Читать книгу The Golden Gate - Alistair MacLean, Alistair MacLean, John Denis - Страница 8

THREE

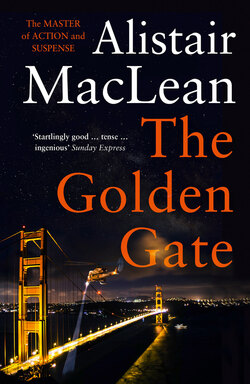

ОглавлениеThe Golden Gate Bridge is unquestionably one of the engineering wonders of the world. To San Franciscans, inevitably, it is the engineering wonder of the world and as bridges go it must be at once the most spectacular and graceful in existence. To see the two great brick-red – or orange or ochre, according to the quality of the light-towers emerging from the dense banks of fog that so frequently billow in from the Pacific is to experience a profound sense of unreality and when the fog disperses completely the feeling changes to one of disbelief and a benumbment of the senses that men had not only the audacity to conceive of this epic poem in mechanical grandeur but also the technical expertise to bring it into being. Even while the evidence of the eyes is irrefutable it still remains difficult for the mind to accept that it actually is there.

That it is there at all is not, in fact, due to man but to one man, a certain Joseph B. Strauss, who, in the pig-headed fashion of considerable Americans, despite seemingly unsurmountable and political difficulties and the assurances of his architectural colleagues that his dream was a technical impossibility, just went ahead and built it anyway. The bridge was opened in May 1937.

Until the construction of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge in 1964, it was the longest single-span suspension bridge in the world. Even now, it is only about twenty yards shorter. The two massive towers that support the bridge soar seven hundred and fifty feet above the waters of the Golden Gate: the bridge’s total length is just under one and three-quarter miles. The cost of construction was $35,000,000: to replace it today something in the region of $200,000,000 would be needed.

The one sombre aspect about the bridge is that for Americans who find the burdens of life intolerable to bear this is unquestionably the most favoured point of departure. There have been at least five hundred known suicides: probably as many again have gone undetected. There have been eight known survivors. Among the rest, the possibility of survival seems extremely remote. If any did indeed survive the shattering impact of the two-hundred-foot drop to the water, the surging tides and vicious currents of the Golden Gate would swiftly have completed what the jump itself failed to do. Those dangerous tides and currents make their effect felt for some distance on either side of the bridge. Three miles to the east lies what used to be the forbidding prison-fortress of Alcatraz Island. No precise figures of those who attempted escape by swimming are available: but it is believed that only three of those who tried it ever survived.

It is idle to speculate upon the choice of the bridge as a springboard to eternity. Psychiatrists would have it that it is a spectacular and attention-riveting finale to a drab and unspectacular life dragged out in a grey anonymity. But it would seem that there is nothing either eye-catching or spectacular in jumping into the darkness in the middle of the night.

The procession made its stately way under the first of the giant towers. In the upholstered luxury of the Presidential coach, the King, Prince and their two oil ministers gazed around them with a carefully controlled degree of regal and viceregal appreciation, for although there was a marked absence of Golden Gate Bridges in their dusty homelands – and, indeed, no need for them – it would not have done to admit that there were some things better done in the West than in the Middle East. Nor did they enthuse overmuch about the scenery, for although a million square miles of drifting sands might not be without its attractions for a homesick Bedouin, it could hardly be said to compare with the lush and fertile greenery of the farm land and forest land that stretched ahead of them across the Golden Gate. Indeed, the whole of the Bay Area could not have looked better than it did on that splendid June morning, with the sun already climbing high to their right in a cloudless sky and sparkling iridescently off the blue-green waters below. It was the perfect story-book setting for a day which, the President and Hansen, his energy czar, devoutly hoped would have a story-book ending.

The Prince looked around the coach, this time in open admiration, for he was very much a man of his own generation and possessed of a passion for all things mechanical and said in his clipped Oxford accent: ‘My word, Mr President, you do know how to travel in style. I wish I had one of those.’

‘And so you shall,’ the President said indulgently. ‘My country would be honoured to present you with one, as soon as you return to your homeland. Equipped to your own specifications, of course.’

The King said drily: ‘The Prince is accustomed to ordering his vehicles by the round dozen. No doubt, Achmed, you would like a couple of those to go with it.’ He pointed upwards to where two naval helicopters were hovering overhead. ‘You do take good care of us, Mr President.’

The President smiled non-committally. How could one comment upon the obvious? General Cartland said: ‘For decorative purposes only, your Highness. Apart from your own security men waiting on the other side and an occasional police car, you will see nothing between here and San Rafael. But the security is there all the same. Between here and San Rafael the motorcade will be under heavily armed surveillance literally every yard of the way. There are crackpots everywhere, even in the United States.’

‘Especially in the United States,’ the President said darkly.

In mock seriousness the King said: ‘So we are safe?’

The President regained his smiling composure. ‘As in the vaults of Fort Knox.’

It was at this point, just after the lead coach had passed the halfway mark across the bridge, that five things happened in almost bewilderingly rapid succession. In the rear coach Branson pressed a button on the console in front of him. Two seconds later a small explosion occurred in the front of the lead coach, almost beneath the driver’s feet. Although unhurt, the driver was momentarily shocked, then swore, recovered quickly and jammed his foot on the brake pedal. Nothing happened.

‘Sweet Jesus!’ It took him all of another second to realize that his hydraulic lines were gone. He jammed his handbrake into the locked position and changed down into first gear. The coach began to slow.

Branson abruptly lifted his right arm, as abruptly lowered it again to reinforce the left in bracing himself against the fascia. Behind him his men did the same, outstretched arms, slightly bent at the elbows as they had learnt in frequent practices, braced against the backs of the seats in front: nobody sat in the front seats. Van Effen slipped the gear into neutral and kicked down on the brake pedal as if he were trying to thrust it through the floor.

The fact that Van Effen had recently and with malice aforethought seen fit to deactivate his rear brake lights did little to help the plight of the hapless driver of the police car behind. The motorcade was travelling slowly, about twenty-five miles an hour, and the rear police car was trailing the coach by about the same number of feet. The driver had no reason to suspect that anything might be amiss, for the bridge was closed to all traffic except the motorcade: there was no earthly reason to expect anything should interfere with the smooth and even tempo of their progress. He may even have spared a momentary side glance to admire the view. However it was, when he first realized that all was not what it should have been the distance between them had halved. An incredulous double-take cost him another few feet and, skilled police driver though he was, his reactions were no faster than those of the next man and by the time his foot had hit the brake the gap between himself and the now stationary coach had lessened to not more than five feet. The effect of a car’s striking a solid and immovable object at twenty miles an hour has a less than humorous effect on the occupants of that car: the four officers in the car were no exception.

At the moment of impact Branson touched a second button on the fascia. The lead coach, slowing only by its handbrake, was now doing no more than ten miles an hour when another small explosion occurred in the drinks cabinet at the rear, an explosion followed immediately by a pronounced hissing as if caused by compressed air escaping under very high pressure. Within seconds the entire compartment was filled with a dense, grey, obnoxious and noxious gas. The coach, almost immediately out of control as the driver slumped forward over the wheel, slewed slowly to the right and came to a rest less than two feet from the side of the road. Not that it would have mattered particularly if it had struck the safety barriers on the side of the bridge which were of a nature to withstand the assaults of anything less than a Chieftain tank.

The Presidential coach came to no harm. The driver had seen the lead coach’s brake warning lights come on, braked, pulled left to avoid the slewing coach ahead and came to a rest beside it. The expressions of the twelve occupants of the coach expressed varying degrees of unhappiness but not, as yet, of alarm.

The police car and two motor-cycle outriders leading the motorcade had been curiously slow to observe the confusion behind them. Only now had they spotted the slewed coach and were beginning to turn.

In the rear coach everything was taking place with the clockwork precision that stemmed from a score of practice runs that had covered all conceivable potentialities. Van Effen jumped down from the left-hand door, Yonnie from the right, just as the two motor-cycle outriders pulled up almost alongside. Van Effen said: ‘You better get in there fast. Looks like we got a stiff on our hands.’

The two patrolmen propped their machines and jumped aboard the coach. They could now no longer be seen by the returning lead police car and outriders so it was safe to take swift and efficient action against them, which was done with considerable ease not least because their attention had immediately been caught up by the sight of the bound figure lying sprawled on the floor in the rear aisle.

Seven men emerged swiftly from the doors of the coach. Five of those joined Van Effen and Yonnie and ran towards the other coaches. Two more ran back towards the crashed police car. Two others inside the coach swung wide the rear door and mounted what appeared to be a relatively harmless length of steel tubing on a tripod stand. Branson and Jensen remained where they were: the bound man on the floor, whose identity Jensen had taken over, regarded them all severally with a baleful expression but, beyond that, the options open to him were rather limited.

The two men who had run back towards the crashed police car were called Kowalski and Peters. They didn’t look like criminals, unless a couple of prosperous young commuters from the stockbroker belt could be called criminals. Yonnie apart, none of Branson’s associates bore any resemblance whatever to the popular concept of those who habitually stepped outside the law. Both men, in fact, had killed a number of times, but then only legally – as far as the term ‘legal’ could be interpreted – as members of a highly specialized Marine commando unit in Vietnam. Disillusioned with civilian life they’d found their next best panacea with Branson, who had a splendid eye for the recruitment of such men. They had not killed since. Branson approved of violence if and when necessary: killing was not permitted except as a last resort. In his thirteen years of upsetting law officers in the United States, Canada and Mexico, Branson had not yet had to have recourse to the last resort. Whether this was due to moral scruples or not was unclear: what was clear was that Branson regarded it as bad business. The degree of intensity of police efforts to catch robbers as opposed to murderers differed quite appreciably.

The windows of both front doors of the car were wound down – obviously they had been so at the moment of the crash. The four uniformed men seated inside had not been seriously injured but clearly had been badly shaken and had suffered minor damage, the worst of which appeared to be a broken nose sustained by the man in the front seat next to the driver. For the most part they were just dazed, too dazed, in any event, to offer any resistance to the removal of their weapons. Working in smooth unison Kowalski and Peters wound up the front windows. Peters closed his door while Kowalski threw in a gas bomb and closed his in turn.

None of any of this action had been witnessed by the returning police car’s crew or the motorcycle outriders. The policemen left their car and machines and were cautiously approaching the lead coach when Yonnie and Van Effen with the five others came running up. All had guns of one kind or another in their hands.

‘Quickly!’ Van Effen shouted. ‘Take cover! There are a couple of crazy bastards back in that coach there, one with a bazooka, the other with a Schmeisser. Get behind the bus!’

Given time to consider the matter the policemen might have queried Van Effen’s statements but they weren’t given the time and the instinct for immediate if irrational self-preservation remains always paramount. Van Effen checked quickly to see if they were hidden from the view of the Presidential coach. They were. Not that he feared anything from that source, he just wanted to be spared the chore of blasting open the lock of the door that would be surely locked against them if their actions were observed.

He nodded to Yonnie and walked away with another man towards the rear of the bus. Whatever might be said, and had unkindly been said, about Yonnie’s cerebral limitations, this was the situation he had been born for, a basically elemental one in which action took precedence over thoughts. Long training had even given the vocabulary appropriate to the occasion. He said: ‘Let’s kinda put our hands up, huh?’

The six men turned round. Their expressions ran through the gamut of astonishment, anger and then resignation. Resignation was all that was left them. They had, with reason enough, not yet thought it time to produce their own weapons, and when the wise man is confronted at point-blank range with a pair of submachine-pistols he does what he is told and just kinda puts his hands up. Yonnie kept them covered while another man relieved them of their pistols. The remaining two men began to run back towards the rear coach as soon as they saw Van Effen and another climb aboard the Presidential coach.

The reaction of those aboard this coach had, so far, amounted to no more than an amalgam of perplexity and annoyance, and even that was slight enough. One or two were making the customary laborious effort to rise when Van Effen mounted the steps.

‘Please relax, gentlemen,’ he said. ‘Just a slight delay’ Such is the authority of even a white coat — in a street accident a crowd will make way for a man in a butcher’s apron – that everybody subsided. Van Effen produced an unpleasant-looking weapon, a double-barrelled 12-bore shotgun with most of the barrel and stock removed to make for easier transport, if not accuracy. ‘I am afraid this is what you might call a hold-up or hijack or kidnap. I don’t suppose it matters very much what you call it. Just please remain where you are.’

‘Good God in heaven!’ The President stared at Van Effen’s moonface as if he were a creature from outer space. His eyes, as if drawn magnetically, went to the King and the Prince, then he returned his incredulous, outraged gaze to Van Effen. ‘Are you insane? Don’t you know who I am? Don’t you know you’re pointing a gun at the President of the United States?’

‘I know. You can’t help being what you are any more than I can help being what I am. As for pointing guns at Presidents, it’s a long if not very honourable tradition in our country. Please do not give any trouble.’ Van Effen looked directly at General Cartland – he’d had him under indirect observation from the moment he had entered the coach. ‘General, it is known that you always carry a gun. Please let me have it. Please do not be clever. Your .22 can be nasty enough if it is accurate enough: this whippet will blast a hole the size of your hand through your chest. You are not the man, I know, to confuse courage with suicide.’

Cartland smiled faintly, nodded, produced a small, black, narrow automatic and handed it across.

Van Effen said: Thank you. I’m afraid you will have to remain seated for the moment at least. You have only my word for it, but if you offer no violence you will receive none.’

A profound silence descended. The King, eyes closed and hands folded across his chest, appeared to be communing either with himself or with the All-powerful. Suddenly he opened his eyes, looked at the President and said: ‘Just how safe are the vaults in Fort Knox?’

‘You’d better believe me, Hendrix,’ Branson said. He was talking into a hand-held microphone. ‘We have the President, the King and the Prince. If you will wait a minute or two I’ll have the President himself confirm that to you. Meantime, please don’t attempt anything so stupid or rash as to try to approach us. Let me give you a demonstration. I assume you have some patrol cars near the south entrance and you are in radio contact with them?’

Hendrix didn’t look like anyone’s conception of a Chief of Police. He looked like a professorial refugee from the campus of the nearby university. He was tall, slender, dark, slightly stooped and invariably immaculately groomed and conservatively dressed. A great number of people temporarily or permanently deprived of their freedom would have freely if blasphemously attested to the fact that he was very very intelligent indeed. There was no more brilliant or brilliantly effective policeman in the country. At that moment, however, that fine intelligence was in temporary abeyance. He felt stunned and had about him the look of a man who has just seen all his nightmares come true.

He said: ‘I am.’

‘Very well. Wait.’

Branson turned and made a signal to the two men at the rear of the coach. There was a sudden explosive whoosh from the recoilless missile weapon mounted at the rear. Three seconds later a cloud of dense grey smoke erupted between the pylons of the south tower. Branson spoke into the microphone. ‘Well?’

‘Some kind of explosion,’ Hendrix said. His voice was remarkably steady. ‘Lots of smoke, if it is smoke.’

‘A nerve gas. Not permanently damaging, but incapacitating. Takes about ten minutes’ time before it oxidizes. If we have to use it and a breeze comes up from the north-west, north or northeast – well, it will be your responsibility, you understand.’

‘I understand.’

‘Conventional gas-masks are useless against it. Do you understand that also?’

‘I understand.’

‘We have a similar weapon covering the northern end of the bridge. You will inform police squads and units of the armed forces of the inadvisability of attempting to move out on to the bridge. You understand that too?’ ‘Yes.’

‘You will have been informed of the presence of two naval helicopters hovering over the bridge?’

‘Yes.’ The rather hunted look had left Hendrix’s face and his mind was clearly back into top gear. ‘I find it rather puzzling, I must say.’

‘It needn’t be. They are in our hands. Have an immediate alarm put through to all local army and naval air commanders. Tell them if any attempt is made to dispatch fighters to shoot down those helicopters they will have very unpleasant effects on the President and his friends. Tell them that we shall know immediately whenever any such plane does lift off. The Mount Tamalpais radar stations are in our hands.’

‘Good God!’ Hendrix was back to square one.

‘He won’t help. They are manned by competent radar operators. No attempt will be made to retake those stations whether by land or airborne assault. If such an assault is made we are aware that we have no means of preventing it. However, I do not think that the President, King or Prince would look kindly upon any individual who was responsible for depriving them of, say, their right ears. Please do not think that I am not serious. We shall deliver them, by hand, in a sealed plastic bag.’

‘No such attempt will be made.’ Captain Campbell, a burly, sandy-haired, red-faced and normally jovial character whom Hendrix regarded as his right-hand man, regarded Hendrix with some surprise, not because of what he had just said but because it was the first time he had ever seen Hendrix with beads of sweat on his brow. In an unconscious gesture Campbell reached up and touched his own forehead, then looked with a feeling of grave disquiet at the dampened back of his hand.

Branson said: ‘I hope you mean what you say. I will contact you shortly.’

‘It will be in order if I come down to the bridge? It would appear that I have to set up some kind of communications headquarters and that seems the most logical place for it to be.’

‘That will be in order. But do not move out on to the bridge. And please prevent any private cars from entering the Presidio. Violence is the very last thing we want but if some arises I do not wish innocent people to suffer.’

‘You are very considerate.’ Hendrix sounded, perhaps justifiably, more than a little bitter.

Branson smiled and replaced the microphone.

The gas inside the lead coach had vanished but the effect it had had on the occupants had not. All were still profoundly unconscious. Some two or three had fallen into the aisle without, apparently, having sustained any injuries in the process. For the most part, however, they just remained slumped in their seats or had fallen forward against the backs of the seats in front of them.

Yonnie and Bartlett moved among them but not in the capacity of ministering angels. Bartlett, at twenty-six, was the youngest of Branson’s men, and looked every inch a fresh-faced college boy which he every inch was not. They were searching every person in the coach, and searching them very thoroughly indeed, those who were being subjected to this indignity being in no position to object. The lady journalists were spared this but their handbags were meticulously examined. It said much for the standards that Branson imposed that none of the several thousand dollars that passed through the hands of Yonnie and Bartlett found its way into either of their pockets. Robbery on a grand scale was big business: robbery on a small scale was petty larceny and not to be tolerated. In any event, they weren’t looking for money, they were looking for guns. Branson had reasoned, and correctly as it turned out, that there would be several special agents in the journalists’ coach, whose assignment would be not the direct protection of the President and his guests but the surveillance of the journalists themselves. Because of the worldwide interest aroused by the visit of the Arabian oil princes to the United States, at least ten of those journalists aboard were from abroad – four from Europe, the same from the Gulf States and one each from Nigeria and Venezuela, countries which might well be regarded as having a pressing interest in any transactions between the major oil states and the United States.

They found three such guns and pocketed them. The three owners of the guns were handcuffed and left where they were. Yonnie and Bartlett descended and joined the man who was guarding the six still largely uncomprehending policemen who were handcuffed together in single file. Another man was seated behind one of the bazooka-like missile firers that was guarding the north tower. Here, as at the southern end, everything was completely under control, everything had gone precisely as Branson had meticulously and with much labour planned over the preceding months. Branson had every reason to be feeling agreeably pleased with himself.

Branson, as he stepped down from the rear coach, looked neither pleased nor displeased. Things had gone as he had expected them to and that was that. His followers had often remarked, although never in his hearing, on Branson’s almost staggering self-confidence: on the other hand they had to admit that he had never, as yet, failed to justify his utter trust in himself. Of Branson’s permanent nucleus of eighteen men, nine of them had spent various times in various penitentiaries up and down the country reflecting upon the vagaries of fortune. But that was before they had been recruited by Branson. Since then not one of the eighteen had even got as far as a courtroom far less the prison walls: when it was taken into account that those included such semi-permanent guests of the United States Government as Parker this record could be regarded as an achievement of no little note.

Branson walked forward to the Presidential coach. Van Effen was standing in the doorway. Branson said: ‘I’m moving the lead coach ahead a bit. Tell your driver to follow me.’

He moved into the lead coach and with Yonnie’s help dragged clear the slumped driver behind the wheel. He slid into the vacant seat, started the engine, engaged gear, straightened out the coach and eased it forward for a distance of about fifty yards, bringing it to a halt with the use of the handbrake. The Presidential coach followed, pulling up only feet behind them.

Branson descended and walked back in the direction of the south tower. When he came to the precise middle of the bridge – the point at which the enormous suspension cables were at their lowest – he looked behind him and again in front of him. The fifty yards of the most central section of the bridge, the section where the helicopter rotors would be most unlikely to be fouled by the cables, even if subjected to the unseen and unforeseen vagaries of wind, was clear. Branson walked clear of the area and waved to the two machines chattering overhead. Johnson and Bradley brought their naval helicopters down easily and with the minimum of fuss. For the first time in its long and august history the Golden Gate Bridge was in use as a helipad.

Branson boarded the Presidential coach. Everyone there was instinctively aware that he was the leader of the kidnappers, the man behind their present troubles, and their reception of him did not even begin to border on the cordial. The four oil men and Cartland looked at him impassively: Hansen, understandably, was more jittery and nervous than ever, his hands and eyes forever on the rapid and almost furtive move: Muir was his usual somnolent self, his eyes half-closed as if he were on the verge of dropping off to sleep: Mayor Morrison, who had won so many medals in the Second World War that he could scarcely have found room for them even on his massive chest, was just plain furious: and so, indisputably, was the President: that expression of kindly tolerance and compassionate wisdom which had endeared him to the hearts of millions had for the moment been tucked away in the deep freeze.

Branson said without preamble but pleasantly enough: ‘My name is Branson. Morning, Mr President. Your Highnesses, I would like -’

‘You would like!’ The President was icily angry but he had the expression on his face and the tone in his voice under control: you don’t have two hundred million people call you President and behave like an unhinged rock star. ‘I suggest we dispense with the charade, with the hypocrisy of empty politeness. Who are you, sir?’

‘I told you. Branson. And I see no reason why the normal courtesies of life should not be observed. It would be pleasant if we were to begin our relationship – an enforced introduction on your side, I agree – on a calmer and more reasonable basis. It would make things so much more pleasant if we behaved in a more civilized fashion.’

‘Civilized?’ The President stared at him in a genuine astonishment that swiftly regressed to his former fury. ‘You! A person like you. A thug! A crook! A hoodlum! A common criminal. And you dare suggest we behave in a more civilized fashion.’

‘A thug? No. A crook? Yes. A hoodlum? No. A common criminal? No. I’m a most uncommon criminal. However, I’m not sorry you adopt this attitude. Having you express yourself with such hostility to me doesn’t mean that it eases my conscience in what I may have to do to you. I don’t have any conscience. But it makes life that much simpler for me. Not having to hold your hand – I don’t speak literally, you understand-makes it all that much easier for me to achieve my ends.’

‘I don’t think you’ll be called upon to hold any hands, Branson.’ Cartland’s voice was very dry. ‘How are we to regard ourselves? As kidnapees? As ransom for some lost cause you hold dear?’

‘The only lost cause I hold dear is standing before you.’

‘Then hostages to fortune?’

‘That’s nearer it. Hostages to a very large fortune, I trust.’ He looked again at the President. ‘I genuinely do apologize for any affront or inconvenience caused by me to your foreign guests.’

‘Inconvenience!’ The President’s shoulders sagged as he invoked his tragic Muse. ‘You don’t know what irreparable damage you have done this day, Branson.’

‘I wasn’t aware that I had done any yet. Or are you referring to their Highnesses here? I don’t see what damage I can have caused there. Or are you referring to your little trip to San Rafael today-I’m afraid we’ll have to postpone that for a bit-to inspect the site of what will be the biggest oil refinery in the world?’ He smiled and nodded towards the oil princes. ‘They really have you and Hansen over a barrel there, don’t they, Mr President – an oil barrel? First they rob you blind over oil sales, accumulate so much loot that they can’t find homes for all of it, conceive the bright idea of investing it in the land of the robbed, come up with the concept of building this refinery and petro-chemical complex on the West Coast and running it themselves – with your technical help, of course – on their own oil which would cost them nothing. The foreseeable profits are staggering, a large portion of which would be passed on to you in the form of vastly reduced oil prices. Bonanzas all round. I’m afraid international finance is beyond my scope – I prefer to make my money in a more direct fashion. If you think your deal is going to slip through because of the offence now being given to those Arabian gentlemen you must be an awful lot more naïve than a President of the United States has any right to be. Those are not gentlemen to be swayed by personal considerations. They have tungsten steel where their hearts should be and IBM computers for brains.’ He paused. ‘I’m not being very polite to your guests, am I?’

Neither the King nor Prince Achmed were quite so impassive now: their eyes, as they looked at Branson, were expressive of a distinct yearning.

Cartland said: ‘You seem to be in no great hurry to get on with whatever you intend to get on with.’

‘How right you are. The need for speed has now gone. Time is no longer of the essence except that the longer I spend here the more profitable it is going to be for me. That I shall explain later. In the meantime, the longer you remain here the more time it will give both you and your peoples both here and in the Gulf States to appreciate just what a pretty pickle you find yourselves in. And, believe me, you are in a pickle. Think about it.’

Branson walked to the rear of the coach and spoke to the blond young soldier who was manning the massive communication complex.

‘What’s your name?’

The soldier, who had heard all that had gone on and obviously didn’t like any of it, hesitated, then said grudgingly: ‘Boyann.’

Branson handed him a piece of paper. ‘Get this number, please. It’s just local.’

‘Get it yourself.’

‘I did say “please".’

‘Go to hell.’

Branson shrugged and turned. ‘Van Effen?’

‘Yes?’

‘Bring Chrysler here.’ He turned to Boyann. ‘Chrysler has forgotten a great deal more about telecommunications than you’ve learnt so far. You think I hadn’t anticipated meeting up with young heroes?’ He spoke to Van Effen. ‘And when you bring him take Boyann here out and have him thrown over the side of the bridge into the Golden Gate.’

‘Right away’

‘Stop!’ The President was shocked and showed it. ‘You would never dare.’

‘Give me sufficient provocation and I’ll have you thrown over the side too. I know it seems hard but you’ve got to find out some way, some time, that I mean what I say’

Muir stirred and spoke for the first time. He sounded tired. ‘I think I detect a note of sincerity in this fellow’s voice. He may, mark you, be a convincing bluffer. I, for one, wouldn’t care to be the person responsible for taking the chance.’

The President bent an inimical eye on the Under-Secretary but Muir seemed to have gone to sleep. Cartland said in a quiet voice: ‘Boyann, do what you are told.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Boyann seemed more than happy to have had the decision taken out of his hands. He took the paper from Branson who said: ‘You can put it through to the phone by that chair opposite the President’s?’ Boyann nodded. ‘And patch it in to the President’s?’ Boyann nodded again. Branson left and took his seat in the vacant armchair.

Boyann got through immediately: clearly, the call had been awaited.

‘Hendrix,’ the voice said.

‘Branson here.’

‘Yes. Branson. Peter Branson. God, I might have guessed!’ There was a silence then Hendrix said quietly: ‘I’ve always wanted to meet you, Branson.’

‘And so you shall, my dear fellow, and much sooner than you think. I’d like to speak to you later. Meantime, I wouldn’t be surprised if the President didn’t want to have a word with you.’ Branson stood up, not without difficulty, and offered both the telephone and seat to Morrison who in turn struggled to his feet and accepted the offer with alacrity.

The President ran true to the form of any President who might have been so unfortunate as to find himself in his position. He ran through the whole gamut of incredulity, outrage, disbelief and horror that not only the Chief Executive but, even more important, foreign potentates should find themselves in a situation so preposterous as to be, in his opinion, without parallel in history. He laid the blame, predictably, entirely at Hendrix’s door – security cover, as the President knew all too well, was arranged by Washington and the local police forces did precisely what they were told to do, but the President’s memory, logic and sense of justice had gone into a state of shock-and ended up by demanding that Hendrix’s duty was to clear up the whole damnable mess and that he should do something about it immediately.

Hendrix, who had a great deal longer time to consider the situation, remained admirably calm. He said: ‘What do you suggest I do about it, sir?’

The incoherent splutterings that followed were indication enough that constructive suggestions were at that moment some light years away from the President’s mind. Morrison took advantage of the momentary hiatus.

‘Bernard? John here.’ Morrison smiled without meaning to. ‘The voters aren’t going to like this, Bernard.’

‘All one hundred and fifty million of them?’

Again the same smile. ‘If we think nationally, yes.’

‘I’m afraid this is going to turn into a national problem, John. In fact, you know damn well it already is. And on the political side it’s too big for either of us.’

‘You cheer me up greatly, Bernard.’

‘I wish someone would cheer me. Do you think our friend would let me speak to the General?’

‘I’ll ask.’ He asked and Branson nodded amiably enough. The other occupants of the coach eyed one another with a mounting degree of suspicion and apprehension, both directed against Branson. The man was too utterly sure of himself. And, as matters stood at that moment, there seemed to be little reason why he shouldn’t be. He just didn’t hold all the aces in the pack – he held a pack full of aces.

Hendrix said: ‘General Cartland? Hendrix. The way I see it, sir, this is going to be as much a military operation as a police one. Much more so, if I’m any judge. I should call in the senior military officers on the coast?’

‘Higher than that.’

‘The Pentagon?’

‘At once.’

‘Local action?’

‘Damn all. Wait until the situation stabilizes itself – and we find out what this madman wants.’ Branson smiled politely but as usual the smile never touched his eyes. ‘According to what he says himself – if you can believe a word he says – time is not of the essence. I think he wants to talk to you.’

Branson took the phone from Cartland and eased himself comfortably into the armchair. ‘One or two questions and requests, Hendrix. I think I am in a position to expect answers and compliance with whatever I want. Wouldn’t you agree?’ ‘I’m listening.’

‘Has the news been broken yet?’

‘What the hell do you mean broken? Half of San Francisco can see you stuck out on that damned bridge.’

‘That’s no way to speak of my favourite bridge. Nationwide is what I mean.’

‘It’ll get around fast enough.’

‘See that it gets around now. The communications media, as those people term themselves nowadays, are going to be interested. I am prepared to allow, no, that’s wrong, I insist that you put a helicopter, no, two helicopters at the disposal of some of the hundreds of news cameramen who will wish to record this historic event. The Bay Area is thick with suitable machines, both military and civilian.’

There was a silence then Hendrix said: ‘What the devil do you want those for?’

‘Obvious, surely. Publicity. The maximum exposure. I want every person in America and indeed every person in the world who is within reach of a television set to see just what a predicament the President and his Arabian friends are in. And they are in a predicament, wouldn’t you say?’

Another silence. ‘This publicity, of course, you will use as a lever to get public opinion on your side, to help you obtain what you want, whatever that might be?’

‘What else?’

Hendrix said heavily: ‘You wouldn’t like me to send a coach-load of reporters on to the bridge, would you?’

Branson smiled into the telephone. ‘A coachload of reporters I wouldn’t mind but I don’t much fancy a coach-load of FBI men armed to the teeth and disguised as reporters. No, I think we’ll pass that one up. Besides, reporters we have, our own coach-load.’

‘What’s to prevent me from loading those helicopters up with troops, maybe paratroopers?’

Branson sighed. ‘Only your own common sense. We’ve got hostages, or had you forgotten? A bullet can reach the President far more quickly than a paratrooper ever could.’ Branson glanced at the President, whose expression indicated that he clearly didn’t care to be used as a bargaining counter.

‘You wouldn’t dare. You’d defeat your own ends. You’d have nothing left to blackmail us with.’

‘I’d still have a king and a prince. Try me and see. You’re whistling in the dark and you know it. Or do you want to go down in history as the man responsible for the deaths of a president, a king and a prince?’ Hendrix made no reply. It was clearly not a role he envisaged for himself. ‘However, it hasn’t escaped me that there might be some death-or-glory hotheads who would stop at nothing in taking blind gambles, so I’ve got my second request to make now. This area is crammed with military stations – the Presidio itself, Fort Baker, Treasure Island, Forts Funston, Miley and Mason, Fort Barry, Cronkite – you name them, they’re around and all within easy reach of here by road. I’d be very surprised if between them they can’t rustle up the two mobile self-propelled rapid-fire anti-aircraft guns which I want on the bridge within the hour. Plenty of ammunition, of course – and the army will test them out first. You know how some of that hardware gets afflicted with all kinds of jinxes.’

‘You’re quite mad.’

‘A divine sort of madness. Instructions now.’

‘I refuse.’

‘You refuse? General Cartland?’

Cartland heaved himself upright and walked heavily down the coach. He took the phone and said quietly: ‘Do what the madman asks. Don’t you recognize megalomania when you hear it?’

‘That was very unkind, General.’ Branson smiled and retrieved the phone. ‘You have the message, Hendrix?’

‘I have the message.’ Hendrix sounded as if he were being strangled.

‘My third request. Call up a couple of squads of army engineers. I want two sets of steel barriers built on the bridge, one under either tower. They are to be strong enough to stop a tank and high enough – barbed at the top, of course – to prevent anyone from climbing over. The north barrier is to be unbroken, the south with a hinged central section, wide enough to permit the passage of a jeep, and capable of being opened from the inside – our side – only. The barriers will be anchored to the sides of the bridge by bolting or welding and secured to the roadway by pneumatically driven spikes. But the army will know a great deal more about such things than I do. I shall supervise the operations personally.’

Hendrix seemed to be having some difficulty with his breathing. Finally he said: ‘Why?’

‘It’s those nasty fogs that come rolling in from the Pacific all the time. More often than not they cover the bridge – in fact I can see one coming in right now.’ Branson sounded almost apologetic. ‘It would be too easy to rush us under fog cover.’

‘And why the hinged section in the south barrier?’

‘I thought I told you. To permit the passage of a jeep. For such things as negotiating committees, a doctor if need be and the transport of the best food and drink in town.’

‘Jesus! You have your nerve, Branson.’

‘Nerve?’ Branson was hurt. ‘This humanitarian consideration of the well-being of my fellow man? You call that nerve? Kings and presidents are not accustomed to going hungry. Among other things you don’t want to go down in history as, Hendrix, includes I’m sure being the man responsible for starving kings and presidents to death. Think of the verdict of history.’

Hendrix was silent. He may or may not have been thinking about the verdict of history.

Branson went on: ‘And we must not forget the delicate sensibilities of royalty. Before the barriers are in place we’d like to have a couple of mobile latrine vans in position. Equipped, of course, to the very highest standards – and that does not include being loaded to the gunwales with FBI agents. You have all that, Hendrix?’

‘It’s been recorded.’

‘Then set the wheels in motion. Or must I call in General Cartland again?’

‘It will be done.’

‘Now?’

‘Now.’

Branson cradled the phone on his knee and looked at it wonderingly. ‘And he didn’t even tell me I couldn’t get off with it.’ He lifted the phone again. ‘Last request, Hendrix, but the most important one. The President is temporarily incapacitated. How can one talk to the leader of a leaderless nation?’

‘The Vice-President is already in Chicago. He’s on his way to O’Hare airfield now.’

‘Splendid. Splendid. Co-operation without even asking for it. But I’m afraid I’ll also have to ask for the co-operation of one or two other senior members of the government. I know it’s asking for a lot but I feel -’

‘Spare me your schoolboy humour, Branson.’ There was an edge to Hendrix’s voice now but it was a tired edge. ‘I suppose you have some people in mind?’

‘Just a couple, that’s all.’ Branson had a gift for sounding eminently reasonable when making the most unreasonable demands.

‘And if you get them and the Vice-President together here I suppose you’ll make all three of them hostages too.’

‘No. You’ve only got my word for it, of course, but no. You’re losing whatever grip you had, Hendrix. You don’t kidnap negotiators. If you did you’d have to negotiate with someone else and so on down the line until we came to someone like you.’ Branson waited for comment but Hendrix appeared to be beyond comment. ‘I want the Secretary of State.’

‘He’s on his way.’

‘A mind-reader, no less! From where?’

‘Los Angeles.’

‘How very convenient. How come he was there?’

‘An IMF meeting.’

‘IMF? Then that means -’

Branson replaced the receiver. ‘Well, well, well. Little Peter Branson vis-à-vis, the Secretary of the Treasury. What a tête-à-tête this should be. I thought the day would never come.’

‘Yes,’ Hendrix said wearily. ‘The Secretary of the Treasury was there. He’s flying up with him.’