Читать книгу The Lighthouse - Alison Moore - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE Violets

ОглавлениеFuth stands on the ferry deck, holding on to the cold railings with his soft hands. The wind pummels his body through his new anorak, deranges his thinning hair and brings tears to his eyes. It is summer and he was not expecting this. He has not been on a ferry since he was twelve, when he went abroad for the first time with his father. It was summer then too and the weather was just as rough so perhaps this should not be taking him by surprise.

His father took him to the ferry’s cinema. Futh does not remember what they saw. When they sat down, the lights were still up and there was no one else in there. He remembers having a bucket of warm popcorn on his lap. His father, smelling of the lager he had drunk beforehand at the bar, turned to Futh to say, ‘Your mother sold popcorn.’

She had been gone for almost a year by then, by the time Futh and his father took this holiday together. Mostly, she was not mentioned, and Futh longed for his father or anybody to say, ‘Your mother . . .’ so that his heart would lift. But then, when she was spoken about, she would invariably be spoiled in some way and he would wish that nothing had been said after all.

‘In those days,’ his father said, ‘the usherettes wore high heels as part of the uniform.’

Futh, shifting in his seat and burying his hand in his popcorn, hoped that the film or at least the trailers, even adverts, would start soon. Some people came in and sat down nearby, but his father went on just the same.

‘I was there on a date. The girl I was with didn’t want anything but I did. I went down the aisle to the front where your mother stood with her tray all lit up by the bulb inside. She sold me a bag of popcorn and agreed to meet me the following night.’

The lights went down and Futh, tensed in the dark auditorium, hoped that that would be it, that the story would end there.

His father leaned closer and lowered his voice. ‘I drove her up to the viewpoint,’ he said. ‘She had this very pale skin which glowed in the moonlight and I half-expected her to feel cold. She was warm though – it was my hands that were chilly.’

The screen lit up and Futh tried to focus on that, on the fanfare and the flicker of light on expectant faces, and his father said, ‘She complained about my cold hands but she didn’t stop me. She wasn’t uptight like some of the girls I’d taken up there.’

Futh felt the warm pressure of his father’s thigh against his own, felt the tickle of his father’s arm hairs on his own bare forearm, the heat of his father’s beery breath in his ear hole, his father’s hand reaching into his lap, taking popcorn. Finally, his father sat quietly back in his seat to watch the start of the film and after a few minutes Futh could tell by the sound of his breathing that his father had fallen asleep.

When his father woke up halfway through the film, he wanted to know what he had missed, but Futh, whose mind had been wandering, could not really tell him.

Ferries make Futh feel a bit sick. He becomes nauseous just thinking about walking through the bars and restaurants with their clashing textiles, sitting down at a dishcloth-damp table, the smell of other people’s warm food lingering beneath the tang of cleaning fluids, his stomach roiling. He prefers to be outside in the fresh air.

It is nippy though. He does not have enough layers on. He has not put a jumper in the overnight bag which is stowed between his feet. He has not packed a jumper at all. Waves smack the hull of the boat, splashes and salt smell flying up. He can feel the rumble of the engine, the vibrations underfoot. He looks up at the night sky, up towards the waxing moon, inhaling deeply through his nose as if he can catch its scent in the wind, as if he can feel its pull.

Now the ramp is being raised like a drawbridge. He is reminded of the closing leaves of a Venus flytrap, but this is slower and noisier.

The mooring ropes are dropped into the water and Futh, like a disconcerted train passenger unable to tell whether it is his or a neighbouring train which is pulling out of the station, sees the untethered land drawing away from him. The engine chugs and the water churns white between the dock and the outward bound ferry.

There is someone else up on the outer deck, on the far side of a life ring, a man wearing a raincoat and a hat. As Futh glances at him, the man’s hat blows off and lands in the sea, in their wake. The man turns and, noticing Futh, laughs and shouts something across the deck, against the wind. His words are lost but Futh gives an affable laugh in response. The man moves along the railings, holding on as if he might blow away as well. Arriving at Futh’s side, the man says, ‘Even so, I prefer to be outside.’

‘Yes,’ says Futh, catching the smell of the man’s supper coming from his mouth, ‘me too.’

‘I get a little . . .’ says the man, pressing the palm of his hand soothingly against his large stomach.

‘Yes,’ says Futh, ‘me too.’

‘I’m worse on aeroplanes.’

Futh and his companion stand and watch Harwich receding, the black sea rising and falling in the moonlight.

‘Are you on holiday?’ asks the man.

‘Yes,’ says Futh, ‘I’m going walking in Germany.’

When Futh tells the man that he will be walking at least fifteen miles a day for a week, doing almost a hundred miles in total, the man says, ‘You must be very fit.’

‘I should be,’ says Futh, ‘by the end of the week. I don’t walk much these days.’

The man reaches into the inside pocket of his coat, takes out a programme and hands it to Futh. ‘I’m on my way to a conference,’ he says, ‘in Utrecht.’

Futh glances at the programme before passing it back – carefully in the bluster – saying, ‘I don’t really believe in that sort of thing.’

‘No,’ says the man, putting it away again, ‘well, I’m undecided.’ He pauses before adding, ‘I’m also visiting my mother who lives in Utrecht. I’m dropping in on her first. I don’t get over very often. She’ll have been cooking all week, just for the two of us. You know how mothers are.’

Futh, watching the sea fill the growing gap between them and England, says, ‘Yes, of course.’

‘You’re just going for a week?’ says the man.

‘Yes,’ says Futh. ‘I go home on the Saturday.’

‘Same here,’ says the man. ‘I’ll have had enough by then, enough of her fussing around me and feeding me. I put on a couple of kilos every time I’m there.’

Futh puts his hand in his coat pocket, wrapping his fingers around his keycard. ‘I think I’m going to go to my room now,’ he says.

‘Well,’ says the man, pulling back his coat cuff to check the time, ‘it’s almost midnight.’ Futh admires the man’s smart watch and the man says, ‘It was a gift from my mother. I’ve told her she spends too much money on me.’

Futh looks at his own watch, a cheap one, a knock-off, which appears to be fast. He winds it back to just before midnight, back to the previous day. He says goodnight and turns away.

He is halfway across the deck when there is a tannoy announcement, a warning of winds of force six or seven, a caution not to risk going outside. He climbs down the steps, holding on to the handrail, and steadies himself against the walls until he reaches the door, which looks like an airlock. He goes through it into the lounge.

The floor is gently heaving. He feels it tilting and dropping away beneath him. He walks unsteadily across the room towards the stairs and goes down, looking for his level, following the signs pointing him down the corridors to his cabin.

He lets himself in with his keycard and closes the door behind him, putting his overnight bag down on a seat just inside. He takes off his coat and hangs it on a hook on the back of the door just above the fire action notice. It is a small cabin with not much more than the seat and a desk, a cupboard, bunk beds on the far side, and a shower room. There is no window, no porthole. He looks inside the cupboard, half-expecting a trouser press or a little fridge or a safe, finding empty hangers. He does not need a trouser press but he would quite like a drink, a continental beer. He opens the door to the shower room and finds a plastic-wrapped cup by the sink. He fills the cup from the tap and takes his drink over to the bunk beds. Switching on the wall-mounted bedside lamp and turning off the overhead light, he sits down on the bottom bunk to take off his shoes.

Peeling off his socks, he massages his feet, which are sore from walking around the ferry and standing so long, braced, on the outer deck. He once knew a girl who did reflexology, who could press on the sole of his foot with her thumbs knowing that here was his heart and here was his pelvis and here was his spleen and so on.

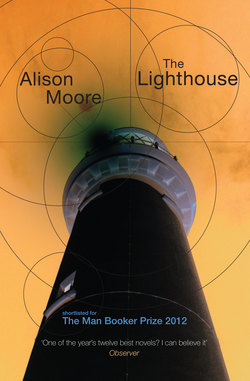

Standing again, he takes a small, silver lighthouse out of his trouser pocket and places it in a side pocket of his overnight bag where it will not roll around and get lost. He locates his travel clock, takes off his watch, and undresses. He has new pyjamas and buries his nose in the fabric, in the ‘new clothes’ smell of formaldehyde, before putting them on. Taking out his wash bag, he goes into the shower room.

He watches himself brushing his teeth in the mirror over the sink. He looks tired and pale. He has been drinking too much and not eating enough and sleeping badly. He cups his hands beneath the cold running water, rinses out his mouth and washes his face. When he straightens up again, reaching for a towel, water drips down the front of his pyjamas.

He imagines coming home, his reflection in the mirror on the return journey, his refreshed and tanned self after a week of walking and fresh air and sunshine, a week of good sausage and deep sleep.

Back in the bedroom, he climbs the little ladder up to the top bunk, gets in between the sheets and switches off the lamp. He lies on his back with the ceiling inches from his face and tries to think about something other than the rolling motion of the ferry. The mattress seems to swell and shift beneath him like a living creature. There is a vent in the ceiling, from which cold, stale air leaks. He turns onto his side, trying not to think about Angela, who is perhaps even now going through his things and putting them in boxes, sorting out what to keep and what to throw away. The ferry ploughs on across the North Sea, and home gets further and further away. The cold air from the vent seeps down the neck of his pyjama top and he turns over again. His heart feels like the raw meat it is. It feels like something peeled and bleeding. It feels the way it felt when his mother left.

‘I’m going home,’ she said, meaning New York, meaning three thousand miles away. It was only after she had gone that Futh realised she had not left an address. He looked on the pin board in the kitchen but all he found was the start of a shopping list, her handwriting an almost flat line, a dash of Biro, indecipherable.

He looked in the library for pictures of New York, finding skyscrapers with suns rising and setting in their mirrored windows and all lit up at night, the light reflected in the river.

On his father’s side, there was German, although his father had never been to Germany until they went there together when Futh was twelve. Futh’s granddad had left home young, could not get away quickly enough. He settled in England and did not see his parents or his brother again.

‘He never went home for a visit?’ asked Futh.

‘No,’ said his father. ‘He thought about it a lot, but he never made it home.’

Futh did not like to think that someone would just leave, and so abruptly, and never see their family again.

Abandoning the top bunk, Futh feels his way down the ladder to the bed underneath, and the cold air follows him.

He woke in the night and his mother was there, her round face above him, lit by the moon through a gap in the curtains. When she left his room he was alone in the dark with her scent – the smell of violets – and the sound of her footsteps going down the stairs.

By breakfast time, she was gone, and his father was already drunk. Before she left, his father never hit him. Afterwards, when he did, it was without warning, or nothing Futh noticed in time. It was like when birds flew into windows with a sudden sickening thud, and then having to look at the bird lying terribly still on the ground outside, perhaps only dazed but probably hurt or broken in some way.

Futh tried not to get under his father’s feet. Sometimes he stayed outside, sitting on top of his climbing frame until it was so dark he could not see the ground underneath, and the lawn could have been an ink-black lake or just a big nothing into which, jumping down, he would drop. He was safe out there – but in the darkness he could always see the bright square of the kitchen window.

Watching his father wandering around the kitchen, picking things out of the fridge and sniffing them, looking in the cupboards and opening a tin, lighting a hob, Futh would know when it was time to go in for supper. If he waited too long, the supper would go cold and everything would be spoilt. Or, watching his father sitting alone at a bare table, he would know to wait until his father went out before going in and putting himself to bed.

In the other direction, over the fence at the bottom of the garden, was Gloria’s house. Futh had been friends with Gloria’s son Kenny since the first year of junior school, even though they had little in common. Futh was not really a people person, while Kenny always had girls or a gang of boys around him. Kenny played football and army while Futh was in the school library waiting for breaktime to end. Kenny went orienteering with his father, and could build a bike from scratch. When Futh took his own bike apart and could not put it back together again his father refused to help. In the end, Futh put all the bits – the gears and the chain and the pedals and so on – into a box in the shed and kept them there thinking that one day he would know how to do it.

Kenny and Futh used to stand at their bedroom windows at lights out, facing one another across their back gardens, each with a torch, flashing messages through the darkness. It was like Morse code except that it didn’t mean anything. Kenny would flash-flash-flash and Futh would flash-flash-flash back; Kenny would flash-pause-flash and Futh would send it back. Eventually, the game would stop. It was, for Futh, like looking at a lighthouse on the horizon at night. There was this flashing of light and then nothing, and you waited for the next flash, looking at where the light had been and where it would be again but you were looking at darkness.

When eventually no flash of light interrupted the darkness, it meant that Kenny was in bed, and then Futh got into bed too. In later years he would take the torch under the covers with him and read the sometime banned literature from his mother’s bookshelves.

Halfway through junior school, Kenny left – his father moved out and Kenny went with him. It happened suddenly, with nobody telling Futh that Kenny was going or that he had gone, and Futh spent some nights at his bedroom window waiting to see Kenny’s torch, wielding his own, flash-flash-flash, like a mating signal, receiving no reply.

Futh did not see Kenny again until Christmas. They met at the butcher’s. Gloria, coming into the shop and standing in line behind Futh and his mother, said hello. Kenny had already gone to wait outside and Futh joined him. Futh asked Kenny why he had left, and Kenny looked at him as if he were stupid and said, ‘I went with my dad.’

‘But why did your dad leave?’ asked Futh.

‘Well, he couldn’t stay,’ said Kenny, ‘knowing about the affair, could he?’

When primary school ended and Futh’s mother left and Futh began to spend his free time sitting on his climbing frame in the dark, he found himself thinking about Kenny, whom he had not seen in the two years since their meeting at the butcher’s. He looked at Kenny’s empty bedroom window, underneath which Gloria ate her supper alone in the kitchen.

She never seemed to have friends over, female friends like his mother had, who used to gather in the living room or on the patio in good weather, and sometimes his mother played a favourite song, her favourite singer, and started dancing, while he played by himself nearby, told to stay out of the way, getting as close as he dared, mesmerised by the noise and the perfume and the minidressed legs of his mother’s friends. Gloria had not been one of them.

He got to know Gloria’s habits. When she came into the kitchen to prepare her evening meal, she would turn on the radio. She would open the back door to call in the cat and feed it titbits from her plate while she was eating. When she finished, she would clear up and then, leaving the radio on, she would go upstairs to take a shower or a bath, and he would see her, the vague pinkness of her, fragmented by the bathroom window’s bobbled glass. She would come back down in her nightie, sit at the kitchen table and have a drink or two. She would feed the cat again, maybe take out the rubbish, or, in that summer of drought, soak her garden with the hosepipe in the dark. Alone in a street full of parched and pale lawns, while neighbours’ plants wilted and died, Gloria’s garden was lush.

The back door opened and Gloria appeared on her doorstep with a rubbish bag, but instead of going to the bins she walked onto the lawn, coming his way in her nightie, bringing the rubbish bag with her.

Leaning against the fence, she said, ‘All on your lonesome?’

Not knowing what to say, Futh said nothing.

‘Me too,’ she said, twirling the rubbish bag in her hand. ‘I could do with some company.’

‘I’ve got to go in soon,’ said Futh.

Gloria looked over Futh’s shoulder at the house, at the lit kitchen window. ‘What you and your daddy need now,’ she said, ‘is a nice holiday. That’s what I did when my husband left me. I went off on holiday. After a fortnight of sunshine and cocktails, I wasn’t even thinking about him.’

Futh, hearing his father calling him, turned around and was beckoned inside. When Futh turned back, Gloria was already walking away with her rubbish bag.

‘What did she want?’ asked his father, as Futh stepped into the kitchen.

‘She just came over to talk to me,’ said Futh.

‘What did she say?’

‘She said she was lonely.’

‘I don’t want you talking to her,’ said his father.

There were bowls of oxtail soup on the table. They sat down and ate, and Futh, through the curtainless window and across the dark back gardens, saw Gloria’s kitchen light and all her downstairs lights go off. A minute later, he saw her bathroom light go on again.

There was a curtain rail there, above the kitchen window. When they moved into this house, when Futh was seven, his mother had measured up for curtains, but she never got round to making them before she left. She had planned to paint the house from top to bottom, but had only done the landing when she stopped and did no more. Most of the pictures she brought from the old house were never hung, and the flowerbeds were planted but then grew wild.

His father, polishing off his oxtail soup, standing and reaching for his slip-on shoes, said, ‘I’m going out. Finish up, it’s your bedtime.’ When he opened the kitchen door, the cold night air came in and stayed when he was gone.

Gloria’s bathroom light went off and Futh saw Gloria coming into her bedroom. He shovelled his soup, chasing the last bits of meat around the bottom of the bowl. He saw her in front of her dressing table mirror, checking the look of herself in her nightie, touching her hair. She went back out onto the landing. A moment later, the light in the downstairs hallway went on, and when it went off again Futh stood quickly, put his empty soup bowl in the sink and went to bed.

He wakes in darkness. He can’t see a thing and doesn’t know where he is.

‘Where am I?’ he asks, before grasping that he is alone. He thinks he must be in the spare room, but everything feels wrong. Then he thinks he might be in his second-hand bed at the new flat but that does not seem right either. Finally he realises that he is on the ferry. He is on holiday, he thinks, that’s all, he is going on holiday, and he goes back to sleep.

He and his father had a daytime crossing to Europe. As well as taking him to the cinema and letting him have popcorn, his father bought him sweets in a mug from the duty-free shop and too many packets of peanuts at the bar and Futh felt sick in the car all the way from the ferry to their hotel in Germany.

Their hotel room had two single beds and a small bathroom. At bedtime, when Futh wanted a night light, his father put the bathroom light on and left the door ajar, and then said, ‘Go to sleep now.’ But Futh lay awake, turned towards that crack of light, watching in the big mirror behind the sink as his father changed his shirt and combed his hair and brushed his teeth and then – Futh quickly closing his eyes and trying to breathe like someone sleeping – he left, the door clicking shut behind him.

In the morning, his father would be there, in the other single bed, dozing with his mouth open, the odour of alcohol seeping out. When Futh got out of bed to go to the bathroom, his father would stir, asking, with eyes narrowed against the daylight, what time it was. Futh would tell him, and his father would be surprised by how late it was. He would say to Futh, ‘You slept well.’ And Futh would say nothing about when, disturbed in the early hours, he saw the bedroom door opening, the light coming in from the corridor, his father returning with a woman, a different woman every night. When the door shut behind them, his father and these women felt their way through the bedroom still dimly lit by the light from the bathroom into which his father took them, the bathroom light briefly flooding the bedroom before the door was again closed leaving only the narrow gap through which Futh watched them in the mirror. And Futh, who had not slept well, stood in the bathroom in the morning, not wanting to touch the sink area, not wanting to look in the mirror.

He said nothing to his father about having woken up to find himself wetting the bed. He pulled his blanket over the wet sheets and got ready to go out, knowing that it would all be made clean in his absence.

Futh opens his eyes in the dark and hears a woman speaking to him loudly in a language he does not understand. He squints in the direction of his travel clock, trying to make sense of the position of the luminous hands. He can’t see the underside of the bunk right above him, and he reaches out and touches it to reassure himself that he is where he thinks he is. Then, feeling for the switch on the wall, he turns on the light.

It is morning and the ferry is arriving into the Hook of Holland. Futh gets up.

In the shower, in an apple-scented lather, he thinks about Angela. He wonders what she did with her Friday night and what she is planning to do with her Saturday. They have spent most of their Friday evenings on the sofa watching television. Now, early on a Saturday morning, he imagines her barely home from a night out, or in bed asleep, or not asleep, with another man. It is more than fifteen years since he was with anyone else.

Turning off the shower and stepping out of the cubicle onto the non-slip floor, he finds himself still thinking about his father and the women in the hotel bathroom. He leans against the sink area, wipes his hand over the steamed-up mirror and looks again at his reflection. He does not see his father in himself.

Back in the bedroom, he dresses, returning the silver lighthouse to his trouser pocket. He goes around collecting up the complimentary items – a Biro, sachets of coffee and sugar and individual portions of UHT milk, the remaining toiletry miniatures, a shower cap, the plastic cup – and packs them in his overnight bag. He can make use of all these things in his new flat.

He leaves his cabin, taking his bag and his anorak with him, not wanting to have to come back. He goes to look for some breakfast, but when he is standing at the edge of the restaurant, eyeing the queue and smelling the warm egg, the warm meat, he changes his mind. Instead, putting on his anorak and shouldering his bag, he heads for the outer deck.

It has been raining and is still raining behind them, mizzling into the sea. The metal steps are slippery and he has to go carefully. The sky overhead is a pale grey but it is clearing up over Holland as they draw near. He stands with his hands on the wet railings, watching the ferry’s arrival into the Dutch terminal, and on the other side of the deck, the man in the raincoat who lost his hat does the same.

Futh moves his watch on an hour. Now he will go down to the car deck. When he is waved forward, he will drive out onto the continent, behind the wheel in another country for the first time.

‘Not long now.’

Futh turns and finds the man standing beside him.

‘Where in Germany are you going?’ asks the man.

‘Hellhaus,’ says Futh. ‘Near Koblenz. It’s quite a long drive.’

‘Oh, it won’t take you long,’ says the man. ‘A few hours.’

‘If I don’t go wrong,’ says Futh, picturing the pristine European road atlas on his passenger seat. Angela has always done the long-distance driving and is also the better navigator.

The ferry is docking. ‘We should head down to the car deck,’ says Futh.

‘I’m on foot,’ says the man.

‘Where did you say you’re going?’

‘Utrecht. It’s not far from here. You’ll go right past it on your way to Koblenz. You should stop there for coffee if you have time.’

Futh looks at the man’s damp coat, smells the rain trapped in its weave. He looks at the residue of rain on the man’s eyelashes, on his eyebrows, on his bare head. He imagines this man in his passenger seat, reading the map and knowing the roads. He says, ‘Would you like a lift to Utrecht?’

The man beams. ‘Well,’ he says, ‘if you’re going there anyway, that would be very kind. You can have coffee at my mother’s house.’

‘I’d like that,’ says Futh, ‘very much.’

The man holds out his hand and says, ‘Carl.’

Carl’s hand is big and tanned and, Futh finds as he takes it, warm. Futh’s own hand – slim and pale and cold – seems lost inside it. ‘Futh,’ he says in reply. Carl leans closer, turning one ear towards him as if he has not quite caught it, and Futh has to say again, ‘Futh.’

The two men turn away from the railings to head inside together. The boat’s wet surfaces gleam in the early morning sunlight, and Futh wonders how long the ferry will stay in the brightening port before turning around and going out again, back out into the cold, grey sea.