the Mexican side and Calexico on the U.S. side, her shop attracted both local customers and tourists who wanted to venture into the country but not too far. When Mamá had raised a bit of capital, she bought an old sewing machine with a foot pedal and began doing piecework at home at night for a costume company—sewing, of all things, sexy outfits for hookers at the local brothel!

Word of this particular work spread in the neighborhood, and I was not amused when the taunts started. Too bad for the kid who sneered at me one day, “What’s it like to be the son of a woman who makes clothes for prostitutes?”

Putting my sharp tongue to use, I responded, “What’s it like to be the son of the woman she’s making the clothes for?”

After getting my butt kicked badly for that remark, I resolved to fight less and to find a better way to harness my outgoing personality. With help from my Uncle Abel, one of my mother’s brothers—and money from trading in all the marbles I’d been amassing for years—I went into the hot dog business. Who could resist a child with a big voice, standing up on a stool and hawking hot dogs? No one, I thought! Unfortunately, few could afford my wares. I then started selling roasted corn, but as the national economy worsened, I didn’t fare any better.

Desperation set in. Just when things became really bleak, my mother’s oldest brother, Uncle Jose, began to make periodic deliveries from the United States, where he worked and lived part-time—bringing food staples and sometimes money that meant we could eat for the next few months. The sight of his pickup truck heading our way and kicking up dust on the road—loaded with burlap bags of beans, rice, and potatoes—was like witnessing the arrival of the cavalry in old Western movies. Just in the nick of time!

I didn’t know the extent of Uncle Jose’s generosity at the time—he had few resources himself—but I did know that he cared enough to help. Interestingly, no one ever told Uncle Jose how bad things had gotten for us. Somehow he figured it out.

No one else did, including my mother’s brother, Fausto, who came down from the United States to visit us every Christmas, bringing my cousins, Fausto Jr. and Oscar, with him. Uncle Fausto had gone to California as a migrant worker in the 1950s through seasonal passports provided by the Bracero Program. Thanks to his tenacity and ability, he had found permanent work as a top foreman at a huge ranch in the town of Mendota in the San Joaquin Valley, where he was raising his two sons as a divorced father.

A plainspoken man, Uncle Fausto would have said something about our deteriorating circumstances if he had picked up on them. Instead, my mother had to raise the issue and ask him about the possibility of going to the United States for a summer of migrant work. When Mamá first brought up the idea to my father, he didn’t protest, although I imagine he wasn’t happy about the prospect of having to go across the border to America and pick cotton and tomatoes. But since he didn’t have any better ideas, my mother decided to talk to Uncle Fausto during his annual Christmas visit.

This decision came after months of tension at our house. Nobody said anything about it to us children, but the look on my mother’s face when my father came home in the middle of the night spoke volumes. Papá never laid a hand on Mamá, but he had a bellowing voice, and when the two of them began arguing, the sound of his unhappiness filled our house, making me feel that I couldn’t breathe, much less stop their arguing. One day, when Gabriel and I were in the background during a heated exchange, Rosa got caught in the crossfire. She stood between my parents, crying and begging them to stop yelling at each other, to little avail.

Mamá knew that we couldn’t go on as we were. But when she spoke to Uncle Fausto, her tone was casual, as she reminded him that we all had the required paperwork to travel back and forth across the border for tourism, so we wouldn’t need any new or special documentation. The plan, my mother suggested, was that she and my father could work, and we children could enjoy a summer holiday.

“Let me see what I can do,” Uncle Fausto replied with a shrug.

Not too much later, we learned that everything was in place for the summer and that when school let out, we were going to Mendota for two months. Road trip!

I couldn’t wait. My American adventure was about to begin.

Mendota, California, bills itself as the cantaloupe capital of the world—a distinction that made me feel right at home, since I came from melon country. But something else also lent familiarity to our journey, literally providing a link to my backyard at home. Mendota had been founded by the Southern Pacific Railroad in the late 1800s as a switching station and storage area for repairing and housing railroad cars, and most of the products of California agriculture were unloaded and reloaded here. What were the odds? The tracks that passed by Mendota originated at the Port of Stockton (where I would eventually work)—where the ships docked to unload their cargo onto railcars at the water’s edge. After Mendota, destinations could be switched eastward or westward, or the trains would continue south to the end of the line in, yes, Palaco!

None of the dots had yet connected for me back in 1979 when I was eleven years old. But I had a feeling of destiny about that summer. As my first exposure to the United States, Mendota was as close to paradise as I could imagine—a Garden of Eden about forty miles west of Fresno in the middle of the fertile San Joaquin Valley that stretches for miles from Stockton down through the middle of the state, almost to Bakersfield.

As much as a quarter of the produce grown in America comes from California, and most of it is grown in the San Joaquin Valley. As soon as we arrived at the ranch where Uncle Fausto was a foreman, I reveled in the freedom of the first real vacation I could remember. And we could eat for free! I looked out upon field after field, as far as I could see, rich with abundant growth and produce of every variety. All around me were rolling hills, wooded glens, irrigation canals, and winding dirt paths, all begging to be explored. Plus, my cousins Fausto and Oscar were always ready to join me and my siblings in the fun.

Every morning, after the adults left for the fields, the main goal for the day was to figure out how to get to a magical place we called “Faraway.” You would only know you had arrived there when you got there! If I needed a break from our escapades, I hung out at the garage where tractors and farm equipment were serviced, offering my mechanical know how and skill in maneuvering large vehicles. I also started a business cleaning workers’ rooms at a nearby barracks. Because my rates were lower than the competition’s, I was in demand.

Unfortunately, the competition, a fifteen-year-old, came after me with his posse. One of the guys pinned me down and twisted my arm so painfully that I couldn’t use it to clean. Clearly, the time had come to learn some real Kaliman maneuvers for self-defense.

Thus, when we returned home to Mexico, my first thought was to take boxing lessons at a gym in Mexicali. But after sadly saying good-bye to the paradise of Faraway/Mendota, our family was soon stretched as thin as ever, and I accepted that I would have to create my own self-improvement program. So I came up with a bold plan to turn the out-of-doors into an obstacle course for my self-designed training regimen. Aha! On my way to school or work, I’d race against my previous pace, pushing myself faster each day, sometimes inventing athletic moves that called for leaping over creeks, catapulting over fences—anything to squeeze out another ounce of energy.

Such was the Kaliman approach. According to the comic-book hero’s history, his DNA was not superhuman. He had simply pushed his human abilities to their optimal levels, training himself to be as strong as fifty men, to levitate and practice telepathy and ESP, and to fight evil and injustice without ever taking a life. Except for his occasional use of sedative darts to temporarily paralyze evildoers and a dagger employed only as a tool, he needed no weapons to overcome an adversary. Kaliman would even risk his own life to avoid causing the death of another human being. Dressed all in white except for the jewel-encrusted letter “K” on his turban, he was also a scientist, often spouting interesting facts about nature and the cosmos while embracing the attainment of knowledge with such philosophies as “He who masters the mind masters everything.”

Fortunately, school still provided a positive place for me to work on mental mastery, even though being the youngest student and the teacher’s pet brought problems. These concerns intensified when I changed schools and no longer had my circle of protectors. Worse, there were some seriously scary kids at the school. One of them, Mauricio, a mountain of muscle, did back flips and propelled off walls like a circus acrobat, and the ground shook whenever he walked by. The only person who wasn’t afraid of him was his sidekick—known as El Gallo because he crowed like a rooster when he was triumphing over anyone who made the mistake of tangling with him. The Rooster was one of the tallest thirteen-year-olds I had ever seen, with long, sinewy arms designed for landing jabs and uppercuts. Of all the kids I was determined to avoid as part of my survival, these two were at the top of the list. Guess what? Just my luck, Mauricio was in my natural science class, sitting right behind me and peering over my shoulder to copy off my tests.

I saw only one solution and that was to offer him and his fellow bad boys my tutoring services. We settled on a fee, in addition to a promise that they would provide protection from any of the bigger bullies. As I explained, they were on my payroll.

The tutoring sessions were not as transformational for my pupils as I had hoped. Their understanding of the fundamentals improved, but I soon concluded that the more expedient (and profitable) path was to let them copy my answers on my tests. Of course, I knew that this solution was wrong, and I didn’t pretend otherwise. But on an up note, the school saw a downturn in troublemaking during this time.

With tutoring and restaurant work, I could contribute to our family’s welfare without falling behind in my studies. However, I soon began to lament that I couldn’t pursue much of a social life outside of school. At fourteen, I had experienced my share of flirtations with girls in my class, but I had not had the money or time to explore romance. No dates, no dances, no strolls down the sidewalk holding hands. Did I feel sorry for myself? No, I couldn’t allow that. But working every waking hour outside of school, day in and day out, was definitely getting old.

I finally confessed these feelings to my mother, trying to explain for the millionth time why, at the age of fourteen, I believed that the time had come for me to return to Mendota for the summer, on my own. If I could work there for two months, I could help the family so much more than if I stayed in Mexico. Moreover, I could put money away so that I wouldn’t have to work full-time during the school year.

This would also allow me to move more rapidly in completing the special training program I’d recently begun that was the equivalent of a college curriculum for those studying to become teachers. Mamá and Papá agreed that becoming an educator was an excellent choice for me: not only was it a respected profession, but it would enable me to start earning a living in a shorter amount of time than, say, studying to become a lawyer or a doctor. And, in the best of all worlds, if I became a teacher, I could afford to continue my education toward those other professions if I desired.

Although I didn’t have a work permit for my summer plans, that hurdle could be overcome with the passports that let us go back and forth across the border. Nothing anyone could say was going to convince me that this survival strategy was not a good idea; it was the only idea. Mamá finally gave in and went to the phone booth to call Uncle Fausto.

“Absolutely not,” was his firm response when she asked if I could return to Mendota and work the fields for the summer. However, he quickly added that he would love for me to come for a vacation.

Grateful for his offer, I was determined to change his mind. During the entire ride up to Central California, as I sat quietly in the passenger seat of a car driven by a relative who was heading that way, I pondered how to convince Uncle Fausto to give me a shot at proving myself. When I was finally dropped off in front of my uncle’s house, I stood there with my few items under my arm and gathered my resolve, not sure that anything I could say would sway him. At 102 pounds, much skinnier than when my Mendota relatives had last seen me, I could tell that Uncle Fausto and my cousins were shocked when they came out to welcome me. Uncle Fausto’s first words were, “Are you hungry?”

Before I could answer, an ice cream truck playing cheerful organ-grinder music came down the road with a throng of dancing children following behind. Uncle Fausto gestured toward the truck and asked, “Want an ice cream?” Thanking him profusely, I had the pleasure of trying my first-ever rainbow-colored, push-up sherbet. Savoring its creamy, sweet deliciousness, I was in heaven. And it was a mere morsel compared to the hearty dinner that Uncle Fausto set out that evening. I realized that I could easily forget about working and just enjoy the good life for the next two months. Yet no sooner did that thought occur to me than an image arose of my family back in Mexico, sitting around the table each night and subsisting on the most meager diet.

That evening I began my campaign with Uncle Fausto, telling him what an asset I would be in the fields. Again, he forcefully refused. But after a lengthy back and forth, my uncle said, “Okay, give me five good reasons why I should give you a job.”

I don’t remember the first four, but I clearly remember the last one: I looked Uncle Fausto in the eyes and said, “Because we need it at home.”

He studied me thoughtfully, saying nothing. Finally he nodded his head. “Fine,” he said, “if you’re ready to go at five A.M., I’ll put you to work.”

That next morning, I waited outside by Uncle Fausto’s truck fifteen minutes early, eager to prove myself. No special treatment followed. I was dropped off with a crew of mostly men and started at the bottom of the migrant-worker ladder—pulling weeds. By the end of my two months, I had moved up several rungs, from pulling weeds in the cotton and tomato fields to picking and hauling the crops, working with sorting and counting machines, and finally taking over one of the coveted tractor-driving positions.

During breaks, I kept to myself, pulling out a book I’d brought to keep up my studies and to feed my mind so that I could focus on the physical challenges of work and not be overwhelmed by menial or difficult tasks. I was proud that I could work harder than anyone else, not because of a difference in abilities but probably because of the urgency that drove me—the strong sense of purpose that came from the knowledge that every penny earned would put food on the table for my parents and siblings and would allow me to help improve my family’s status quo.

When I did socialize at night with my cousins and my uncle, the main subject of interest was boxing. And it was in this context that I would be given the nickname “Doc,” perhaps as a hint of things to come. But there was no medical connection, at least not for many years.

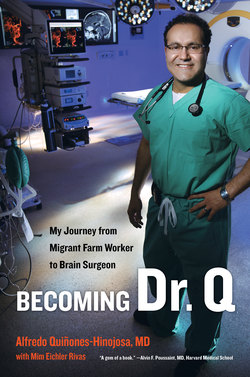

In Mexican culture, people are often given more than one nickname; we might have several that are loosely related to one another. On my first visit to Mendota with my family, most of my nicknames had been Americanized versions of Alfredo—from Freddy, to Alfred, Fred, and Fredo. At fourteen, as I was introduced to Rocky, the classic underdog, I was given a rash of new nicknames. First was the affectionate “Ferdie” that my uncle dubbed me in honor of Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, the famous boxing physician who had been Muhammad Ali’s beloved cornerman and personal doctor. Then he and my cousins started calling me Dr. Pacheco, which then morphed into “Doctor” and ultimately just “Doc.”

When everyone in the fields heard my family calling me Doc or Dr. Pacheco, they assumed that the nicknames explained why I read so much and was so intense and meticulous in everything I did—as if each task were a matter of life and death. Some of them believed that I was a doctor!

Looking back, I know that part of my intensity stemmed from my percolating anger that my family’s situation hadn’t improved. Some of my anger was directed at my father, no doubt, because so much had fallen on my mother’s shoulders. He blamed himself for the loss of the gas station, but after five years, I thought it was time for him to move on. Yet he was stuck. But even more intense than the anger was the war I was fighting against a rising feeling of hopelessness. The only way I knew to combat it was to work myself to the bone and squeeze every cent out of every second. After two months of this extreme regimen, while refusing to spend any of my earnings, I had dropped to ninety-two pounds. My normally round face was drawn, with sunken cheeks, and I had to punch three holes in my belt to hold up my pants.

Uncle Fausto frequently pointed out that I needed new clothes. Finally, he announced that whether I liked it or not, we were going to go shopping on my last Sunday in Mendota. “Okay, Dr. Pacheco,” he said, as my cousins and I entered the men and boys’ store that sold an array of popular brands, “buy yourself a new wardrobe.”

I stood there frozen, not wanting to even look at the clothes, or worse, to spend a dime of what I’d earned. But how could I disobey my uncle, whose generosity had allowed me to prosper?

Seeing my paralysis, Uncle Fausto shrugged and proceeded to pick out two pairs of jeans and two shirts in my size that he knew I would like, and then headed for the cash register. When I argued that such items could be bought more cheaply in Mexico, he appeared not to be listening. “Doc,” he said, “give me your wallet.”

“No,” I refused.

“Freddy, give me your wallet.”

Tears streamed down my face. My cousins lowered their eyes. Finally, I gave in, removed the money, just over fifty dollars, and paid for the clothing that I desperately needed, and secretly wanted.

Uncle Fausto taught me an important lesson on that shopping trip. He wanted me to know that taking care of myself wasn’t selfish and that while sharing the fruits of my labor with others was admirable, hard work should bring a few personal rewards too. To put a fine point on that message, the next day, when he and my cousins took me to the Greyhound station, just before I boarded the bus, Uncle Fausto surprised me with the gift of his Walkman, complete with tapes of American rock and roll. He had seen me pricing tape players at the store and knew how badly I wanted one. It was one of the most generous presents I’d ever received.

One of the few gifts to rival it came within a day, upon my return home. When I stepped off the bus in Mexicali, Mamá burst into tears the moment she saw me—ninety-two pounds of skin and bones. But I told her that I had something for her that would make her feel better. When we were home, just the two of us in the kitchen, I reached into my right sock, under the ball of my foot, and removed the roll of bills that I had protected with every molecule of my energy on the bus ride back to Mexico. About fifty bucks less than one thousand dollars. The amazement and relief that shone on my mother’s face when I turned the money over to her—enough to feed us for a year and put money away for the future—was the greatest personal reward that I could have received.

I had been back from Mendota for nearly a year when my mother finally persuaded me to buy a pair of used boxing gloves so that I could realize my dream of working out at a gym in Mexicali. By then, I’d gained back the weight I’d lost, and before long, I was working my way up to lightweight status at 130 pounds. Part of my motivation, I confess, was that I was tired of having my butt kicked, being a target, and having to surround myself with bigger guys for protection. A part of me also entertained the idea of getting revenge against a particular punk who had embarrassed me many years earlier. Later, to my shame, I used my boxing skills outside the ring to call him out on the street and beat him badly—a wrong that would be on my conscience for years. I would then learn the truth of the Kaliman philosophy “Revenge is a poor counselor.”

But when I was pummeling the punching bag, all I knew was that life had been beating us down and I had to find a new way to respond. My stint as a boxer taught me that I could do more than bob and weave defensively in the face of a challenge; my training helped me fight back, even to be the aggressor when necessary. The first two of my three fights in the ring—which I won—easily confirmed this conclusion. But in the third and last fight, in which I faced a physically overpowering opponent who left me to taste my own blood, I wasn’t so sure—especially when he knocked me to my knees just before the bell in the last round. Still, I had a choice—to quit or to stand up and finish the fight, even in defeat. By choosing the latter option, I learned an essential lesson: it’s not defeat I should fear; more important than whether I won or lost was how I responded to being knocked down and thrown off balance.

Though this was my last official fight, boxing had given me what I needed at the time—an opportunity to hit back. I also discovered that, like those corner breaks that allowed me to recharge during fights, there were ways to recharge my batteries in other pursuits. Eye-opening! But I still had plenty of anger, as there was a need for a surrogate to blame for the misfortunes that had gone on for too long. Rather than taking my fight to the ring, however, I started reserving my anger and rebellion for the forces, institutions, and authorities that most controlled my life. At this time, the major injustice that ate at me was the ongoing bifurcation of the social classes in my country that devalued human beings in the bottom economic strata, as if only those at the top with political connections, wealth, and means were worthy of respect and opportunity. Part of my fight was not to allow those values to get to me.

Always, my grandparents provided a guiding light for how to respond productively to hardship. Now they were getting up in years and both battling serious illnesses. Though I understood in theory that they wouldn’t be around forever, Tata Juan and Nana Maria had always been so much larger than life that I couldn’t imagine their being taken from this world.

Yet on a day like any other day, one of my cousins arrived at the director’s office of my school to request that I be released from class, explaining that my grandfather—afflicted by metastatic lung cancer—was dying and had asked for me. We sped to my grandparents’ home, and as I rushed into Tata’s room, I thought I was too late. He seemed to be staring off into space, already gone in spirit. When I approached him, however, I saw that his eyes were shut.

“Tata,” I said softly in his ear, leaning in close, one hand on his shoulder and the other on the weathered skin of his cheek. “It’s me, Alfredo.”

“Oh, yes,” he replied with effort. “Alfredo.”

My tears began to fall helplessly. In recent months, with cancer slowly and painfully killing him, I had visited often but rarely gotten him to talk much. Though I had seen him declining, I wasn’t ready to say good-bye.

In the otherwise silent room, the sound of his breathing and the ticking of a small clock near his bedside were unforgettable. Then my grandfather slowly opened his eyes and asked softly, “Do you remember when we would go to the Rumorosa Mountains?”

“Yes, I do. Always.”

“Me too. You used to call ‘Tataaaahhhh! Tataaaahhhh!’ ”

“I remember.”

“You know,” he said, just before he closed his eyes and offered a final smile, “I really enjoyed those times.”

Tata’s dying message assured me that I should not be afraid to climb mountains, no matter how treacherous, and that I could even take joy in doing so. He wasn’t telling me how to do that but wanted me to know that I could continue to call on him whenever I felt lost.

After Nana Maria passed away two years later, I felt her presence with me too—though her message was to be careful and to look out for pitfalls. I hope she forgave me for not being at her side more when she was dying. After a lifetime as a healer, helping to bring hundreds of lives into the world, Nana went to the grave knowing that no one had ever died in her care. But I was surprised to learn from my father that until the end, she was afraid of death and especially the loneliness of not knowing what was on the other side. My father also told me that in spite of her fear, when her time came she was ready. Nana discovered what many of us will never know until we are there—that no matter how many times we defy the odds, we all reach the moment where the only way out is surrender. Until then? Give it everything!

Christmas 1985 was eventful for a few reasons. At the age of seventeen, almost eighteen, I was on my way to becoming one of the youngest students ever to graduate from the training program at the teaching college that was my stepping-stone to the future. With excellent grades and teachers’ recommendations, once I graduated I would wait to see where I would be assigned in Mexico to begin my journey as an elementary school teacher. I also had a wonderful girlfriend at the time, a beautiful, bright young lady from a well-to-do, respected family. Our courtship was new, but we were both serious enough about our futures to enter into a meaningful relationship.

After many difficulties, I was confident that brighter days were around the corner, as I told my cousin Fausto and his friend Ronnie when they drove down in Fausto’s truck from Mendota for the Christmas holiday. My hope, I explained to them, was that I’d land a plum assignment for my first teaching post, ideally in one of the bigger cities close to home. The government sometimes sent newer teachers without the right family connections to out-of-the-way locations where there was little money to be made and few options for pursuing further education. But given my excellent academic record, I was sure to be rewarded with the right job—or so I expected.

In the best of moods, we decided to drive into Mexicali to join some of my friends for holiday parties. With Fausto’s truck, we had wheels and could make the scene in style—a big plus for me, given that I usually had to ride the bus to such destinations and then walk an additional three miles or more in extreme heat or cold. We were so mobile, in fact, that not long after arriving at the party in Mexicali, Fausto and Ronnie suggested we continue on to other parties across the border in Calexico, California.

Small problem. I wasn’t carrying my passport. Since I hadn’t planned to cross the border, I’d left it at home. Fausto offered to drive us back to my house for it, but I didn’t see a reason to drive two hours just for a little piece of paper. By the time we did that, the parties would be over. “Never mind,” I told Fausto, “I won’t need it. They hardly ever stop us.”

We approached the checkpoint at the border crossing. The agent, seemingly in a cheery holiday mood, started to wave us through when something appeared to catch his attention and he gestured for us to stop.

Standing at the driver’s side, the American agent asked Fausto, in English, where he was headed. Fausto, without an accent, explained that he was from Fresno but was visiting family for the holidays and was just going across the border for a party.

The agent nodded. Then he asked Ronnie, “Where are you from?”

Ronnie answered, “Fresno.” The agent took him at his word.

Hoping to avoid more questions, I pretended to be looking very closely at something outside the window, up in the sky. The agent said,

“You! Where are you from?”

“Fresno,” I answered, mimicking Fausto and Ronnie’s tone and pronunciation. My knowledge of the English language in this era was close to nada.

“And how long you lived in Fresno, son?” the border agent asked.

“Fresno,” I nodded and smiled, clueless.

The agent then asked for documentation and, of course, I didn’t have any.

Within seconds, a group of agents surrounded the truck. After much discussion, they allowed Fausto and Ronnie to go but detained me. A full two hours of interrogation followed, during which I repeatedly insisted that I had simply forgotten my passport and meant no harm or crime. I knew that I couldn’t give them my name, however, because they would then suspend my passport for good. I also couldn’t tell them what I did or where I was from. But I couldn’t lie.

A Spanish speaker, the border agent who stopped us wanted blood. He could see I had nothing on me, as I was wearing only lightweight shorts, a tank top, and flip-flops. He began to threaten harm to my loved ones, even though he obviously didn’t know who they were. Not getting anywhere, he locked me in a freezing cold room, as close to a cell as I would ever inhabit. Curling up in a fetal position in a futile attempt to get warm, I cried myself to sleep, certain that my life was ruined.

Before dawn, another agent came to unlock the door and found me on the floor. A compassionate man, he was clearly upset with the other agents for holding me in such conditions so long without food and water. The agent apologized, handed me money for breakfast, and sent me on my way.

Lesson learned. My better judgment had clearly been clouded. The idea that I didn’t have a plan in case I was stopped was bad enough. But in thinking that I could deceive the border patrol agent who first approached the car, I stepped over the fine line between confidence and arrogance. With due remorse, I resolved never again to travel without my passport.

After that ordeal, I wasn’t sure that I wanted to travel again. But extenuating circumstances changed my attitude. Much to my shock, as soon as I graduated from college, I learned that, because of the political situation in Mexico, my academic credentials hadn’t helped me get the assignment I’d wanted. Instead, I was to start work right away in a very remote, rural area. The better jobs in cities near universities had all gone to students from wealthier and politically connected families. How could the fight be so blatantly rigged? What about merit? What about talent and hard work? What about justice and equality?

Without realizing it, I was already applying what I’d learned of the American dream from my two visits to the San Joaquin Valley, first at age eleven and then at age fourteen. I wanted to believe that I could travel to Faraway in my own country and have adventures, meeting opportunity and success along the way. I wanted to believe that I could be like my hero, Benito Juárez, and come from nowhere to make important contributions to my country. I most wanted to believe that poor and politically ignored people like me were not powerless. For a decade, during which economic troubles exacerbated poverty and suffering, the once-thriving middle class had been left in the dust. Now I was finding out that the promise that had sustained me—that people like me who had sunk to the bottom could eventually alter our own circumstances—was nothing but a fairy tale.

My future was suddenly in question. Did I even want to be an elementary school teacher? Had I really excelled, or had learning just come easily to me? As I relived the recent years of my education, I realized that I’d felt little passion for my subject matter and now, more than ever, resented this system that had lured me in with promises it couldn’t keep. Had I chosen my path because becoming a teacher was practical, because someone else had done it and had left me a trail? Had I given up on the dreams that had roused my fighting spirit from the time I was a little boy?

Everything at this point appeared more difficult than before, and at times my situation seemed hopeless. At moments, I even wondered whether my life was worth living, whether anyone would miss me if I died. Yes, I had a family that loved me and a girlfriend who thought I had something to offer. But perhaps they were mistaken. Maybe everyone would be better off without me.

No one was able to explain to me that I was probably suffering from an overdue bout of depression or that my disillusionment was probably age-appropriate. No one was there to mention that this dark period would help me in years ahead—allowing me to empathize with patients and to understand their struggles.

One image kept me from losing all hope: the memory of my mother’s jubilant face when I returned from Mendota and handed her my earnings. That hard-earned cash proved that people like me were not helpless or powerless. That was worth something, I had to admit. And I also took some comfort from a dream that had come to me during this time of near despair. In it, a shadowy stranger assured me that better days lay ahead and that I could be the architect of my destiny, although I would have to leave all that was familiar to do so. I asked the stranger how I would know that I was on the right path. He told me that a woman would appear to accompany me at the right stage of the journey; she would be fair-haired and have green eyes.

The dream gave me few other specifics. However, clinging to the image of my mother’s face when I’d returned home from working the fields the last time, I decided I could still become a teacher if I made a few adjustments in my plan. If I returned temporarily to Mendota, I could earn enough money to buy a car and also put aside some of my earnings to supplement my meager income when I returned to Mexico to begin my community service job. Uncle Fausto kindly agreed to put me back to work at the ranch, where I enjoyed my reclaimed status as Dr. Pacheco. Before long, I accumulated seven hundred dollars of earnings and this time needed no persuading to buy myself a wreck of an old Thunderbird at a local used-car dealership.

My dream of fixing up the car’s interior like a Las Vegas attraction—with photos of movie stars, a pair of dice, some religious iconography, and a cassette player for blaring the heavy rock I now loved—would have to wait. But in the meantime, that wreck of a Thunderbird traveled much farther and back again than its makers probably ever imagined.

Toward the end of 1986, as I approached my nineteenth birthday, I felt my life’s journey was nearing a crossroads. While I fought the idea of leaving Mexico for longer than a stint here and there and refused to give up wholly on finding a teaching position that would pay me a small salary, deep down I knew that it was only a matter of time before I migrated north.

I thought of my girlfriend, of course, and the possibilities of building a life together. But what could I offer? Then I recalled all my nights on the roof watching those fast-moving, action-seeking little stars—all going somewhere exciting, beyond the limits of my imagination. There was my answer, as certain as the fixed planets that I now knew hovered in the night sky.

Again, the opportunity to continue working at the ranch in Mendota was central to my thinking. The idea was to go there for a couple of years, returning periodically, like Uncle Jose, with money and help for the family. I hoped I could soon rise to Uncle Fausto’s level, which would enable me to put aside enough money to come back to Mexico and study at the university. I wouldn’t need political connections because I would be a man of means unto myself.

With that plan in mind, though I hadn’t made a final decision or revealed my thoughts to anyone other than Gabriel, he and I decided to go up to Mendota for a few weeks before Christmas to earn some money for the holidays. We would then bring Fausto and Oscar back with us just before New Year’s to enjoy the local festivities. After that, I would drive my cousins back home and either drop them off (as Oscar was finishing high school and Fausto was in his first year at Fresno State) and return home or stay at least until the following summer.

True to the plan, we worked in Mendota over the holiday, and then a few days before New Year’s Eve, I rounded up my cousins and Gabriel, and the four of us hopped into my Thunderbird to make the now-familiar drive through central California toward San Diego and then east to Calexico to cross the border for home. After my earlier ordeal, I made sure to carry my passport wherever I went, so I wasn’t worried about the border crossing, even if we were stopped. Besides, I thought, lightning rarely strikes twice in the same place.

Not so fast!

We weren’t stopped that day. But on New Year’s Eve, now back in Mexico, the three of us decided to drive back over the border to Calexico, at which point a couple of border agents stopped us and asked to see our passports. We showed them the documents, and everything was fine—until the agent asked when I had last entered or left the country and where I had been. “Fresno,” I said. “Travel. Visit family.”

Fausto and Oscar waited in the car as Gabriel and I were escorted into a room, where a two-hour interrogation ensued. The agents had nothing on us. Finally, they asked if we’d ever worked during our travel and family visits to the United States. “What?” I asked indignantly, as if that notion were the craziest thing I’d ever heard. All this time I had been working with only a tourist visa—clearly illegal. Now I was sweating bullets, but I managed to appear cool.

When they were about to let us go, one of the agents said, “Fine, let me take a look at your ID again.”

But instead of letting me pull out the paperwork to show him, he grabbed my wallet, where he immediately found fairly recent pay stubs, issued in the United States, with my name on them. And there was a pay stub with Gabriel’s name on it, too.

We were now officially in trouble not just for working without a permit but for lying about it.

And that was how lightning struck twice and I had my passport confiscated, as did Gabriel. When we came outside, Fausto and Oscar were waiting in the Thunderbird. I got behind the wheel and followed the agent’s directions as he pointed us back south toward Mexico.

If I had been at all ambivalent about leaving home and spending a longer period of time in the United States, that incident sealed my fate. Granted, I had no passport, no legal means of crossing the border again. But that technicality wasn’t going to stop me from executing a new plan. There was no time to make my good-byes, no time to explain myself or express my regrets to my friends or my girlfriend.

I had searched my heart and looked to the wisdom of my grandparents, who seemed to be sending me the same message: go! The time to leave home, family, and everything I knew in this world had arrived. There was no need to be afraid or to think that I couldn’t do it. All I needed to take with me was Tata Juan and Nana Maria’s lasting guidance and everything that I’d been blessed to learn in my eighteen years. That, and the sixty-five American dollars I had to my name.

As I devised the strategy I planned to execute, auspiciously, on New Year’s Day, 1987, I spent the hours before dawn sitting outside in the darkness without a star in the sky. My thoughts wound back to my trips to the mountains with Tata Juan as we made our way to the little town of Rumorosa, along the steep edges of the Sierras. I remembered how dangerous the road was and the fact that many cars had fallen down the cliffs in terrible weather and in other mishaps. And yet my grandfather had chosen not the safest route but the one that provided the most interesting little stops along the way. While Tata was as eager to get to the cabin as I was, he didn’t agree with me that the shortest and most direct route between two points was best. He wanted to show me what I would miss if I focused only on my destination.

Desperate situations—like the one in which I found myself on the eve of my nineteenth birthday—require desperate choices. Having made my decision, I couldn’t allow any regrets or second thoughts to deter me. Don’t look back, I told myself. I had to go forward to find my destiny, crossing the border fence to see where the path on the other side would take me. I had to act boldly, decisively, and immediately. And I had to climb to the top and jump.