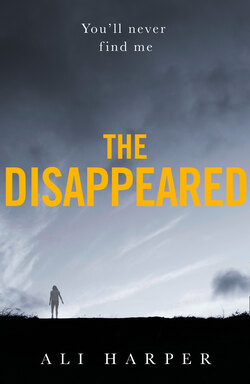

Читать книгу The Disappeared - Ali Harper - Страница 6

Chapter One

ОглавлениеHad I known our first client would be dead less than twenty-six hours after signing the contract, I might not have been so thrilled when she pushed open our office door.

I once read that hindsight is always twenty-twenty, but I disagree. Hindsight distorts the picture, makes us believe we could have done something different, something better. Hindsight opens the door to ‘if only’ and the ‘if only’ is what kills you.

It had been five weeks, four days and six hours since we’d opened for business and in all that time no one had so much as glanced through the window. Despite adverts in every local listings magazine, the only phone calls we’d fielded were cold ones – did we want double-glazing, roof repairs, a conservatory? Jo had been getting increasingly aggressive with each caller. The strain was getting to both of us.

I was alone in the office that Friday afternoon. Jo had nipped out in the company’s battered Vauxhall Combo, ostensibly to buy printer ink – but really, I knew she’d be checking out the latest surveillance equipment at The Spy Shop, down on Kirkstall Road. Jo’s my best mate, business partner, and a gadget freak: not always in that order.

I’d been at my desk when I’d noticed the woman pacing the pavement opposite. I’d watched her through the gaps in our vertical strip blinds. She’d smoked two cigarettes, crushing out the stubs with the heel of her boot. Truth is, I’d been willing her to cross the street and come on in.

So when she did step through the door, my pulse quickened and my mouth went dry. I slid my packet of Golden Virginia into the top drawer.

She was nervous, obviously so. She had blonde hair, cut kind of choppy round her face and she kept touching it, scratching at the back of her neck.

‘Hi,’ I said. I almost fell over the desk in order to shake her hand. She allowed our palms to touch for less than a second, but long enough for me to register the coolness of her skin. ‘Welcome to No Stone Unturned.’

She glanced around. Our office used to be a corner shop, situated at the end of a red-brick terrace, so it has windows on two sides. The rent is cheap, and the interior walls are panelled in a wooden laminate that wobbles whenever we shut a door or slam a drawer too hard.

I watched her drink in the details – the cheap brown carpet tiles, the battered filing cabinet we’d bought from Royal Park Furniture Store – purveyor of cheap crap to low-class landlords. I noticed the pot plant Jo had supplied was looking thirsty.

‘Are you missing someone?’ I asked.

‘Sorry.’ Her voice was soft, well-spoken – the kind of voice that could have worked for The Samaritans.

‘That’s OK,’ I said. ‘It must be diff—’

‘Could I speak to an investigator?’

I straightened my spine, remembered to ground myself through the soles of my feet. ‘You are. I’m the …’ I wanted to say proprietor but settled for ‘lead investigator.’ Jo would have punched me.

‘Oh.’ A crease appeared on the woman’s forehead. I cursed the fact we’d given up wearing suits on day four.

‘I’m Lee,’ I said, ‘Lee Winters.’ It still felt like a lie on my lips, even though three months before I’d made it official. I wasn’t born Lee Winters. The Buddhists believe you shed your skin every seven years, and changing my name was my way of forcing the process. I pointed at the two armchairs and coffee table in the corner of the room. ‘Take a seat.’

She didn’t move. I positioned myself between her and the exit and gestured at the seats again.

‘I shouldn’t have come,’ she said.

‘Give it a chance. Why don’t you tell me what the problem is, and we’ll see if we can help?’

‘I didn’t know where else to turn.’ Her right hand twisted the gold band on her wedding finger. She turned it round and round, over and over. The ring seemed loose, a little too big on her slender fingers. I examined my own bitten fingernails, the silver rings I wear like knuckledusters. As she opened her mouth to speak, I heard a noise behind me. I turned to see Jo pushing through the door, a box of paper in her arms and a Spy Shop carrier bag dangling from her wrist.

‘Hi, Jo.’ I raised my eyebrows and nodded, trying to telepathically answer her unspoken questions.

Jo dropped the reams of paper on the edge of my desk and beamed at the woman. ‘You’ve come to the right place,’ she said.

Jo sounded so certain I felt my shoulders relax. The woman stared at Jo. Most people do. Jo inherited her Afro-Caribbean curls from her Jamaican grandfather on her mother’s side. Her startling blue eyes came from her Liverpudlian dad. They make a stunning combination. It must have been windy out – her hair was wild even by Jo’s standards. The woman turned to me.

‘Is there somewhere private we can talk?’ she said, pushing up the sleeve of her dark jacket.

‘Go through to the back room,’ said Jo, putting a casual arm across the woman’s lower back and propelling her forward. ‘I’ll make you a nice, strong cup of tea. Looks like you could use one.’

We’ve got three rooms out back. I use the word ‘room’ in its broadest sense – you have to step outside the kitchenette in order to open the fridge, and how anyone could ever use the gas cooker is a mystery. There’s a toilet next door, but when you sit on it, your knees graze the door. The windowless back room contains a punchbag, as well as a small wooden table covered with decaying green felt, and three chairs. The bag came from the boxing gym round the corner and dangles from the ceiling. I’d spent much of the previous six weeks in there, punching till my arms ached and beads of sweat flew, trying to fight the worry that I’d blown my inheritance on a business that wasn’t ever going to see a client.

The back room also has a broom cupboard – now converted to Jo’s spy equipment store – which has a safe cemented into the brick wall at the back of it. That small metal box had sealed the deal when we’d been looking for premises. We figured the previous tenants must have been dope dealers.

I cleared a space on the table by stashing the playing cards to one side and setting the ashtray on the floor.

‘You smoke in here?’ She didn’t miss much, I thought.

‘No. Well, only in emergencies. I mean, sometimes clients—’

‘Would you mind if I smoked?’ she asked.

‘Oh. No, not at all. I’ll open the kitchen window.’

When I got back, she’d lit a long, dark brown cigarette, and I noticed the tremor in her hands. Jo popped her head round the door and handed me a new client file.

‘Right, yes,’ I said. ‘Thank you.’

I heard the click of the kettle from the kitchenette. I opened the file, spread it on the table in front of me and cleared my throat. ‘So, how can we help you?’

‘I don’t think you can.’ She blew a cloud of smoke into the air. ‘I was stupid to come.’

I bristled at that. It’s personal – the business; my chance to put right what I’ve done wrong. OK, this woman was our first potential proper client, but it wasn’t like we didn’t have previous experience. Besides trying to track down my own dysfunctional family, last year Jo and I travelled to the other side of the world to find a missing person – Bert’s wife. Bert lived next door to my mum, took care of her in what turned out to be her last years. Me and Jo managed to track down his missing mail-order bride, in Thailand, despite not knowing the language. We have a natural flair for finding people.

‘You had your reasons,’ I said.

‘I saw your ad. About reuniting families.’

I extracted Jo’s Initial Enquiry Form and read the tag line out loud. ‘Are you missing someone?’

‘Yes.’

I waited a moment, but she didn’t expand. I coughed again and wished I had a glass of water. ‘Who? Who are you missing?’

‘My son.’

Another silence. ‘What’s his name?’

‘I don’t know what to do.’

I tried to sound like a well-seasoned investigator, battle weary. ‘Start with his name.’

‘Jack.’

I made a note on the form as she exhaled. Instinct told me to stick to simple questions. ‘Age?’

‘He’s 22.’ She stubbed out the first cigarette, which was only a third of the way smoked, and lit another straightaway. ‘I was very young,’ she said, in answer to a question I hadn’t asked. But it did make me think. I stared at her, but she held her cigarette to her lips almost permanently, so that her hand obscured the bottom half of her face. It was hard to put an age to her. Older than me, but I’d be surprised if she’d hit forty. ‘He’s had problems.’

‘Problems?’

‘He’s driven us to our wits’ end. We’ve given him everything. Cash. Car. You name it.’

‘And now he’s missing?’

‘Not a word in three months.’

I wrote that down. ‘Tell me about the last time you saw him.’

‘Christmas. He came round for dinner, borrowed twenty pounds.’

‘This was to your house?’

‘Yes.’

‘In Leeds?’

‘Manchester. But he came back to Leeds. He’s a student here. Or he was.’

‘Where does he live?’

She sat a little straighter in the chair and leaned in. ‘That’s why I chose you. You being so close, I mean. The last address I had for him was a squat on Burchett Grove. It’s not very far from here.’

I got a shot in my veins; the feeling’s hard to describe, like I’m kind of coming alive. A trail, a scent of someone. I knew Burchett Grove. Locals called it Bird Shit Grove. It was ten minutes away, in Woodhouse, an area of Leeds favoured by the politically earnest. This was my neck of the woods.

‘Which one?’

She put her hand in her jacket pocket and took out a piece of paper, ripped from the pages of a spiral bound notebook. She handed it to me. ‘I hate going round there.’ Her whole body juddered as if to prove her point. ‘The last time I went, they said he’d moved. I don’t know if they were telling the truth.’

I probably grinned, reading the address. There are two squats on Burchett Grove, and I’ve known people living at both of them over the years. If he was there we could have the case cracked in minutes. I might even know the guy. ‘You got a photo?’

She picked her handbag up from the floor and flicked the clasp. After some rummaging she pulled out a photograph of a lanky teenager in school uniform.

I frowned at her. ‘A recent one?’

She closed her eyes for a moment. ‘He hates having his photo taken. That’s the sixth form. He dropped out a few months after that.’

‘When did he move to Leeds?’

She scratched at the back of her neck again. ‘Five years ago. Hired a van, insisted on doing it all on his own.’

‘What will you do if we find him and he doesn’t want to see you?’ This was a standard question we’d agreed to ask everyone. We weren’t naive. Families often split for good reasons.

She squared back her shoulders. ‘I can live with that,’ she said. I caught a glimpse of an inner steeliness and I believed her. ‘I just need to know where he is, that he’s OK.’

I told her what we charged, and she nodded. Jo had included a blank contract in the file. I passed it to her and read upside down as she printed her name. Mrs Susan Wilkins. As she filled in her address details, she glanced up at me.

‘There’s another thing. You have to promise you won’t contact my husband.’

She stared at me with piercing blue eyes. I shrugged. No skin off my nose. ‘You’re the boss,’ I said.

‘He’s washed his hands of Jack. He’ll go berserk if he knows what I’m doing.’ She pushed the contract back to me, the still-damp ink glistening in the fluorescent overheads.

‘You haven’t put your mobile.’

‘I dropped it,’ she said. She raised her eyebrows at me. ‘Silly of me. They’re replacing the screen. I’m staying at the Queens. Could we perhaps agree a time each day where I call you and you give me a progress report?’

‘OK.’ I handed her a business card with my mobile number, and she tucked it into her jacket pocket. I cleared my throat. ‘So, there’s just the matter of the fees.’

‘Yes.’ She opened her bag again and paid the deposit – two hundred pounds – in cash, counting out ten-pound notes from a brown envelope. No Stone Unturned, Leeds’s brand new missing persons’ bureau, had its first client.

And it promised to be a straightforward case – middle-class kid, starts college, smokes dope, forgets to ring his mother. We’d have this in the bag by the weekend, I remember thinking. I had no sense of what was in store for us. Now, as I sit here, trying to write this report and pick through the pieces of the last few days, it’s easy to see that the signs were all there, I just didn’t read them. We fit the pictures to the story we want to hear. And what I wanted to see was a middle-aged, middle-class woman, desperately seeking her son.