Читать книгу Unexpected - Alison Piepmeier - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеAlison Piepmeier was a scholar of literature, feminism, and disability studies; a prolific columnist and blogger; an activist; a beloved professor and mentor; and a parent. For Alison, these roles and categories were interconnected, so it is unsurprising that in her last and most ambitious work, she tried to draw these strands together: to write a book that included personal witness and analytical rigor, that fused an activist’s fire, a poet’s eye, and a scholar’s care. The manuscript was left incomplete when Alison died of brain cancer, at the age of forty-three, in August 2016.

Before she died, Alison and George communicated by email, then by Skype, about the possibility of his completing the project. Realizing the dimensions of the project and the expertise required, George told Alison that he wanted to bring on their mutual friend Rachel as a co-editor. Rachel, Alison, and George had known each other for years. Like Alison, Rachel and George each have a child with Down syndrome; like Alison, they have written publicly about the experience of parenting, linking it to questions of disability. Rachel’s training in disability studies, feminism, and literature was a perfect complement to the expertise George could contribute to this project. Alison gave her enthusiastic approval to the idea, and Rachel accepted, with equal enthusiasm.

This book is our attempt to complete the manuscript in accordance with Alison’s wishes. It’s mainly composed of Alison’s writing—an assembly that highlights the best of her work, in line with the structure she had set out. Each of us has also contributed a chapter about an aspect of Alison’s work, offering context and appreciation for her achievement.

* * *

In a blog post published shortly after Alison died, her husband Brian McGee wrote, “To share a life with Alison Piepmeier was to be constantly aware of her uneasy relationship with time.” He spoke of “Alison’s unaffected brilliance” and added that “wit and erudition weren’t sufficient to make her the enthusiastic presence, the cheerful dynamo so many of us came to adore. Often, it was Alison’s anxious awareness of the passage of time that provided the abundance of energy she channeled so effectively to teach, to serve her community, to mentor students—and always, always, to write. It was Alison’s anxious awareness of time that frequently had her finishing tasks and moving on to the next challenge hours or days before deadlines.”1

Alison was diagnosed with a brain tumor in early 2010. She died in August 2016. As Brian wrote, her illness “changed her relationship with time”—not only in symptoms, side effects, and radical shifts in her daily routines, but also in facing the shock of medical prediction. “She had to live with the ability of medical professionals to predict, however imperfectly, the most likely dates of her demise. . . . Focus was never Alison’s problem, but nothing was quite so focusing as her physician’s affidavit stating that she had 6–12 months to live.”

Brian put his finger on the distinctive temporalities of illness and disability that writers like Alison Kafer, Ellen Samuels, and Robert McRuer call “crip time.”2 Borrowing from queer theory, these scholars observe that illness and disability can make time slow down or speed up, move backward or sideways, or repeat itself, confounding traditional notions of progress, development, and uniformity. Alison worked with the queer-crip understanding that she might not have the gradual, elongated unfolding of a conventional life span. She lived with the patient’s sense that time is not her own, given how much of it is spent waiting in the shadow cast by the uncertain pronouncements of medical professionals. She also lived with an awareness of how unpredictable a body can become, as the threat of exhaustion and debility challenges the attempt to plan a future program of research and writing. These unusual temporalities can make queer-crip writing feel open-ended, unpolished, and raw. They also invite us to think about the devices used by those who are healthy and able-bodied to mask the fact that all futures are uncertain.

Reading Alison’s drafts of the chapters that became this book, we kept tripping over markers of the unfinished. Both the wit and the hurry, the urgency of prognosis and the linguistic skill she brought to it—a skill under siege by the very illness she sought to narrate—are evident in the placeholders embedded in her drafts:

No epigraph yet.

Brilliant person

But. . . . [transition]

Another person said xxx.

BOOK: Nameless.

That urgency—“always, always to write”—marks her notes to herself, her assessments of what the book was, and was becoming. Her notes mark time and are marked by the consciousness of time: “Synthesis as of 3:00 on May 12,” she wrote to herself once. She was keenly aware of the book as an evolving thing, and in her notes, we see a conversation with herself, an urgent meditation on the book’s direction.

Alison’s original book proposal, shared with us by her editor Ilene Kalish, focused on reproductive decision-making, in Alison’s words, “a feminist disability studies examination of decisions parents and potential parents have to make.” At that time, the book’s proposed title was A Choice with No Story: What Prenatal Testing and Down Syndrome Reveal about Our Reproductive Decision-Making. That focus on reproductive decision-making grew out of Alison’s experiences of pregnancy, birth, and motherhood with Maybelle, who has Down syndrome. It also grew from her extensive interviews of mothers who, facing a diagnosis of Down syndrome in utero, chose either to continue pregnancies or to terminate. As Alison’s original title implies, the mothers attempting to make sense of this situation did so in the absence of narrative—or, more precisely, in the presence of conflicting narratives about the meaning and value of a child with Down syndrome.

In an enthusiastic review of the book proposal for New York University Press, Rachel called Alison’s work “an important and timely project.” She described it as a study of prenatal testing that would collect “the rarely-heard stories of parents and prospective parents who have confronted decisions about a fetus diagnosed with Down syndrome. [Alison] questions the rhetoric of ‘choice’ that surrounds prenatal testing, showing how decisions are shaped and limited by familial and cultural attitudes, as well as available resources. Although prenatal testing is designed to detect a range of genetic conditions, the book zeroes in on Down syndrome because it so often becomes the exclusive focus of the rhetoric and popular understanding of genetic tests.”

In the fall of 2015, editors and other reviewers shared Rachel’s enthusiasm, and soon the project was under contract. Though Alison questioned how much of the manuscript would be personal, or how the personal and the academic modes would fit together, she was clearly moving toward memoir, focusing on her own experience of motherhood and illness:

Chapter 5—sitting/eating together. We’re together @ a moment of sadness. How much should this be about me? How much of any of this is me? What emphasis? I think the emphasis always has to come back to MB [Maybelle], and my head.

But I do think our scholarship is crucial. Who do I see? How does their work connect to what I’m exploring?

“MB, and my head”: these words could be taken as shorthand for two aspects of Alison’s life. She was a parent and a patient, and as such, she realized that her daily life was permeated by unanswerable questions. What is the line between illness and disability? How did Alison’s challenges with language, brought on by a brain tumor, differ from Maybelle’s, associated with Down syndrome?

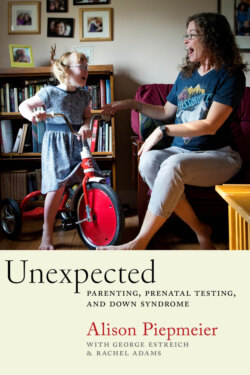

Maybelle and Alison Piepmeier. Source: Trey Piepmeier

Alison had always explored other kinds of writing. She wrote poetry in college, and as George argues in his chapter, her blog contains some of her best writing. Read in sequence, the blog entries can be understood as a single essay. (Indeed, the blog can be seen as a proving ground for this book, a place to mix the minutiae of everyday life with feminist analysis.) But for Alison, this was a new kind of book. It both differs from, and grows out of, her work on nineteenth-century women’s writing (Out in Public: Configurations of Women’s Bodies in Nineteenth-Century America); on zines (Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism); or, with co-editor Rory Dicker, on third-wave feminism (Catching a Wave: Reclaiming Feminism for the 21st Century). It shares with previous work her interest in women, the body, popular culture, and activism.

From the beginning, her insights about gender were inflected by an understanding of the intersections of race and class. As a scholar trained in literary studies, Alison was keenly aware that representations matter. Not only do they reflect prevailing social beliefs, but they also have the power to unsettle, and even transform, dominant attitudes. She was interested in women as social and historical agents, as makers and doers actively engaged in shaping the realities under which they lived. Alison also knew that feminist knowledge is situated knowledge. Even at her most scholarly, she was always present in her writing—her vivid sense of voice and her passions, commitments, and beliefs evident on the page. Her new book was meant to connect her scholarly and theoretical preoccupations with her personal experience and to reach beyond a purely academic audience.

As Alison’s conception of the book evolved, the idea of story remained, a common thread among her varied approaches. She was fascinated by the power of narrative to help and to harm. A parent’s experiences can yield stories that dehumanize their subjects, particularly in the case of intellectual disability, but a different story about the same experiences can recognize dignity and personhood, replacing reduction with complexity. As Alison showed in her study of parent memoirs, these opposing impulses often coincide. While Alison never had the chance to fully theorize her interest in narrative, her approach was in keeping with scholarship in disability studies and medical humanities that recognizes the power of personal stories to serve as a kind of embodied theory. As Elaine Scarry wrote in her influential study The Body in Pain, although pain is a source of unmaking that robs the subject of language, the world is remade through artistic creation.3

Alison understood the inevitability of story, the way it functions to organize experience and beliefs.4 She recognized how those who have experienced pain or oppression use narrative to make and to remake an imperfect social world. Her work intersected with the project of narrative medicine in acknowledging the reparative power of telling stories and learning how to listen and interpret the stories of others.5

A particular concern in this book is how women use stories to organize their experiences of pregnancy and motherhood. Alison sees how the memoir can challenge well-known narratives about illness and disability, redefining what it means to live with physical and cognitive differences. In this book, Alison analyzes stories about disability, pregnancy, and motherhood but also tells stories of her own. For Alison, narrative at its best is the agent of complexity; in her evolving manuscript, she takes a complex approach, both as storyteller and as critic. Her primary commitment in this book is to understand the capacity of stories to work imaginative transformation that can have real-world consequences.

Throughout her research, she sought out and listened to a wide range of stories, told primarily by women. Alison’s method involved intensive listening punctuated by questions, comments, and affirmations. Her more finished work combines summary and analysis with long passages that allow the interviewees’ voices to come through directly. The interviews she had already completed represent a considerable diversity of perspectives on Down syndrome, including those from women who had abortions after a prenatal diagnosis and perspectives from parents of varied faith, class, and racial backgrounds at different stages of parenting. Much of that work is represented here.

With more time, Alison certainly would have thought further not just about the content of these narratives but also about their form. She was already beginning to ask about the affordances of memoir, why stories about the arrival and parenting of children with disabilities share a similar narrative arc, and the consequences of following different paths in telling stories about disability. She might well have spent time identifying the common features of women’s stories about prenatal and postnatal diagnoses and parenting children with disabilities. Among her unfinished work was an ongoing reflection on the formal similarities between stories told by women who terminated pregnancies after receiving a prenatal diagnosis and those who chose to continue. In trying to make sense of the accounts she had collected, Alison examined the common narrative devices women use to navigate the bewildering array of decisions around pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting. Eventually, she might also have considered the limits of personal stories as sources of knowledge and meaning. As the literary critic Amy Shuman asks, what are the possibilities and perils of using “other people’s stories” as the grounds for empathy and for moral action?6

If story is one link between Alison’s earlier and later visions of her project, the other is prediction. Alison’s research on prenatal diagnosis asks, in essence, what stories we bring to, and build from, predictive information. Her approach overlaps with queer critics who note the oppressive nature of a futurity organized around the expectation of heterosexual reproduction.7 Similarly, children with disabilities are often thwarted by predictions of a limited and unproductive future. They are described as “delayed” or “backward” to signal their deviation from the standard pace and developmental trajectory of more typical peers. A prenatal diagnosis may even more dramatically change how we imagine the future, usually by limiting or foreshortening our stories about the person a fetus may become. Alison asks how we understand the meaning of a future child’s arrival, whether that information is probabilistic (as in a screening test suggesting Down syndrome) or diagnostically certain (as in amniocentesis confirming the existence of Down syndrome). Even when the information is certain, what do we make of the ensuing uncertainties?

Alison approached the challenge of uncertain temporalities as a research question, but she also faced it in her own life. Despite a screening test suggesting an elevated likelihood that Maybelle had Down syndrome, she declined further testing. As a cancer patient, Alison faced a different kind of futurity, living through shocks and reprieves with every new battery of tests—each of which presented its own impossible mix of certainty and uncertainty, as in a prognosis of six to twelve months. Therefore, she understood the impact of prediction both as a parent and as a patient: MB, and my head. It seems likely that Alison’s later thoughts about the book’s direction were fueled by her life and that a scholarly monograph may have seemed insufficient to her embodied experience of the questions she considered.

* * *

In leaving us her manuscript and notes, Alison joins a group of important thinkers who left unfinished work for friends and colleagues to complete. At one point, Rachel collected a list that included such figures as the poet T. S. Eliot, author Ralph Ellison, and critics F. O. Matthiessen, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Edward Said, Raymond Williams, and Walter Benjamin. The company becomes more diverse with the inclusion of more recent authors like the poet Gary Fisher and cultural critics Chris Bell, Patricia Yaeger, Barbara Johnson, Lindon Barrett, Linda Singer, and William Hawkeswood.

We take a certain comfort in knowing that the challenges we face as editors have been shared by the editors and collaborators on these earlier projects. In Alison’s case, the inclusion of personal narrative presents us with special challenges: even as co-authors, we do not claim to speak for Alison; we hope that Alison speaks with our help. We are her assistive technology. In this role, we see a partial parallel with the work of parents who speak for their children—and the same ethical conundrums, the shadings of which are implied by prepositions: speaking for, speaking about, speaking over, speaking with. We have tried to speak with Alison or, rather, to let her speak through us—to preserve as much of her agency, her intentions, as we could. Paradoxically, to do so means alteration: collaborating with Alison requires a sort of editorial séance, a conjuring of the Alison we knew. Imagining her, to imagine whether she would approve of a particular change. Would she want this? Would she say this, and would she say this in this way?

In a short essay on writing, Eudora Welty describes the process of revision as driven by listening: she listens to an inner voice and trusts it to make her changes.8 As editors, we have taken the same approach, but the voice in our heads is Alison’s. Our work on this book is driven and shaped by our friendship with Alison; we have tried to listen to the voice on the page and to the voice we remember. The memory of that voice has been our surest editorial guide: Alison in conversation—her emphatic openness, her political fearlessness, her exuberant curiosity, her warmth and affection, her desire to connect and learn, to bear witness to life at its best and worst. (And, less obviously, to her privacy: Alison’s openness as a blogger and speaker belied how fiercely she guarded her own privacy and that of her family. We have honored the lacunae too.)

We first met to discuss our work on this project on a muggy day in New York City. There was so much to say in the time between the arrival of George’s train into the city and his return later that afternoon. We walked around Midtown, had lunch in a diner, walked some more, and drank some coffee as we tried to talk through what Alison had left us, what was missing, and what our process should be. At one point, we stopped to take a selfie. Neither of us looks great in the photo: the angle is unflattering, our hair is damp, and the sky behind us is a humid white. But afterward we confessed to each other that we felt Alison there with us, almost expecting that she might appear over our shoulders in the picture. In retrospect, our strong sense of Alison’s presence is less a spiritual intimation than it is a sign that the project we were starting would involve ongoing work of reviving, revisiting, and engaging with Alison’s desires, intentions, and beliefs. In choosing us to be her collaborators, she ensured that she would be present to us throughout the completion of this book.

Of course, our collaboration with Alison is different from working with a living co-author. Some of our constraints have been absolute. While Alison’s handwritten notes sometimes clearly signaled her intentions, at other times we couldn’t know for sure. She trusted us to carry the project forward, but trust is not license, so we’ve preferred a conservative approach. (This is probably the only time the word conservative has been publicly associated with Alison.) If we made structural changes, it was to bring like subjects together, rather than to formulate a new argument. If we made sentence edits, they were for clarity and concision, but we erred on the side of preserving Alison’s voice.

For this reason, we have favored finished work. Two chapters are built around published academic essays, and when assembling chapters from fragments, we have chosen the most polished pieces—nuggets, not raw ore. Wherever Alison appeared unsure of how to interpret or frame a certain chapter, or when her thinking was still developing, we have chosen what we thought was her best and most representative work. This approach was necessary in chapter 2, which is based on a long-running research project in which Alison conducted extensive interviews with women who either terminated fetuses with Down syndrome or carried them to term. In our view, the best treatment of this material was Alison’s article “The Inadequacy of ‘Choice’: Disability, Feminism, and Reproduction,” originally published in Feminist Studies. This article forms the basis of chapter 2. (We have also drawn on the transcript of a talk Alison gave at Columbia University on January 27, 2014, at a panel titled “Parenting, Narrative, and Our Genetic Futures.”) Though many more interview transcripts remain, the development and exploration of this raw material without Alison, who conceived of the project and conducted the interviews, would have been beyond our mandate.

Because Alison thought about the same subjects in many places and many arenas, it wasn’t uncommon for her to write about a topic such as prenatal diagnosis in blog posts, published articles, and interviews, as well as in handwritten notes. Where a passage clearly fit with an existing draft, we spliced it in. At the same time, we have made the invisible repairs customarily made by editors, streamlining sentences, line editing for clarity: where a sentence might be tightened without losing Alison’s voice, we did so. (George left in a few more adverbs than he otherwise might have, especially ones like incredibly, which expressed Alison’s verve and exuberance in life. She was incredibly excited to read things, to talk about them with her friends, to speak up about what she believed in. For Rachel, it was about preserving Alison’s optimism against her own tendency to see contradictions that complicate and undermine).

Early on, our friend Jordana Mendelson came up with the perfect metaphor for our process: the Japanese art of kintsugi, in which a broken vessel is fitted together, made whole again, using adhesive laced with gold. Kintsugi is a paradoxical art: by highlighting the jagged seams of the break, the technique holds wholeness and brokenness in a single artifact. In the same way, our own procedures, from this introduction to our individually authored chapters, footnotes, and occasional explanations in italics, are intended not to conceal but to call attention to the act of assembly.

Jordana’s insight began with a story Alison had told on her blog, about a favorite coffee mug. The front of the mug bore a cartoon of Princess Leia, holding a blaster and looking badass. Among her many enthusiasms, Alison was a Star Wars fan, and Princess Leia had special significance for her. (From May 2015: “She was a great example of a tough-talking, competent leader who just happened to be a woman. . . . In both my professional and personal life, I aspire to be more like her.”9) But in an essay published in the Charleston City Paper on June 2, 2016, Alison writes that the cup had fallen and broken:

She was gone, broken into five pieces. Drenched with hot coffee, I started to clean the floor. Several kitchen towels were required. And as I cleaned, I started crying. And I cried. I cried so much that I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t stop.

After several minutes, I finally knelt on the floor and softly, carefully, touched Princess Leia’s face. Her face is fierce. She holds a blaster, facing to the right but looking to the left, as if she has just noticed someone. On the other side of the cup, it reads “Don’t even think about touching my coffee, you stuck-up, half-witted, scruffy-looking nerf-herder!” The nerf-herder quote is from The Empire Strikes Back rather than the original Star Wars, but that doesn’t matter. There Princess Leia was, in my hands, broken but defiant.10

Alison explains that her brother has researched kintsugi online and that he and her husband would like to repair the cup. She then meditates on what a repair might mean, reflecting on irreversibility, illness, the body, and care:

I know they would spend far more than it was ever worth to have it put back together, to try and return Princess Leia to that moment before the cup shattered on the kitchen floor.

The point, though, isn’t for the coffee cup to be fixed, with its injuries rendered invisible. The point now is to recognize the beauty of the effort to mend what is broken, however imperfectly, however incompletely.

The old Princess Leia is gone, after 12 years and thousands of cups of coffee. My old body is gone as well, the result of age and illness. Neither the cup nor I can be made as good as new, and I won’t pretend otherwise.

There is value, though, in the effort—the expensive, difficult striving—to put together what has been broken. To honor what was lost, but also what has been gained. In even the failed repair, to see compassion in the work of both potter and physician.

A few weeks after Alison’s column, her repaired Princess Leia cup came back to her: art restorers had set aside the priceless museum artifacts they had been working on to do a rush kintsugi restoration of Alison’s mass-produced Star Wars coffee cup. On June 26, Alison announced the completed repair on her blog:

So many things have been challenging, as you all know.

Okay, the bad news is still the bad news. If you have read this blog, you know my diagnosis.

Today, though, I want to celebrate something wonderful. The Princess Leia coffee cup has been remade.11

Alison includes photographs, front and back, of the mended cup. Brian offers a postscript, thanking the craftspeople who did the repair. In retrospect, looking at that blog post, we notice its brevity, the changed proportion of photographs to text, and the postscript from Brian. All were indicators of the progress of Alison’s disease, of the exhaustion it brought and her increasing reliance on others to help her express herself.

We cannot think of a better metaphor for our work on this project than Jordana’s connection with the art of kintsugi. We are not creating a new product of our own; nor are we attempting to erase the seams between fragments. At the same time, we hope to do justice to the shape and purpose of the original design. Of course, every metaphor has its limits. While the term kintsugi is apt for the process of piecing this manuscript together, it also suggests a restored whole; the chapters here, by contrast, are present in this form for the first time. This book is a kintsugi of the future, an attempt to piece together what Alison did not have time to complete. It is also a synecdoche for loss, because our assembly only suggests what Alison might have achieved, had she had more time.

* * *

In her last weeks, Alison increasingly relied on others to speak. Emails came from family and friends. Sometimes they arrived dictated and jointly signed, like one from her mother, Kelly Piepmeier: Alison (via Kelly). We find the joint signature meaningful. It invokes care, motherhood, scholarly precision. It suggests that even in the worst things we face, the best of us is revealed; we draw on our histories together and our connections, and our mutual dependence comes to the fore. Another email, answering a query about the project, was sent by Alison’s dear and longtime friend Catherine Bush:

George,

This is Catherine again. Alison says, great!

And of course Alison also says . . .

love,

Alison

* * *

Early in 2013, Rachel sent both George and Alison an email:

Here’s my brainstorm idea: we do a three-way dialogue (for somewhere like DSQ [Disability Studies Quarterly]), framed as both a conversation about parenting, writing, and advocacy AND as a formal experiment in disability-inspired writing. Where the traditional essay is one author, one argument developed, we are experimenting with co-authorship and interdependent thought/writing. What do you think?

We did present a panel that year at the American Studies Association, but we did not have time to complete the writing project Rachel had suggested or the others we had hoped to do. In a way, this book has absorbed the impulse. It’s a continuation of our conversations, and as such, it suggests a second metaphor for our efforts: the idea of the welcome table that is the basis for chapter 3.

If kintsugi suggests the finished product—the book like a repaired cup, its seams deliberately made visible—the welcome table, a favorite metaphor of Alison’s, suggests what we hope to achieve. In its focus on conversation, interchange, and community, it suggests the process that, among other things, includes this book. The welcome table is an image of true community, a place where all are invited to gain sustenance while sitting together. For Alison, it is an image not only of the goal of activism and advocacy but also of the process: being “at the table,” as Alison writes, is shorthand for being represented and included. With all this in mind, the welcome table could be another metaphor for this book: a locus of conversation, where everyone is welcome as long as they come in a spirit of generosity and inclusion, where those who knew Alison can recall her presence, and where those who didn’t can glimpse the friend we lost. But more than that, we hope that others will take up and continue the work laid out here, that this book will be the beginning of a conversation and not the end.