Читать книгу Solitaire - Alice Oseman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеI AM AWARE as I step into the common room that the majority of people here are almost dead, including me. I have been reliably informed that post-Christmas blues are entirely normal and that we should expect to feel somewhat numb after the ‘happiest’ time of the year, but I don’t feel so different now to how I felt on Christmas Eve, or on Christmas Day, or on any other day since the Christmas holidays started. I’m back now and it’s another year. Nothing is going to happen.

I stand there. Becky and I look at each other.

“Tori,” says Becky, “you look a little bit like you want to kill yourself.”

She and the rest of Our Lot have sprawled themselves over a collection of revolving chairs around the common-room computer desks. As it’s the first day back, there has been a widespread hair-and-make-up effort across the entire sixth form and I immediately feel inadequate.

I deflate into a chair and nod philosophically. “It’s funny because it’s true.”

She looks at me some more, but doesn’t really look, and we laugh at something that wasn’t funny. Becky then realises that I am in no mood to do anything so she moves away. I lean into my arms and fall half asleep.

My name is Victoria Spring. I think you should know that I make up a lot of stuff in my head and then get sad about it. I like to sleep and I like to blog. I am going to die someday.

Rebecca Allen is probably my only real friend at the moment. She is also probably my best friend. I am as yet unsure whether these two facts are related. In any case, Becky Allen is very pretty and has very long purple hair. It has come to my attention that, if you have purple hair, people often look at you. If you are pretty with purple hair, people often stay looking at you, thus resulting in you becoming a widely recognised and outstandingly popular figure in adolescent society; the sort of figure that everyone claims to know yet probably hasn’t even spoken to. She has 2,098 friends on Facebook.

Right now, Becky’s talking to this other girl from Our Lot, Evelyn Foley. Evelyn is considered ‘retro’ because she has messy hair and wears a necklace with a triangle on it.

“The real question though,” says Evelyn, “is whether there’s sexual tension between Harry and Malfoy.”

I’m not sure whether Becky genuinely likes Evelyn. Sometimes I think people only pretend to like each other.

“Only in fan fictions, Evelyn,” says Becky. “Please keep your fantasies between yourself and your blog.”

Evelyn laughs. “I’m just saying. Malfoy helps Harry in the end, right? He’s a nice guy deep down, yeah? So why does he bully Harry for seven years? Enormous. Closet. Homosexual.” With each word, she claps her hands together. It really doesn’t emphasise her point. “It’s a well-established fact that people tease people they fancy. The psychology here is unarguable.”

“Evelyn,” says Becky. “Firstly, I resent the fangirl idea that Draco Malfoy is some kind of beautifully tortured soul who is searching for redemption and understanding. Secondly, the only non-canon couple that is even worth discussion is Snily.”

“Snily?”

“Snape and Lily.”

Evelyn appears to be deeply offended. “I can’t believe you don’t support Drarry when you ship Snape and Lily. I mean, at least Drarry is a realistic possibility.” She slowly shakes her head. “Like, obviously, Lily went for someone hot and hilarious like James Potter.”

“James Potter was a resplendent twat. Especially to Lily. J.K. made that quite clear. And dude – if you don’t like Snape by the end of the series, then you miss the entire concept of Harry Potter.”

“If Snily had been a thing, there would have been no Harry Potter.”

“Without a Harry, Voldemort might not have, like, committed mass genocide.”

Becky turns to me, and so does Evelyn. I deduce that I am under pressure to contribute something.

I sit up. “You’re saying that because it’s Harry’s fault that all these muggles and wizards died, it would have been better if there’d been no Harry Potter at all and no books or films or anything?”

I get the impression that I’ve ruined this conversation so I mumble an excuse and lift myself off my chair and hurry out of the common-room door. Sometimes I hate people. This is probably very bad for my mental health.

*

There are two grammar schools in our town: Harvey Greene Grammar School for Girls, or ‘Higgs’ as it is popularly known, and Truham Grammar School for Boys. Both schools, however, accept males and females in Years 12 and 13, the two final years of school known countrywide as the sixth form. So, now that I am in Year 12, I have had to face a sudden influx of the male species. Boys at Higgs are on a par with mythical creatures and having an actual real boyfriend puts you at the head of the social hierarchy, but personally, thinking or talking too much about ‘boy issues’ makes me want to shoot myself in the face.

Even if I did care about that stuff, it’s not like we get to show off, thanks to our stunning school uniform. Usually, sixth-formers don’t have to wear school uniform; however, Higgs sixth form are forced to wear a hideous one. Grey is the theme, which is fitting for such a dull place.

I arrive at my locker to find a pink Post-it note on its door. On that, someone has drawn a left-pointing arrow, suggesting that I should, perhaps, look in that direction. Irritated, I turn my head to the left. There’s another Post-it note a few lockers along. And, on the wall at the end of the corridor, another. People are walking past them, totally oblivious. What can I say? People aren’t observant. People don’t question stuff like this. They never think twice about déjà vu when there could be a glitch in the Matrix. They walk past tramps in the street without even glancing at their misfortune. They don’t psychoanalyse the creators of slasher-horrors when they’re probably all psychopaths.

I pluck the Post-it from my locker and wander to the next.

Sometimes I like to fill my days with little things that other people don’t care about. It makes me feel like I’m doing something important, mainly because no one else is doing it.

This is one of those times.

The Post-its start popping up all over the place. Like I said, everyone is ignoring them; instead, they are going on with their day and talking about boys and clothes and pointless stuff. Year 9s and 10s strut around in their rolled-up skirts and thigh-high socks over their tights. Year 9s and 10s always seem to be happy. It makes me hate them a bit. Then again, I hate quite a lot of things.

The penultimate Post-it I find depicts an arrow pointing upwards, or forwards, and is situated on the door of a closed computer room on the first floor. Black fabric covers the door window. This particular computer room, C16, was closed last year for refurbishment, but it doesn’t look like anyone’s bothered getting started. It sort of makes me feel sad, to tell you the truth, but I open C16’s door anyway, enter and close it behind me.

There’s one long window stretching the length of the far wall, and the computers in here are bricks. Solid cubes. Apparently, I’ve time-travelled to the 1990s.

I find the final Post-it note on the back wall, bearing a URL:

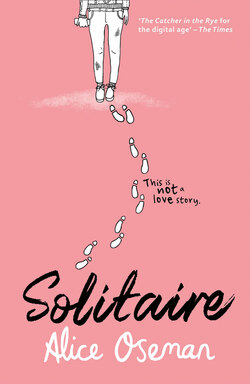

SOLITAIRE.CO.UK

In case you live under a rock or are home-schooled or are just an idiot, Solitaire is a card game you play by yourself. It’s what I used to spend my IT lessons doing and it probably did a lot more for my intelligence than actually paying attention.

It’s then that someone opens the door.

“Dear God, the age of the computers in here must be a criminal offence.”

I turn slowly around.

A boy stands before the closed door.

“I can hear the haunting symphony of dial-up connection,” he says, eyes drifting, and, after several long seconds, he finally notices that he’s not the only person in the room.

He’s a very ordinary-looking, not ugly but not hot, miscellaneous boy. His most noticeable feature is a pair of large, thick-framed square glasses, the sort similar to those 3D cinema glasses that twelve-year-olds pop the lenses out of and wear because they think it makes them look ‘rad’. God, I hate it when people wear glasses like that. He’s tall and has a side parting. In one hand, he holds a mug; in the other a piece of paper and his school planner.

As he absorbs my face, his eyes flare up and I swear to God they double in size. He leaps towards me like a pouncing lion, fiercely enough that I stumble backwards in fear that he might crush me completely. He leans forward so that his face is centimetres from my own. Through my reflection in his ridiculously oversized spectacles, I notice that he has one blue eye and one green eye. Heterochromia.

He grins violently.

“Victoria Spring!” he cries, raising his arms into the air.

I say and do nothing. I have a headache.

“You are Victoria Spring,” he says. He holds the piece of paper up to my face. It’s a photograph. Of me. Underneath, in tiny letters: Victoria Spring, 11A. It has been on display near the staffroom – in Year 11, I was a form leader, mostly because no one else wanted to do it so I got volunteered. All the form leaders had their pictures taken. Mine is awful. It’s before I cut my hair so I sort of look like the girl from The Ring. It’s like I don’t even have a face.

I look into the blue eye. “Did you tear that right off the display?”

He steps back a little, retreating from his invasion of my personal space. He’s got this insane smile on his face. “I said I’d help someone look for you.” He taps his chin with his planner. “Blond guy … skinny trousers … walking around like he didn’t really know where he was …”

I do not know any guys and certainly not any blond guys who wear skinny trousers.

I shrug. “How did you know I was in here?”

He shrugs too. “I didn’t. I came in because of the arrow on the door. I thought it looked quite mysterious. And here you are! What a hilarious twist of fate!”

He takes a sip of his drink. I start to wonder if this boy has mental problems.

“I’ve seen you before,” he says, still smiling.

I find myself squinting at his face. Surely I must have seen him at some point in the corridors. Surely I would remember those hideous glasses. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen you before.”

“That’s not surprising,” he says. “I’m in Year 13, so you wouldn’t see me much. And I only joined your school last September. I did my Year 12 at Truham.”

That explains it. Four months isn’t enough time for me to commit a face to memory.

“So,” he says, tapping his mug. “What’s going on here?”

I step aside and point unenthusiastically to the Post-it on the back wall. He reaches up and peels it off.

“Solitaire.co.uk. Interesting. Okay. I’d say we could boot up one of these computers and check it out, but we’d probably both expire before Internet Explorer loaded. I bet you any money they all use Windows 95.”

He sits down on one of the swivel chairs and stares out of the window at the suburban landscape. Everything is lit up like it’s on fire. You can see right over the town and into the countryside. He notices me looking too.

“It’s like it’s pulling you out, isn’t it?” he says. He sighs to himself. Like a girl. “I saw this old man on my way in this morning. He was sitting at a bus stop listening to an iPod, tapping his hands on his knees, looking at the sky. How often do you see that? An old man listening to an iPod. I wonder what he was listening to. You’d think it would be classical, but it could have been anything. I wonder if it was sad music.” He lifts up his feet and crosses them on top of a table. “I hope it wasn’t.”

“Sad music is okay,” I say, “in moderation.”

He swivels round to me and straightens his tie.

“You are definitely Victoria Spring, aren’t you.” This should be a question, but he says it like he’s already known for a long time.

“Tori,” I say, intentionally monotone. “My name is Tori.”

He laughs at me. It’s a very loud, forced laugh. “Like Tori Amos?”

“No.” Pause. “No, not like Tori Amos.”

He puts his hands in his blazer pockets. I fold my arms.

“Have you been in here before?” he asks.

“No.”

He nods. “Interesting.”

I widen my eyes and shake my head at him. “What?”

“What what?”

“What’s interesting?” I don’t think I could sound less interested.

“We both came looking for the same thing.”

“And what is that?”

“An answer.”

I raise my eyebrows. He gazes at me through his glasses. The blue eye is so pale it’s almost white. It’s got an entire personality of its own.

“Aren’t mysteries fun?” he says. “Don’t you wonder?”

It’s then that I realise that I probably don’t. I realise that I could walk out of here and literally not give a crap about solitaire.co.uk or this annoying, loud-mouthed guy ever again.

But because I want him to stop being so goddamn patronising, I swiftly remove my phone from my blazer pocket, type solitaire.co.uk into the Internet address bar and open up the web page.

What appears almost makes me laugh – it’s an empty blog. A troll blog, I guess.

What a pointless, pointless day this is.

I thrust the phone into his face. “Mystery solved, Sherlock.”

At first, he keeps on grinning, like I’m joking, but soon his eyes focus downwards on to the phone screen and, in a kind of stunned disbelief, he removes the phone from my hand.

“It’s … an empty blog …” he says, not to me but to himself, and suddenly (and I don’t know how this happens) I feel deeply, deeply sorry for him. Because he looks so bloody sad. He shakes his head and hands my phone back to me. I don’t really know what to do. He literally looks like someone’s just died.

“Well, er …” I shuffle my feet. “I’m going to form now.”

“No, no, wait!” He jumps up so we’re facing each other.

There is a significantly awkward pause.

He studies me, squinting, then studies the photograph, then back to me, then back to the photo. “You cut your hair!”

I bite my lip, holding back the sarcasm. “Yes,” I say sincerely. “Yes, I cut my hair.”

“It was so long.”

“Yes, it was.”

“Why did you cut it?”

I had gone shopping by myself at the end of the summer holidays because there was so much crap I needed for sixth form and Mum and Dad were busy with all of the Charlie stuff that was going on and I just wanted it out of the way. What I’d failed to remember was that I am awful at shopping. My old school bag was ripped and dirty so I trailed through nice places – River Island and Zara and Urban Outfitters and Mango and Accessorize. But all the nice bags there were, like, fifty pounds, so that wasn’t happening. Then I tried the cheaper places – New Look and Primark and H&M – but all the bags there were just tacky. I ended up going round all the shops selling bags a billion bloody times before having a slight breakdown on a bench by Costa Coffee in the middle of the shopping centre. I thought about starting Year 12 and all the things that I needed to do and all the new people that I might have to meet and all the people I would have to talk to and I caught a reflection of myself in a Waterstones window and I realised then that most of my face was covered up and who in the name of God would want to talk to me like that and I started to feel all of this hair on my forehead and my cheeks and how it plastered my shoulders and back and I felt it creeping around me like worms, choking me to death. I began to breathe very fast, so I went straight into the nearest hairdresser’s and had it all cut to my shoulders and out of my face. The hairdresser didn’t want to do it, but I was very insistent. I spent my school bag money on a haircut.

“I just wanted it shorter,” I say.

He steps closer. I shuffle backwards.

“You,” he says, “do not say anything you mean, do you?”

I laugh again. It’s a pathetic sort of expulsion of air, but for me that qualifies as a laugh. “Who are you?”

He freezes, leans back, opens out his arms as if he’s the Second Coming of Christ and announces in a deep and echoing voice: “My name is Michael Holden.”

Michael Holden.

“And who are you, Victoria Spring?”

I can’t think of anything to say because that is what my answer would be really. Nothing. I am a vacuum. I am a void. I am nothing.

Mr Kent’s voice blares abruptly from the tannoy. I turn round and look up at the speaker as his voice resonates down.

“All sixth-formers should make their way to the common room for a short sixth-form meeting.”

When I turn back round, the room is empty. I’m glued to the carpet. I open my hand and find the SOLITAIRE.CO.UK Post-it inside it. I don’t know at what point the Post-it made its way from Michael Holden’s hand to my own, but there it is.

And this, I suppose, is it.

This is probably how it starts.